Borgund Stave Church

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Norwegian. (December 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

| Borgund Stave Church | |

|---|---|

| Borgund stavkyrkje | |

View of the church | |

Borgund Stave Church Location of the church | |

| 61°02′50″N 7°48′44″E / 61.0472°N 07.8122°ECoordinates: 61°02′50″N 7°48′44″E / 61.0472°N 07.8122°E | |

| Location | Lærdal Municipality, Vestland |

| Country | Norway |

| Denomination | Church of Norway |

| Churchmanship | Evangelical Lutheran |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Former parish church |

| Founded | c. 1200 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Museum |

| Architectural type | Stave church |

| Completed | c. 1200 |

| Closed | 1868 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Wood |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Lærdal |

| Deanery | Sogn prosti |

| Diocese | Bjørgvin |

| Type | Church |

| Status | Automatically listed |

| ID | 83933 |

Borgund Stave Church (Norwegian: Borgund stavkyrkje) is a former parish church of the Church of Norway in Lærdal Municipality in Vestland county, Norway. The old stave church is located in the village of Borgund. It was the church for the Lærdal parish (which is part of the Sogn prosti (deanery) in the Diocese of Bjørgvin) until 1868 when it was closed and turned into a museum. The brown, wooden church was built in a stave church style around the year 1200. It is classified as a triple-nave stave church of the Sogn-type. No longer regularly used for church functions, it is now a museum run by the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments. It was replaced by the "new" Borgund Church in 1868.[1][2]

Construction[]

Borgund Stave Church was built sometime between 1180 and 1250 AD with later additions and restorations. Its walls are formed by vertical wooden boards, or staves, hence the name "stave church." The four corner posts are connected to one another by ground sills, resting on a stone foundation.[3] The intervening staves rise from the ground sills; each is tongued and grooved, to interlock with its neighbours and form a sturdy wall.[4]

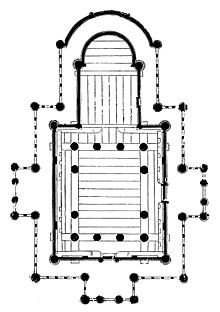

Borgund is built on a basilica plan, with reduced side aisles, and an added chancel and apse.[5] It has a raised central nave demarcated on four sides by an arcade. An ambulatory runs around this platform and into the chancel and apse, both added in the 14th century. An additional ambulatory, in the form of a porch, runs around the exterior of the building, sheltered under the overhanging shingled roof. The floor plan of this church resembles that of a central plan, double-shelled Greek cross with an apse attached to one end in place of the fourth arm. The entries to the church are in the three arms of the almost-cross.

Structurally, the building has been described as a "cube within a cube", each independent of the other. The inner "cube" is formed by continuous columns that rise from ground level to support the roof. The top of the arcade is formed by arched buttresses, knee jointed to the columns. Above the arcade, the columns are linked by cross-shaped, diagonal trusses, commonly dubbed "Saint Andrew's crosses"; these carry arched supports that offer the visual equivalent of a "second story". While not a functional gallery, this is reminiscent of contemporary second story galleries of large stone churches elsewhere in Europe. Smaller beams running between these upper supporting columns help clamp everything firmly together. The weight of the roof is thus supported by buttresses and columns, preventing downward and outward thrust on the stave walls.[6][7]

The roof beams are supported by steeply angled scissor trusses that form an X shape with a narrow top span and a broader bottom span, tied by a bottom truss to prevent collapse. Additional support is given by a truss that cuts across the X, below the crossing point but above the bottom truss. The roof is steeply pitched, boarded horizontally and clad with shingles. The original outer roof would have been weatherproofed with boards laid lengthwise, rather than shingles. In later years wooden shingles became more common.[8] Scissor beam roof construction is typical of most stave churches.[9]

Borgund has tiered, overhanging roofs, topped with a tower. On the gables of the roof, there are four carved dragon heads, swooping from the carved roof ridge crests,[10] recalling the carved dragon heads found on the prows of Norse ships. Similar gable heads also appear on small bronze house shaped reliquaries common in Norway in this period.[10] Borgund's current dragon heads possibly date from the 18th century,[10] however original dragon heads remaining on earlier structures, such as Lom Stave Church and nearby Urnes Stave Church, the oldest still extant stave church, also in the Sogn district, suggest that there probably would have been similar dragon heads there at one time.[11] Borgund is one of the only churches to still have preserved its ridge crests, carved with openwork vine and vegetal repeating designs.[10] The dragons on top of the church were often used as a form of drainage.

Most of the internal fittings have been removed. There is little in the building, apart from the row of benches that are installed along the wall inside the church in the ambulatory outside of the arcade and raised platform, a soapstone font, an altar (with 17th-century altarpiece), a 16th-century lectern, and a 16th-century cupboard for storing altar vessels. After the Reformation, when the church was converted for Protestant worship, pews, a pulpit and other standard church furnishings were included, however these have been removed since the building has come under the protection of the Fortidsminneforeningen (The Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments). There would have been more artwork in the building, most likely in the form of statues and crucifixes, as remain in a few other churches, but these are now lost.

Interior[]

The interior of the church is characterized by the twelve free-standing columns that support the nave's elevated central space. On the long side of the church there is a double interval between the second and third rods, but with a half rod resting on the lower bracing beam, the pliers, which runs in between. The double interval provides free access from the south portal to the church's central compartment, which would otherwise have been obstructed by the middle bar. The top of the poles is finished with grotesque, carved human and animal masks. The rods are secured with braces in the form of Andrew's crosses with a sun - shaped center and carved leaf shapes along the arms. The crosses also reappear as less ornate braces along the church walls. On the north and south sides of the nave, there are a total of eight windows that let in small amounts of light, and at the top of the nave's west gable is a window of more recent date - probably from pre-Reformation times, but a few years after the church was built. On the south wall of the nave, the inauguration crosses are still on the inside of the wall. The interior choir walls have engraved figures and runes that probably date from the Middle Ages.

The medieval interior of the stave church is almost untouched. However, the cross from the Middle Ages was removed after the Reformation. The original wooden floor and the benches that run along the walls of the nave are largely preserved, together with a medieval stone altar and a box-shaped baptismal font in soapstone. The pulpit in the church is from the period 1550–1570 and the altarpiece dates from 1654, while the frame around the tablet is dated to 1620.[12] The painting on the altarpiece shows the crucifixion in the middle, flanked by the Virgin Mary on the left and John the Baptist on the right. In the tympanum field, a white dove hovers on a blue background. Below the picture is an inscription with golden letters on a black background. In the church, a sacrament from the period 1550–1570 in the same style as the pulpit is also preserved. During the restoration of the church, carried out in the early 1870s with architect Christian Christie at the helm, benches and a gallery with seating on the second floor were removed. Several windows, including two large windows that were installed on the north and south sides in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as well as a ceiling over the chancel, were also removed. The goal was to return the church to pre-Reformation status. Parts of the inside of the church show signs of having been painted, which must have been done after the Reformation; this paint was also removed as part of the restoration.[13]

A local story tells that once upon a time there was a stuffed reindeer inside the church, shot during a mass. The antlers of the animal remained in the church when the animal was removed. Images from the 1990s show that the antlers hung on the lower, east-facing pliers in the church,[14] but how much of the story is true and where the antlers have taken the road in retrospect is not known. A travelogue from 1668 confirms the story, at least to some extent, as it states that the animal was shot during a sermon "when it marched like a wizard in front of the other animal carcasses".[15]

Bell[]

The church has a foundry with a bell from the Middle Ages, built in the middle of the 13th century, which is the only remaining free-standing bell tower in stavework in Norway today.[16] The foundry pool was probably originally open, but was recently covered. This is shown by the fact that the accounts mention that the bell tower was given a new door around the year 1700. This cladding was later removed, judging by photographs probably sometime between the 1920s and 1940s, and the foundry was left open for a long time. To preserve the interior, new walls were built on the outside of the stave in the 1990s.[13] Today, the church has relatively new bells, while one of the medieval bells is on display in the new Borgund church next door.

Dragon[]

According to Snorre Sturlason's works, Sogn is said to have been Christianized as early as 997, almost two hundred years before the church was founded, but several researchers believe that the population often dwelt on the Norse gods and kept to pagan tradition and faith well into Christian times. In the stave churches, therefore, a number of symbols with a pre-Christian background may have been used to facilitate the transition to Christianity, even though these symbols sometimes went in spite of the Christian faith.[17] At Borgund Stave Church, the four outer dragon heads are perhaps the clearest and most famous of all the symbols, apart from the crosses, and as on the Viking ships, they may have been used to keep away evil spirits that threatened the church building.[17] At the church, the dragon heads are placed on the ridge ridges on the nave and the roof rider's lower roof ledge. They can potentially be seen in the context of launchers in cathedrals such as Notre-Dame in Paris, as some researchers believe that these too are intended to deter evil spirits, but this is a controversial topic for which there is no concrete evidence. Among other things, Bugge places the dragon heads in contrast to, and not in connection with, such figures.[17] Some believe that pagan traditions originating from the dragon elements are an unreliable explanation; Anker refers, among other things, to several preserved reliquaries from both the Nordic countries and the continent that are designed as church buildings with dragon heads on the ridge ridges.[18]

On the lower side panel of the roof rider we find four circular cutouts. The carvings are very weather-beaten tarred and thus difficult to decipher, and there is disagreement about what they symbolize. Some believe they represent the four evangelists, probably rendered as an eagle, an ox, a lion and a human. Art historian Roar Hauglid claims, however, that the carvings show "dragons that extend their heads over to the neighboring field's dragon and bite into it", and points out the similarity to similar carvings at Høre Stave Church.[19]

The church's west portal, the nave's main entrance, is surrounded by a larger carving with dragons biting each other in the neck and tail. At the bottom of the half-columns that flank the front door, on the two inner corners of the carving, we find two dragon heads that spew powerful vine stalks that wind upwards and braid into the dragons above. The carving has strikingly similarities with the west portal of Ål Stave Church, which also has kites in a band braiding pattern, and it follows the usual composition in the Sogn-Valdres portals, a larger group of portals with very clear similarities. As Bugge writes, Christian authority may have come to terms with such pagan and "wild scenes" in the church building because the rift could be interpreted as a struggle between good and evil, in line with Christianity; in Christian medieval art, the dragon was often used as a symbol of the devil himself. Furthermore, Bugge points out that the carvings probably had a protective value, such as the dragon heads on the church roof.[17]

Runic inscriptions[]

Several runic inscriptions are found on the walls of the Church's west portal. One reads: Thor wrote these runes in the evening at the St. Olav's Mass. Another reads "Ave Maria".

Management[]

A new Borgund Church was built in 1868 right next to the old church, and the old church has not been in ordinary use since that year. Borgund Stave Church was bought by the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments in 1877. The first guidebook in English for the stave church was published in 1898.

Legacy[]

The church served as the inspiring example for the reconstruction of the Fantoft Stave Church in Fana, Bergen, in 1883 and for its rebuilding in 1997. The Gustav Adolf Stave Church in Hahnenklee, Germany, built in 1908, is modeled on the Borgund church. Three replicas exist in the United States, one at Chapel in the Hills, Rapid City, South Dakota,[20] another in Lyme, Connecticut,[21] and the third on Washington Island, Wisconsin.[22]

Gallery[]

The picture is taken from the National Library's picture collection

Picture taken from a book edited by J. C. C. Dahl, 1837

Picture taken in the periode 1880 - 1890

Stavkirken, Borgund, Martinus Rørbye, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, København, 1833

Borgund Stave Church in Lærdalen

Lion on arch decoration

Further read[]

In English[]

- Hauglid, Roar; trans. R. I. Christophersen (1970). Norwegian Stave Churches. Oslo: Dreyers Forlag.

- Hohler, Erla Bergendahl (1999). Norwegian Stave Church Sculpture. I. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press. ISBN 978-82-00-12748-2.

In Norwegian[]

- Aaraas, Margrethe Henden; Djupedal, Torkjell; Vengen, Sigurd og Førsund, Finn Borgen (2000). Hopperstad stavkyrkje – På kyrkjeferd i Sogn og Fjordane. Bind 2. Sogn og Fjordane fylkeskommune. s. 288–295, ISBN 82-91722-14-5.

- Anker, Peter (1997). Stavkirkene: Deres egenart og historie. Oslo: J.W. Cappelens forlag. ISBN 82-02-15978-4.

- Anker, Leif og Havran, Jiri (2005). De norske stavkirkene. Oslo: ARFO. ISBN 82-91399-27-1.

- Bakken, Kristin (red.); Anker, Leif; Nyhamar, Anne og Mehlum, Sjur (2016). Bevaring av stavkirkene: Håndverk og forskning. Oslo: Pax Forlag. ISBN 978-82-530-3875-9.

- Blindheim, Martin (2004). Gothic Painted Wooden Sculpture in Norway 1220–1350. Oslo: Messel forlag. ISBN 82-7631-072-9.

- Bugge, Gunnar (1981). Stavkirkene i Norge. Oslo. ISBN 82-09-01890-6.

- Bugge, Gunnar og Mezzanotte, Bernardino (1994). Stavkirker. Oslo: Grøndahl Dreyer. ISBN 82-504-2072-1.

- Christie, Håkon (1978). «Da Fortidsminnesmerkeforeningen reddet stavkirkene», Fortidsminneforeningens årbok 1978, s.43–62

- Hauglid, Roar (1973). Norske stavkirker: Dekor og utstyr. Oslo: Dreyer. ISBN 82-09-01079-4.

- Hauglid, Roar (1977). Norwegischer stabkirchen. Oslo: Dreyer. ISBN 82-09-00938-9.

- Lysne, Håkon (2018). Borgund kyrkje 150 År. Lærdal: Lysne forlag. ISBN 978-82-994525-2-6.

- Valebrokk, Eva og Thiis-Evensen, Thomas (1993). Levende fortid: De utrolige stavkirkene. Boksenteret. ISBN 82-7683-024-2.

- Storsletten, Ola (1995). Borgund stavkirke. Hagen Offset AS.

See also[]

- List of churches in Bjørgvin

- Runic inscription N 351

- Washington Island Stavkirke (Modeled after The Borgund Stave Church)

References[]

Note: Several sections of this article have been translated from its Norwegian version. For complete detailed references in Norwegian, see the original version at no:Borgund stavkirke.

- ^ "Borgund stavkyrkje". Kirkesøk: Kirkebyggdatabasen. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- ^ "Oversikt over Nåværende Kirker" (in Norwegian). KirkeKonsulenten.no. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- ^ "Borgund Stave Church". Fortidsminneforeningen (The Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments). Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 99.

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 32.

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 104.

- ^ Sheldon, Gwendolyn, “The Origin of the Norwegian Stave Church” at the Third Annual North American Interdisciplinary Conference on Medieval Icelandic Studies, Cornell University, May 2008, pp. 3–4

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 12.

- ^ Hauglid (1970)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hohler (1999), p. 69.

- ^ Hauglid (1970), p. 13

- ^ "Fortidsminneforeningen avdeling Sogn og Fjordane (Borgund stavkirke)". Retrieved 2006-02-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Borgund stavkyrkje".

- ^ Anker (1997), s. 71

- ^ Storsletten (1995), s. 20

- ^ "Borgund stavkyrkje" (en). Fortidsminneforeningen. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bugge (1994), s. 48

- ^ Anker og Havran (2005), s. 152

- ^ Hauglid (1973), s. 267

- ^ "History of the Chapel in the Hills". Chapel in the Hills. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ "Borgund Stave Church replica Lyme Connecticut". Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ Blei, Norbert. "Stavkirke". Washington Island. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Borgund stavkirke. |

- Borgund stave church in Stavkirke.org (in Norwegian)

- Borgund stave church in Fortidsminneforeningen

- Fortidsminneforeninga's stave church pages (in Norwegian) (there are also English and German pages)

- Replica in Rapid City

- Information about Borgund stave church (in English)

- Lærdal

- Churches in Vestland

- Wooden churches in Norway

- 12th-century churches in Norway

- 12th-century establishments in Norway

- Stave churches in Norway

- Buildings and structures owned by the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments