British occupation of the Faroe Islands

British occupation of the Faroe Islands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940–1945 | |||||||||

Flag | |||||||||

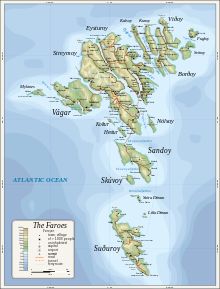

Location of the Faroe Islands | |||||||||

| Status | Military Occupation | ||||||||

| Government | Military Occupation | ||||||||

| Historical era | WW2 | ||||||||

• Occupation | 13 April 1940 | ||||||||

• Returned to Denmark | 13 May 1945 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Faroe Islands | ||||||||

The British occupation of the Faroe Islands in World War II, also known as Operation Valentine, was implemented immediately following the German invasion of Denmark and Norway. It was a small component of the roles of Nordic countries in World War II.[1]

In April 1940, the United Kingdom occupied the strategically important Faroe Islands to forestall a German invasion. British troops left shortly after the end of the war.

Occupation[]

| Operation Valentine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

British Second World War naval gun, Skansin fortress, Tórshavn | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Friendly invasion; no losses | |||||||

At the time of the occupation, the Faroe Islands had the status of an amt (county) of Denmark. Following the invasion and occupation of Denmark on 9 April 1940, British forces launched Operation Valentine to occupy the Faroe Islands. On 11 April, Winston Churchill – then First Lord of the Admiralty – announced to the House of Commons that the Faroe Islands would be occupied:

We are also at this moment occupying the Faroe Islands, which belong to Denmark and which are a strategic point of high importance, and whose people showed every disposition to receive us with warm regard. We shall shield the Faroe Islands from all the severities of war and establish ourselves there conveniently by sea and air until the moment comes when they will be handed back to Denmark liberated from the foul thraldom into which they have been plunged by German aggression.

An announcement was broadcast on BBC radio. An aircraft of the Royal Air Force (RAF) was seen over the Faroese capital Tórshavn on the same day. On 12 April, two destroyers of the Royal Navy arrived in Tórshavn harbour. Following a meeting with Carl Aage Hilbert (the Danish Prefect of the Islands) and Kristian Djurhuus (President of the Løgting, the Faroese Parliament), an emergency meeting of the Løgting was convened the same afternoon. Pro-independence members tried to declare the independence of the Faroe Islands from the Kingdom of Denmark but were outvoted. An official announcement was later made announcing the occupation and ordering a nighttime blackout in Tórshavn and neighbouring Argir, the censorship of post and telegraphy and the prohibition of the use of motor vehicles during the night without a permit.[2]

On 13 April, the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Suffolk arrived at Tórshavn. Colonel T. B. W. Sandall (the British military commander) and Frederick Mason (the new British Consul to the Faroe Islands) then met with the Danish Prefect. The Prefect responded with what Sandall took to be a formal protest, although Hilbert maintained that owing to the occupation of Denmark he was unable formally to represent the Danish government. He duly accepted the British terms on the basis that the UK would not seek to interfere with the internal affairs of the islands. A formal protest was made by the Løgting, albeit expressing the wish for friendly relations. 250 Royal Marines were disembarked, later to be replaced by other British troops. Cordial relations were maintained between the British forces and the Faroese authorities. In May, the Royal Marines were replaced by soldiers of the Lovat Scouts, a Scottish Regiment. In 1942, they were replaced by the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles). From 1944, the British garrison was considerably reduced. The author Eric Linklater was part of the British garrison and his 1956 novel The Dark of Summer was set in the Faroe Islands during the war years.

Events[]

On 20 June 1940, six Swedish Navy ships arrived in the Faroe Islands. Four, HSwMS Psilander, Puke, Romulus and Remus, were destroyers bought from Italy. The fifth, the passenger ship Patricia, was used to take the destroyer crew to Italy and bring civilian passengers back. The sixth, the tanker Castor, was converted to naval status to bunker the ships. The Royal Navy seized all the ships under armed threat and moved them to Orkney. Although Sweden was neutral and not at war, Britain feared Germany would seize the ships if they continued to Sweden. After political negotiations Sweden secured their return. The Royal Navy had stripped equipment and caused damage to the ships, for which Britain later paid compensation. The Swedish commander was criticised by other Swedish officers for conceding the ships without resistance.[citation needed]

Aftermath[]

A plaque has been erected by British veterans in Tórshavn Cathedral expressing thanks for the kindness shown to them by the Faroese people during their presence. Approximately 170 marriages took place between British soldiers and Faroese women; the British Consul, Frederick Mason (1913–2008) also married a local woman, Karen Rorholm.

The Faroe Islands suffered occasional attacks by Luftwaffe aircraft but an invasion was never attempted. Drifting sea mines proved to be a considerable problem and resulted in the loss of numerous fishing boats and their crews. The trawler Nýggjaberg was sunk on 28 March 1942 near Iceland; 21 Faroese seamen were killed in the worst loss of Faroese lives in the war. Faroese ships had to hoist the Faroese flag and paint FAROES / FØROYAR on the ships' sides, thus allowing the Royal Navy to identify them as "friendly".

To prevent inflation, Danish Krone banknotes in circulation on the islands were overstamped with a mark indicating their validity only in the Faroe Islands. The Faroese króna (technically the Danish Krone in the Faroe Islands) was fixed at 22.4 DKK to £1 Sterling. Emergency banknotes were issued and Faroese banknotes were later printed by Bradbury Wilkinson in England.[3]

During the occupation, the Løgting was given full legislative powers, albeit as an expedient given the occupation of Denmark. Although in the 1944 Icelandic constitutional referendum, Iceland became an independent republic, Churchill refused to countenance a change in the constitutional status of the Faroe Islands whilst Denmark was still occupied. Following the liberation of Denmark and the end of World War II in Europe, the occupation was terminated in May 1945 and the last British soldiers left in September. The experience of wartime self-government left a return to the pre-war status of an amt (county) unrealistic and unpopular. The 1946 Faroese independence referendum led to local autonomy within the Danish realm in 1948.

The largest tangible sign of the British presence is the runway of Vágar Airport. Other reminders include the naval guns at the fortress of Skansin in Tórshavn, which served as the British military headquarters. A continuing reminder is the Faroese love of fish and chips and British chocolate such as Dairy Milk (which is readily available in shops throughout the islands but not in Denmark).[citation needed] After the occupation, instances of multiple sclerosis increased in the Faroe Islands, something which American and German neuroepidemiologists such as John F. Kurtzke and Klaus Lauer attribute to the presence of occupying British soldiers who were recuperating from multiple sclerosis on the islands.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

In 1990, the Faroese government organised British Week, a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the friendly occupation. The celebration was attended by HMS Brilliant and a Royal Marines band. Sir Frederick Mason, the former wartime British consul to the Faroes, was also present, aged 76.[10]

Fatalities[]

More than 200 Faroese seamen lost their lives at sea during World War II, most due to the war. A monument in their memory stands in Tórshavn's municipal park. Several Faroese vessels were either bombed or sunk by German submarines or by drifting sea mines. Faroese fishing vessels harvested the sea near Iceland and around the Faroe Islands and transported their catch to the UK for sale.[11]

Airport[]

The only airfield on the Faroe Islands was built in 1942–43 on the island of Vágar by the Royal Engineers under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel William E. Law. The majority of the British personnel in the Faroes were stationed at Vágar, mostly working on the construction of the airfield. Abandoned after the war, it was reopened as the civilian Vágar Airport in 1963. Left-hand traffic was in force on the roads of the island of Vágar until the British troops left the Faroe Islands.

The Faroese flag[]

After Germany occupied Denmark, the British Admiralty no longer allowed Faroese vessels to fly the Danish flag. This was of considerable significance given the importance of the fishing fleet to the Faroese economy. Following some intensive discussions between the British occupation authorities, the Faroese authorities and the Danish Prefect, as well as discussions between the UK Foreign Office and the Danish Embassy in London, on 25 April 1940 the British authorities recognised the Faroese flag – Merkið – as the civil ensign of the Faroe Islands.[12]

Gallery[]

NASA photo of the islands

2005 Faroese stamp commemorating friendly relations between British soldiers and the Faroese

Grave of F/O H. J. G. Haeusler[a]

Remains of the British barracks at Vágar Airport

Faroe postage stamp showing the trawler Nýggjaberg, which was lost on 28 March 1942

British pillboxes or bunkers in Akraberg, the southernmost place in Suðuroy and the Faroe Islands

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ The gravestone of the Royal New Zealand Air Force pilot Flying Officer H. J. G. Haeusler, aged 24, near Vágar Airport.[13]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Miller 2003.

- ^ Niels Juel Arge, Stríðsárini VI (The Years of War VI) Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, at www.faroestamps.fo

- ^ Faroe Islands Paper Money – British Protectorate, Faerøerne, 1.10.1940 Emergency Issues.Archived 2006-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, article on Faroese currency during the British occupation

- ^ Kurtzke, JF; Hyllested, K (Jan 1979). "Multiple sclerosis in the Faroe Islands: I. Clinical and epidemiological features". Ann Neurol. 5 (1): 6–21. doi:10.1002/ana.410050104. PMID 371519. S2CID 8067353.

- ^ "multiple sclerosis". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ^ Lauer, K (Jun 1986). "Some comments on the occurrence of multiple sclerosis in the Faroe Islands". Journal of Neurology. 233 (3): 171–173. doi:10.1007/BF00314427. PMID 3522812. S2CID 22437259.

- ^ Brody, Jane E. "MS: A MEDICAL DETECTIVE STORY". Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- ^ Cooke, R. G. (2009). "MS in the Faroe Islands and the possible protective effect of early childhood exposure to the "MS agent"". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 82 (4): 230–233. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1990.tb01611.x. PMID 2270752. S2CID 9368103.

- ^ Kurtzke, JF; Heltberg, A (2001). "Multiple sclerosis in the Faroe Islands: an epitome". J Clin Epidemiol. 54 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00268-7. PMID 11165464.

- ^ Obituary of Sir Frederick Mason in The Times

- ^ Jacobsen, Óli (10 November 2010). "Sosialurin". Faroes.

- ^ History of the Faroese flag Archived 1999-02-24 at the Wayback Machine, Flags of the World

- ^ BBC.co.uk - WW2 People's War: Sole Survivor Archived 2012-07-24 at archive.today (about the surviving crew member of the plane crash), 30 December 2005

References[]

- Miller, James (2003). The North Atlantic Front: Orkney, Shetland, Faroe, and Iceland at War. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84341-011-9.

- Conflicts in 1940

- Faroe Islands in World War II

- Allied occupation of Europe

- Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

- Battles and conflicts without fatalities

- World War II occupied territories

- British military occupations

- World War II operations of the Western European Theatre

- Invasions by the United Kingdom

- World War II invasions

- Denmark–United Kingdom relations

- Sweden–United Kingdom relations

- Maritime incidents in April 1940

- Maritime incidents in June 1940

- Battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- 1940 in the Faroe Islands

- Scotland in World War II

- Denmark–Scotland relations