Calaveras Big Trees State Park

| Calaveras Big Trees State Park | |

|---|---|

Giant sequoias in Calaveras South Grove | |

| |

| Location | Calaveras and Tuolumne counties, California, United States |

| Nearest city | Arnold, California |

| Coordinates | 38°16′22″N 120°17′26″W / 38.27278°N 120.29056°WCoordinates: 38°16′22″N 120°17′26″W / 38.27278°N 120.29056°W |

| Area | 6,498 acres (26.30 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,560–4,920 ft (1,390–1,500 m) |

| Established | 1931 |

| Governing body | California Department of Parks and Recreation |

Calaveras Big Trees State Park is a state park of California, United States, preserving two groves of giant sequoia trees. It is located 4 miles (6.4 km) northeast of Arnold, California in the middle elevations of the Sierra Nevada. It has been a major tourist attraction since 1852, when the existence of the trees was first widely reported, and is considered the longest continuously operated tourist facility in California.

History[]

Early History[]

The giant sequoia was well known to Native American tribes living in its area. Native American names for the species include Wawona, toos-pung-ish and hea-mi-within, the latter two in the language of the Tule River Tribe.

The first reference to the giant sequoias of Calaveras Big Trees by Europeans is in 1833, in the diary of the explorer J. K. Leonard; the reference does not mention any specific locality, but his route would have taken him through the Calaveras Grove.[1] This discovery was not publicized. The next European to see the trees was John M. Wooster, who carved his initials in the bark of the 'Hercules' tree in the Calaveras Grove in 1850; again, this received no publicity. Much more publicity was given to the "discovery" by Augustus T. Dowd of the North Grove in 1852, and this is commonly cited as the discovery of both the grove and the species as a whole.[1]

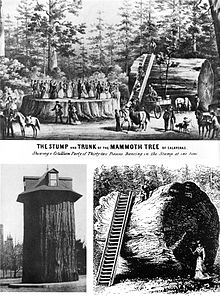

The "" was noted by Augustus T. Dowd in 1852 and felled in 1853, leaving a giant stump and a section of trunk showing the holes made by the augers used to fell it.[2] It measured 25 ft (7.6 m) in diameter at its base and was determined by ring count to be 1,244 years old when felled. A section of the trunk was toured with little fanfare while the stump was later turned into a dance floor. John Muir wrote an essay titled "The Vandals Then Danced Upon the Stump!" to criticize the felling of the tree.[3]

In 1854, a second tree named the "Mother of the Forest" was skinned alive, of its bark in 1854, to be reassembled at exhibitions. This mortally wounded the tree, since outer layer of protective bark was take away, tree lost its resistance to fire. If you look closely there are still horizontal saw marks in the wood to remove it bark. The tree didn't survive long after, having shed its entire canopy by 1861.[4] In 1908, with the tree unprotected by its fire resistant bark, a fire swept through the area and burned away much of what was left of the tree.[5] Today, only a fire-blackened snag remains of the Mother of the Forest.

In early 1880s,[6][7] a tunnel was cut through the compartments by a private land owner at the request of James Sperry, founder of the Murphys Hotel, so that tourists could pass through it.[8][9][10][11][12] The tree was chosen in part because of the large forest fire scar. The Pioneer Cabin Tree, as it was soon called, emulated the tunnel carved into Yosemite's Wawona Tree, and was intended to compete with it for tourists.[13][14][15]

Calls for preservation[]

Despite or due to the 1850s exhibitions, the destruction of the big trees was met with public outcry.[16] In 1864, on introducing the bill that would become the Yosemite Grant, senator John Conness opined that even after people had seen the physical evidence of the and the Mother of the Forest, they still didn’t believe the trees were genuine, and that the areas they were from should be protected instead.[17] However, this did not guarantee any legal protection for the trees of Calaveras Grove.

Establishing Calaveras Big Trees State Park[]

By the turn of the century the land was owned by several lumber companies, with plans to cut the remaining trees down, as sequoia and giant sequoia with their thick trunks were seen as great sources of lumber at the time.[18] This again caused a chorus of public outcry by locals and conservationists, and the area continued to be treated as a tourist attraction. The Yosemite protection was gradually extended to most sequoias,[19] and Calaveras Grove was joined to California State Parks in 1931.[20][21]

Parcels of land that would later become the state park and nearby national park were optioned by lumberman in January 1900, with the intention of logging. A protracted battle to preserve the trees was launched by Laura Lyon White and the . Despite legislation in 1900 and 1909 authorizing the federal government to purchase the property, Whiteside refused to sell the land at the offered price, preferring its higher valuation as parkland. It was not until 1931 that Whiteside's family began to divest the property, beginning with the North Grove.[22]

The area was declared a state park in 1931 and now encompasses 6,498 acres (2,630 ha) in Calaveras and Tuolumne counties.[23][2]

Over the years other parcels of mixed conifer forests, including the much larger South Calaveras Grove of Giant Sequoias (purchased in 1954 for US $2.8 million, equivalent to US $27 million in 2020 dollars), have been added to the park to bring the total area to over 6,400 acres (2,600 ha). The North Grove contains about 100 mature giant sequoias; the South Grove, about 1,000.[2] According to Naturalist John Muir the forest protected by the park is: "A flowering glade in the very heart of the woods, forming a fine center for the student, and a delicious resting place for the weary."[24]

Attractions[]

The North Grove includes several noteworthy giant sequoias:

- : the stump of what was once the largest tree of the park.

- Mother of the Forest: a fire-blackened snag is all that remains of the second largest tree of the park.

- Pioneer Cabin Tree: a giant sequoia tree that collapsed during a storm on January 8, 2017; it was one of only two living giant sequoia tunnel trees still standing (the other being the California Tunnel Tree of Mariposa Grove).

- Empire State: the largest tree of the North Grove, which measures 30 ft (9.1 m) at ground level and 23 ft (7.0 m) at 6 ft (1.8 m) above ground.[25]

The South Grove also included several noteworthy giant sequoias:

- : the largest living tree of the Calaveras groves measuring 250 feet (76 m) tall and more than 25 feet (7.6 m) in diameter 6 feet (1.8 m) above ground.[26] It is the 37th largest giant sequoia in the world, and could be considered either the 36th or 35th largest depending on how badly Ishi Giant and Black Mountain Beauty have atrophied following devastating wildfires in 2015 and 2017, respectively.

- Palace Hotel Tree: the second largest living tree of the Calaveras groves; features a large deep burn scar at its base that one can walk into. This tree has nails burned into its inner trunk by past travelers.

Other attractions of Calaveras Big Trees include the Stanislaus River, Beaver Creek, the Lava Bluff Trail, and Bradley Trail.[2]

Activities[]

The park houses two main campgrounds with a total of 129 campsites, six picnic areas and hundreds of miles of established trails.[2]

Other activities include cross-country skiing, evening ranger talks, numerous interpretive programs, environmental educational programs, junior ranger programs, hiking, mountain biking, bird watching and summer school activities for school children. Dogs are welcome in the park on leash in developed areas like picnic sites, campgrounds, roads and fire roads (dirt). Dogs are not allowed on the designated trails, nor in the woods in general.[2]

See also[]

- Calaveras Big Tree National Forest

- Chandelier Tree - another tunnel tree, but a coast redwood not a giant sequoia

- List of giant sequoia groves

- List of California state parks

References[]

Notes[]

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Farquhar, Francis P. (1925). "Discovery of the sierra Nevada". California Historical Society Quarterly. 4 (1): 3–58. doi:10.2307/25177743. hdl:2027/mdp.39015049981668. JSTOR 25177743., Yosemite.ca.us

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Calaveras Big Trees State Park". Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ McKinney, John (2002-10-13). "An autumn walk through Calaveras County's majestic groves". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ "The Mammoth Trees of California" (PDF), Hutchings’ California Magazine (33), p. 392, March 1859

- ^ Hawken 2008, p. 51.

- ^ "Trip to the Big Trees". Sacramento Daily Union. 18 (15). 8 September 1883. p. 2.

The "Pioneers’ Cabin" had a large burnt cavity, which this year has been so enlarged by workmen, that a stage could easily pass through it with enough of the tree left on each side to support it in health.

- ^ California State Parks (2008). "Hanging On By A Branch: The Pioneer Cabin Tree".

- ^ "The Latest: Famed giant sequoia topples in California storms". Associated Press. January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Carol Kramer; Calaveras Big Trees Association (September 6, 2010). Calaveras Big Trees. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-4396-2522-4.

- ^ Bourn, Jennifer (September 28, 2016). "The Calaveras Big Trees North Grove Trail". Inspiredimperfection.com. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "The Pioneer's Cabin and Pluto's Chimney – Big Tree Grove, Calaveras County" (Albumen Photograph). Library of Congress. 1866. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "Iconic Pioneer Cabin tree falls during strong Northern California storm" (Video). CBS News. January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Hongo, Hudson (January 9, 2017). "After More Than 100 Years, California's Iconic Tunnel Tree Is No More". Gizmodo. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Mazza, Ed (January 9, 2017). "GREEN: Pioneer Cabin Tree, Iconic Giant Sequoia With 'Tunnel', Falls In Storm". The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

The tree was “barely alive” due to the hole punched through it in the 1880s.

- ^ Summers, Jordan (May 15, 2012). 60 Hikes Within 60 Miles: Sacramento: Including Auburn, Folsom, and Davis. Birmingham, Alabama: Menasha Ridge Press. p. 120. ISBN 0897326040.

- ^ Hickman, Leo (27 June 2013). "How a giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement 160 years ago". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "The Congressional Globe". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875. May 18, 1864. p. 2301.

From the Calaveras grove some sections of a fallen tree were cut during and pending the great World’s Fair that was held in London some years since. One joint of the tree was sectionized and transported to that country in sections, and then set up there. The English who saw it declared it to be a Yankee invention, made from beginning to end; that it was an utter untruth that such trees grew in the country; that it could not be

- ^ Dollar, George (July 1897), "Timber Titans", The Strand Magazine, 14 (79)

- ^ Hartesveldt, Richard J. (1975). The Giant Sequoia of the Sierra Nevada. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. p. 3.

- ^ Kramer, Carol (2010). Calaveras Big Trees. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439625224.

- ^ Isne, John (2013). Our National Park Policy: A Critical History. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 9781135990503.

- ^ Binkley, Cameron (2005). "A Cult of Beauty: The Public Life and Civic Work of Laura Lyon White". California History. 82 (2): 48–49. JSTOR 25161804.

- ^ "California State Park System Statistical Report: Fiscal Year 2009/10" (PDF). California State Parks: 18. Retrieved October 29, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ St. John, Paige; Hamilton, Matt (January 8, 2017). "An iconic tunnel tree in a California state park is no more after huge storm". Los Angeles Times. Truckee, California. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ North Grove Guidebook, Calaveras Big Trees State Park

- ^ "How Big are Big Trees?". California State Parks. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calaveras Big Trees State Park. |

- Calaveras Big Trees State Park

- Calaveras Big Trees Association

- "The Pioneer's Cabin and Pluto's Chimney - Big Tree Grove, Calaveras County - B&W Film Copy Neg" (Albumen Photograph). Library of Congress. 1866. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- State parks of California

- Campgrounds in California

- Forests of California

- Giant sequoia groves

- Parks in Calaveras County, California

- Protected areas established in 1931

- Protected areas of the Sierra Nevada (U.S.)

- 1931 establishments in California

- History of Calaveras County, California