California State University

This article relies too much on references to primary sources. (October 2019) |

| |

| Motto | Vox Veritas Vita (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | "Voice Truth Life" (Speak the truth as a way of life.) |

| Type | Public university system |

| Established | 1857 |

| Endowment | $1.82 billion, as of June 30, 2019.[1] |

| Budget | $5.77 billion (2017)[2] |

| Chancellor | Joseph I. Castro |

| Students | 485,550 (Fall 2020)[3] |

| Undergraduates | 432,264 (Fall 2019)[3] |

| Postgraduates | 53,286 (Fall 2019)[3] |

| Location | Long Beach , California , United States |

| Campus | 23 campuses |

| Colors | Red & White |

| Affiliations | State of California |

| Website | www |

The California State University (Cal State or CSU) is a public university system in California. With 23 campuses and eight off-campus centers enrolling 485,550 students with 55,909 faculty and staff,[4] CSU is the largest four-year public university system in the United States.[5] It is one of three public higher education systems in the state, with the other two being the University of California system and the California Community Colleges. The CSU System is incorporated as The Trustees of the California State University. The California State University system headquarters are in Long Beach, California.[6]

The California State University system was created in 1960 under the California Master Plan for Higher Education, and it is a direct descendant of the California State Normal Schools chartered in 1857.[7] With nearly 100,000 graduates annually, the CSU is the country's greatest producer of bachelor's degrees.[7] The university system collectively sustains more than 150,000 jobs within the state, and its related expenditures reach more than $17 billion annually.[7]

In the 2011–12 academic year, CSU awarded 52 percent of newly issued California teaching credentials, 47 percent of the state's engineering degrees, 28 percent of the state's information technology bachelor's degrees, and it had more graduates in business (50 percent), agriculture (72 percent), communication studies, health (53 percent), education, and public administration (52 percent) than all other universities and colleges in California combined.[8] Altogether, about half of the bachelor's degrees, one-third of the master's degrees, and nearly two percent of the doctoral degrees awarded annually in California are from the CSU.[9]

Furthermore, the CSU system is one of the top U.S. producers of graduates who move on to earn their Ph.D. degrees in a related field.[10] The CSU has a total of 17 AACSB accredited graduate business schools which is over twice as many as any other collegiate system.[11] Since 1961, nearly three million alumni have received their bachelor's, master's, or doctoral degrees from the CSU system. CSU offers more than 1,800 degree programs in some 240 subject areas.[12] In fall of 2015, 9,282 (or 39 percent) of CSU's 24,405 faculty were tenured or on the tenure track.[13]

History[]

The State Normal Schools[]

Today's California State University system is the direct descendant of the Minns Evening Normal School, a normal school in San Francisco that educated the city's future teachers in association with the high school system. The school was taken over by the state in 1862 and moved to San Jose and renamed the California State Normal School; it eventually evolved into San Jose State University.[14] A southern branch of the California State Normal School was created in Los Angeles in 1882.[15]

In 1887, the California State Legislature dropped the word "California" from the name of the San Jose and Los Angeles schools, renaming them "State Normal Schools." Later Chico (1887), San Diego (1897), and other schools became part of the State Normal School system.[16] However, these did not form a system in the modern sense, in that each normal school had its own board of trustees and all were governed independently from one another. In 1919, the State Normal School at Los Angeles became the Southern Branch of the University of California; in 1927, it became the University of California at Los Angeles (the "at" was later replaced with a comma in 1958).[17]

The State Teachers Colleges[]

In May 1921, the legislature enacted a comprehensive reform package for the state's educational system, which went into effect that July.[18] The State Normal Schools were renamed State Teachers Colleges, their boards of trustees were dissolved, and they were brought under the supervision of the Division of Normal and Special Schools of the new California Department of Education located at the state capital in Sacramento.[18] This meant that they were to be managed from Sacramento by the deputy director of the division, who in turn was subordinate to the State Superintendent of Public Instruction (the ex officio director of the Department of Education) and the State Board of Education. By this time it was already commonplace to refer to most of the campuses with their city names plus the word "state" (e.g., "San Jose State," "San Diego State," "San Francisco State").

The resulting administrative situation from 1921 to 1960 was quite complicated. On the one hand, the Department of Education's actual supervision of the presidents of the State Teachers Colleges was minimal, which translated into substantial autonomy when it came to day-to-day operations.[19] According to Clark Kerr, J. Paul Leonard, the president of San Francisco State from 1945 to 1957, once boasted that "he had the best college presidency in the United States—no organized faculty, no organized student body, no organized alumni association, and...no board of trustees."[20] On the other hand, the State Teachers Colleges were treated under state law as ordinary state agencies, which meant their budgets were subject to the same stifling bureaucratic financial controls as all other state agencies (except the University of California).[19] At least one president would depart his state college because of his express frustration over that issue: Leonard himself.[19]

During the 1920s and 1930s, the State Teachers Colleges started to transition from normal schools (that is, vocational schools narrowly focused on training elementary school teachers in how to impart basic literacy to young children) into teachers colleges (that is, providing a full liberal arts education) whose graduates would be fully qualified to teach all K–12 grades.[21] A leading proponent of this idea was Charles McLane, the first president of Fresno State, who was one of the earliest persons to argue that K–12 teachers must have a broad liberal arts education.[21] Having already founded Fresno Junior College in 1907 (now Fresno City College), McLane arranged for Fresno State to co-locate with the junior college and to synchronize schedules so teachers-in-training could take liberal arts courses at the junior college.[21]

The State Colleges[]

In 1932, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching was asked by the state legislature and governor to perform a study of California higher education.[21] The Foundation's 1933 report sharply criticized the State Teachers Colleges for their intrusion upon UC's liberal arts prerogative and recommended their transfer to the Regents of the University of California (who would be expected to put them back in their proper place).[21] This recommendation spectacularly backfired when the faculties and administrations of the State Teachers Colleges rallied to protect their independence from the Regents.[21] In 1935, the State Teachers Colleges were formally upgraded by the state legislature to State Colleges and were expressly authorized to offer a full four-year liberal arts curriculum, culminating in bachelor's degrees, but they remained under the Department of Education.[21]

During World War II, a group of local Santa Barbara leaders and business promoters (with the acquiescence of college administrators) were able to convince the state legislature and governor to transfer Santa Barbara State College to the University of California in 1944.[22] After losing a second campus to UC, the state colleges' supporters arranged for the California state constitution to be amended in 1946 to prevent it from happening again.[22]

The period after World War II brought a great expansion in the number of state colleges. Additional state colleges were established in Los Angeles, Sacramento, and Long Beach from 1947 to 1949, and then seven more state colleges were authorized to be established between 1957 and 1960. Six more state colleges were founded after the enactment of the Donahoe Higher Education Act of 1960, bringing the total number to 23.

The California State Colleges[]

During the 1950s, the state colleges' peculiar mix of fiscal centralization and operational decentralization began to look rather incongruous in comparison to the highly centralized University of California (then on the brink of its own decentralization project) and the highly decentralized local school districts around the state which operated K–12 schools and junior colleges—all of which enjoyed much more autonomy from the rest of the state government than the state colleges.

The state legislature was limited to merely suggesting locations to the UC Board of Regents for the planned UC campus on the Central Coast.[23] In contrast, because the state colleges lacked autonomy, they became vulnerable to pork barrel politics in the state legislature. In 1959 alone, state legislators introduced separate bills to individually create nineteen state colleges. Two years earlier, one bill that had actually passed had resulted in the creation of a new state college in Turlock, a town better known for its turkeys than its aspirations towards higher education, and which made no sense except that the chair of the Senate Committee on Education happened to be from Turlock.[24]

In April 1960, the California Master Plan for Higher Education and the resulting Donahoe Higher Education Act granted similar autonomy to the state colleges. The Donahoe Act merged all the state colleges into the State College System of California, severed them from the Department of Education (and also the State Board of Education and the State Superintendent of Public Instruction), and authorized the appointment of a systemwide board of trustees and a systemwide chancellor. The board was initially known as the "Trustees of the State College System of California"; the word "board" was not part of the official name. In March 1961, the state legislature renamed the system to the California State Colleges (CSC) and the board became the "Trustees of the California State Colleges."[25]

As enacted, the Donahoe Act provides that UC "shall be the primary state-supported academic agency for research" and "has the sole authority in public higher education to award the doctoral degree in all fields of learning".[26] In contrast, CSU may only award the doctoral degree as part of a joint program with UC or "independent institutions of higher education" and is authorized to conduct research "in support of" its mission, which is to provide "undergraduate and graduate instruction through the master’s degree."[26] This language reflects the intent of UC President Kerr and his allies to bring order to "a state of anarchy"—in particular, the state colleges' repeated attempts (whenever they thought UC was not looking) to quietly blossom into full-fledged research universities, as was occurring elsewhere with other state colleges like Michigan State.[24]

Kerr explained in his memoirs: "The state did not need a higher education system where every component was intent on being another Harvard or Berkeley or Stanford."[27] As he saw it, the problem with such mission creep was that state resources would be spread too thin across too many universities, all would be too busy chasing the "holy grail of elite research status" (in that state college faculty members would inevitably demand reduced teaching loads to make time for research) for any of them to fulfill the state colleges' traditional role of training teachers, and then "some new colleges would have to be founded" to take up that role.[27] At the time, California already had too many research universities; it had only 9 percent of the American population but 15 percent of the research universities (12 out of 80).[28] The language about joint programs and authorizing the state colleges to conduct some research was offered by Kerr at the last minute on December 18, 1959, as a "sweetener" to secure the consent of a then-wavering Glenn Dumke, the state colleges' representative on the Master Plan survey team.[29] (Dumke had succeeded Leonard in 1957 as president of San Francisco State College.)

Most state college presidents and approximately 95 percent of state college faculty members (at the nine campuses where polls were held) strongly disagreed with the Master Plan's express endorsement of UC's primary role with respect to research and the doctorate, but they were still subordinate to the State Board of Education.[30] In January 1960, Louis Heilbron was elected as the new chair of the State Board of Education.[31] A Berkeley-trained attorney, Heilbron had already revealed his loyalty to his alma mater by joking that UC's ownership of the doctorate ought to be protected from "unreasonable search and seizure."[31] He worked with Kerr to get the Master Plan's recommendations enacted in the form of the Donahoe Act, which was signed into state law on April 27, 1960.[30]

Heilbron went on to serve as the first chairman of the Trustees of the California State Colleges (1960-1963), where he had to "rein in some of the more powerful campus presidents," improve the smaller and weaker campuses, and get all campuses accustomed to being managed for the first time as a system.[32] Heilbron set the "central theme" of his chairmanship by saying that "we must cultivate our own garden" (an allusion to Candide) and stop trying to covet someone else's.[33] Under Heilbron, the board also attempted to improve the quality of state college campus architecture, "in the hope that campuses no longer would resemble state prisons."[32]

Buell G. Gallagher was selected by the board as the first chancellor of the California State Colleges (1961-1962), but resigned after only nine unhappy months to return to his previous job as president of the City College of New York.[34] Dumke succeeded him as the second chancellor of the California State Colleges (1962-1982). As chancellor, Dumke faithfully adhered to the system's role as prescribed by the Master Plan,[30] despite continuing resistance and resentment from state college dissidents who thought he had been "out-negotiated" and bitterly criticized the Master Plan as a "thieves' bargain".[28] Looking back, Kerr thought the state colleges had failed to appreciate the vast breadth of opportunities reserved to them by the Master Plan, as distinguished from UC's relatively narrow focus on basic research and the doctorate.[28] In any event, "Heilbron and Dumke got the new state college system off to an excellent start."[33]

The California State University and Colleges[]

In 1972, the system became The California State University and Colleges, and the board was renamed the "Trustees of the California State University and Colleges". The board also became known in the alternative as the "Board of Trustees," similar to how the Regents of the University of California are also known in the alternative as the Board of Regents.

On May 23, 1972, fourteen of the nineteen CSU campuses were renamed to "California State University," followed by a comma and then their geographic designation.[35] The five campuses exempted from renaming were the five newest state colleges created during the 1960s.[35] The new names were very unpopular at certain campuses, and in 1974, all CSU campuses were given the option to revert to an older name: e.g., San Jose State, San Diego State, San Francisco State, etc.

The California State University[]

In 1982, the CSU system dropped the word "colleges" from its name.

Today the campuses of the CSU system include comprehensive universities and polytechnic universities along with the only maritime academy in the western United States—one that receives aid from the U.S. Maritime Administration.

In May 2020, it was announced that all 23 institutions within the CSU system would host majority-online courses in the Fall 2020 semester as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of the pandemic on education[36][37][38]

Governance[]

The governance structure of the California State University is largely determined by state law. The California State University is ultimately administered by the 25 member (24 voting, one non-voting) Board of Trustees of the California State University. The Trustees appoint the Chancellor of the California State University, who is the chief executive officer of the system, and the Presidents of each campus, who are the chief executive officers of their respective campuses.

The Academic Senate of the California State University, made up of elected representatives of the faculty from each campus, recommends academic policy to the Board of Trustees through the Chancellor.

Board of Trustees[]

The California State University is administered by the 25 member Board of Trustees (BOT). Regulations of the BOT are codified in Title 5 of the California Code of Regulations (CCR). The BOT is composed of:[39][40][41]

- The Governor of California (president ex officio)

- Sixteen members who are appointed by the Governor of California with the consent of the Senate

- Two students from the California State University appointed by the Governor

- One tenured faculty member appointed by the Governor selected from a list of names submitted by the Academic Senate

- One representative of the alumni associations of the state university selected for a two-year term by the alumni council of the California State University

- Four ex officio members aside from the Governor:

- Lieutenant Governor

- Speaker of the Assembly

- State Superintendent of Public Instruction

- The CSU Chancellor

Current members[]

Ex officio trustees:

- Gavin Newsom, Governor of California

- Eleni Kounalakis, Lieutenant Governor of California

- Anthony Rendon, Speaker of the Assembly

- Tony Thurmond, State Superintendent of Public Instruction

- Joseph I. Castro, CSU Chancellor

Appointed trustees: Silas Abrego, Jane W. Carney, Adam Day (Chair), Rebecca D. Eisen, Douglas Faigin, Debra S. Farar, Jean P. Firstenberg, Wenda Fong, Lillian Kimbell (Vice-chair), Jack McGrory, Thelma Melendez de Santa Ana, Hugo M. Moralas, John Nilon, J. Lawrence Norton, Romey Sabalius, Lateefah Simon, Christopher Steinhauser, Peter J. Taylor.[42]

Student Trustees (also appointed): Emily F. Hinton (voting) and Juan Garcia (non-voting).

Chancellor[]

The position of the Chancellor is declared by statute and is defined by resolutions of the BOT. The delegation of authority from the BOT to the Chancellor was historically governed by a BOT resolution titled "Statement of General Principles in the Delegation of Authority and Responsibility" of August 4, 1961. It is now controlled by the Standing Orders of the Board of Trustees of the California State University.[43] Under the Standing Orders, the Chancellor is the chief executive officer of the CSU, and all Presidents report directly to the Chancellor.[43]

Chancellors[]

- Buell Gallagher (1961–1962)

- Glenn S. Dumke (1962–1982)

- W. Ann Reynolds (1982–1990)

- Ellis E. McCune [Acting] (1990–1991)

- Barry Munitz (1991–1998)

- Charles B. Reed (1998–2012)

- Timothy P. White (2012–2020)[44]

- Joseph I. Castro (2021)[45]

Student government[]

All 23 campuses have mandatory student body organizations with mandatory fees, all with the "Associated Students" moniker, and are all members of the California State Student Association (CSSA). California Education Code § 89300 allows for the creation of student body organizations at any state university for the purpose of providing essential activities closely related to, but not normally included as a part of, the regular instructional program.[46] A vote approved by two-thirds of all students causes the Trustees to fix a membership fee required of all regular, limited, and special session students attending the university such that all fee increases must be approved by the Trustees and a referendum approved by a majority of voters.[46] Mandatory fee elections are called by the president of the university,[47] and the membership fees are fixed by the Chancellor.[48] All fees are collected by the university at the time of registration except where a student loan or grant from a recognized training program or student aid program has been delayed and there is reasonable proof that the funds will be forthcoming.[49] The mandates that the legislative body of a student body organization conduct its business in public meetings.[50]

Student body organization funds obtained from mandatory fees may be expended for:[51]

- Programs of cultural and educational enrichment and community service.

- Recreational and social activities.

- Support of student unions.

- Scholarships, stipends, and grants-in-aid for only currently admitted students.

- Tutorial programs.

- Athletic programs, both intramural and intercollegiate.

- Student publications.

- Assistance to recognized student organizations.

- Student travel insurance.

- Administration of student fee program.

- Student government-scholarship stipends, grants-in-aid, and reimbursements to student officers for service to student government. Before such scholarship stipends, grants-in-aid, and reimbursements are established by a student body association, the principle of establishing such payments shall be approved by a student referendum.

- Student employment to provide payment for services in connection with the general administration of student fee.

- Augmentation of counseling services, including draft information, to be performed by the campus. Such counseling may also include counseling on legal matters to the extent of helping the student to determine whether he should retain legal counsel, and of referring him to legal counsel through a bar association, legal aid foundation or similar body.

- Transportation services.

- Child day care centers for children of students and employees of the campus.

- Augmentation of campus health services. Additional programs may be added by appropriate amendment to this section by the Board.

Impact[]

The CSU confers over 70,000 degrees each year, awarding 46% of the state's bachelor's degrees and 32% of the state's master's degrees.[52] The entire 23 campus system sustains nearly 150,000 jobs statewide,[52] generating nearly $1 billion in tax revenue. Total CSU related-expenditures equate to nearly $17 billion,[52]

The CSU produces 62% of the bachelor's degrees awarded in agriculture, 54% in business, 44% in health and medicine, 64% in hospitality and tourism, 45% in engineering, and 44% of those in media, culture and design.[52][clarification needed] The CSU is the state's largest source of educators, with more than half of the state's newly credentialed teachers coming from the CSU, expanding the state's rank of teachers by nearly 12,500 per year.[52]

Over the last 10 years, the CSU has significantly enhanced programs towards the underserved. 56% of bachelor's degrees granted to Latinos in the state are from the CSU, while 60% of bachelor's awarded to Filipinos were from the CSU.[52] In the Fall of 2008, 42% of incoming students were from California Community Colleges.[52]

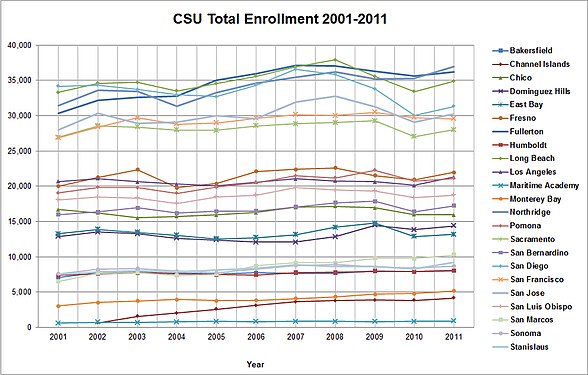

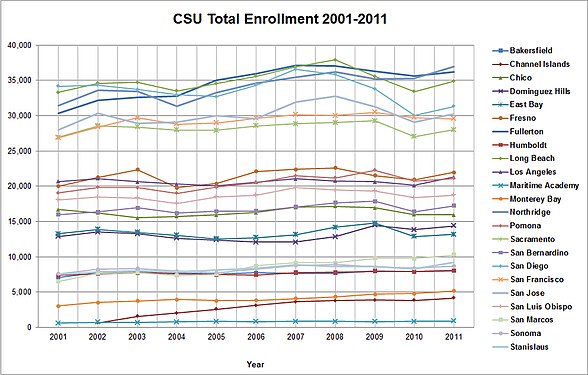

Enrollment[]

- CSU Enrollment Infographics

Total Enrollment ('01-'11)

Historical Enrollment ('70-'11)

Gender Composition (2011)

| Campuses (2020)[54] | Undergraduate (2020)[55] | Graduate (2020)[55] | Doctorate (2020)[55] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native American or American Indians | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Hispanic and Latino Americans (Includes Chicanos, Other Latino and White Hispanics) |

45% | 46% | 35% | 25% |

| Non-Hispanic White Americans | 22% | 21% | 29% | 36% |

| Non-Hispanic Asian American | 15% | 16% | 13% | 16% |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 4% | 4% | 4% | 7% |

| Non-Hispanic Multiracial Americans | 4% | 4% | 3% | 5% |

| Unknown | 4% | 3% | 5% | 5% |

| International students | 5% | 5% | 9% | 5% |

Compensation and hiring[]

During the recession years (December 2007 – June 2009), the CSU lost 1/3 of its revenue – roughly $1 billion – and 4,000 employees. With the state's reinvestment in higher education, the CSU is restoring its employee ranks and currently employs a record number of instructional faculty. Between 2010 and 2015, the number of CSU faculty increased by 3,500, but the number of tenure track faculty declined by 150, leaving the CSU system with its lowest percentage of tenure track faculty (39%) in the schools' history.[13][56] In the two years (2013–14, 2014–15) through the state's reinvestment, the CSU has directed $129.6 million to enhance employee compensation. Another $65.5 million in slated in the 2015–16 operating budget for employee compensation. However, according to the California Faculty Association (CFA) report, "Race to the Bottom: CSU's 10-Year Failure to Fund Its Core Mission", written in 2015, "Over the past decade— in good times and bad, whether state funding was up or down, when tuition was raised and when it wasn’t— CSU expenditures on faculty salaries have remained essentially flat... When compared to other university systems around the country, and to every education segment in California, the CSU stands out for its unparalleled failure to improve faculty salaries or even to protect them from the ravages of inflation."[57]

| 2018 Total Employees by Occupational Group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Faculty | 27,134 | 51.4% |

| Professional and Technical | 14,886 | 28.2% |

| Management | 1,730 | 3.3% |

| Office and Administrative Support | 4,643 | 8.8% |

| Service Occupations | 2,650 | 5.0% |

| Construction, Maintenance, and Transportation | 1,765 | 3.3% |

| Total | 52,808 | 100% |

(For data definitions and additional statistics, please see the CSU Employee Profile at www.calstate.edu/hr/employee-profile/.)

Campuses[]

The CSU is composed of the following 23 campuses listed here by order of the year founded:

| Campus | Founded | Total acreage |

Enrollment (Fall 2019)[3] |

Operations estimate (2012–2013) (millions)[7] |

Endowment (Fiscal year 2017-2018) (millions)[58] |

Athletic affiliation |

Athletic Nickname (Conference) |

2021 U.S. News Rank (West)[59][60] |

Washington Monthly Rank (Master's, 2020)[61][62] |

Forbes Rank (National, 2019)[63] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Jose | 1857 | 154 | 33,282 | $239.16 | $150.1 | NCAA Div. I (FBS) |

Spartans (MW) |

22 | 61 | 295 |

| Chico | 1887 | 119 | 17,019 | $145.76 | $64.7 | NCAA Div. II | Wildcats (CCAA) |

26 | 15 | 335 |

| San Diego | 1897 | 283 | 35,081 | $281.24 | $293.0 | NCAA Div. I (FBS) |

Aztecs (MW) |

143 (Nat. Univ.)* |

121 (Nat. Univ.)* |

181 |

| San Francisco | 1899 | 141 | 28,880 | $240.64 | $90.8 | NCAA Div. II | Gators (CCAA) |

29 | 96 | 426 |

| San Luis Obispo | 1901 | 9,678 | 21,242 | $211.80 | $220.5 | NCAA Div. I (FCS) |

Mustangs (Big West) |

3 | 26 | 115 |

| Fresno | 1911 | 1,399 | 24,139 | $183.53 | $161.6 | NCAA Div. I (FBS) |

Bulldogs (MW) |

196 (Nat. Univ.)* |

26 (Nat. Univ.)* |

417 |

| Humboldt | 1913 | 144 | 6,983 | $92.87 | $30.1 | NCAA Div. II | Lumberjacks (CCAA) |

37 | 45 | 623 |

| Maritime | 1929 | 87 | 911 | $29.11 | $8.8 | NAIA | Keelhaulers (Cal Pac) |

2 (Reg. Coll.)^ |

7 (Reg. Coll.)^ |

309 |

| Pomona | 1938 | 1,438 | 27,914 | $178.82 | $99.7 | NCAA Div. II | Broncos (CCAA) |

10 | 57 | 273 |

| Los Angeles | 1947 | 175 | 26,361 | $177.77 | $40.1 | NCAA Div. II | Golden Eagles (CCAA) |

26 | 10 | 499 |

| Sacramento | 1947 | 300 | 31,156 | $209.53 | $48.0 | NCAA Div. I (FCS) |

Hornets (Big Sky) |

43 | 13 | 469 |

| Long Beach | 1949 | 330 | 38,074 | $277.02 | $77.2 | NCAA Div. I (non-football) |

The Beach[a] (Big West) |

14 | 18 | 272 |

| Fullerton | 1957 | 236 | 39,868 | $268.77 | $65.0 | NCAA Div. I (non-football) |

Titans (Big West) |

16 | 29 | 300 |

| Stanislaus | 1957 | 220 | 10,614 | $77.43 | $16.4 | NCAA Div. II | Warriors (CCAA) |

29 | 9 | 434 |

| East Bay | 1957 | 341 | 14,705 | $135.46 | $17.1 | NCAA Div. II | Pioneers (CCAA) |

80 | 153 | 492 |

| Northridge | 1958 | 353 | 38,391 | $278.31 | $110.7 | NCAA Div. I (non-football) |

Matadors (Big West) |

40 | 11 | 474 |

| Dominguez Hills | 1960 | 346 | 17,027 | $93.67 | $10.4 | NCAA Div. II | Toros (CCAA) |

58 | 21 | NR |

| Sonoma | 1960 | 269 | 8,649 | $81.50 | $49.1 | NCAA Div. II | Seawolves (CCAA) |

33 | 164 | 457 |

| San Bernardino | 1965 | 409 | 20,311 | $146.27 | $37.7 | NCAA Div. II | Coyotes (CCAA) |

40 | 3 | 500 |

| Bakersfield | 1965 | 375 | 11,199 | $74.81 | $25.7 | NCAA Div. I (non-football) |

Roadrunners (Big West) |

52 | 19 | NR |

| San Marcos | 1989 | 304 | 14,519 | $89.54 | $24.9 | NCAA Div. II | Cougars (CCAA) |

60 | 51 | NR |

| Monterey Bay | 1994 | 1,365 | 7,123 | $66.62 | $23.9 | NCAA Div. II | Otters (CCAA) |

25 | 22 | NR |

| Channel Islands | 2002 | 1,193 | 7,093 | $63.67 | $15.7 | None | Dolphins (N/A) |

43 | 31 | NR |

- ^ Long Beach State fully rebranded its athletic program as "The Beach" in 2020–21, after transitioning from the former nickname of 49ers. The baseball team is also known as "Dirtbags".

* U.S. News & World Report ranks San Diego State and Fresno State in the National Universities category as they offer several Ph.D programs. The other universities in the California State University system are ranked in the Regional Universities (West) category as they offer few or no Ph.D programs.

^ Cal Maritime only awards undergraduate degrees and therefore is ranked separately from the other campuses of the California State University. It is ranked in the "Regional Colleges" category.[64]

Gallery[]

San Jose

Chico

San Diego

San Francisco

San Luis Obispo

Fresno

Humboldt

Pomona

Los Angeles

Sacramento

Long Beach

Fullerton

Stanislaus

East Bay

Northridge

Dominguez Hills

Sonoma

San Bernardino

Bakersfield

San Marcos

Monterey Bay

Channel Islands

Off campus branches[]

A handful of universities have off campus branches that make education accessible in a large state. Unlike the typical university extension courses, they are degree-granting and students have the same status as other California State University students. The newest campus, the California State University, Channel Islands, was formerly an off campus branch of CSU Northridge. Riverside County and Contra Costa County, which have three million residents between them, have lobbied for their off campus branches to be free-standing California State University campuses. The total enrollment for all off campus branches of the CSU system in Fall 2005 was 9,163 students, the equivalent of 2.2 percent of the systemwide enrollment. The following are schools and their respective off campus branches:

- California State University, Bakersfield

- Antelope Valley (in Lancaster, California)

- California State University, Chico

- Redding (affiliated with Shasta College)

- California State University, Fullerton

- Irvine

- Garden Grove

- California State University, East Bay

- Concord

- Oakland (Professional & Conference Center)

- California State University, Fresno

- Visalia

- California State University, Los Angeles

- Downtown Los Angeles

- California State University, Monterey Bay

- Salinas (Professional & Conference Center)

- California State University, San Bernardino

- Palm Desert

- California State University, San Marcos

- Temecula/Murrieta

- San Diego State University

- Imperial Valley (in Brawley, California and Calexico, California)

- SDSU-Georgia (in Tbilisi in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia)

- San Francisco State University

- Cañada College (in Redwood City, California)

- Downtown Campus (in San Francisco, California)

- California State University, Stanislaus

- Stockton, California[65]

- Sonoma State University

- Rohnert Park, California

Laboratories and observatories[]

Research facilities owned and operated by units of the CSU:

- Desert Studies Center

- Research consortium and field site managed by California State University, Fullerton[66]

- Moss Landing Marine Laboratories

- Independent degree-granting campus managed by San Jose State University

- Oceanographic laboratory located in the Monterey Bay area[67]

- Murillo Family Observatory

- Newest research observatory in the San Bernardino Metropolitan Area and the CSU system. It is located in and managed by California State University, San Bernardino.[68]

- Southern California Marine Institute

- Oceanographic laboratory in the Los Angeles Basin[69]

- Mount Laguna Observatory

- Astronomical observatory part of the Astronomy Department of San Diego State University[70]

- T.S. Golden Bear

- The training ship of the California Maritime Academy[71]

- Telonicher Marine Laboratory at Humboldt State University in Trinidad, CA[72]

- Marine research laboratory on the North California coast

- Home of the research vessel RV Coral Sea

Former campuses[]

Former campuses of the CSU system:

- Los Angeles State Normal School (State Normal School at Los Angeles), founded 1882, became the University of California at Los Angeles in 1919.

- Santa Barbara State College, founded 1909, became the University of California at Santa Barbara in 1944.[73]

Differences between the CSU and UC systems[]

Both California public university systems are publicly funded higher education institutions. Despite having far fewer students, the largest UC campus, UCLA, as a result of its research emphasis and medical center, has a budget ($7.5 billion as of 2019) roughly equal to that of the entire CSU system ($7.2 billion as of 2019). According to a 2002 study, faculty at the CSU spend about 30 hours a week teaching and advising students and about 10 hours a week on research/creative activities, while a 1984 study reports faculty at the UC spend about 26 hours a week teaching and advising students and about 23 hours a week on research/creative activities.[74][75] CSU's Chancellor, Dr. Charles B. Reed, pointed out in his Pullias Lecture at the University of Southern California that California was big enough to afford two world-class systems of public higher education, one that supports research (UC) and one that supports teaching (CSU). However, student per capita spending is lower at CSU, and that, together with the lack of a research mission or independent doctoral programs under the California Master Plan, has led some in American higher education to develop the perception that the CSU system is less prestigious than the UC system.[76][77][78][79][80] Kevin Starr, the seventh State Librarian of California, stated that the "University of California drew from the top ten percent of the state's high school graduates" while "the CSU system was expected to draw its students from the top 33 percent of each graduating high school class."[81] However, per the California Master Plan, the UC draws from the top 12.5 percent of California's public high school graduates.[82]

According to the California Master Plan for Higher Education (1960), both university systems may confer bachelors or master's degrees as well as professional certifications, however only the University of California has the authority to issue Ph.D degrees (Doctor of Philosophy) and professional degrees in the fields of law, medicine, veterinary, and dentistry. As a result of recent legislation (SB 724 and AB 2382), the California State University may now offer the Ed.D (also known as the Doctor of Education or "education doctorate degree") and DPT (Doctor of Physical Therapy) degrees to its graduate students. Additionally, the California State University (CSU) offers Ph.D degrees and some professional doctorates (for instance, audiology, Au.D) as a "joint degree" in combination with other institutions of higher education, including "joint degrees" with the University of California (UC) and accredited private universities. This is why, for instance, San Diego State can qualify as a "Doctoral University: High Research Activity"[83] by offering some 22 doctoral degrees.

There are 23 CSU campuses and 10 UC campuses representing approximately 437,000 and 237,000[84] students respectively. The cost of CSU tuition is approximately half that of UC.[citation needed] Thus, the CSU system has been referred to by former California State University authorities as "The People's University."[85]

CSU and UC use the terms "president" and "chancellor" internally in opposite ways: At CSU, the campuses are headed by presidents who report to a systemwide chancellor;[43] but at UC, they are headed by chancellors who report to a systemwide president.[86]

CSU has traditionally been more accommodating to older students than UC, by offering more degree programs in the evenings and, more recently, online.[87][citation needed] In addition, CSU schools, especially in more urban areas, have traditionally catered to commuters, enrolling most of their students from the surrounding area. This has changed as CSU schools increase enrollment and some of the more prestigious urban campuses attract a wider demographic.[88]

The majority of CSU campuses operate on the semester system while UC campuses operate on the quarter system (with the exception of UC Berkeley, UC Merced, the UCLA medical school, and all UC law schools). As of Fall 2014, the CSU began converting its six remaining quarter campuses to the semester calendar.[89] Cal State LA and Cal State Bakersfield converted in Fall 2016,[90] while Cal State East Bay and Cal Poly Pomona transitioned to semesters in Fall 2018.[91][92] Cal State San Bernardino is planning to make the conversion in Fall 2020,[93] while Cal Poly San Luis Obispo has not announced a date for conversion to semesters.

Admission standards[]

Historically the requirements for admission to the CSU have been less stringent than the UC system. However, both systems require completion of the A-G requirements in high school as part of admission. The CSU attempts to accept applicants from the top one-third of California high school graduates. In contrast, the UC attempts to accept the top one-eighth. In an effort to maintain a 60/40 ratio of upper division students to lower division students and to encourage students to attend a California community college first, both university systems give priority to California community college transfer students.

However, the following 17 CSU campuses use higher standards than the basic admission standards due to the number of qualified students who apply which makes admissions at these schools more competitive:[94]

- Chico

- Fresno

- Fullerton

- Humboldt (freshmen)

- Long Beach

- Los Angeles

- Monterey Bay (freshmen)

- Northridge

- Pomona

- Sacramento

- San Bernardino

- San Diego

- San Francisco

- San Jose

- San Luis Obispo

- San Marcos

- Sonoma

Furthermore, seven California State University campuses are fully impacted for both freshmen and transfers, meaning in addition to admission into the school, admission into all majors is also impacted for the academic 2020-2021 program. The seven campuses that are fully impacted are Los Angeles, Fresno, Fullerton, Long Beach, San Diego, San Jose, and San Luis Obispo.

Campus naming conventions[]

The UC system follows a consistent style in the naming of campuses, using the words "University of California" followed by the name of its declared home city, with a comma as the separator. Most CSU campuses follow a similar pattern, though several are named only for their home city or county, such as San Francisco State University, San Jose State University, San Diego State University, or Sonoma State University.

Some of the colleges follow neither pattern. California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo and California State Polytechnic University, Pomona use the word "polytechnic" in both their full names (but in different word orders) per California Education Code section 89000.[95] and section 89005.5[96] CSU's editorial style guide refers to the same formal names while they also refer to the abbreviated forms "Cal Poly San Luis Obispo" and "Cal Poly Pomona" respectively, but not the name "Cal Poly" by itself.[97] Cal Poly San Luis Obispo unilaterally claims the "Cal Poly" name per its own marketing brand guides[98] and, since the 1980s, the CSU Chancellor's Office has taken numerous small and medium-sized businesses to court on Cal Poly San Luis Obispo's behalf for not having a licensing agreement to sell merchandise with the words "Cal Poly".[99][100]

In addition, the California Maritime Academy (Cal Maritime) is the only campus whose official name does not refer to its location in California.[101] Both Channel Islands and San Marcos campuses' official names do not include a comma, unlike the typical style of the CSU naming convention, and instead follow California State University San Marcos, or Channel Islands.[102] Some critics, including Donald Gerth (former President of Sacramento State), have claimed that the weak California State University identity has contributed to the CSU's perceived lack of prestige when compared to the University of California.[103]

Fall 2018 enrolled freshmen profile[]

| Campus | Applicants[104] | Admits[104] | Admit Rate |

Non-Resident[105] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakersfield | 12,935 | 10,440 | 80.7% | 4.2% |

| Channel Islands | 11,330 | 8,876 | 78.3% | 2.4% |

| Chico | 23,964 | 15,639 | 65.3% | 3.2% |

| Dominguez Hills | 20,235 | 12,939 | 63.9% | 4.5% |

| East Bay | 16,131 | 11,549 | 71.6% | 8.3% |

| Fresno | 18,476 | 10,630 | 57.5% | 6.0% |

| Fullerton | 51,415 | 22,317 | 43.4% | 7.6% |

| Humboldt | 10,957 | 8,414 | 76.8% | 1.5% |

| Long Beach | 69,610 | 21,725 | 31.2% | 6.4% |

| Los Angeles | 39,854 | 16,548 | 41.5% | 7.6% |

| Maritime | 1,117 | 743 | 66.5% | 0.4% |

| Monterey Bay | 12,423 | 7,270 | 58.5% | 5.9% |

| Northridge | 34,856 | 17,647 | 50.6% | 8.0% |

| Pomona | 36,662 | 20,220 | 55.2% | 6.6% |

| Sacramento | 27,108 | 17,312 | 63.9% | 3.9% |

| San Bernardino | 16,045 | 8,798 | 54.8% | 7.4% |

| San Diego | 69,399 | 23,998 | 34.6% | 7.8% |

| San Francisco | 35,606 | 25,550 | 71.8% | 7.8% |

| San Jose | 36,243 | 19,811 | 54.7% | 12.3% |

| San Luis Obispo | 54,663 | 16,491 | 30.2% | 2.3% |

| San Marcos | 17,649 | 10,311 | 58.4% | 4.8% |

| Sonoma | 14,478 | 12,980 | 89.7% | 2.8% |

| Stanislaus | 7,674 | 6,586 | 85.8% | 3.5% |

| System-wide | 637,350 | 318,991 | 50.0% | 6.5% |

Impacted campuses[]

An impacted campus or major is one which has more CSU-qualified students than capacity permits. As of 2012, 16 out of the 23 campuses are impacted including Chico, Fresno, Fullerton, Humboldt, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Northridge, Pomona, San Bernardino, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Sonoma, San Marcos, and San Luis Obispo. Some programs at other campuses are similarly impacted. All undergraduate programs, pre-programs, and undeclared/undecided programs are impacted for the following campuses: as the academia year 2021-22 for Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, Fresno State, CSU Fullerton, Cal State LA, CSU Long Beach, San Diego State University, and San José State. Despite this, CSU undergraduate admissions are quantitatively based and generally do not include items such as personal statements, SAT Subject Test scores, letters of recommendation, or portfolios. In addition, there is geographic preference given to those residing within the commuting areas of the colleges.[106]

Special admissions process for the California Maritime Academy[]

The Maritime Academy uses a different admissions process from other CSU schools. Because of the nature of its programs, the Maritime Academy requires all applicants to pass a standard physical examination prior to enrollment.[107]

Research and academics[]

AAU, AASCU and APLU[]

The University of California and most of its campuses are members of the Association of American Universities (AAU) and the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (APLU).

The California State University (CSU) and most of its campuses are members of APLU and the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU).

ABET[]

ABET (Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, Inc.) is the recognized U.S. accreditor of college and university programs in applied and natural science, computing, engineering, and engineering technology. The California State University has 18 colleges with ABET-accredited programs.[108]

- Cal Poly Pomona, Cal Poly Pomona College of Engineering

- Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, College of Engineering

- CSU Maritime Academy, School of Engineering

- CSU Bakersfield, School of Natural Sciences, Mathematics, and Engineering

- CSU Chico, College of Engineering, Computer Science, & Construction Management

- CSU Dominguez Hills, College of Natural & Behavioral Sciences

- CSU East Bay, College of Science

- CSU Fresno, Lyles College of Engineering

- CSU Fullerton, College of Engineering & Computer Science

- CSU Long Beach, College of Engineering

- CSU Los Angeles, College of Engineering, Computer Science, and Technology

- CSU Northridge, College of Engineering & Computer Science

- CSU Sacramento, College of Engineering & Computer Science

- CSU San Bernardino, College of Natural Sciences

- Humboldt State University, College of Natural Resources & Sciences

- San Diego State University, College of Engineering

- San Francisco State University, College Science & Engineering

- CSU San José State University, Charles W. Davidson College of Engineering

CENIC[]

The CSU is a founding and charter member of CENIC, the Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California, the nonprofit organization which provides extremely high-performance Internet-based networking to California's K–20 research and education community.

Statewide university programs[]

Agricultural Research Initiative[]

A comprehensive applied agricultural and environmental research program joining the CSU's four colleges of agriculture (at San Luis Obispo, Pomona, Chico and Fresno) and the state's agriculture and natural resources industries and allied business communities.[109]

- Cal Poly Pomona

- Cal Poly San Luis Obispo

- Chico State

- Fresno State

Biotechnology[]

The California State University Program for Education and Research in Biotechnology (CSUPERB) mission is to develop a professional biotechnology workforce. CSUPERB provides grant funding, organizes an annual symposium, sponsors industry-responsive curriculum, and serves as a liaison for the CSU with government, philanthropic, educational, and biotechnology industry partners. The program involves students and faculty from Life, Physical, Computer and Clinical Science, Engineering, Agriculture, Math and Business departments at all 23 CSU campuses.[110]

Coastal Research and Management[]

The CSU Council on Ocean Affairs, Science & Technology (CSU COAST) affinity group is the umbrella organization for marine, coastal, and coastal watershed-related activities. A highly effective CSU affinity group with active faculty and administration members across each of the system's 23 campuses, CSU COAST functions primarily as a coordinating force to stimulate new research, teaching, and policy tools via administrative support, robust networking opportunities, and by providing small incubator/accelerator funding to students and faculty.

Graduation Initiative 2025

The Graduation Initiative 2025 is a plan to increase graduation rates, eliminate equity gaps in degree completion and meet California's workforce needs.[111] The initiative organizes an annual symposium with keynote speakers such as, California Governor Gavin Newsom.[112] The initiative focuses mainly on enhancing guidance and academic planning for first generation and transfer students. The initiative has resulted in a six percentage point increase in the four-year graduation rate of first-time freshman over three years, from 19.2 percent in 2015 to 25.4 percent in 2018 and an increase in the six-year graduation by four percentage points, from 57 percent in 2015 to 61.1 percent in 2018.[113]

Hospitality Management[]

The Hospitality Management Education Initiative (HMEI) was formed in 2008 to address the shortage of hospitality leaders in California. HMEI is a collaboration between the 14 CSU campuses that have hospitality-related degrees and industry executives.[114] CSU awarded 95% of hospitality bachelor's degrees in the state in 2011.[115]

Nursing[]

Headquartered and administered at the Dominguez Hills campus, the CSU Statewide Nursing Program offers registered nurses courses available throughout California that lead to Bachelors, Masters of Science, and a Doctoral degree in Nursing (awarded by the closest participating CSU campus).[116] The campuses that award a Doctorate in Nursing Practice (DNP) are:

- Fresno

- Fullerton

- Long Beach

- Los Angeles

- San Jose

Online Education and Concurrent Enrollment[]

Beginning in 2013, the CSU made a radical change in the way it delivered online education. The university approved more than 30 courses for system-wide consumption, meaning any student attending one of the 23 campuses will be able to enroll in an online course offered at another campus, concurrently. The new online education delivery method is part of $17 million additional funding from the state to improve online education, and ultimately improve graduation rates and access to "bottleneck courses" across the 23 campuses. Courses offered include biology, business finance, chemistry, and microeconomics.[117][118]

Pre-doctoral Program[]

California Pre-Doctoral Program is designed to increase the pool of potential faculty by supporting the doctoral aspirations of California State University students who have experienced economic and educational disadvantages.[119]

The Chancellor's Doctoral Incentive Program provides financial and other assistance to individuals pursuing doctoral degrees. The program seeks to provide loans to doctoral students who are interested in applying and competing for California State University instructional faculty positions after completion of the doctoral degree.[120]

Professional Science Master's Degrees[]

The CSU intends to expand its post-graduate education focus to establish and encourage Professional Science master's degree (PSM) programs using the Sloan model.[121][122]

See also[]

- California State Employees Association

- California State University Emeritus and Retired Faculty Association

- California State University Police Department

- Colleges and universities

- List of colleges and universities in California

References[]

- ^ "Donor Support 2018–19 - Overview". California State University Office of the Chancellor.

- ^ "2017-18 Support Budget" (pdf). The California State University. p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Workbook: Enrollment Dashboard". The California State University Data Center: Institutional Research and Analyses. Archived from the original on August 25, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "The CSU 2018 Factbook". The California State University. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ "CSU Facts 2017" (PDF). The California State University.

- ^ Home Page. California State University. Retrieved on December 6, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "CSU Media Center" (PDF). Calstate.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ Systemwide Information | Measuring the Value of a CSU Education | CSU. Calstate.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ "Working for California: The Impact of the California State University System" (PDF). Office of the Chancellor. May 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ The Colleges Where PhD's Get Their Start. The College Solution. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ "Accredited Institutions". AACSB. AACSB. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ Graduation Facts | 100,000 Graduates Strong Archived June 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Blogs.calstate.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Faculty and Staff Demographics | 2015 Facts About the CSU | PA | CSU". Calstate.edu. Retrieved 2015-10-21.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 5–9. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 11–26. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 26–30. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. p. xxi. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 176–177. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 23–24, 33–35. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Stadtman, Verne A. (1970). The University of California, 1868–1968. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 412–413.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 174. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Cal. Stats., 1961 reg. sess., ch. 12, pp. 540-571.

- ^ Jump up to: a b California Education Code Section 66010.4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 178. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 182. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nelson, Valerie J. (January 1, 2007). "Louis H. Heilbron, 99; headed first Cal State trustees board". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. pp. 120–129. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gerth, Donald R. (2010). The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Berkeley Public Policy Press. p. 548. ISBN 9780877724353.

- ^ "California State University campuses to remain closed through fall semester, online instruction to continue". ABC7 Los Angeles. 2020-05-13. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ Theresa Waldrop; Jon Passantino; Sarah Moon. "Some of California's main universities not likely to return to campus this fall". CNN. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ Hubler, Shawn (2020-05-12). "Fearing a Second Wave, Cal State Will Keep Classes Online in the Fall". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ California Education Code, §66602

- ^ "The CSU Board of Trustees". The California State University. 2008-01-18. Archived from the original on 2008-02-01. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "The California State University Board of Trustees Almanac / Supplement, 1981-1988" (PDF). 1989. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 30, 2017. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ "Meet the Board of Trustees". www2.calstate.edu. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Standing Orders of the Board of Trustees of the California State University (as revised through March 21, 2018).

- ^ Lovekin, Kris (October 4, 2012). "Timothy White to Leave UC Riverside to be Chancellor of 23-Campus California State University System". UCR Today. University of California, Riverside. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ "Fresno State president, Valley native Joseph Castro selected as next CSU chancellor". KGET 17. 2020-09-23. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b California Education Code § 89300 Archived 2009-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 5 CCR § 41401

- ^ 5 CCR § 41408

- ^ "CA Codes (edc:89300-89304)". 2009-04-30. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ "CA Codes (edc:89305-89307.4)". 2009-04-29. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ 5 CCR § 42659

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Working for California: The Impact of the California State University System" (PDF). Calstate.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "CSU - AS - Statistical Reports". calstate.edu.

- ^ "CSU; Enrollment by Ethnic Group - Fall 2020". Calstate.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "CSU | AS | Enrollment by Ethnic Group - Fall 2020" (PDF). Calstate.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-15.

- ^ "CSU Employee Profile" (PDF). Calstate.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "race-to-the-bottom - California Faculty Association". Calfac.org. Retrieved 2015-10-21.

- ^ As of June 30, 2018. "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2017 to FY 2018" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute. 2018. Retrieved 2019-07-01.

- ^ "Best Regional Universities West Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "2021 Best National University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ 2020 Master's Universities Rankings. Washington Monthly. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ 2020 National Universities Rankings. Washington Monthly. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. August 15, 2019.

- ^ Regional Colleges West Rankings | Top Regional Universities West | U.S. News Best Colleges. Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Retrieved on November 14, 2015.

- ^ CSU Stanislaus | Stockton Center. Stockton.csustan.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ "Desert Studies Center at Soda Springs". fullerton.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-03-15.

- ^ "Moss Landing Marine Labs". calstate.edu.

- ^ SAN BERNARDINO: Observatory to bring the universe to community | San Bernardino County News | PE.com - Press-Enterprise. PE.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-15.

- ^ "Southern California Marine Institute". scmi.net. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ^ "San Diego State University Department of Astronomy". Sdsu.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "Training Ship Golden State". 2004-11-16. Archived from the original on 2004-11-16. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ "HSU Marine Lab". humboldt.edu.

- ^ "LSU Reservations". Archived from the original on October 26, 2014.

- ^ Serpe, Richard (February 2002), "CSU Faculty Workload Report", The Social and Behavioral Research Institute: 21

- ^ Clinthorne, Janice (October 1984), "University of California Faculty Time-Use Study", Institute for Research in Social Behavior: 29

- ^ Smelser, Neil J. (2010). Reflections on the University of California: From the Free Speech Movement to the Global University. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 186. ISBN 9780520946002. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Renny, Christopher (2005). "New Working-class Studies in Higher Education". In Russo, John; Linkon, Sherry Lee (eds.). New Working-class Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 209–219. ISBN 9780801489679. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Berquist, William (2006). "Leadership at the Interest: New Forms of Governance to Oversee New Form of Higher Education". In Anderson, Walter Truett; Dator, James Allen; Tehranian, Majid (eds.). Learning to Seek: Globalization, Governance, And the Futures of Higher Education. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. pp. 82–100. ISBN 9781412806152. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Pickens, William H. (1999). "The California Experience: The Segmented Approach". In Gaither, Gerald H. (ed.). The Multicampus System: Perspectives on Practice and Prospects. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC. pp. 145–162. ISBN 9781579220167. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Wallace, Amy (19 January 1997). "The CEO Higher Learning". Los Angeles Times Magazine. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Kevin Starr, Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990–2003 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 583. ISBN 9780307795267.

- ^ California State Department of Education (1960). A Master Plan for Higher Education in California: 1960–1975. Chapter IV - Students: The Problem of Numbers, p. 46. Retrieved: September 12, 2016.

- ^ "Institution Lookup: San Diego State University". Carnegie Classifications. Archived from the original on 2021-08-25. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ "The University of California Statistical Summary Fall 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ Reed, Ann (Spring 2003). "Donald R. Gerth to leave the Sac State presidency after nearly two decades". Capital University Journal. Archived from the original on 2004-09-23. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ Standing Orders 100.4 and 100.6 of the Regents of the University of California.

- ^ "The 2015–16 Budget: Higher Education Analysis". www.lao.ca.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-01.

- ^ Saavedra, Sherry (September 23, 2007). "As SDSU evolves, demand for housing grows; University was built as commuter campus". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-03-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Cal State joins national trend to switch to 15-week semesters". EdSource. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ "Meeting Notes May 4, 2018, 2002AB Steering Committee of Semester Conversion" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- ^ "2018-2019 ACADEMIC CALENDAR BY SEMESTERS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-28. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- ^ "Q2S Update-Winter/Spring 2017". Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- ^ "Campus Impaction". The California State University. July 23, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "ARTICLE 1. General Provisions [89000 - 89011] - 89001". State of California. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "ARTICLE 1. General Provisions [89000 - 89011] - 89005.5". State of California. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Campus Names". California State University. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "The Cal Poly Name". California Polytechnic State University. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ Connell, Sally Ann (August 17, 2003). "Cal Poly Campus Aims to Keep Its Name, and Profits, to Itself". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ Hamilton, Tracy Idell (February 22, 2001). "Cal Poly v. Bello's". Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ "Campus Names". calstate.edu. California State University. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ "California State University - Campus Websites". calstate.edu.

- ^ Gerth, Donald R.; James O. Haehn (1971). Invisible Giant: The California State Colleges. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. ISBN 0-87589-110-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "CSU NEW STUDENTS (DUPLICATED) APPLICATIONS AND ADMISSIONS BY CAMPUS AND STUDENT LEVEL, FALL 2018". California State University. 12 July 2019.

- ^ "Ethnicity Enrollment Profile". www.calstate.edu. Retrieved 2019-07-09.

- ^ "Impacted Undergraduate Majors and Campuses in the California State University – 2008–2009". The California State University. 2008-01-18. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ CSUMentor - Explore Campuses - Campus Facts - Cal Maritime. Csumentor.edu. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ^ "ABET-Accredited Program Search". ABET. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "California State University Agricultural Research Institute". calstate.edu.

- ^ "California State University Program for Education and Research in Biotechnology (CSUPERB) - CSU". calstate.edu.

- ^ "What Is Graduation Initiative 2025? | CSU". www2.calstate.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- ^ "Improvements in CSU system discussed at Graduation Initiative 2025 Symposium". FOX40. 2019-10-19. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- ^ "Cal State system sees record increases in graduation rates". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- ^ "CSU Degree Programs". Hospitality Management Education Initiative. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "Measuring the Value of CSU". California State University. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ "California Postsecondary Education Commission - Topical Listing". Cpec.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 2006-09-25. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "California State University unveils 'radical' plan for online courses". timesheraldonline.com. Archived from the original on 2013-08-04. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ Cal State to Offer 36 Online Classes to Students Statewide - Yahoo News Archived August 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "California Pre-Doctoral Program - CSU". calstate.edu.

- ^ "Chancellor's Doctoral Incentive Program (CDIP) - Human Resources - CSU". calstate.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-09-06.

- ^ "California State University Program for Education and Research in Biotechnology (CSUPERB) - CSU" (PDF). csuchico.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-05. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Science Masters > ScienceMasters Home". sciencemasters.com.

Further reading[]

- Donald R. Gerth. The People's University: A History of the California State University. Berkeley: Institute of Governmental Studies, University of California, 2010. ISBN 978-0-87772-435-3.

External links[]

Coordinates: 33°45′50″N 118°12′4″W / 33.76389°N 118.20111°W

- California State University

- Public university systems in the United States

- Schools accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges

- Public universities and colleges in California

- Educational institutions established in 1857

- 1857 establishments in California