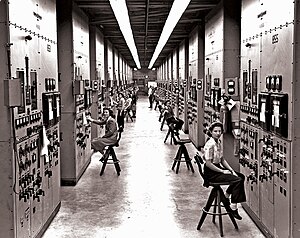

Calutron Girls

The Calutron Girls were a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, who joined the World War II efforts to develop nuclear weapons at the United States government facility located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in 1944 and 1945.[2]

Although they were not allowed to know at the time, they were monitoring dials and watching meters for a calutron, a mass spectrometer adapted for separation of uranium isotopes. In this way, the Calutron Girls were responsible for process control for the isotope enrichment operation.[3] The enriched uranium was used to make the "Little Boy" atomic bomb for the Hiroshima nuclear bombing on August 6, 1945.

The Calutron Girls were trained and employed at the Y-12 National Security Complex.[4] Wartime labor shortages forced the Tennessee Eastman Corporation to hire women to work at the Y-12 plant. Most of them were from towns in east Tennessee, although young women from elsewhere in the United States also became Calutron Girls.[5] They were enticed to these jobs by good pay and affordable housing, by the standards of women at the time and in the region.[6]

The Calutron Girls were told by their employer that they were working for the Clinton Engineer Works, often known by the acronym CEW, which was a front for the Manhattan Project.[6] At its employment peak in 1945, approximately 75,000 people worked at Oak Ridge under the guise of the Clinton Engineer Works. A very large portion of the workers were women. Of these, approximately 22,000 employees worked on the Y-12 facility. The women among them were the group considered the "Calutron Girls". [7]

Secrecy and confidentiality were a strict requirement of their employment.[6] According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them: "We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!"[8]

Even though the Calutron Girls were unaware that they were working on isolating fissionable uranium isotopes for weapons manufacture, they were directed to maintain the equipment and instrumentation at key set points. While they did not know the significance of the set points they controlled the instrumentation for, they knew from their training that readings in the "R" range were good, a reading of "E" was that the system was collecting the desired product, and that all other readings necessitated that they make adjustments to the equipment according to prescribed procedures. In this way, the Calutron Girls were critical to process control of the Y-12 facility.[7]

Another calutron device existed at the time in a laboratory at the University of California at Berkeley, led by physicist Ernest O. Lawrence. The facility there was operated by trained professional physicists. As the Y-12 calutron facility at Oak Ridge became operational, Lawrence desired that it be also run by trained professional physicists. Because of the labor shortage during World War II, the staffing went to the Calutron Girls. In a comparison, the Calutron Girls outperformed the trained professional physicists in efficiency of calutron operation. The better performance of the Calutron Girls was attributed to the intense focus of the Calutron Girls to maintaining precise control as opposed to the physicists who were distracted by chasing operational problems.[7]

The word "calutron" is a portmanteau of California University Cyclotron.[9]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calutron. |

References[]

- ^ Yifat Gutman; Adam Brown; Amy Sodaro (6 October 2010). Memory and the Future: Transnational Politics, Ethics and Society. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 168–. ISBN 978-0-230-29233-8.

The image of the Calutron Girls and the rest of the collected photographs offer a very idealized version of the work that was done at the atomic factories, even the ... Ed Westcott, Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

- ^ Lindsey A. Freeman (13 April 2015). Longing for the Bomb: Oak Ridge and Atomic Nostalgia. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-1-4696-2238-5.

- ^ Diane Fanning (1 November 2014). Scandal in the Secret City: A World War Two mystery set in Tennessee. Severn House Publishers. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-1-78010-568-0.

- ^ Duane S. Nickell (2010). Guidebook for the Scientific Traveler: Visiting Physics and Chemistry Sites Across America. Rutgers University Press. pp. 142–. ISBN 978-0-8135-4730-5.

These “calutron girls” were trained to sit and watch meters on the control panels and make adjustments if the needles moved too far in one direction or the other. ... At Oak Ridge, the diffusion process was housed in the titanic K-25 building.

- ^ "Ruth's Story", United States Department of Energy, June 5, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Who Were the Calutron Girls of Oak Ridge?". exploreoakridge.com. Oak Ridge CVB. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "A Book Review of The Girls of Atomic City by Denise Kiernan". nationalww2museum.org. National World War II Museum. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ Smith, Ray. "The Calutron Girls". smithdray1.net. Ray Smith. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ Henderson, Nancy. "Girl Power, Circa 1940: Building The Bomb (and Not Knowing It) in East Tennessee". blueridgecountry.com. LeisureMedia360. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

Further reading[]

- Denise Kiernan (11 March 2014). The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-1753-5.

- Ray Smith (9 February 2013). 2006 Historically Speaking : As published in the Oak Ridger Newspaper. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-1-257-23331-1.

External links[]

- American women in World War II

- Isotope separation

- Manhattan Project people

- Oak Ridge, Tennessee

- Women in Tennessee

- Women by organization

- 20th-century American people

- Women on the Manhattan Project