Cannibalism in pre-Columbian America

The examples and perspective in this article or section may not represent an indigenous view of the subject. (August 2020) |

There is universal agreement that some Mesoamerican people practiced human sacrifice and cannibalism, but there is no scholarly consensus as to its extent.

At one extreme, anthropologist Marvin Harris, author of Cannibals and Kings, has suggested that the flesh of the victims was a part of an aristocratic diet as a reward, since the Aztec diet was lacking in proteins. According to Harris, the Aztec economy would not support feeding slaves (the captured in war) and the columns of prisoners were "marching meat".

Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano has proposed that Aztec cannibalism coincided with times of harvest and should be thought of as more of a Thanksgiving. Montellano rejects the theories of Harner and Harris saying that with evidence of so many tributes and intensive chinampa agriculture, the Aztecs did not need any other food sources.

At the other extreme, William Arens doubts whether there was ever any systematic cannibalism.[1]

Aztec cannibalism[]

The Mexica of the Aztec period are perhaps the most widely studied of the ancient Mesoamerican peoples. While most pre-Columbian historians believe that ritual cannibalism took place in the context of human sacrifices, they do not support Harris' thesis that human flesh was ever a significant portion of the Aztec diet. Michael D. Coe states that while "it is incontrovertible that some of these victims ended up by being eaten ritually […], the practice was more like a form of communion than a cannibal feast".[2]

Documentation of Aztec cannibalism mainly dates from the period after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519-1521):

In The Man-Eating Myth, Arens writes, "The gradual transformation of what little evidence is available for Aztec cannibalism is also an indication of the continual need to legitimize the Conquest".[3] The following claims could have been exaggerated.

- Hernán Cortés wrote in one of his letters that a Spaniard saw an Indian...eating a piece of flesh taken from the body of an Indian who had been killed.[4]

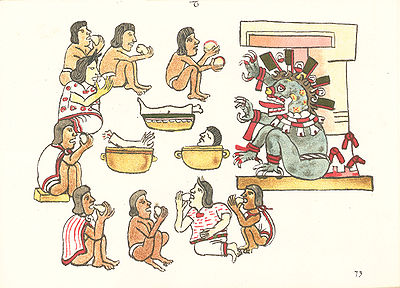

- The Historia general (compiled 1540-1585) by Bernardino de Sahagún (the first Mesoamerican ethnographer, according to Miguel León-Portilla) contains an illustration of an Aztec being cooked by an unknown tribe. This was reported as one of the dangers that Aztec traders faced.

- In his book Relación (1582), Juan Bautista de Pomar (c. 1535 – 1590) states that after the sacrifice the body of the victim was given to the warrior responsible for the capture. He would boil the body and cut it to pieces to be offered as gifts to important people in exchange for presents and slaves. It was rarely eaten, since they considered it of no value. Bernal Díaz reports that some of these parts of human flesh made their way to the Tlatelolco market near Tenochtitlan.

- In 2012 The National Institute for Anthropology and History (INAH) reported that they have discovered around 60 skeletons under subway lines in Mexico City, 50 children, and 10 adults, dating back 500 years. The skeletons appear to have cut marks on the bones that indicated human sacrifice, but does not indicate that cannibalism had occurred.[5][6]

Bernal Díaz's account[]

Bernal Díaz's The Conquest of New Spain (written by 1568, published 1632) contains several accounts of cannibalism among the people the conquistadors encountered during their warring expedition to Tenochtitlan.

- About the city of Cholula, Díaz wrote of his shock at seeing young men in cages ready to be sacrificed and eaten.[7]

- In the same work Diaz mentions that the Cholulan and Aztec warriors were so confident of victory against the conquistadors in an upcoming battle the following day, that "...they wished to kill us and eat our flesh, and had already prepared the pots with salt and peppers and tomatoes".[8]

- About the Quetzalcoatl temple of Tenochtitlan Díaz wrote that inside there were large pots, where human flesh of sacrificed Natives was boiled and cooked to feed the priests.[9]

- About the Mesoamerican towns in general Díaz wrote that some of the indigenous people he saw were:

eating human meat, just like we take cows from the butcher’s shops, and they have in all towns thick wooden jail-houses, like cages, and in them they put many Indian men, women and boys to fatten, and being fattened they sacrificed and ate them.[10]

Díaz's testimony is corroborated by other Spanish historians who wrote about the conquest. In History of Tlaxcala (written by 1585), Diego Muñoz Camargo (c. 1529 – 1599) states that:

Thus there were public butcher's shops of human flesh, as if it were of cow or sheep.[11]

Controversy[]

Accounts of the Aztec Empire as a "Cannibal Kingdom", Marvin Harris's expression, have been commonplace from Bernal Díaz to Harris, William H. Prescott and Michael Harner. Harner has accused his colleagues, especially those in Mexico, of downplaying the evidence of Aztec cannibalism. Ortiz de Montellano[12] presents evidence that the Aztec diet was balanced and that the dietary contribution of cannibalism would not have been very effective as a reward.

Cannibalism among the Xiximes[]

As recently as 2008, Mexico's National Institute of Archaeology and History (INAH) derided as a "myth" historical accounts by Jesuit missionaries reporting ritual cannibalism among the Xiximes people of northern Mexico.[13] But in 2011, archaeologist José Luis Punzo, director of INAH, reported evidence confirming that the Xiximes did indeed practice cannibalism.[14]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Arens, William (1979-04-26). The Man-Eating Myth : Anthropology and Anthropophagy: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199763443.

- ^ Coe, Michael D.; Koontz, Rex (2008-01-01). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500287552.

- ^ Arens, William (1979-04-26). The Man-Eating Myth : Anthropology and Anthropophagy: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199763443.

- ^ Letters of Cortés, trans. Francis A. MacNutt (New York: 1908), 1:256-257, 2:244.

- ^ "Under Mexico City - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ^ "Mexico City Subway Dig Yields Aztec Remains and Artifacts - History in the Headlines". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ^ Díaz del Castillo [c.1568](1992, p.150).

- ^ Diaz del Castillo, Bernal [c.1568](1956, p.178), The Discovery And Conquest Of Mexico, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy USA oclc 56-5758

- ^ Díaz del Castillo [c.1568](1992, p.176).

- ^ Díaz del Castillo [c.1568](1992, p.579). In the original Spanish: "[...] comer carne humana, así como nosotros traemos vaca de las carnicerías, y tenían en todos los pueblos cárceles de madera gruesa hechas a manera de casas, como jaulas, y en ellas metían a engordar muchas indias e indios y muchachos, y estando gordos los sacrificaban y comían."

- ^ Excerpt translated from Muñoz Camargo [c.1585](1947, p.153). In the original Spanish: "Ansí había carnicerías públicas de carne humana, como si fueran de vaca y carnero como en día de hoy las hay […]".

- ^ Ortiz de Montellano, B.R. "Aztec Cannibalism: An Ecological Necessity," Science, 200, 611-617.1978

- ^ "Sinaloa Xixime people's Cannibalism, A Myth". Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. 9 June 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

Sinaloa INAH Center archaeologist Alfonso Grave Tirado declared that Spaniard chroniclers’ appreciations reflected fear inspired by Xixime, and not a historical reality.

- ^ Valle, Sabrina (1 October 2011). "Cannibalism Confirmed Among Ancient Mexican Group". National Geographic. The National Geographic Society. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

The newfound bones prove that cannibalism, 'was a crucial aspect of their worldview, their identity,' said José Luis Punzo, an archaeologist behind the new research.

References[]

- Arens, William (1980). The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502793-0.

- Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (1963) [1632]. The Conquest of New Spain. Penguin Classics. J. M. Cohen (trans.) (6th printing (1973) ed.). Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044123-9. OCLC 162351797.

- Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (1992) [1632]. (in Spanish). Joaquín Ramírez Cabañas (ed., intro. & notes). México D.F.: Editorial Porrúa. ISBN 970-07-1800-X.

- Harner, Michael (Apr 1977). "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice" (online reproduction at latinamericanstudies.org). Natural History. 86 (4): 46–51. ISSN 0028-0712.

- Harris, Marvin (1991) [1977]. Cannibals and Kings: Origins of Cultures (Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-72849-X. OCLC 23985455.

- Muñoz Camargo, Diego (1947) [ca. 1585]. Historia de Tlaxcala (in Spanish). México D.F.: Publicaciones del Ateneo Nacional de Ciencias y Artes de México.

- Cannibalism in North America

- Pre-Columbian cultures

- Mesoamerican diet and subsistence