Carol M. Highsmith

Carol M. Highsmith | |

|---|---|

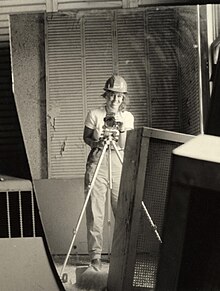

Carol M. Highsmith self portrait in front of a broken mirror at the Willard Hotel in 1980 | |

| Born | Carol Louise McKinney May 18, 1946 Leaksville, North Carolina, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Minnehaha Academy |

| Alma mater | American University |

| Known for | Photography Collection of America |

| Patron(s) | George F. Landegger; The Capital Group Foundation in memory of its late chairman, Jon B. Lovelace; Lyda Hill of Dallas, Texas; The Gates Frontiers Fund; The Ben May Family Foundation; Craig and Barbara Barrett; Pew Charitable Trust; The Library of Congress |

| Website | CarolHighsmithAmerica.com ThisIsAmericaFoundation.org |

Carol McKinney Highsmith (born Carol Louise McKinney on May 18, 1946) is an American photographer, author, and publisher who has photographed in all the states of the United States, as well as the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. She photographs the entire American vista (including landscapes, architecture, urban and rural life, and people in their work environments) in all fifty U.S. states as a record of the early 21st century.

Highsmith donated her life's work of more than 100,000 images, royalty-free, to the Library of Congress, which established a rare, one-person archive.[1][2]

Early life and studies[]

Childhood[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Carol Louise McKinney was born to Luther Carlton McKinney and Ruth Ragsdale Carter in Leaksville, North Carolina near the large tobacco farm owned by her maternal grandparents, Yancey Ligon Carter and Mary Elizabeth Morton. Her mother's family were planters descending from the colonist Thomas Carter and owned a plantation near Wentworth, North Carolina.[4] Her father was a manufacturer representative and her mother worked for Billy Graham.[5] She is a first cousin of the journalist Linda Carter Brinson and the visual artist Benny Carter, as well as a niece of Lieutenant-Colonel J.P. Carter.[6]

In an hour-long interview with C-Span founder and host Brian Lamb on July 17, 2011,[3] Highsmith spoke extensively of her childhood in Minneapolis, where she grew up, and her summers in the South. She and her sister Sara would spend the first half of summer on their maternal grandmother's North Carolina tobacco farm and the second half as part of the high society of Atlanta, Georgia. Highsmith said that her paternal grandmother, also named Sara McKinney, was a friend of Margaret Mitchell and other society women. "We'd spend every day at someone's pool or country club," Highsmith said. "Opera played on the radio. Grandmother taught us manners and etiquette—to sit up straight, eat with our mouths closed, hold the soup spoon just so."[3]

Highsmith said that her rural "granny" in North Carolina was wealthier than her refined grandmother in Atlanta. "Granny and Granddad owned a large and successful tobacco farm," Highsmith said. "Grandmother and grandfather [in Atlanta], had lost everything [including his furniture business] in two fires and the Great Depression. But grandmother's friends made like nothing had happened. They'd have her to dinner, play bridge and canasta, even take her on cruises to Europe and have their chauffeurs drive her as if she were still part of the aristocracy."[3]

Highsmith told C-Span that the influence of her father, a traveling salesman, and her own annual travels through several states to reach her grandmothers imbued her with a fascination about America, "especially roadside America. The old car in which my mother would drive Sara and me South would break down every year, it seemed, in little towns. We'd have to stay overnight in little motels and above the kinds of old gas stations I love to photograph today."[3]

In February 2012, Carol Highsmith returned to her birth city in North Carolina to record a tape about her childhood experiences. It was played four months later at the opening of the Museum and Archives of Rockingham County (MARC) in Wentworth. The museum's newsletter called it "the journey of a hometown girl."[7] Highsmith's summer trips to her granny's farm "left an indelible memory of carefree days, delicious food, and wonderful times with family and friends," it continued.[7] Highsmith's experiences in rural Rockingham County were also recounted in a lengthy feature story about her life and career in the Greensboro, N.C., News & Record on August 5, 2017. The article, by Dawn DeCwikiel-Kane, included Highsmith's reflection on the significance of her (then) 25-year donation of more than 42,000 images to the Library of Congress: "'It's my legacy,' she said. "But it's our [nation's] legacy.'" The story, entitled "America's Photographer," won a 2017 first-place award in the Profile Feature category in an annual contest sponsored by the North Carolina Press Association.[8]

Carol Highsmith (then McKinney) graduated from the private, Christian Minnehaha Academy in Minneapolis in 1964, then studied for a year in college at the now-defunct Parsons College in Fairfield, Iowa. In a 2013 profile of Highsmith, the Minnehaha Academy alumni magazine, the Arrow, quoted Highsmith:

The 1960s were a magical time. They remind me of what I've read about the liberating, transitional 1920s. We were at the right age to be profoundly affected by the churning changes in our times. Little did we know how profound and lasting would be the effects of the civil rights movement, landing a man on the moon, the rock'n'roll revolution, the Vietnam War and the protests against it, the social and counterculture movement, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Kennedy Brothers. I am the driven, creative, and somewhat unpredictable person I am partly because of those rebellious times, framed against the backdrop of solid, values-oriented Midwest surroundings. When I attended Minnehaha Academy, I was voted Most Mischievous! Perhaps there's a lesson there—that anyone, even average, fun-loving students, can achieve a life of substance, given determination and half a chance.[9]

College, marriage, and career[]

At Parsons College, Carol McKinney met Mark Highsmith, an artist from Queens, New York, who soon graduated and enlisted in the Army. The couple married in Minneapolis, then moved to Columbus, Georgia, where Mark Highsmith was stationed at Fort Benning. Upon his deployment to Vietnam in 1966, Carol Highsmith moved to Queens after securing a position at Peters Griffin Woodward, a national radio "rep" firm in Manhattan. As an assistant traffic manager at its Park Avenue offices, she logged advertisements for radio stations across the country. It was Highsmith's introduction to her first career in the broadcasting business.[10]

Early marriage and career[]

When Mark Highsmith returned from Vietnam in 1967, he was assigned to Fort Bragg, and the couple briefly moved to Fayetteville, North Carolina. Shortly thereafter, Mark Highsmith was discharged from the Army, and the Highsmiths relocated to Philadelphia, where he enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Carol Highsmith worked at WPHL-TV, the home of the "Summertime at the Pier," a teenage dance show hosted by Philadelphia disc jockey Ed Hurst on Atlantic City's Steel Pier in nearby New Jersey.

Highsmith wrote promotional copy and produced shows. One of her jobs was to assist Bill "Wee Willie" Webber on his children's show, the Wee Willie Webber Colorful Cartoon Club, Highsmith was pictured in a Philadelphia Inquirer advertisement for the station, strumming a guitar. "Take Over a TV Station (for 50 seconds)," the ad copy read. "TV 17 doesn't care who you are. How old you are. Or how you think. As long as you or your group can write and sing music.... So if you really care, stop griping. And start writing."

In 1969, Highsmith heard on the radio, at a time when stations were reporting such events, that her husband had committed suicide in his art studio.[10] Mark had returned from Vietnam with posttraumatic stress disorder. Determined to get her college degree, she moved to KYW-TV in broadcast sales. KYW paid for more college coursework at the University of Pennsylvania, on nights and weekends.

Early career[]

Broadcasting[]

In 1976, Highsmith moved to Washington, D.C., and spent six years as a senior account executive for radio station WMAL while taking classes at American University. She served on boards of directors including that of the Greater Washington Board of Trade[11]

By 1979, Highsmith won a national contest initiated by the Radio Advertising Bureau in New York for the nation's most unusual sales effort.[citation needed] This stemmed from broadcasts from London and the Oktoberfest in Germany that she had devised and organized. She traveled with the broadcast team on both trips. ABC ran a full-page ad in The New York Times promoting one of the broadcasts from London.[citation needed]

One year at Oktoberfest in Munich, she recalled in a portfolio of her life's "experiential learning" that she would submit for college credits at American University, "we broadcast from a different beer tent each night from a table with 6,000 drunk Germans singing around us. Since we had a language barrier, we could not easily interview people as we had [on another trip] in London. However, we did arrange some interesting interviews with Germans who spoke English. We interspersed the live cut-ins with German tunes, and our loyal listeners joined in back home."[12]

Soon photography would rise to the forefront of her life. The career change began in 1980, when she was named WMAL's Employee of the Year. Highsmith decided to apply the $1,000 prize award toward a trip to the Soviet Union. A longtime client gave her an inexpensive Pentax K1000, a small, manual-focus single-lens reflex camera that shoots 35-millimeter film. Highsmith snapped photographs from Kiev to eastern Siberia.[citation needed]

Beginning of photography[]

Back in the States working as a senior account executive in broadcasting, Highsmith was determined to further explore photography while completing an undergraduate degree. She studied photography at American University under Professor Anne Zelle and took night-school photography classes, taught by photographer Frank DiPerna, at the Corcoran College of Art and Design.[13]

DiPerna assigned each class member to photograph a model in an unusual location in metropolitan Washington. Highsmith chose the crumbling Willard Hotel, which had been closed since 1968.[14][15] Her mostly black-and-white photos taken there reaffirmed her eye for detail and solidified her interest in photographic art.[16]

Carol M. Highsmith and Frances Benjamin Johnston[]

It was at the Willard that Highsmith first learned of Frances Benjamin Johnston, and where she began her photography career. The once-opulent hotel was deserted, stripped of its furnishings and fixtures, and slated for demolition. "[The Willard's] main tenant was a bum who was setting fires on the sixth floor," Highsmith told the New York Times when the newspaper recounted the hotel's long history in 2006. "There were rats the sizes of cats. If I didn't take pictures, what would it look like in a few more years?"[17] In its Winter 1995 issue, Old House Interiors magazine also quoted her: "I started to think, if this can happen to America's Main Street, what other buildings are decaying that we don't even know about, and who's documenting them?".[18]

Frances Benjamin Johnston became Highsmith's professional inspiration.[16] Johnston, too, had done a full study of the Beaux-Arts hotel in 1901, when it expanded from 100 to 389 rooms. When the decrepit Willard was finally saved through the efforts of a spirited "Don't Tear it Down" campaign, and then restored for its reopening in 1986, the only record available to those who re-created many of the hotel's lavish features were Johnston's faded, black-and-white images. Not a single blueprint or artist's drawing had survived the gutting of the historic hotel.[18]

"I was sucked into a moment of history," the Washington media quoted Highsmith in a 1988 profile. "I didn't care if I got paid. I didn't care if I ate. I had to take those photographs. When the Willard opened, people called me from all over the world. I was the only one who had any images of the famous hotel."[citation needed]

For a year after the grand hotel re-opened, it displayed an extensive exhibit of Highsmith and Johnston's work in an alcove off the "Peacock Alley" corridor.[19] That exhibit remains as a permanent collection in smaller form.

In 2006, the American Institute of Architects would mount a four-month comparative exhibit of Highsmith and Johnston's work called "Two Windows on the Willard." Like another AIA one-person exhibit of Highsmith's work, titled "Structures of our Times: 31 Buildings That Changed Modern Life" in 2002, the "Two Windows" study traveled to several locations across the country.[20]

By that time, Highsmith was well into her photography career, having left radio behind in 1984. She had pieced together a small, primarily architectural, photography practice.

In a 1987 Washington Post story headlined, "Doing What Comes Naturally," Don Oldenburg wrote of Highsmith's mid-career change:

"'You just sit and stare into space and think about what you'd really like to be doing,' the 41-year-old District resident recalls of her final months at WMAL radio five years ago. That was before she quit to make her dream career come true. She wanted to be a photographer....

"Ironically, those dreams of the ideal occupation that now and then distract most people from the workday grind, have traditionally been derided as detours from the American Dream. Those few individuals who actually act on their career fantasies have long been considered ne'er-do-wells, malingerers and daydreamers. Until they succeed. . . . 'It carved out a niche for me,' says Highsmith from her studio at 13th and G streets NW, where she employs seven assistants and charges up to $1,500 a day. The Willard photographs already are destined to become part of the photographic archives of architecture at the Library of Congress. Highsmith says she still gets goose bumps to think she's a professional photographer.

"Bob Swain believes that people like Highsmith, who make their fantasies their business, are 'the wave of the very near future.' The chairman of Swain & Swain Inc., a New York outplacement firm, bases that prediction partly on a recent survey he conducted of his clients—predominantly midlevel managers and professionals who have been 'displaced' by their corporations and sent to Swain for career counseling.

"'Eighty-two percent of them admitted wanting to do something like that ... there is clearly a tendency to fantasize,' says Swain. 'Eighteen percent actually do it.'"[21]

Asked her personal motto by the Washington Times in 1989 in one of the newspaper's periodic profile of "doers," Highsmith replied, "A little hard work never hurt anyone."[22]

Various projects[]

Highsmith landed a contract to photograph another building on Pennsylvania Avenue. It was a turreted building called Sears House, where Mathew Brady had operated the studios in which he and his assistants photographed Washington luminaries during and after the Civil War. Her work at Sears House would lead to Highsmith's first photographic honor, a 1985 Award of Excellence from Communication Arts magazine.[23]

In 1987, Highsmith's tie to "The Avenue of Presidents" solidified when she was hired by the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Commission to document its wave of renovations on the avenue.[24]

Pennsylvania Avenue: America's Main Street, published by the American Institute of Architects' AIA Press in 1988, became the first of her dozens of books. Detailing the transition of the avenue's south side into the "Federal Triangle" and the methodical redevelopment of its shoddy north side, the book was augmented by historic photographs and a text by Ted Landphair—who had been WMAL's news director in the 1970s but barely knew Highsmith before leaving the station to work in other markets.

When Landphair returned to Washington to join the Voice of America in 1986, he and Highsmith reconnected, and they married two years later as the Pennsylvania Avenue book was going to press. Carol M. Highsmith had added a collaborator husband and four stepchildren to her busy life.

"As you both know, it took forty years, eight presidents, and a great succession of Congressional enactments" to "revive the Avenue," U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who had spearheaded Pennsylvania Avenue's renovation since his days as an aide to President John F. Kennedy in the 1960s, wrote Highsmith and Landphair in 2000. "And you deserve a considerable share of the credit."[citation needed]

In 1992, the Library of Congress accepted 500 of Highsmith's photographs as the first installment of her continuing work to document architectural transitions in the nation's capital.[25] The collection would grow and become nationwide as Highsmith began to travel to other states to produce photographs for her books on American cities, states, and regions.

That same year, 1992, the D.C. Preservation League exhibited Highsmith's cibachrome photos of Washington historic landmarks. "Her camera peers into dark, shaded porches in a shot of turn-of-the-century houses ... then glances down the clapboards of spare, wooden row houses build a decade before," the Washington Post reported.[26] "With the exception of a canal boat gliding along the C&O [Canal], there's nothing touristy here. It's Washington as the locals know it."

And in 1992 as well, the National Endowment for the Arts presented Highsmith with its largest individual grant, a $20,000 Design Arts fellowship and individual project award.[27] The award funded her and Landphair's travels to the western United States, including Alaska and Hawaii, to photograph examples of historic restoration for the America Restored book.

Highsmith deepened her affinity for architecture by documenting various stages of buildings' renewal for contractors, architects, and developers. "Shooting enormous spaces in uncertain lighting conditions, her large format images reveal high quality and fine detail, capturing the splendor of the subject matter, be it a building in the midst of destruction or the elegance of a formal room," American Photographers magazine commented in 1989.[28]

From 2000 to 2002, a three-year grant from the Annie E. Casey Foundation enabled Highsmith to photograph disadvantaged families in 22 cities where the foundation is active.[29]

Later, the library's online Prints & Photographs Catalog description of the growing Carol M. Highsmith Archive noted that, "starting in 2002, Highsmith provided scans or photographs she shot digitally with new donations to allow rapid online access throughout the world. Her generosity in dedicating the rights to the American people for free access also makes this Archive a very special resource".[2]

In March 2009, the Library of Congress profiled four women, including Highsmith, during Women's History Month. The others were suffragist leader Susan B. Anthony, early-20th-century magazine illustrator Elizabeth Shippen Green, and retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor.[30]

Highsmith's travels took her to more remote destinations, capturing covered bridges from Vermont to Indiana, murals and neon figures, classic cars and old motor courts and a giant blue concrete whale along U.S. Route 66, "doo wop" motels on the New Jersey shore, a mining tipple in Wyoming and shuttered gas stations in Southside Virginia, abandoned steel mills and plantation ruins in Alabama, kudzu-covered barns in the Carolinas, roadside curiosities such as a four-story donut and a giant "Aunt Jemima" that is now a gift shop, storefront churches and drive-in theaters and brick sections of the old National Road alongside a modern interstate highway.[31]

From this work, she developed a subspecialty that she calls "Disappearing America."[32] "After interviewing Highsmith as she was photographing the Torrey Pines Golf Course in 2013, San Diego Union-Tribune reporter John Wilkens wrote: "She ... has a passion for things that are disappearing, which made the tree the golf course is named after an appealing focal point. The Torrey is the rarest pine in the U.S."[33]

"I work every day with a heartfelt commitment to document the living history and built environment of our times," Highsmith told officials of the This is America! Foundation, which is raising funds to send her on yet another 50-state photographic exploration. "I consider my work an indestructible record of our vast nation, including sites that are fast fading, even disappearing, in the wake of growth, development, and decay."[34]

Photography career[]

According to C. Ford Peatross, director of the Center for Architecture at the Library of Congress, "The donation of Carol Highsmith's photography is one of the greatest acts of generosity in the history of the Library of Congress."[35] In 2013, Peatross told the San Diego Union-Tribune newspaper, "[She] is not only taking photographs but creating a permanent record of the country and its people for the common good."[36]

On April 28, 2013, the CBS television news magazine "CBS This Morning" featured Highsmith's work in a lengthy segment titled, "Saving America for Posterity at the Library of Congress". CBS Correspondent Martha Teichner told in her report: "Highsmith is at work on a decades-long project photographing all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Her pictures, thousands of them, are going to the Library of Congress and are being made available free for anyone to use."[37] The CBS Sunday Morning report continued, "Highsmith's images also capture a disappearing America. Two weeks after she photographed Big Tex, the mascot of the Texas State Fair, he burned down. Her photograph of the New York skyline, just before 9/11, is also in the Library of Congress."[38] CBS included more than 30 of Carol's images in the online version of its report.[38]

In its December 2007 issue, the Library of Congress's Information Bulletin included a "Conversation with Carol Highsmith." In the article, Jeremy Adamson, the director of Collections and Services at the library, said, "Highsmith's color images are certainly of the highest technical and artistic quality. But more importantly, she has the uncanny ability to identify, focus on and capture for posterity the essential features of our social landscape and physical environment, both natural and man-made. A photograph by Carol Highsmith is a document of rare precision and beauty, revealing with exacting clarity the look and feel of people and places across our great nation."[39]

Professional photography and publishing[]

Her work has been featured in more than 50 hardback coffee-table books, most published by Crescent Books, an imprint of Random House in New York, and by Preservation Press, the publishing arm of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Highsmith also photographed, and her publishing company, Chelsea Publishing, Inc., published six additional books: Forgotten No More, about the Korean War Veterans' Memorial;[40] Union Station: A Decorative History, about Washington's historic train terminal;[41] Reading Terminal and Market: Philadelphia's Gateway and Grand Convention Center;[42] The Mount Washington: A Century of Grandeur; and Houston: Deep in the Heart.

Early in her career, Highsmith photographed interior and exterior architecture. But as she and her writer-husband, Ted Landphair, traveled the country to every state and major city to work on the Random House "Photographic Tour" and smaller "Pictorial Souvenir" book series, her scope broadened to be a photographic documentarian. She photographed ordinary people and everyday sites as well as soaring architecture, natural landscapes, national parks and monuments, Civil War battlefields, and engineering marvels.[43]

Her book subjects included the cities San Francisco, New Orleans, Washington, and Chicago; New York's five boroughs; the states of Florida, Colorado, and Virginia; the Pacific Northwest and New England Coast; as well as lighthouses, barns, Amish culture, and the Appalachian Trail.[44]

In 1998, Random House sent Highsmith and Landphair to Ireland, where they photographed every county of Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic, for Ireland: A Photographic Tour, their only book set outside the United States.[45]

In early 2002, Crescent Books published World Trade Center: Tribute and Remembrance, about the 2001 September 11 attacks in New York and exclusively featuring Highsmith's photographs. She had taken aerial photographs of the Twin Towers two months before they fell.[46]

That same year, Highsmith and Landphair collaborated on Deep in the Heart, a book about Houston, Texas, financed by that city's International Protocol Alliance. They also produced The Mount Washington: A Century of Grandeur, on the White Mountains resort. Highsmith collaborated with architectural writer Dixie Legler on Historic Bridges of Maryland, published by that state's department of transportation.[47]

In 2007, Highsmith photographed, and author Ryan Coonerty described, 52 monuments and other public sites in a National Geographic book Etched in Stone.[48]

Having previously privately produced a 265-page coffee-table book for the funder of her photographic excursion to the state of Alabama in 2010, Highsmith in 2013 produced a similar book, with a foreword by Librarian of Congress James Billington and short text by California historian Kevin Starr, about the Golden State. Entitled "California," it was published by Chelsea Publishing, Inc., and publicly sold.[49]

Library of Congress[]

In 2009, the Library of Congress acquired Carol Highsmith's 21st Century America "born digital" collection (photographs that originated in the digital format rather than as film transferred to digital) and expect it to grow to the largest photographic born digital collection at the Library of Congress. This archive, "Carol M. Highsmith's America: Documenting the 21st Century", includes 1,000 images taken across the country. The collection emphasizes what Highsmith calls "Disappearing America," including 200 shots taken along U.S. Route 66 in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma.[16]

"The more she travels across the country, the more convinced she is about the need to capture in photographs a rapidly changing America," noted a Library of Congress bulletin. "'The America I knew is disappearing at lightning speed,' [Highsmith] observed."[16]

Highsmith also produced a visual study consisting of more than 400 color digital photographs of the Library of Congress's own, iconic Thomas Jefferson Building, which opened in 1897, toward the end of America's "Gilded Age" of ornate architecture.[50]

In February 2010 Highsmith began a journey to photograph every state in the United States—state by state in months-long studies, all in her lifetime in a series to be called "This is America,"—also donating these images, free of royalties, to the Library of Congress. "She acknowledges that getting all 50 is going to take a while—15 more years, by her estimate," would write CityLab magazine, the online publication of The Atlantic magazine, five years later. "But Highsmith's not deterred, nor will she narrow her scope. 'Everywhere is important,' she says. 'You tell me I don't need to go to Joplin, Missouri? Things happen. Things change. I will work on this until I die.'"[51]

Highsmith is sometimes called "America's Photographer," most recently in a banner headline in an August 15, 2017 story about her career in the print edition of the Greensboro, North Carolina, News-Record newspaper. "So far, Highsmith has donated about 42,000 photographs to the Library of Congress," the newspaper reported. "She aims to donate 100,000 images before she's done. 'It's my legacy," she said. "But it's our [nation's] legacy.'"[52]

The first state in Highsmith's "This is America" study Alabama became the George F. Landegger Alabama Library of Congress Collection.[53]

George F. Landegger also donated funds to the Library of Congress to document Washington, D.C. neighborhoods[54] and the state of Connecticut.[55] The Connecticut study, intermingled with Highsmith's examinations of the two states (California and Texas) that followed Alabama. The Connecticut work, completed in 2015, culminated in both an archive of Highsmith images in the Library of Congress collection and a coffee-table book, simply titled Connecticut, published by Chelsea Publishing Inc. the same year.[56]

On two photographic expeditions over a six-month period, first in late 2012 and then in early 2013, Highsmith worked in California, producing images for her Library of Congress collection.[57] This body of work, titled The Jon B. Lovelace California Library of Congress Collection, was donated in honor of Lovelace, who died in 2011. Lovelace managed the Capital Group and was chairman of the J. Paul Getty Trust.[58]

In an April 16, 2013, news release from the California Department of Parks and Recreation, Jenan Saunders, California's deputy state historic officer, wrote of Highsmith's work in the Golden State, "Highsmith's efforts produced glorious views of California's lush valleys and rocky shores, forbidding deserts, remarkable buildings, bountiful fields and stunning state and national parks. Her eye fell often on California's state parks. There are images from more than 35 California State Parks included in the visual compilation, from Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park on the north coast to Salton Sea State Recreation Area in the south."[59]

Also in 2013, Artepublishing, a division of the fine-art book publisher Hugh L. Levin LLC, produced an electronic book, "Great Photographs From the Library of Congress," that included more than 700 images from the library's Prints & Photographs Division. Most were black-and-white historical photos, going back to the Civil War work of Mathew Brady, but 22—more than any devoted to any other photographer—were chosen from Carol M. Highsmith's archive of late-20th- and early-21st-century photographs.[60]

In June 2015, Highsmith began work in her fifth and sixth states—Colorado and Wyoming—to be visually studied in depth. The plan for this work calls for return working trips to these states in January 2016 and again in June 2016. These photographic explorations are underwritten by the Gates Frontiers Fund, a private, Colorado-based charitable organization.[61]

Upon her return to her Washington, D.C.-area home in October 2015, Highsmith was the keynote speaker in the first of several planned online seminars (or "Webinars,") organized by the Library of Congress's Education Division. She described her career and answered online attendees' questions about possible applications of her collection to the classroom.[62]

Inspiration[]

Carol M. Highsmith was directly influenced by two female photographers: Frances Benjamin Johnston and Dorothea Lange.[10]

Johnston produced studies of southern plantations, African-American and American Indian schools, national parks, and studio portraits of prominent Americans from the 1890s to 1950s.[63] Highsmith became aware of Johnston's work in the early 1980s, following her first significant photography commission that took her into Washington's Willard Hotel in the early 1980s. There, she learned not only that Johnston had photographed the Willard at the time of its grand reopening in 1901, but also that her photos were the only available record from which artisans could recreate its early grandeur when the hotel was once again restored after nearly falling to the wrecker's ball during Highsmith's time there nearly a century later.[16] It was during this time that Highsmith was told about Johnston's donation of her lifetime body of photographic work to the Library of Congress; she immediately informed the Library's Prints & Photographs Division's curators that she intended to do likewise.[16]

Lange is remembered for her fieldwork for the federal Farm Security Administration among migrant workers and other dispossessed families during the Great Depression of the 1930s.[64] Decades after Lange's work, Highsmith photographed surviving shacks in the Weedpatch "Okie" camp in Kern County, California, that was the setting for much of John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath.[65]

"Two hundred years from now, people might want to study what types of screws were sold, and they will be able to study my images and find detail to understand how things have changed," Highsmith said in 2008 "These photos can tell a million and one stories. That's what sets still photography apart. With such tremendous quality, you can sit for hours and study a photo."[66]

Milestones[]

In 2007, the American Institute of Architects marked its 150th anniversary by inviting the public to vote on the AIA Web site for their favorite 150 U.S. architectural sites. Once the winners were selected—the Empire State Building finished first—the AIA used existing Highsmith photographs for more than 100 of the sites and commissioned her to photograph all but two of the remaining ones.[67] One of the two—New York's Penn Station, no longer stood, and the other, the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel on Hawaiʻi Island, had been badly damaged in an earthquake; historical photographs illustrated those sites. Enlargements of Highsmith's photos for the "AIA 150" appeared in an exhibit at the Institute's headquarters at the Octagon House in Washington, DC, and remain on the AIA 150 Web site.[68]

In April 2009, Highsmith was one of four women included in the Library of Congress's Women's History Month Profiles on its web site.[69]

Each year since 1999, Highsmith has photographed monumental federal buildings across the nation for a unit of the General Services Administration,[70] and has separately photographed art in federal buildings, including works commissioned by the Treasury Department and Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression of the 1930s.[71]

Highsmith has photographed several National Trust for Historic Preservation properties, including architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House in Illinois, Philip Johnson's Glass House in Connecticut, the Drayton Hall plantation house in South Carolina, and the Shadows-on-the-Teche manor home in Louisiana.[72]

For the Trust's Preservation Press in 1994, Highsmith and Landphair produced their first national book, America Restored, as well as a book on Washington's foreign embassies.[73] America Restored detailed two restoration projects in each state, including the extensive renovations of the Fordyce Bathhouse in Hot Springs, Arkansas; the Sheraton Palace Hotel in San Francisco; Rockwood Manor House in Wilmington, Delaware; Georgia's Jekyll Island Historic District; the covered bridges of Rush County, Indiana; Parlange Plantation in Louisiana; Broome County, New York's, carousels; and the Battleship Texas in Houston.[74]

On commission from the National Park Service, Highsmith photographed homes, personal belongings, and collections of four presidents (Lincoln, Eisenhower, Truman, and Theodore Roosevelt) as well as poet Carl Sandburg, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, Confederate commander Robert E. Lee, African-American businesswoman and teacher Maggie Walker, the pioneer American nurse, Clara Barton, and the Nez Perce American Indian Nation. The Park Service produced a "virtual multi-media exhibit" of Highsmith's presidential collection photographs.[75] In 2016 and 2017, Highsmith was the featured photographer in a Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History exhibit of national park images saluting the National Park Service's 100th anniversary.[76] In a story, "Renowned Photographer Captures America's Natural Treasures," the Voice of America displayed side-by-side photos of Highsmith's inspiration, photographic pioneer Frances Benjamin Johnston and Highsmith perched in the same location beneath a rock formation in Yellowstone National Park, a century apart. "'Do I not get that there are millions and billions of photographs being taken every day?'" Highsmith asked rhetorically," the VOA story quotes the photographer. "'I do. But unfortunately, most of those won't be around over time.'"[77]

In 2002 the U.S. Postal Service chose Highsmith's photograph of the Jefferson Memorial as the image for its new Priority Mail stamp.[78] Eleven years later, in 2013, the USPS selected another Highsmith image, a close-up, black-and-white image of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, for a new issue of its "second ounce," meaning 20-cent denomination, stamp. According to the postal service announcement, "In designing the stamp, art director Derry Noyes chose to work with a photograph of a sculpted portrait of Lincoln rather than a more traditional illustration or painting. Carol M. Highsmith's photograph of this iconic Lincoln statue offered a fresh take. Noyes selected a detail of the image in order to highlight the President's features most effectively."[79]

"America is ever changing and the people and places that shape our everyday lives must be captured to tell the important stories of our present and our past to future generations," Richard Moe, the president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, wrote. "I can't think of a better photographer to undertake [the] immensely important task of documenting America than Carol Highsmith."[80]

Getty Images/Alamy lawsuit[]

In July 2016, Highsmith instituted a $1.35 billion lawsuit against two stock photography organizations, Getty Images and Alamy, and their agents, over their attempts to assert copyright over, and charge fees for the use of, 18,755 of her images, after Getty sent her a bill for one of the images, which she used on her own website.[81][82][83] In November 2016, after the judge hearing the case dismissed much of Highsmith's case on grounds that she had relinquished her claim of copyright when she donated much of her work to the Library of Congress (and thus to the public domain), the remainder of the lawsuit was settled by the parties out of court.[84]

On August 18, 2016, Creative Commons, a nonprofit American organization that issues "public copyright licenses" enabling the free distribution of otherwise copyrighted work, said of the photographer on its website, "Highsmith's project predates our work as Creative Commons, but her work is very much in the spirit of our community. By removing copyright restrictions from her photographs, Highsmith is engaged in the important work of growing a robust commons built on gratitude and usability; her singular archive at the Library of Congress is a testament to one woman's passion and generosity."[85]

Annenberg Space for Photography Exhibit[]

In 2018, Carol M. Highsmith's work was featured in a six-month-long exhibition at the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles, California—assembled by American photography curator Anne Wilkes Tucker—showcasting images selected from more than 14 million visual items permanently housed at the Library of Congress. Of the 440 photographs in what was called "Not an Ostrich: and Other Images from America's Library," 48 were Highsmith's.[86] For a documentary movie that accompanied the exposition, a crew followed Highsmith "on the road" in Clarksdale, Mississippi and elsewhere a year earlier, in 2017.[87]

The exhibit's title was borrowed from a 1930 photograph in the national library's collection of a rare, fluffy-feathered goose held by an actress at a Madison Square Garden poultry show, thought to be taken by an unnamed photographer in the employ of the Underwood & Underwood Co. that produced stereograph views.[88]

In what the Annenberg museum described as "a captivating conversation," Highsmith was the featured speaker at an "Iris Nights" lecture series presentation, conducted by curator Tucker, of "the beauty, humor, and humanity of America." They discussed Highsmith's "decades-long project to photograph America with images from all 50 states. The conversation also covered her decision to donate all of her images from the project to the Library of Congress, her experiences 'on the road,' [she had just completed a study of Arizona and was headed to the states of Washington, Oregon, New York, and Rhode Island], and the influence of other trailblazing women photographers, such as Dorothea Lange and Frances Benjamin Johnston, both of whom have inspired Highsmith."[89]

In a review of the exhibit by the online LensCulture contemporary-photography magazine, Gena Williams wrote, "Juxtapositions are an important part of Not an Ostrich. One wall features Carol Highsmith's gleaming (and often scenic) images of Americana. 'Highsmith's view of America is a positive one. She has an eye for beauty,' [curator] Tucker says, comparing her work to photographers such as Ansel Adams."[90] The Lensculture review also published four of Highsmith's photographs, including one of a giant, lighted "MOM" artistic installation taken at the 2009 Burning Man "community and art" celebration in Black Rock Desert, Nevada.[90]

Commissions and awards[]

- Award of Excellence, Communications Arts Magazine, 1985[23]

- Pennsylvania Avenue Development Commission, 1987[16]

- Crescent Books Imprint, Random House Publishers, 36 books, 1997–2003[91]

- Photography of historic Federal buildings and art, for the General Services Administration, from 1999[70]

- Photography of presidential and other notables' belongings for the Museum Management Program of the National Park Service[92]

- Jefferson Memorial image chosen for first USPS Priority Mail stamp, 2002[93]

- Exclusive photographer of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) 150, America's Favorite Architecture, 2007[94]

- Library of Congress's Women's History Month Profile, (1 of 4 women profiled) 2008[30]

- General Services Administration Design Award, 2009[95]

- The Library of Congress featured Highsmith's "born-digital" America Collection ("born digital" refers to images originally produced by a digital camera, rather than those digitized from film) and shows her work on the Prints and Photographs website[32]

- In 2010, Highsmith photographed Alabama as the first state in her "21st Century America" project, funded by businessman George F. Landegger, whose family had operated pulp plants in the state. Landegger then donated funds to the Library of Congress for Highsmith to continue documentation of the American states.[96]

- In 2011, the Library of Congress acquired 6,500 images from Highsmith's film collection of her work in America that dates from 1980 to 2001. Most of the images are on 4" × 5" film. The film has been scanned and converted to high-resolution digital files.[32]

- During 2012 and 2013 Highsmith worked throughout California, visually documenting the entire state. The collection, known as the Jon B. Lovelace California Collection at the Library of Congress, was funded by the Capital Group, a California investment firm, in memory of Lovelace, who died in 2011.[57]

References[]

- ^ Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Online Catalog, accessed August 4, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Highsmith (Carol M.) Archive". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Q&A with Carol Highsmith". C-SPAN. May 24, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ Carter, Howard Williston (1994). Carter, a genealogy of the descendants of Thomas Carter of Reading and Weston, Mass., and of Hebron and Warren, Ct. Also some account of the descendants of his brothers, Eleazer, Daniel, Ebenezer and Ezra, sons of Thomas Carter and grandsons of Rev. Thomas Carter, first minister of Woburn, Massachusetts, 1642. Salem, Massachusetts: Higginson Book Co. ISBN 978-0-89459-212-6. OCLC 32899671.[page needed]

- ^ "Q&A Carol Highsmith, May 24 2011 - Video - C-SPAN.org". C-SPAN.org.

- ^ "Folk artist Bennie Carter (1st cousin of photographer Carol M. Highsmith) amid some of his creations outside his home, Rockingham County, North Carolina". 1980.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ http://cdn1.creativecirclemedia.com/ncpress/files/9eb554fc04.pdf[full citation needed]

- ^ Minnehaha Academy Arrow, Spring 2013, p. 26

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Carol Highsmith, on a 16-year quest to photograph America for the Library of Congress". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ http://library.gwu.edu/ead/ms2029.xml[verification needed]

- ^ Harden, Frank; Weaver, Jackson; Meyer, Ed (1983). On the radio with Harden and Weaver. Morrow. p. 82. OCLC 1150960882.

- ^ "Carol M. Highsmith: Photos and biography of Carol M. Highsmith, buy p…".

- ^ "Restoration work on the historic Willard Hotel in the 1980s, Washington, D.C." 1980.

- ^ (77 other Highsmith photos from this period at loc.gov

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Maya, Raquel (December 2007). "A Conversation with Carol Highsmith". Information Bulletin. 66 (12).

- ^ Clemetson, Lynette (January 4, 2006). "A Hotel Preens as the Center of Political Attentions". The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cole, Regina (Winter 1995). "Profile". Old House Interiors. 1 (4): 22–28.

- ^ "21st-Century America (October 2010) – Library of Congress Information Bulletin". loc.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Two Windows on the Willard: The Photographs of Carol M. Highsmith and Frances Benjamin Johnston". American Architectural Foundation. Archived from the original on September 7, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ^ Oldenburg, Don (August 25, 1987). "Doing what comes naturally". Washington Post.

- ^ "Who said, 'a little hard work never hurt anyone'". chacha.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Design Annual 26". Communication Arts. 27 (7): 6–7. November 1985. ASIN B00534M06A.

- ^ "This Is California". thisiscalifornia.us. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Through the Lens". Library of Congress Information Bulletin. 66 (12): 239. December 2007.

- ^ McCoy, Mary (July 23, 1992). "VISUAL ARTS" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- ^ "Carol M Highsmith". Fine Art America. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Les Krantz (1989). American photographers: an illustrated who's who among leading contemporary Americans. Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-1419-4.

- ^ "Highsmith (Carol M.) Archive – Background and Scope". www.loc.gov. February 3, 1980.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Women's History Month".

- ^ "This Is California". thisiscalifornia.us. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Carol M. Highsmith". outlookseries.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Photographer capturing San Diego for posterity". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "THIS IS ALABAMA". thisisalabama.us. Archived from the original on July 20, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Maya, Raquel. "A Photographic Gift to the Nation". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Wilkens, John (May 17, 2013). "Capturing San Diego for posterity". U-T San Diego. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "Saving America for posterity at the Library of Congress".

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Saving America for posterity at the Library of Congress", CBS News, 28 April 2013.

- ^ Urschel, Donna. "21st-Century America Photographer Carol Highsmith Documents a Nation". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith; Ted Landphair (January 1995). Forgotten No More: The Korean War Veterans Memorial story. Chelsea Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9620877-3-8.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith; Ted Landphair (June 1988). Union Station: A Decorative History of Washington's Grand Terminal. Chelsea Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9620877-0-7.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith; James L. Holton (January 1994). Reading Terminal and Market: Philadelphia's Gateway and Grand Convention Center. Chelsea Publishing. ISBN 978-0962087714.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith; Ted Landphair (August 1997). Colorado: A Photographic Tour story. Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0517186084. (and 14 additional "Photographic Tour" books published by Crescent).

- ^ "Highsmith (Carol M.) Archive: Selected Bibliography", Library of Congress.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith; Ted Landphair (February 10, 1998). Ireland: A Photographic Tour. Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-18757-9.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith (2001). World Trade Center: Tribute And Remembrance. Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-22092-4.

- ^ Dixie Legler; Carol M. Highsmith (2002). Historic Bridges of Maryland. Maryland Historical Trust Press. ISBN 978-0962087714.

- ^ Ryan Coonerty; Carol Highsmith (March 20, 2007). Etched in stone: enduring words from our nation's monuments. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-1-4262-0026-7.

- ^ Highsmith, Carol M.; Starr, Kevin (November 20, 2013). California Book: Carol M. Highsmith, Kevin Starr: 9780962087721: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-0962087721.

- ^ "The LOC.GOV Wise Guide : The Library Exposed". loc.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Meet the Woman Creating a Complete, Copyright-Free Visual Record of America".

- ^ dawn.kane@greensboro.com, Dawn DeCwikiel-Kane. "Photographer Carol Highsmith's work for Library of Congress is her calling".

- ^ Jerry Hayes (May 9, 2010). "Capturing Project Alabama in 100 days". WHNT19 News. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ "Search Results: "Washington D.C. Landegger" – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov.

- ^ "Search Results: "Connecticut" – Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov.

- ^ "The Picture Not Taken". ctexplored.org. September 29, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Library of Congress to Acquire California Images – News Releases (Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Money & Company". Los Angeles Times. November 17, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "California State Parks Prominent in Library of Congress Photo Exhibit Featuring Renowned Photographer Carol M. Highsmith" (PDF) (Press release). California Department of Parks and Recreation. April 16, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "Artepublishing :: Our Publications :: Great Photographs from the Library of Congress". artepublishing.com.

- ^ Kocher, Jen. "A picture of America".

- ^ "Library Announces Its First Online Conference for Educators".

- ^ "Photographs and papers of Frances Benjamin Johnston". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- ^ "Migrant Workers: Photographer: Dorothea Lange". Documenting America. Library of Congress. 1935.

- ^ "Dorothea Lange's "Migrant Mother" Photographs in the Farm Security Administration Collection: An Overview (Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Beth Rowen. "Renowned Photographer Plans a Cross-Country Trip to Photograph America: Carol M. Highsmith will donate her photos to the Library of Congress". Infoplease web site. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ "AIA Homepage – The American Institute of Architects". favoritearchitecture.org. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "America's Favorite Architecture". American Institute of Architects. 2007. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ "Carol M. Highsmith (b. 1946)". Women's History Month. The Library of Congress. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Historic Building Photographs". gsa.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Art in Architecture Program". gsa.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Carol M. Highsmith". carolhighsmith.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith; Ted Landphair (1992). Embassies of Washington. Preservation Press. ISBN 978-0-89133-170-4.

- ^ Carol M. Highsmith; Ted Landphair (1994). America restored. Preservation Press, National Trust for Historic Preservation. ISBN 978-0-89133-228-2.

- ^ "National Park Service – Museum Management Program". nps.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Taboh, Julie. "Renowned Photographer Captures America's National Treasures".

- ^ "3.85-dollar Jefferson Memorial". National Postal Museum. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ "2014 First Look: Abraham Lincoln Memorial Statue". uspsstamps.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "Carol M. Highsmith". carolhighsmithamerica.com. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Dunne, Carey (July 27, 2016). "Photographer Files $1 Billion Suit Against Getty for Licensing Her Public Domain Images". Hyper Allergic. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ Masnick, Mike. "Photographer Sues Getty Images For $1 Billion For Claiming Copyright On Photos She Donated To The Public". Techdirt. Retrieved July 28, 2016. includes a copy of the lawsuit

- ^ Text of Highsmith v Getty and others

- ^ "$1 Billion Getty Images Lawsuit Ends Not with a Bang, but a Whimper". November 22, 2016.

- ^ ""This is my time and I'm recording it": Carol Highsmith and the nature of giving – Creative Commons". August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Not an Ostrich: And Other Images from America's Library".

- ^ "Guitarist Bill Abel performs at the Hopson Plantation's converted commissary building, now a jazz venue and bar, on the outskirts of Clarksdale, in Mississippi's Delta region". 2017.

- ^ "Not an ostrich - but the oddly plumed "Floradora Goose" displayed at the poultry show a rare goose, decorated with fluffy un-gooselike feathers, being held by Miss Isla Bevan at the 41st annual Poultry Show at Madison Square Garden. It is called the Floradora Goose, and is a prizewinner". 1930.

- ^ "Carol M. Highsmith & Anne Wilkes Tucker: The Beauty, Humor, and Humanity of America".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams, Gena. "Rediscovering America with Anne Wilkes Tucker". LensCulture. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "Highsmith (Carol M.) Archive – Selected Bibliography". www.loc.gov. February 3, 1980.

- ^ "National Park Service – Museum Management Program". www.nps.gov.

- ^ "Arago: 3.85-dollar Jefferson Memorial". si.edu. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ Highsmith credit appears on 148 of 150 images; the other two were historical, black-and-white images; see "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "p. 9" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ^ "Highsmith Launches 21st-Century America Project – News Releases (Library of Congress)". loc.gov. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carol M. Highsmith. |

- Official website

- Carol M. Highsmith Collection at the Library of Congress

- This is America! Foundation Web site featuring Highsmith images of America

- Melissa Parker (July 15, 2010), Carol M. Highsmith Interview: Famed Photojournalist Documents America for the Library of Congress, Smashing Interviews

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Architectural photographers

- 1946 births

- Living people

- American women photographers

- Photographers from Minnesota

- Photographers from North Carolina

- Writers from Minnesota

- American University alumni

- University of Pennsylvania alumni

- People from Eden, North Carolina

- 20th-century American photographers

- 21st-century American photographers

- 20th-century American women artists

- 21st-century American women artists

- Thomas Carter family

- 20th-century women photographers

- 21st-century women photographers