Catholic Church in Poland

Catholic Church in Poland | |

|---|---|

| Polish: Kościół katolicki w Polsce | |

| |

| Type | National polity |

| Classification | Catholic |

| Orientation | Christianity |

| Scripture | Bible |

| Theology | Catholic theology |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Governance | KEP |

| Pope | Francis |

| Primate of Poland | Wojciech Polak |

| President | Stanisław Gądecki |

| Region | Poland |

| Language | Polish, Latin |

| Founder | Mieszko I |

| Origin | 966 Civitas Schinesghe |

| Separations | Polish-Catholic Church of Republic of Poland Protestantism in Poland |

| Members | 33 million |

| Official website | KEP |

Religion in Poland according to Statistics Poland 2015[1]

Religion in Poland according to Eurobarometer 2019[2]

The Polish Catholic Church, or Catholic Church in Poland, is part of the Roman Catholic Church under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome, and the Episcopal Conference of Poland. There are 41 Catholic dioceses of the Latin Church and two eparchies of the Eastern Churches in Poland. These comprise about 10,000 parishes and religious orders. There are 33 million registered Catholics[3][4]:4 (the data includes the number of infants baptized) in Poland.[5] The primate of the Church is Wojciech Polak, Archbishop of Gniezno. According to 2015 demographics, 92.9% of Poland's population is Roman Catholic.[3]

History[]

Ever since Poland officially adopted Latin Christianity in 966, the Catholic Church has played an important religious, cultural and political role in the country. Identifying oneself as Catholic distinguished Polish culture and nationality from neighbouring Germany, especially eastern and northern Germany, which is mostly Lutheran, and the countries to the east which are Orthodox. During times of foreign oppression, the Catholic Church was a cultural guard in the fight for independence and national survival. For instance, the Polish abbey in Częstochowa, which successfully resisted a siege in the Swedish invasion of Poland in the 17th century, became a symbol of national resistance to the occupation. The establishment of a communist regime controlled by the Soviet Union following World War II allowed the Church to continue fulfilling this role, although recent allegations suggest there was some minor collaboration between Polish clergy and the regime.[6]

The 1978 election of Polish Cardinal Karol Wojtyła as Pope John Paul II strengthened the ties of identification. John Paul's visits to Poland became rallying points for the faithful and galvanized opposition to the Soviet regime. His beatification in 2011 and canonization 3 years later further instilled pride and joy in the Polish people. In 2013, Pope Francis, John Paul II's 2nd successor (and who was made a cardinal by the Polish pope), announced that World Youth Day, the world's largest religious gathering of young people, would be held in Kraków, Poland in 2016.

In 2013 a succession of child sex abuse scandals within the Church, and the poor response by the Church, became a matter of some public concern.[7] The church resisted demands to pay compensation to victims.[8]

Number of Catholics in Poland[]

As of 2005 a majority of Poles, approximately 88%, identified themselves as Catholic, and 58% said they are active practicing Catholics, according to a survey by the Centre for Public Opinion Research.[9] According to the Ministry of Foreigns Affairs of the Republic of Poland, 95% of Poles belong to the Catholic Church;[10] this survey bases the number of adherents on the number of infants baptized,[5] as provided by the Catholic Church. The CIA Factbook gives a number of 87.2% belonging to the Catholic Church in 2012.[11] In the biggest part of Europe, the rates of religious observance have steadily decreased. However, Poland still remains one of the most devoutly religious countries in Europe. Polish Catholics participate in the sacraments more frequently than their counterparts in most Western European and North American countries. A 2009 study by the Church itself revealed that 80% of Poles go to confession at least once a year, while 60% of the respondents say they do so more often than once a year.[12] By contrast, a 2005 study by Georgetown University's Center for Applied Research on the Apostolate revealed that only 14% of American Catholics take part in the sacrament of penance once a year, with a mere 2% doing so more frequently.[13] Tarnów is the most religious city in Poland, and Łódź is the least. The southern and eastern parts of Poland are more active in their religious practices than those of the West and North. The majority of Poles continue to declare themselves Catholic.[14] This is in stark contrast to the otherwise similar neighboring Czech Republic, which is one of the least religious practicing areas on Earth, with only 19% declaring "they believe there is a God" of any kind.[15]

A 2014 survey conducted by the Church found that the number of Polish Catholics attending Sunday Mass had fallen by two million over the last decade, with 39% of baptized Catholics regularly attending Mass in 2014.[7][16] At the same time, however, this partly results from the fact that since 2004 2.1 million Poles have emigrated to Western Europe.[16] Writing for the Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny, Church sociologist Rev. Prof. Janusz Mariański has noted that these two million Polish emigrants are still listed in their parish records as members, so when Mass attendance is measured such emigres lower the official records.[17] The proportion of Mass attendees receiving Holy Communion is rising, while the number of Polish Catholic priests continues to rise as ordinations outpace deaths in Poland, though the number of nuns is decreasing.[16] The survey found that regular Sunday Mass attendance varies by dioceses from a high Diocese of Tarnów (69%) to a low Archdiocese of Szczecin-Kamień (24.3%), and reception of Holy Communion from 23.7% in the Tarnów diocese down to 10.4% in the diocese of Koszalin-Kołobrzeg.

Religious practice[]

The Centre for Public Opinion Research regularly conducts surveys on religious practice in Poland. A 2012 document reported that for more than a quarter-century church attendance and declarations of religious faith have been stable, decreasing only minimally since 2005 when the grief related to the death of Pope John Paul II led to an increase in religious practice among Poles. In a 2012 study, 42% of Poles declared that they attend religious services at least once a week, 18% do so once or twice a month, 32% do so several times a year, and only 8% do so never or almost never. Meanwhile, 94% of Poles consider themselves to be religious believers (9% of whom consider themselves "deeply religious"), while only 6% of Poles claim that they are non-believers.[18] According to the Church’s own sources,[4]:4 39.1% of Catholics required to attend the Sunday Mass, take part in it.

Easter continues to be an important holiday for Polish Catholics. According to a 2012 study by the CBOS (Centre for Public Opinion Research), 74% of Poles make an effort to participate in the sacrament of penance before Easter, 59% make an effort to attend the Stations of the Cross or Gorzkie żale (an increase of 6% since 2003), 57% want to improve themselves for the better (an increase of 7%), 49% want to help the needy (an increase of 8%), and 46% want to pray more (a decline of 5%).[19]

A CBOS opinion poll from April 2014 found the following:

| Lenten and Easter observances: Do you...? (CBOS 2014 poll)[20] | YES | NO |

|---|---|---|

| Fast on Good Friday | 83% | 17% |

| Go to Easter Confession | 70% | 30% |

| Have ashes put on your head on Ash Wednesday | 64% | 36% |

| Take part in the Easter Triduum celebrations | 56% | 44% |

| Take part in an Easter retreat | 53% | 47% |

| Take part in the Way of The Cross | 52% | 48% |

| Celebrate the Resurrection | 48% | 52% |

Apostasy[]

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (November 2020) |

During the October 2020 Polish protests, enquiries regarding the procedure for apostasy from the Polish Catholic Church became popular. Web search engine queries showed high frequencies for "apostasy" (Polish: apostazja) and "how to do apostasy" (Polish: jak dokonać apostazji), and a Facebook event titled "Quit the church at Christmas" was followed by 5000 people.[22]

As of 2020, the formal apostasy procedure in the Polish Catholic Church is a procedure defined on 7 October 2015 by the Episcopal Conference of Poland, which became effective as of 19 February 2016.[23][24] It can only be done in person, by delivering an application to a church parish priest. The procedure cannot be done by email, post, or state administrative services.[25] The procedure includes five elements:[24]

- a personal visit to the applicant's local parish church

- the applicant must be an adult

- three copies of an application form

- baptism certificate (original and copy)

- state identity card.

The chronological steps of the procedure are:[24]

- the applicant obtains his/her baptism certificate

- the applicant goes to his/her local parish office

- the applicant's identity is verified and the parish priest is obliged to try to convince the applicant to reverse his/her decision

- the applicant signs three copies of a formal act of defection; one copy is for the applicant

- the parish priest sends one of the acts to the curia; the curia orders the parish to make a notation of defection in the baptismal register

- the applicant returns to the parish office to obtain a baptismal certificate that includes the notation of "formal defection".

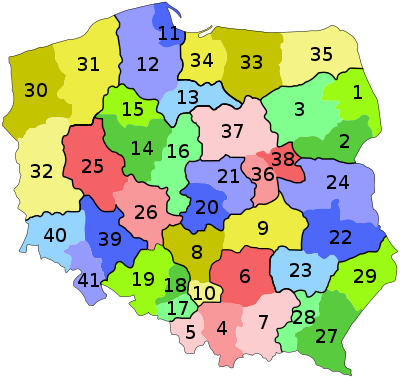

Latin territories[]

- Archdiocese

- Diocese

Latin names of dioceses in italics.

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church by country |

|---|

|

|

|

- Białystok, Bialostocensis (1)

- Drohiczyn, Drohiczinensis (2)

- Łomża, Lomzensis (3)

- Cracow, Cracoviensis (4)

- Bielsko–Żywiec, Bielscensis-Zyviecensis (5)

- Kielce, Kielcensis (6)

- Tarnów, Tarnoviensis (7)

- Częstochowa, Czestochoviensis (8)

- Radom, Radomensis (9)

- Sosnowiec, Sosnoviensis (10)

- Gdańsk, Gedanensis (11)

- Pelplin, Pelplinensis (12)

- Toruń, Thoruniensis (13)

- Gniezno, Gnesnensis (14)

- Bydgoszcz, Bydgostiensis (15)

- Włocławek, Vladislaviensis (16)

- Katowice, Katovicensis (17)

- Gliwice, Glivicensis (18)

- Opole, Opoliensis (19)

- Łódź, Lodziensis (20)

- Łowicz, Lovicensis (21)

- Lublin, Lublinensis (22)

- Sandomierz, Sandomiriensis (23)

- Siedlce, Siedlecensis (24)

- Poznań, Posnaniensis (25)

- Kalisz, Calissiensis (26)

- Przemyśl, Premisliensis (27)

- Rzeszów, Rzeszoviensis (28)

- Zamość-Lubaczów, Zamosciensis-Lubaczoviensis (29)

- Szczecin-Kamień, Sedinensis-Caminensis (30)

- Koszalin-Kołobrzeg, Coslinensis-Colubreganus (31)

- Zielona Góra-Gorzów Wielkopolski, Viridimontanensis-Gorzoviensis (32)

- Warmia (Olsztyn), Varmiensis (33)

- Warsaw, Varsaviensis (36)

- Płock, Plocensis (37)

- Warsaw-Praga, Varsaviensis-Pragensis (38)

- Wrocław, Vratislaviensis (39)

- Legnica, Legnicensis (40)

- Świdnica, Suidniciensis (41)

Ukrainian Greek Catholic territory[]

- Archeparchy

- Eparchies

- Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Przemyśl–Warsaw

Extraterritorial units[]

- Military Ordinariate of Polish Army

Finance[]

A concordat between the state and the Church allows the teaching of religious education in school.[26] There are 31,000 state-paid religious education teachers.[27] The government partially subsidises the Church for Catholic schools, historic Church buildings, and salaries for public and private religious teachers. This totals about 2 billion zł (~ US$633 million on 5 V 2013).[28]

According to Cardinal Kazimierz Nycz, money from money given by people including voluntary and semi-mandatory (e.g. required during marriages[citation needed]), religious events and other, is more than 6 billion zł(~ US$1.9 billion on 5 V 2013[clarification needed]).[28]

See also[]

- The Most Holy Virgin Mary, Queen of Poland

- List of saints of Poland

- Religion in Poland

- Religious denominations in Poland

- List of Catholic dioceses in Poland

- List of Polish cardinals

- October 2020 Polish protests

- Reorganization of occupied dioceses during World War II

- Nazi persecution of the Catholic Church in Poland

- Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

References[]

- ^ GUS. "Infographic - Religiousness of Polish inhabitiants". stat.gov.pl. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Special Eurobarometer 493, European Union: European Commission, September 2019, pages 229-230". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland (2014)" (PDF). stat.gov.pl.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia AD 2017" (PDF). Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae in Polonia (in Polish). Instytut Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego SAC. 2017 (2017). 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kościół podaje 7% ochrzczonych z kapelusza! | Www.wystap.pl – jak wystąpić z kościoła. Centrum informacji i platforma batalii". Wystap.pl. 22 August 2010.

- ^ Smith, Craig S. (10 January 2007). "In Poland, New Wave of Charges Against Clerics". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Matthew Day (11 July 2014). "Polish Catholics in decline". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Jan Cienski (11 October 2013). "Polish Catholic Church rocked by sex abuse scandal". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ (in Polish) Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej (Centre for Public Opinion Research (Poland) CBOS). Komunikat z badań; Warszawa, Marzec 2005. Co łączy Polaków z parafią? Preface. Accessed 2007-12-14.

- ^ "Churches and Religious Life in Poland". poland.gov.pl.

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook". CIA. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "80% Polaków chodzi do spowiedzi – Wiadomości – WP.PL". Wiadomosci.wp.pl. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ "A Comeback for Confession". Time. 27 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007.

- ^ "Liczenie wiernych w kościołach". Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ "Social values, Science and Technology" (PDF). Eurobarometer. June 2005. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Sunday Mass attendance falls below 40% in Poland". CatholicCulture.org. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ "Dwa miliony wiernych nie odeszło z kościoła - raczej wyemigrowało". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "CBOS potwierdza. Zdecydowana większość Polaków uznaje się za katolików". . April 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ "CBOS: Polak może nie chodzić do Kościoła, ale jajkiem się podzieli". Wprost. April 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Małgorzata Omyła-Rudzka (April 2014). "PRAKTYKI WIELKOPOSTNE I WIELKANOCNE POLAKÓW" (PDF) (in Polish). CBOS. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Mirosława Grabowska (December 2013). "RELIGIA I KOŚCIÓŁ W PRZESTRZENI PUBLICZNEJ" (PDF) (in Polish). CBOS. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ "Apostazja - czym jest i jak wiele osób dokonuje jej w Polsce?" [Apostasy - what it is and how many people do it in Poland?]. Polsat news (in Polish). 26 October 2020. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Stanisław, Gądecki; Miziński, Artur G. (7 October 2015). "Dekretu Ogólnego Konferencji Episkopatu Polski w sprawie wystąpień z Kościoła oraz powrotu do wspólnoty Kościoła" [General Decree of the Episcopal Conference of Poland regarding quitting the Church and returning to the Church community] (PDF). Episcopal Conference of Poland (in Polish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Procedura wystąpienia z Kościoła" [Procedure for quitting the Church]. Apostazja Info (in Polish). 2020. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Chabasiński, Rafał (25 October 2020). "Procedura apostazji – jak wystąpić z Kościoła?" [The apostasy procedure - who can you quit the Church?]. bezprawnik (in Polish). Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Concordat Watch - Poland - Polish concordat (1993) : Text and criticism". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ "Notanant on Notanant: - Login page". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Polska, Grupa Wirtualna (4 May 2013). "Kościół zdradza, ile polscy wierni dają na tacę". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

Further reading[]

- Frucht, Richard. Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. Volume 1. ABD-CLIO inc. Santa Barbara, Ca.

- Pease, Neal (Autumn 1991). "Poland and the Holy See, 1918–1939". Slavic Review. Slavic Review, Vol. 50, No. 3. 50 (3): 521–530. doi:10.2307/2499849. JSTOR 2499849.

- Weinbaum, Laurence (Fall 2002). "Penitence and Prejudice: The Roman Catholic Church and Jedwabne". Jewish Political Studies Review. 14 (3–4).

External links[]

- Conference of the Episcopate of Poland (in Polish)

- Apostasy in Poland

- Procedura apostazji: poradnik i wzór oświadczenia (in Polish)

- Apostazja.info - Jak wypisać się z Kościoła katolickiego (in Polish)

- Home (in Polish)

- Apostazja – instrukcja krok po kroku i wzory dokumentów (in Polish)

- Catholic Church in Poland

- Catholic Church by country

- Catholic Church in Europe

- Polish culture