Cecil Williams (pastor)

Cecil Williams | |

|---|---|

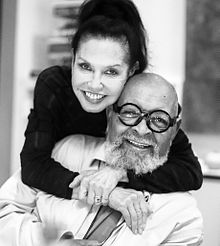

Williams and his wife Janice Mirikitani | |

| Born | Albert Cecil Williams September 22, 1929 San Angelo, Texas, U.S. |

| Education | B.A. (Sociology), Huston–Tillotson University (1952) ThM, Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University (1955) |

| Occupation | Evangelist, activist, community leader, author |

| Spouse(s) | Evelyn Robinson, 1956–1976 (divorced) Janice Mirikitani, 1982–2021 |

| Children | 2 with Robinson |

Albert Cecil Williams (born September 22, 1929) is an American pastor, community leader, and author who is the pastor emeritus of Glide Memorial United Methodist Church.

Early life[]

One of six children, Williams was born in San Angelo, Texas to Earl Williams Sr.[1][2] He had four brothers, Earl Jr., Reedy, Claudius "Dusty", Jack and a sister, Johnny.[1] He received a Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology from Huston–Tillotson University in 1952.[3] He was one of the first five African American graduates of the Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in 1955.[4] He became the pastor of Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco, California in 1963, and founded the Council on Religion and the Homosexual the following year.[2] He welcomed everyone to participate in services and hosted political rallies in which Angela Davis and the Black Panthers spoke and lectures by personalities as diverse as Bill Cosby and Billy Graham.[2] When Patty Hearst was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, Williams attempted to negotiate a deal for her release.[2]

In 1967, Williams had the cross removed from the church's sanctuary, saying it was a symbol of death and that his congregation should instead celebrate life and living. "We must all be the cross," he explained.[5]

LGBT rights activism[]

Drawing on his experiences in the civil rights movement, Williams was one of the first African-Americans to become involved in the gay rights movement. In 1964, he gave a speech at the Society for Individual Rights in San Francisco, which was more outspoken than the contemporary Mattachine Society. Based on the contemporary campaign for African-American voting rights, he suggested that gays should use their votes to gain political power and effect change. In his advice for gay movement to create tensions, he echoed Martin Luther King Jr.'s Letter from Birmingham Jail:[6]

I think that we must not be afraid of controversy or tension. We in the civil rights movement have learned how to rock the boat, how to disturb complacent middle-class people, how to root out complacency. It is good to have strong disagreement because from it comes movement and reaction. Controversy is the need; it stimulates communication and the exchange of ideas. Rejection once in awhile is a good thing too. It forces one to find oneself . . . Tension leads to resolution, to movement; at least, it lets people know that a living, fulfilling movement is on its way.

Legacy[]

Under his leadership, Glide Memorial became a 10,000-member congregation of all races, ages, genders, ethnicities, sexual orientations, and religions. It is the largest provider of social services in the city, serving over three thousand meals a day, providing AIDS/HIV screenings, offering adult education programs, and giving assistance to women dealing with homelessness, domestic violence, substance abuse, and mental health issues.[2] In January 1977 Williams handed out the Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award to Rev. Jim Jones. On November 18, 1978, Jones led nearly 900 of his followers to commit suicide at their cult compound in Jonestown, Guyana.

Williams retired as pastor in 2000 having turned 70 years old, the mandatory age of retirement for pastors employed by the United Methodist Church.[7] (Pastors in the United Methodist Church are not employed by the local church or congregation. Instead, UMC pastors are assigned to a local church by the presiding bishops of the global Church.) When Williams became ineligible for assignment to a congregation by the episcopate, the local congregation and affiliated non-profit foundation hired Williams to fill a new office entitled Minister of Liberation. The position was created to allow Williams to officially continue to serve the community and church.[citation needed]

In August 2013, the intersection of Ellis and Taylor Streets (location of the Glide church in San Francisco) was renamed "Rev. Cecil Williams Way" in honor of Williams.[8]

Both Williams and the church are featured in the 2006 film The Pursuit of Happyness.[9]

Personal life[]

Williams was married to school teacher Evelyn Robinson (1928–1981) from 1956 until their divorce in 1976.[1] They had two children, a son, Albert and a daughter, Kim.[1][3] He was married to Janice Mirikitani, a poet, from 1982 until her death in 2021.[3] He is the author of I'm Alive: An Autobiography,[10] published in 1980, and he collaborated with Mirikitani on the book Beyond the Possible,[11] published in 2013.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Rev. Cecil Williams". NNDB.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Cecil Williams". pbs.org. The Faith Project. 2003. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Strasburg, Jenny (October 17, 2004). "At a Crossroads / Assuming Cecil Williams can let go, what will become of Glide Memorial?". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ "SMU Marks 50th Anniversary Of First African-American Graduates" (Press release). Southern Methodist University. May 12, 2005. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ Williams, Cecil; Laird, Rebecca (1992). No Hiding Place: Empowerment and Recovery for Our Troubled Communities. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 9780062509673.

- ^ Long, Michael G. (2012). Martin Luther King Jr., Homosexuality, and the Early Gay Rights Movement: Keeping the Dream Straight?. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-1-137-27551-6.

- ^ Gilbert, Kathy L. (2004). "Delegates retain mandatory retirement age rules". United Methodist Church. umc.org. Note: By 2013, retirement age had been changed to 72. See Hahn, Heather (2013). Conference withdraws clergy age guidelines. umc.org. See also Mathison, John Ed (2016). "Retirement or Transition". johnedmathison.org.

- ^ Padojino, Jamey (August 20, 2013). "Tenderloin Corner Named To Honor Glide Co-Founder". The San Francisco Appeal.

- ^ Black, Nathan (December 18, 2006). "'Pursuit of Happyness' Tops Box Office, Highlights Church". Christian Post.

- ^ Williams, Cecil (1980). I'm Alive: An Autobiography. San Francisco: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-250950-5.

- ^ Williams, Cecil; Mirikitani, Janice (2013). Beyond the Possible: 50 Years of Creating Radical Change in a Community Called Glide. New York: HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-210505-9.

- People from San Angelo, Texas

- African-American Methodist clergy

- American Methodist clergy

- Huston–Tillotson University alumni

- Perkins School of Theology alumni

- 1929 births

- Living people

- Religious leaders from the San Francisco Bay Area

- American United Methodist clergy

- LGBT rights activists from the United States