Chakana

The chakana (or Inca Cross) is a stepped cross made up of an equal-armed cross indicating the cardinal points of the compass and a superimposed square. The square is suggested to represent the other two levels of existence. The three levels of existence are Hana Pacha (the upper world inhabited by the superior gods), Kay Pacha, (the world of our everyday existence) and Ukhu or Urin Pacha (the underworld inhabited by spirits of the dead, the ancestors, their overlords and various deities having close contact to the Earth plane). The hole through the centre of the cross is the Axis by means of which the shaman transits the cosmic vault to the other levels. It is also said to represent Cusco, the center of the Incan empire, and the Southern Cross constellation.

Composition[]

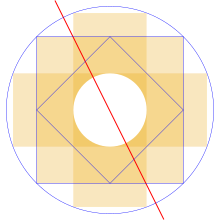

The geometry of the symbol has a high degree of symmetry. The symbol can be drawn from a circle. A square is inscribed in the circle, with the corners tangent to the circle. This forms the "middle step" of the ladder. A smaller square (tilted 45 degrees) is made from the midpoints of the large square. Connecting the midpoints of the small square and extending the lines to the edge of the circle will form the arms of the cross, otherwise known as the "first" and "last" steps of the chakana. Lines are drawn from the points the lines exit the circle, to complete the cross. A small circle is made from the diameter of the cross lines. To proof the construction, a separate construction line is drawn from the point where the square corners with the cross rectangles to the same point on the opposite side. If the line is 27 degrees from the vertical, the chakana is properly drawn.

Historical evidence[]

The chakana is one of the oldest symbols in the Andes. It appears as a prominent element of the decoration of the Tello Obelisk, a decorated monolithic pillar discovered by Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello at the Chavín culture site of Chavín de Huántar. Construction of Chavín de Huántar began around 1200 BCE and the site continued in use to about 400 BCE. The exact date of the Tello Obelisk is not known, but based on its style it probably dates to the middle of this range, around 800 BCE. The form of the chakana may be replicated in the Akapana, a large terraced platform mound with a central reservoir built at the site of Tiahuanaco by people of the Tiwanaku culture near Lake Titicaca, Bolivia and dating to about AD 400. Tiwanaku was the center of the Tiwanaku Empire, which thrived in the southern Andes from about 400 to 1000 CE.

The mestee historian Garcilaso de la Vega, el Ynga, reports about a holy cross of white and red marble or jasper, which was venerated in 16th-century Cusco[citation needed].[1] The cross had been kept in a royal house, in a sacred place or wak'a, but the Incas did not worship it. They simply admired it because of its beauty. The cross was square (quadrada), measuring about two by two feet, its branches three inch wide, the edges carefully squared and the surface brightly polished.[citation needed][2]

The Incas began to venerate the holy cross, after they heard how Pedro de Candia had miraculously defied a lion and a tiger holding a cross. When the Spaniards captured the city, they transferred the cross to sacristy of the newly built cathedral, where De la Vega saw it in 1560. He was surprised that the clergy had not decorated it with gold or gems.[3] As we know from Middle America, this may have been part of a deliberate strategy by mendicant friars, trying to adapt to indigenous cultural codes. As a rule, the veneration of the holy cross was a carefully designed ecclesiastical enterprise, incorporating native symbols and reproducing them on sacral level. Most surviving Andean crosses do not predate the 16th century.[4] Ongoing stories about indigenous crosses contributed to the idea of a 'natural' religion that would have prepared the Indians for their inevitable conversion to Christianity.[5]

Controversy[]

Some scholars regard it as an “invented tradition".[6] Although the Chakana as the 'Andean cross', presented as an Inca and pre-Inca symbol bearing cultural, spiritual, or mystical interpretations as expressed in this article, has wide popularity in contemporary Andean culture, its roots are no older than the late 20th century, and the popular version, than 2003. The current Chakana mythos as it impacts the New Age belief system and the Peruvian tourist-oriented economy initiates from the 2003 publication of the book Andean Awakening,[7] authored by Jorge Luis Delgado, and Mary Anne Male. This is the source of the myth[verification needed]. They are followed by such authors as Mark Torra and Roger Calverley (CHAKANA: Secret Teachings of an Ancient Andean Mystery School).[8] The archaeoastronomer Carlos Milla Villena published his own, distinctly different speculative interpretations of the chacana as “andean, cross” in Génesis de la cultura andina,1983.[9]

Mainstream scientific, scholastic, and archaeological sources do not refer to or support the word chakana as the cross-and-box design - rather, it is in Runasimi,[10] the traditional language of the Inca peoples, (modern Quechua), derived from chaka, 'bridge', and means 'to cross over', or 'a crossing'.[11] Among chroniclers such as the Jesuit missionary and naturalist José de Acosta, 1590,[12] it is applied to the group of stars commonly identified as the Belt of Orion.[13] The chroniclers do not refer to the chakana, or chacana, as the “andean cross,” or as reflecting a symbolical or semiotic tradition.

The twelve-cornered design itself occasionally appears in pre-contact artifacts such as textiles and ceramics from such cultures as the Wari, Ica, and Tiwanaku, but with no particular emphasis and no key or guide to a means of interpretation.[14]

See also[]

Further reading[]

- Soledad Cachuan: Mitología Inca, Buenos Aires 2008

- Drury: The Elements of Shamanism, Element Books, 1989.

- Mariano Cueva: Historia de la iglesia en Mexico, vol. 1, Mexico 1928, pp. 82–86

- Wilbert Escobedo Araoz: La cruz cuadrada andina, chacana, [Cusco 2011] (alternative) (the historical account draws largely, without mentioning, on Cueva, 1928).

- Javier Lajo, Filosofía indígena inka: la Tawachakana

References[]

- ^ Horner, Channing (2020-08-26). "Comentarios reales de los Incas, Book 2, Chapter 3".

- ^ Horner, Channing (2020-08-26). Book 2, Chapter 3 "Comentarios reales de los Incas, Book 2, Chapter 3" Check

|url=value (help). - ^ Garcillago de la Vega, First part of the Royal Commentaries of the Yncas, 1869, repr. Cambridge 2010, vol. 1, p. 122

- ^ Mónica Domínguez Torres, Military Ethos and Visual Culture in Post-Conquest Mexico, Burlington 2013, pp. 61-110

- ^ Simon Ditchfield, ‘What Did Natural History Have to Do with Salvation? José de Acosta SJ (1540-1600) in the America's', in: Peter Clarke and Tony Claydon, God's Bounty? The Churches and the Natural World, Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY 2010, pp. 144-168

- ^ Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger, ed. (1983). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521246458.

- ^ MaryAnn Male Jorge Luis Delgado (Author). Andean Awakening Publisher: Council Oak Books: MaryAnn Male Jorge Luis Delgado: Amazon.com: Books. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ^ CHAKANA: Secret Teachings of an Ancient Andean Mystery School eBook: Roger Calverley: Kindle Store. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ^ Villena, Carlos Milla (2008-09-04). "Génesis de la cultura andina - Carlos Milla Villena - Google Libros". Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ^ "Runa Simi pantachiqkunamanta – About the Forgers of Runa Simi | CLACS @ NYU". Clacsnyublog.com. 8 March 2011. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ^ "At the Crossroads of the Earth and the Sky: An Andean Cosmology (Latin American Monographs: No. 55) - Kindle edition by Gary Urton. Politics & Social Sciences Kindle eBooks @". Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ^ Joseph Acosta, Historia natural y moral de las Indias, Sevilla 1590, p. 310

- ^ "startab2". Astronomy.pomona.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-09-23. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

- ^ "Images". tocapu.org. Retrieved 2016-12-24.

External links[]

- Inca mythology

- Symbols

- New Age