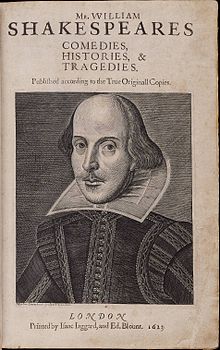

Chandos portrait

| The Chandos Portrait of William Shakespeare | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Attributed to John Taylor |

| Year | c. 1600s |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 55.2 cm × 43.8 cm (21+3⁄4 in × 17+1⁄4 in) |

| Location | National Portrait Gallery, London |

| Accession | NPG 1 |

The Chandos portrait is the most famous of the portraits that are believed to depict William Shakespeare (1564–1616). Painted between 1600 and 1610, it may have served as the basis for the engraved portrait of Shakespeare used in the First Folio in 1623.[1] It is named after the Dukes of Chandos, who formerly owned the painting. The portrait was given to the National Portrait Gallery, London on its foundation in 1856, and it is listed as the first work in its collection.[2]

It has not been possible to determine with certainty who painted the portrait, or whether it really depicts Shakespeare. However, the National Portrait Gallery believes that it probably does depict the writer.

Authorship and provenance[]

It has been claimed that Shakespeare's friend Richard Burbage (1567–1619) painted the Chandos portrait,[3] but the first known reference to the painting is in a note written in 1719 by George Vertue, who states that it was painted by John Taylor, a respected member of the Painter-Stainers' company who may also have been the same John Taylor who acted with the Children of Paul's.[4] Vertue refers to Taylor as an actor and painter and as Shakespeare's "intimate friend". Katherine Duncan-Jones argues that 'John Taylor' could have been a misreading of what had originally been "Jo: Taylor"; she suggests that this may refer to the actor Joseph Taylor, who was a protégé of the older Shakespeare.[5]

Vertue also states that before the Duke of Chandos acquired it, the portrait was owned by Shakespeare's possible godson, William Davenant (1606–1668),[3][4] who, according to the gossip chronicler John Aubrey, claimed to be the playwright's illegitimate son.[6] He also states that it was left to Davenant in Taylor's will and that it was bought by Thomas Betterton from Davenant and then sold to the lawyer Robert Keck, a collector of Shakespeare memorabilia.[2][3]

After Keck's death in 1719, it passed to his daughter, and was inherited by John Nichol, who married into the Keck family. Nichol's daughter Margaret married James Brydges, 3rd Duke of Chandos. The painting passed through descent within the Chandos title until Richard Temple-Grenville, 2nd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos sold it to the Earl of Ellesmere in 1848. Ellesmere donated it to the National Portrait Gallery.[7]

Scholarly views[]

A contemporary image of the playwright is the engraving in the posthumously published First Folio of 1623, which was created by Martin Droeshout and was probably commissioned by Shakespeare's friends and family. It is considered likely that the Droeshout engraving is a reasonably accurate likeness of the bard because of its acceptance by these close associates and that contemporaries such as Ben Jonson praised it at the time of the publication.[8] Since the man in the Chandos portrait resembles the one in the Droeshout engraving, the similarity lends an indirect legitimacy to the oil painting. A further indication of legitimacy is the fact that the Chandos portrait was the inspiration for two posthumous portraits of Shakespeare, one by Gerard Soest and another, grander one, known as the "Chesterfield portrait" after a former owner of that painting.[2] These were probably painted in the 1660s or 1670s, within living memory of Shakespeare. The Chesterfield portrait is held by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon.

In 2006, art historian Tarnya Cooper of the National Portrait Gallery completed a three-and-a-half-year study of portraits purported to be of Shakespeare and concluded that the Chandos portrait was most likely a representation of Shakespeare. Cooper points to the earring and the loose shirt-ties of the sitter, which were emblematic of poets (the poet John Donne and Shakespeare's patron the Earl of Pembroke sported similar fashions). However, she readily acknowledges that the painting's authenticity cannot be proven.[2][9]

Cooper also notes that the painting has been badly damaged by over-cleaning and retouching. Parts are abraded and some parts have been slightly altered. The hair has been extended and the beard is longer and more pointed than when originally painted.

Copies[]

In addition to the Chesterfield portrait, a copy was made at least as early as 1689, by an unknown artist. Many 18th century images used it as a model for portrayals of Shakespeare.

The painting was engraved by Gerard Vandergucht for Nicholas Rowe's 1709 edition of Shakespeare's works. Another print was made by Jacobus Houbraken in 1747.[2]

Ethnic interpretations[]

Because the images of Shakespeare are either doubtful in provenance or lacking expression, no one image seems to reconcile well with readers' imaginations. The relatively dusky features have caused repeated comment. George Steevens said that the picture gave Shakespeare "the complexion of a Jew, or rather that of a chimney sweeper in the jaundice".[10] According to Ben Macintyre, "Some Victorians recoiled at the idea that the Chandos portrait represented Shakespeare. One critic, J. Hain Friswell, insisted 'one cannot readily imagine our essentially English Shakespeare to have been a dark, heavy man, with a foreign expression'."[11] Friswell agreed with Steevens that the portrait had "a decidedly Jewish physiognomy" adding that it displayed "a somewhat lubricious mouth, red-edged eyes" and "wanton lips, with a coarse expression."[12] According to Ernest Jones, the portrait convinced Sigmund Freud that Shakespeare was French: "He insisted that his countenance could not be that of an Anglo-Saxon but must be French, and he suggested that the name was a corruption of Jacques Pierre."[13]

References[]

- ^ "National Portrait Gallery – Portrait NPG 1; William Shakespeare". London: National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Tarnya Cooper (ed), Searching for Shakespeare, National Portrait Gallery and Yale Center for British Art, Yale University Press, 2006, pp. 54–61

- ^ a b c Mary Edmond, "The Chandos Portrait: A Suggested Painter", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 124, No. 948, March 1982, pp. 146-147+149.

- ^ a b Cooper et al., 54.

- ^ Katherine Duncan-Jones, "A precious memento: The Chandos Portrait and Shakespeare's 'intimate friend'", Times Literary Supplement, April 25, 2014, pp.13–15.

- ^ Powell, Anthony (2005). Some Poets, Artists & "A Reference for Mellors". Timewell Press. p. 30. ISBN 1-85725-210-1.

- ^ Werner Habicht, David John Palmer, Roger Pringle, Images of Shakespeare: Proceedings of the Third Congress of the International Shakespeare Association, 1986, International Shakespeare Association Congress, University of Delaware Press, 1986, p.27

- ^ Cooper, Tarnya; Pointon, Marcia; Shapiro, James; Wells, Stanley (2006). Searching for Shakespeare. Yale University Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-300-11611-X.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (2 March 2006). "The only true painting of Shakespeare – probably". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ^ Schoenbaum, Samuel, Shakespeare's Lives, Oxford University Press, 1991, p.205.

- ^ Sunday Times (of London) article by Ben Macintyre, 10 March 2009, "Commentary: Portrait alleged to be the face of William Shakespeare" http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/visual_arts/article5877544.ece

- ^ Louis Marder, His Exits and His Entrances: The Story of Shakespeare's Reputation, Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1963, p.203

- ^ Ernest Jones, The life and work of Sigmund Freud, Basic Books, vol.1 1961 p.18.

External links[]

- Portraits of William Shakespeare

- English paintings

- Portraits by British artists

- 16th-century portraits

- 17th-century portraits

- Paintings in the National Portrait Gallery, London