Cheam

| Cheam | |

|---|---|

Top to bottom, left to right: Grade II listed Nonsuch Mansion in Nonsuch Park; The Old Rectory, Cheam; Whitehall during Cheam Charter Fair; Nonsuch Park | |

Cheam Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 10,285 (2011 Census. Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ245625 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | SUTTON |

| Postcode district | SM2, SM3 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Cheam (/ˈtʃiːm/) is a suburb now in the London Borough of Sutton, England, 10.9 miles (17.5 km) south-west of Charing Cross. It divides into North Cheam, Cheam Village and South Cheam. Cheam Village contains the listed buildings Lumley Chapel and the 16th-century Whitehall. It is adjacent to two large parks, Nonsuch Park and Cheam Park. Nonsuch Park contains the listed Nonsuch Mansion. Parts of Cheam Park and Cheam Village are in a conservation area. Cheam is bordered by Worcester Park to the north-west, Morden to the north-east, Sutton to the east, Ewell to the west and Banstead and Belmont to the south.

History[]

The Roman road of Stane Street forms part of the boundary of Cheam. The modern London Road at North Cheam follows the course of the Roman road through the area. It is designated A24.

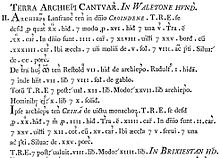

The village lay within the Anglo-Saxon administrative division of Wallington hundred.[2] Cheam is mentioned in the Charters of Chertsey Abbey in 727, which mentions Cheam being given to the monastery of Chertsey in 675; the name appears as Cegeham.[3] However, the Charters are of dubious origin and are now regarded as obvious fabrications.[4][2] The name 'Cheam', based on Cegeham, may mean 'village or homestead by the tree-stumps'.[5]

Cheam appears in Domesday Book as Ceiham. Held by Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury, its Domesday assets were four hides, one church, 17 ploughs, 1 mile (1.6 km) of meadow, and woodland worth 25 hogs. It rendered £14.[6]

In the Middle Ages, Cheam had potteries,[7] and recent excavations have been carried out by archaeologists.[8] In 1259, Henry III of England made Cheam a town by charter. In 1538, part of Cheam was handed over to Henry VIII. The same year, Henry began work on Nonsuch Palace, which he decorated elaborately. This was later sold and demolished.

In 1801, the time of the first census, Cheam had a population of 616 Cheamonians. Records of Cheam Charter Fair date back to the 1800s, when a fairground accompanied the market.[9][10][11]

Cheam was the original home of Cheam School which was formed in Whitehall in 1645 and later occupied Tabor Court from 1719 until 1934 when the school moved to Berkshire. Prince Philip attended the school in Cheam in the years immediately preceding its move.

Cheam Charter Fair[]

Every year on 15 May the Cheam Charter Fair is held. It is thought to date back to 1259 when Henry III granted Cheam a charter, making it a town. Firm historical records of Cheam Charter Fair date back to the 1800s when a fairground accompanied the market.

Cheam Village and North Cheam[]

Cheam Village is centred on the crossroads between Sutton, North Cheam, South Cheam and Ewell. As well as bus services, it is served by Cheam mainline station which is in London Travelcard Zone 5 and one stop from Sutton, about 1 mile (1.6 km) away, and two from Epsom, about 3 miles (4.8 km) away. Services from Cheam to central London include direct trains to Victoria which take about 30 minutes.

It has a conservation area[12] and a number of historic buildings dating back several centuries, including Nonsuch Mansion, the gabled Whitehall and Lumley Chapel, and a Georgian former rectory.[13]

Cheam Village is a part of Cheam. Cheam Village Conservation Area was designated in 1970 – it covers historic parkland, housing of varying styles and age and a mock Tudor shopping area with timber detailing and leaded-lights.[14] The entrances to Cheam Park and Nonsuch Park with its historic mansion are approximately two hundred yards from the village centre crossroads.

North Cheam is centred 1 mile (1.6 km) north, at the crossroads between Cheam Village and Worcester Park, Epsom and Morden. There are established bus routes serving the area, including services 213 (Sutton to Kingston), 151 (Wallington to Worcester Park), 93 (North Cheam to Putney Bridge) and the less frequent X26 express service between Heathrow Airport and Croydon.

Victoria Junction is the centre of North Cheam. The area consists of a large Sainsbury's supermarket with adjoining Starbucks, a neighbouring park, a number of independent shops and restaurants, a post office and a Costa. There are plans to redevelop the site of a vacant 1960s building at the North Cheam crossroad and expand commercial and residential buildings.

St. Anthony's Hospital is a large private hospital in North Cheam.

Cheam Leisure Centre, on Malden Road, has facilities including a swimming pool (30m x 12m), squash courts and fitness gym.

The population of Cheam, consisting of the Cheam and Nonsuch wards, was 20,972 in 2011.

Places of note[]

Whitehall[]

Whitehall is a timber framed and weatherboarded house in the centre of Cheam Village. It was originally built in about 1500 as a wattle and daub yeoman farmer's house but has been much extended. The external weatherboard dates from the 18th century. In the garden there is a medieval well which served an earlier building on the site.

Now an historic house museum, the building features a period kitchen, and house details from the Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian eras. The museum temporarily closed in 2016 to allow for a £1.6m refurbishment of the building. It reopened in June 2018 with improved facilities.[15]

Cheam War Memorial[]

Close to Cheam Library and the much-rebuilt Church, the memorial is to the people of Cheam who lost their lives during World War I, World War II and the Falklands War.

There are a number of inscriptions on the structure, including one at the 12 O'Clock Face which reads:

Our Glorious Dead / Their names shall endure for evermore.[16]

It was designated a Grade II listed building by English Heritage in December 2016.[17]

The Old Rectory[]

The Old Rectory is a large part timber-framed house, built in the Tudor period, but extended and remodelled in the 18th century. It is occasionally open to the public.

The Old Cottage[]

The Old Cottage was built in the late 15th or early 16th century. Initially built as a cottage, it became a small brewery in the 18th century. It originally stood in the Broadway (then Malden Road) near the junction with Ewell Road. Under threat of demolition when the road was widened in 1922, it was saved by the local council, working with a local architect and historian.

The building was dismantled by removing the original wooden pins from the timber frame. The parts were then moved to the present site one hundred yards down the road and reassembled. The Old Cottage features a local historical plaque, and is now used as a bridalwear shop.[18][19]

The Old Farmhouse[]

A large timber-framed and weatherboarded yeoman farmer's house, forming part of the Cheam Conservation Area with St Dunstan's Church, Whitehall, The Old Rectory and the Lumley Chapel, the Old Farmhouse has a crown post roof and large Tudor axial chimney stack in the centre with large fireplaces. The earliest part of the house is 15th century, with several building stages extending the house in the 16th and 17th centuries, creating a Baffle House design popular in the 17th century.

Many original features remain including oak doors and hinges, window shutters and fireplaces. Much of the timber framing is exposed throughout the house. Recent excavation and ground imaging uncovered a large Tudor kitchen underneath the house with a Tudor hearth and hood visible. Access to the cellar kitchen was by a staircase going north to south, which is now under the floor of the current kitchen. A file of text and images relating to the house is available in the Conservation Archive in Sutton Library.

Nonsuch Mansion[]

Nonsuch Mansion is a Grade II listed Gothic revival mansion within Nonsuch Park. The Service Wing Museum is open to the public during the summer on Sundays. It is run by the Friends of Nonsuch,[20] which charitable organisation also commissioned the largest model of Nonsuch Palace available. The model was created by designer Ben Taggart and can be seen throughout the year on Sundays.[21] The mansion itself is a popular place for wedding receptions, as is available for hire. In medieval times the land upon which Nonsuch Mansion sits was part of the three thousand acre manor of Cuddington. The mansion was originally built in 1731–1743 by Joseph Thompson and later bought by Samuel Farmer in 1799. He employed Jeffry Wyattville to rebuild it in a Tudor Gothic style in 1802–1806. Farmer was succeeded by his grandson in 1838 under whom the gardens became famous.

Nonsuch Mansion bears a resemblance in its design to the original design of Nonsuch Palace, whose construction was begun by King Henry VIII in the 16th century. Built within the north porch of the mansion is a block from the original Nonsuch Palace that bears an inscription which means "1543 Henry VIII in the 35th year of His reign."

Places of worship[]

St Dunstan's Church is the area's parish church, situated in Cheam Village, next to Lumley Chapel. St Paul's Howell Hill is on Northey Avenue at the far west of the town, although it is actually in the borough of Epsom and Ewell. It is known locally due to its prominent presence on a roundabout and its contemporary design. At the eastern end of Northey Avenue is St Andrews United Reformed Church. Cheam Baptist Church is located next to St Dunstan's Church. Cheam Methodist Church is in the east of the town just off the A217 and is also home to Sutton Schoolswork, the local Christian schools charity working in the borough of Sutton.

St Dunstan's Church[]

The parish church of St. Dunstan is Grade II* listed.[22] It was built in Cheam Village in 1864 next to Lumley Chapel on the site of a medieval church. It was built with Kentish ragstone below pitched slate roofs, with dressings to windows and doors in Bath Stone. It was designed by F. H. Pownall in the Gothic revival architectural style, and features polychrome brickwork decoration internally.[23] The lychgate, dated 1891, at the entrance to the churchyard, is listed Grade II.[24] In the churchyard are three tombs which are Grade II listed. [25][26][27]

The graveyard attached to this church was twice subject to a 6-foot (1.8 m) archaeological excavation by the police, first between June and September 2012, and again from April 2013.[28] This excavation was conducted in order to uncover evidence in the investigation into the unsolved disappearance of Lee Boxell, a fifteen-year-old local schoolboy, in 1988. The church was home to an informal youth club in the 1980s, known as 'The Shed'.[29]

Lumley Chapel[]

Situated next to St Dunstan's Church, Lumley Chapel is the oldest standing building in the London Borough of Sutton, and contains many notable monuments to local families.

Following the construction of the new St Dunstan's church in 1864, the older church on the site was demolished, other than the east end of the chancel, which was retained to contain the monuments and brasses from the old church. This remnant of the former church is now known as the Lumley Chapel.[30][31] It is constructed in partly roughcast rubble stone and brick, and has a gabled tile roof.[31] The east window dates from the 15th century and has three lights. In the south wall is the blocked arcade that formerly led into the south chapel.[30]

The remnant was declared "redundant" in 2002,[32] and vested in the Churches Conservation Trust.[33] It has been designated by English Heritage as a Grade II* listed building,[31] and is under the care of a national charity, the Churches Conservation Trust.[34]

Demography[]

38.2% of homes in Cheam are detached houses, 23% are semi-detached, 20.6% are flats/maisonettes/apartments, and 18.6% are terraced.[35]

Parks and gardens[]

Cheam is mainly built up, but retains Cheam Park and Nonsuch Park, the latter home to a historic building, Nonsuch Mansion and extensive flower gardens.

Cheam Park backs onto Nonsuch Park, with tennis courts, football pitches and a children's playground.

Schools[]

There are a number of schools in Cheam, including Nonsuch High School, a grammar school for girls and Cheam High School, a large mixed comprehensive school.[36]

Primary schools include Cuddington Croft, St Cecilias Catholic Primary School, Cheam Fields Primary, Cheam Common Primary, Cheam Park Farm Nursery and Infants School, Cheam Park Farm Juniors, Nonsuch Primary and St. Dunstans Church of England Primary.

Cultural references[]

In the comedy show Hancock's Half Hour, Tony Hancock lived in the fictional road Railway Cuttings, in East Cheam. Though not in existence today, the census of 1841 includes the place-names East Cheam, North Cheam, Garden Green and Cheam Common, which indicates that East Cheam did exist officially in name and was not fictional.

Cheam is referred to in a rhyme dating back to the 18th century, and revised in the Victorian era to:

"Sutton for good mutton;

Cheam for juicy beef;

Croydon for a pretty girl

And Mitcham for a thief."[37]

Disappearance of Lee Boxell[]

Lee Boxell, a 15-year-old schoolboy, disappeared near his home in Cheam on 10 September 1988. He was last seen outside of the then-Tesco supermarket (now an ASDA store) at 2:20pm. The case remains unsolved. It was featured in the national press and on BBC TV's Crimewatch.[38]

Film locations[]

St. Dunstan's Church was used in an episode of the TV comedy The I.T. Crowd, Series 2 ("Return of the Golden Child").[39][40][41]

Notable people[]

- Prince Philip (1921–2021), attended Cheam School in the early 1930s when the school was still in Cheam

- Koop Arponen (born 1984), a winner in the Finnish version of Pop Idol, attended Cheam High School

- David Bellamy (1933–2019), TV naturalist, attended Cheam Fields Primary School

- James Blades (1901–1999) orchestral percussionist.[42]

- Lee Boxell (born 1973), a schoolboy who disappeared on 10 September 1988 from Cheam

- Jane Dee, Elizabethan lady-in-waiting and wife of occultist John Dee, was born in Cheam

- Tony Hancock (1924–1968), comedian, lived in and set his sketches in Cheam

- Paul Greengrass (born 1955), film director, was born in Cheam

- James Hunt (1947–1993), Formula One racing driver, lived in Cheam as a child and attended Ambleside School

- Peter Manley (born 1962), darts player, was born in Cheam

- Jimmy Mann (born 1978), darts player, resides in Cheam, attended Cheam Fields primary school

- Joanna Rowsell (born 1988), Olympic cycling gold medallist, attended Cuddington-Croft Primary School and Nonsuch High School for Girls

- Alex Sawyer (born 1993), actor, lived in Cheam and attended The Avenue School for a while

- Harry Secombe (1921–2001), comedian, lived in Cheam for many years

- Alec Stewart (born 1963), (ex-England cricketer) lived in Cheam

- Jeremy Vine (born 1965) (presenter) and his brother Tim Vine (born 1967) (comedian) were born in Cheam

- Carrie Quinlan, actress, lived in Cheam and attended Nonsuch High School for Girls

- Dr Suzannah Lipscomb (born 1978), historian, lived in Cheam and attended Nonsuch High School for Girls.

Nearby places[]

References[]

- ^ "Sutton Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 'Parishes: Cheam', in A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 4, ed. H E Malden (London, 1912), pp. 194–199. British History Online (accessed 12 May 2018)

- ^ 'Parishes: Cheam', in A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 4, ed. H E Malden (London, 1912), pp. 194–199. British History Online (accessed 12 May 2018)

- ^ 'Charters of Chertsey Abbey, ed. S. E. Kelly, 2015'

- ^ Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, p.98.

- ^ Surrey Domesday Book Archived 15 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ http://www.commonwork.org/pdf/cheam.pdf[dead link]

- ^ Orton, Clive (1979), "Medieval pottery from a kiln site at Cheam : Part 1" (PDF), London Archaeologist (3): 300–304

- ^ Cheam Charter Fair website

- ^ Sutton Guardian January 2012

- ^ Sutton Guardian May 2012

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "The Old Rectory". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013.

- ^ Borough Heritage Study Archived 6 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Friends of Whitehall Homepage". Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Cheam -Combined -War Memorial, Cheam, Surrey, UK - World War I Memorials and Monuments on Waymarking.com".

- ^ Historic England, "Details from listed building database (1440363)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 30 June 2017

- ^ "Old Cottage, Cheam Village, Surrey, UK. - Relocated Structures on Waymarking.com".

- ^ Sutton Council Archived 4 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ http://www.friendsofnonsuch.co.uk[bare URL]

- ^ https://www.google.com/search?q=Ben+Taggart+Nonsuch+Palace&client=safari&rls=en&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwicjOa8qLveAhUD_qQKHXRxB8gQsAR6BAgFEAE&biw=1607&bih=903[bare URL]

- ^ Historic England, "Details from listed building database (1065676)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 28 March 2016

- ^ Church of England

- ^ Historic England, "Lychgate in the Churchyard of St Dunstan's, Sutton (1357594)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 20 August 2013

- ^ Historic England, "The tomb of Fleetwood Dormer d. 1736 in the Churchyard of St Dunstan's, Sutton (1382344)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 20 August 2013

- ^ Historic England, "The tomb of William Farmer c.1815 in the Churchyard of St Dunstan's, Sutton (1382345)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 20 August 2013

- ^ Historic England, "The tomb of Christian and Henry Neale d. 1675 and Eliza Dutton d. 1687 in the Churchyard of St Dunstan's, Sutton (1382351)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 20 August 2013

- ^ "Graveyard searched for signs of Lee Boxell, who went missing in Sutton". Evening Standard. 21 September 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Paedophiles active when boy vanished". 15 February 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Malden, H. E., ed. (1912), "Parishes: Cheam", A History of the County of Surrey, Victoria County History, University of London & History of Parliament Trust, 4, pp. 194–199, retrieved 30 March 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Historic England (2011), "Remains of Old Church of St Dunstan, Now known as the Lumley Chapel, Sutton (1183440)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 18 April 2011

- ^ Schemes, Diocese of Southwark, retrieved 30 March 2011

- ^ Diocese of Southwark: All Schemes (PDF), Church Commissioners/Statistics, Church of England, 2011, p. 8, retrieved 30 March 2011

- ^ Lumley Chapel (St Dunstan's), Cheam, Surrey, Churches Conservation Trust, retrieved 30 March 2011

- ^ https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/ward-profiles-and-atlas[bare URL]

- ^ Ofsted: Cheam High School Inspection report[permanent dead link] (2010)

- ^ "Chapter XIV: Local Allusions to Women". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ "BBC One: Crimewatch – Lee Boxell disappearance". BBC. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013.

- ^ Sutton Guardian 22 July 2009

- ^ Sutton Film Office

- ^ Film Fixer[better source needed]

- ^ Mattey, Peter. "History of our area". Belmont and South Cheam Residents Association. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cheam. |

- Cheam at Curlie

- Hancock's Legacy David McKie in The Guardian, 30 November 2006.

- Areas of London

- Districts of the London Borough of Sutton