Child tax credit (United States)

| This article is part of a series on |

| Taxation in the United States |

|---|

|

|

|

The United States federal child tax credit (CTC) is a tax credit for parents with dependent children. For the year 2021, it is fully-refundable and provides $3,600 in annual tax relief for each child under the age of 6 and $3,000 for each child between the ages of 6 and 17. It begins to phase out for single filers at $75,000 in annual income, for unmarried heads of households at $112,500, and for married joint filers at $150,000. It is scheduled to revert to a narrower, partially-refundable credit of $2,000 per eligible child (with up to $1,400 of that refundable, subject to an earned income threshold and phase-in) after the expansion of the credit instituted by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 expires in 2022. The pending Build Back Better Act would extend the expansion for an additional year and make full-refundability permanent.

The CTC was estimated to have lifted about 3 million children out of poverty in 2016.[1] In 2021, a Columbia University study estimated that the expansion of the CTC in the American Rescue Plan Act reduced child poverty by an additional 26%, and would have decreased child poverty by an additional 40% had all eligible households claimed the credit.[2] The same Columbia group found that in the first month after the expansion of the CTC expired, child poverty rose from 12.1% to 17%; they concluded, "The 4.9 percentage point (41 percent) increase in poverty represents 3.7 million more children in poverty due to the expiration of the monthly Child Tax Credit payments".[3]

Overview[]

Structure[]

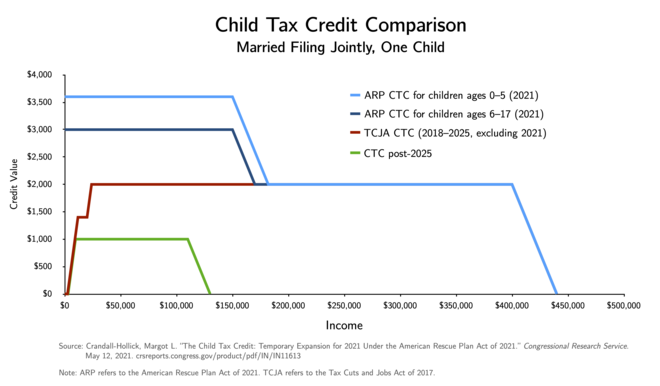

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), for the years 2018–2025 (excluding 2021, see below section Temporary Expansion in 2021) the CTC allows taxpayers to reduce their federal tax liability by $2,000 per qualifying child (see Eligibility). The maximum credit a taxpayer can receive is thus equal to the number of qualifying children multiplied by $2,000 (e.g. a family with 3 qualifying children is eligible for $2000 x 3 = $6,000 in tax relief). The credit begins to phase out at a rate of $50 for every $1,000 in additional income over $200,000 for single filers and unmarried heads of households or over $400,000 for married joint filers.[4]

Many taxpayers whose incomes are too low to claim the full $2,000 credit (i.e. they have tax liabilities below $2,000) are eligible for the additional child tax credit (ACTC), a phased-in $1,400 refundable tax credit.[5] For example, if a taxpayer has an income making them eligible for the full ACTC has one qualifying child and a tax liability of $100, then they can use $100 of the CTC to reduce their tax liability to $0 and then claim the full $1,400 ACTC (which will be refunded to them) for a total benefit of $1,500. Note, however, that the sum of the ACTC and CTC cannot exceed the maximum credit of $2,000.[6] For instance, a taxpayer with one qualifying child with an $800 tax liability can use $800 of the CTC to reduce their tax liability to $0, but can only claim $1,200 of the ACTC, for the maximum allowable benefit of $2,000.

However, not all low-income taxpayers with qualifying children are eligible for the full ACTC—or even any of the ACTC. The ACTC has an income threshold of $2,500 (i.e. a family must make at least $2,500 in income to claim the credit) and phases in at a rate of 15% of earned income above $2,500 up to the maximum-allowable $1,400 per child.[7] For example, a taxpayer who makes $8,000 in income and has at least one qualifying child is eligible for .15($8,000–$2,500)=$825 of the ACTC. Notice that the income range of the phase-in increases with the number of qualifying children: a taxpayer making $30,000, for instance, could claim the full ACTC if they have one child (since .15($30,000 – $2,500) = $4,125 is greater than the maximum allowable $1,400 for one child) but could not claim the full credit if they have three children (since .15($30,000 – $2,500) = $4,125 is less than the maximum allowable $1,400 x 3 = $4,200 for three children).

The Congressional Research Service estimates that about 1 in 5 taxpayers with eligible children fall into the phase-in range (i.e. they had incomes too low to receive the maximum credit).[6]

Temporary Expansion in 2021[]

The child tax credit was expanded for one year under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP). The ARP increased the credit to $3,600 per child under the age of 6 and $3,000 per child between the ages of 6 and 17 (note also that it increased the maximum age for an eligible child from 16 to 17). More specifically, it increased the tax credit to $3,600/$3,000 per child for single filers with incomes below $75,000, for unmarried heads of households with incomes below $112,500, and for married joint filers with incomes below $150,000. The credit phases down to a $2,000 credit (the value of the old CTC) above these income levels, remains at $2,000 until income reaches $200,000 for single filers and unmarried heads of households or $400,000 for married joint filers, and then phases down to $0.[8]

The ARP also made the credit fully refundable (i.e. it eliminated the income threshold and phase-in) and offered the option of receiving half of the credit as advance monthly payments, with the other half received as a credit when filing taxes in early 2022. Full refundability made the full value of the credit available to lower-income families, who previously tended to receive little or no benefit.[a][8]

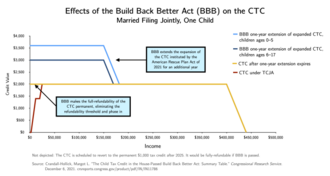

The expansion is scheduled to expire in 2022. However, the pending Build Back Better Act would extend the expansion for an additional year and make the full refundability of the CTC permanent (i.e. in 2023 the CTC would revert to the $2,000 benefit but be fully refundable).[9]

Post-2025[]

The $2,000 child tax credit instituted by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) is scheduled to expire in 2025. After that point, the credit will revert to the CTC made permanent by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA). Under the ATRA, the CTC is a $1,000 non-refundable credit that begins to phase out at a rate of $50 for every $1,000 of income above $75,000 for single filers and unmarried heads of households or $110,000 for married couples filing jointly.[6]

Families receiving less than the non-refundable $1,000 child tax credit are eligible for the $1,000 additional child tax credit (ACTC). The ACTC is refundable but has an earned income threshold of $3,000 (i.e. families must make at least $3,000 to claim the credit) and phases in at a rate of 15% of earned income above $3,000.[4] The sum of the ACTC and CTC claimed by a taxpayer cannot exceed the maximum credit of $1,000.

Related credits[]

The child and dependent care credit allows eligible taxpayers to deduct $3,000 per child for certain childcare services, capped at a total of $6,000 annually per taxpayer.[10] The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 created an additional dependent credit, allowing families to claim an additional $500 for an aging parent or older child requiring special care.[11]

Comparison chart[]

The below chart displays the differences between the three forms of the child tax credit explained above for joint filers.

Eligibility[]

The child tax credit is available to taxpayers who have a "qualifying child." A person is a "qualifying child" if they are under the age of 17 (or, in 2021, under the age of 18) by the end of the taxable year and meets the requirements of 26 U.S.C. Sec. 152(c). In general, a qualifying child is any individual for whom the taxpayer can claim a dependency exemption and who is the taxpayer's son or daughter (or descendant of either), stepson or stepdaughter (or descendant of either), or eligible foster child. For unmarried couples or married couples filing separately, a qualifying child will be treated as such for the purpose of the CTC for the taxpayer who is the child's parent, or if not a parent, the taxpayer with the highest adjusted gross income (AGI) for the taxable year in accordance with 26 U.S.C. Sec. 152(c)(4)(A).

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 restricted the credit to only those dependent children possessing a Social Security Number (SSN); previously, dependents who did not possess a SSN because of their immigration status could still be eligible for the credit using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN).[12]

History[]

Origins[]

The child tax credit was created in 1997 as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997.[13] Initially it was a $500-per-child (up to age 16) nonrefundable credit intended to provide tax relief to middle- and upper-middle-income families. The credit phased out for higher earners at a rate of $50 for every $1,000 in additional income over $110,000 for taxpayers filing as married joint, $75,000 for taxpayers filing as head of household, and $55,000 for taxpayers filing as married separate. While non-refundable for most families, it was refundable for families with more than three children (reduced by the amount of the taxpayer’s alternative minimum tax). The credit was not indexed for inflation.

Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA)[]

A number of significant changes were made to the child tax credit by the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA), a signature piece of tax legislation during the George W. Bush presidency (the bill is often referred to as one of the two "Bush tax cuts"). According to Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, a specialist in public finance, the bill made four key alterations to the CTC:[13]

- It increased the maximum amount of the credit per child in scheduled increments until it reached $1,000 per child in 2010

- It made the credit refundable for families irrespective of size using the earned income formula (10% of a taxpayer’s earned income in excess of $10,000, up to the maximum amount of the credit for that tax year, and scheduled to increase to 15% for tax years 2005 through 2010)

- It allowed the child tax credit to offset alternative minimum tax liability

- It temporarily repealed the prior law provision that reduced the refundable portion of the child tax credit by the amount of the AMT

All of these provisions were scheduled to expire at the end of 2010 (restrictions imposed by the rules of budget reconciliation, a special parliamentary procedure that allows expedited passage of certain budgetary legislation, often requires placing time limits on budget policies, even if legislators hope they will be made permanent).

Adjustments to EGTRRA[]

The Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA) increased the size of the CTC to $1,000 for 2003 and 2004 (under EGTRRA, the credit would not have reached $1,000 until 2010). The Working Families Tax Relief Act of 2004 extended this amount through 2010.[14] The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 extended this $1,000 cap through the end of 2012.[15] The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, signed into law by President Barack Obama, made the $1,000 cap permanent.[16]

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA)[]

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), with efforts led by Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Ivanka Trump, made three major changes to the CTC:[11]

- It doubled the amount per qualifying child to $2,000

- It made up to $1,400 of the credit refundable

- It increased income thresholds to make the CTC available to more families.

Before 2018, the full CTC was only available to single parents making less than $75,000 and families making less than $110,000 per year. The TCJA dramatically increased these income thresholds to $200,000 for single parents and $400,000 for married couples filing jointly. Above these limits, the CTC is phased out at the rate of $50 for each additional $1,000 (or portion of $1,000) earned.[17]

Expansion Proposals[]

In 2019, Democratic senators Michael Bennet and Sherrod Brown proposed the American Family Act (AFA) of 2019,[18] which garned 38 co-sponsors (all Democrats) and became the centerpiece of Bennet's 2020 presidential campaign.[19] The bill would have increased the child tax credit's refundable portion to $3,600 per child under age six and to $3,000 per child age six to 16,[20] eliminated the income threshold and phase-in (opening up the credit to the lowest-income families), removed the requirement added by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 that dependents have a Social Security number to qualify (which made non-citizen children ineligible) and made the credit a monthly rather than annual benefit.[21] It would also have significantly lowered the phase-out income threshold, reducing the number of high- and upper-middle income households who could use the credit, as well as increase the rate at which the credit phases out.[21]

It was estimated that the AFA would have reduced child poverty by roughly a third[22] at a cost of approximately $100 billion in lost tax revenue annually.[23] However, with the Senate under Republican control, the bill failed to advance; the proposal did ultimately influence the expanded child tax credit included in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (see section below).

The proposed inclusion of an expanded CTC in the American Rescue Plan also spurred the creation of several alternative child benefit proposals. In February 2021 (shortly after Joe Biden assumed the presidency and Democrats gained a narrow majority in the Senate), Republican Senator Mitt Romney released his "Family Security Act", a proposal to provide families with a yearly benefit of $3,000 per child ages 6–16 and $4,200 per child ages 0–5, with a maximum allowable benefit of $15,000 and the same phaseout structure as the CTC under the TCJA.[24][25] Like the child tax credit expansion proposed in the American Family Plan and instituted in the American Rescue Plan Act, the benefit would be delivered as monthly payments, though it would also allow families to begin claiming the benefit four months before the expected birth date of their child.[25] Unlike the Democratic proposals, Romney's plan would have the benefit administered by the Social Security Administration (SSA) rather than the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).[b] Though the child benefit would be larger under Romney's plan (except for large families, who would have their benefit capped under Romney's plan), it would do less to reduce child poverty because Romney's plan would have eliminated Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, and the head of household tax filing status.[24][26] Romney also proposed eliminating the state and local tax deduction (which primarily benefits wealthy households and has a negligible effect on child poverty) to raise revenue for the benefit.[24]

In April 2021, Republican Senator Josh Hawley introduced a related proposal called the "Parent Tax Credit" (PTC).[27] The PTC would have been a new, refundable tax credit of $6,000 annually for single parents with at least one child under the age 13 and $12,000 annually for married couples with at least one child under the age of 13 (the larger benefit for married couples was intended to act as a "marriage bonus"[28]); the benefit would be paid out monthly (i.e. $500 per month for single parents and $1,000 per month for married couples).[29] It would have had a larger income threshold than the CTC, requiring parents to make at least $7,540 in income (the equivalent of 20 hours of work per week at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour) to claim the credit; it would have no income phase-out. Children would need to possess a Social Security number to qualify.

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021[]

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) of 2021, a stimulus bill advanced by Democratic lawmakers and signed into law by President Joe Biden in response to the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, expanded the child tax credit by allowing qualifying families to offset, for the 2021 tax year, $3,000 per child up to age 17 and $3,600 per child under age 6. The size of the benefit gradually diminished for single filers earning more than $75,000 per year, heads of households earning more than $112,500 per year, and married couples filing jointly making more than $150,000 a year. Additionally, it made the credit is fully refundable, and half of the benefit was sent out to eligible households as monthly payments (i.e. it was delivered as 6 monthly payments + one lump-sum payment for the remaining half of the benefit). Full refundability made the full value of the credit available to lower-income families, who previously tended to receive little or no benefit.[a][8]

39 million households covering 88% of children in the United States began receiving payments automatically on July 15, 2021.[30]

Build Back Better Act[]

The Build Back Better Act, currently under consideration in the Senate after it was passed by the House of Representatives on November 19, 2021,[31] would extend the expansion of the CTC made by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 for one year.[32] Significantly, it would also make the full-refundability of the CTC permanent (i.e. it would permanently eliminate the earned income threshold and phase-in, so that low-income families can access the full value of the credit).[12]

Effects[]

The child tax credit—especially the fully-refundable 2021 expanded child tax credit—significantly reduces child poverty.[2][1] According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, in 2018 the CTC, in conjunction with the Earned income tax credit, lifted 5.5 million children above the poverty line.[33] Research suggests that income from the CTC and EITC leads to improved educational outcomes for young children in low-income households and is associated with significant increases in college attendance among high school seniors in low-income families.[34]

Two surveys of people who claimed the 2021 expanded child tax credit, one by the United States Census Bureau and another by the University of Michigan in collaboration with Propel, a technology firm focused on the finances of low-income people, found that most families used the monthly CTC payments to pay for basic needs like food, rent, school supplies and clothing, as well as to pay utilities bills and reduce personal debt.[35][36][37] One study examining the effects of the first two payments of the 2021 child tax credit expansion found that the expanded CTC reduced food insufficiency among low-income households with children by 25% (the researchers also predict that this percentage will increase as uptake of the CTC by non-filers increases—when considering only families who received the CTC, food insufficiency decreased by 50%).[38] Researchers from the Social Policy Institute at Washington University in St. Louis found that the 2021 expanded child tax credit did not affect the labor rate and increased self-employment and small business formation.[39]

A Columbia University study estimated that the expansion of the CTC by the American Rescue Plan Act reduced child poverty by 26%, and would have decreased child poverty by 40% had all eligible households claimed the credit.[40] The same Columbia group found that in the first month after the expansion of the CTC expired, child poverty rose from 12.1% to 17%; they concluded, "The 4.9 percentage point (41 percent) increase in poverty represents 3.7 million more children in poverty due to the expiration of the monthly Child Tax Credit payments".[41]

Criticism[]

Child allowance alternatives[]

The child tax credit is a tax expenditure, i.e. a social benefit administered through the tax code. Accordingly, it is delivered as most tax breaks are: as a reduction in the amount of taxes a taxpayer owes to the government or, for the refundable portion, as a lump-sum payment delivered at the end of the tax year (the temporary expansion of the CTC for the year 2021, however, allowed beneficiaries to receive half of the CTC as a series of six monthly payments, with the other half delivered as a lump-sum payment at the end of 2021).

A number of scholars and political commentators have argued that a child allowance (a simple direct cash payment to parents) would be more effective than the CTC at easing the costs of childcare and reducing child poverty.[42][43][44] According to a 2018 assessment published in the Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, converting the CTC and child tax exemption into a universal, monthly child allowance "would reduce child poverty by about 40 percent, deep child poverty by nearly half, and would effectively eliminate extreme child poverty."[43]

Complexity[]

The child tax credit has been criticized for its complexity. In many countries, a simple monthly child allowance is sent to all families.[45] In the United States, by contrast, the CTC has a complicated structure: it includes an income threshold, a phase-in formula, a separate phase-out formula, and mixes reduction of tax liability with direct payments. The 2021 expansion scrapped the income threshold and phase-in, but has a more complicated phase-out structure: it first phases down to a $2,000 plateau and then at higher incomes phases down to $0; the phase-out structure also differs depending on the number of qualifying children (see chart).[26][46]

The CTC also interacts with other tax credits in ways that may be confusing to claimers. Many families can simultaneously claim the child tax credit, exemptions for dependents, the Earned Income Tax Credit and the child and dependent care tax credit—each with its own set of eligibility rules—and may find it difficult to understand how these programs interact with each other or even which programs they are eligible for.[47] The large number of tax benefits also makes tax forms long and confusing.[48] According to the US Treasury:[49]

[E]ligibility rules for refundable credits are complex and lead to high improper payment rates...[R]ules differ by credit and are complex because they must address complicated family relationships and residency arrangements to determine eligibility...The complexity of the rules causes taxpayers to erroneously claim the credits. Much of the complexity that leads to errors stems from claims involving qualifying children. This is because of the intricacy of the rules regarding who can claim a child in instances of divorce, separation, and three-generation families. The complexity of these rules increases compliance burden for taxpayers and administrative costs for the IRS...Our analysis of EITC and ACTC eligibility rules found that the qualifying child relationship rules are difficult to understand. In addition, the definition of key eligibility requirements is different between the two credits. This can cause confusion for taxpayers when trying to determine which credit(s) they are eligible to claim.

Administrative difficulties[]

One criticism leveled against the CTC focuses on the Internal Revenue Service's (IRS) inability to deliver benefits to all eligible households, particularly low-income households.[50] This became especially acute during the temporary expansion of the CTC in 2021, which made the lowest income families eligible for the full benefit for the first time (prior to the change, the CTC had an income threshold and phase-in, so administrative problems affecting low-income families largely did not exist for the simple reason that low-income families were ineligible for the benefit). To determine eligibility, the IRS uses taxpayers' tax returns. Many low-income households, however, are not required to file tax returns.[51][52] As a result, many eligible low-income families may not receive the CTC despite being eligible for it.

The IRS attempted to remedy this by offering an online non-filer sign-up tool. However, that, too, has been criticized. It was derided for being poorly designed: the website, designed in conjunction with Intuit through the Free File Alliance,[53] was not mobile friendly, contained little indication that it was an official government portal (it used a .com rather than .gov domain name, for instance), and was only available in English.[54][55][56] To log in to the website, users faced a number of requirements that ordinary taxpayers do not have to satisfy when filing their tax returns, including providing an email address, receiving a log-in code on their phone, scanning a photo ID, and taking a picture of themselves with a computer or smartphone (which is run through facial recognition software)—all administrative burdens that make completing the online form more difficult, particularly for low-income families.[57] (The Biden White House collaborated later that year with Code for America to create a more accessible website).[58][59] Critics also noted that relying on non-filers to sign up online fails to accommodate people without access to the internet, which especially impacts low-income people (according to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), more than one in six people in poverty do not have internet access in their home[60])—precisely the group that is most likely not to file and the group that reaps the greatest relative gain in income from the refundable CTC.[54]

See also[]

- Earned Income Tax Credit

- Social programs in the United States

- Tax expenditure

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

Notes[]

- ^ a b In practice, however, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) faced a number of administrative difficulties when determining eligibility for the CTC, which reduced the number of low-income households who received the credit. See Criticism: Administrative difficulties section.

- ^ Having the Social Security Administration (SSA) administer the benefit rather than the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) would alleviate many of the administrative problems that beleaguered the 2021 expanded child tax credit. See Administrative difficulties.

References[]

- ^ a b M.S.R. (16 October 2017). "Why Ivanka Trump wants to extend the child tax credit". The Economist.

- ^ a b Parolin, Zachary; Collyer, Sophie; Curran, Megan A.; Wimer, Christopher (August 20, 2021). "Child poverty drops in July with the Child Tax Credit expansion" (PDF). Center on Policy and Social Policy. Columbia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ "Absence of Monthly Child Tax Credit Leads to 3.7 Million More Children in Poverty in January 2022". Center on Poverty & Social Policy. Columbia University. February 17, 2022. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Expanded Child Tax Credit for 2021: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". Congressional Research Service. November 1, 2021. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Child Tax Credit: For use in preparing 2017 Returns" (PDF). Internal Revenue Service. January 23, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Child Tax Credit: Selected Legislative Proposals in the 116th Congress". Congressional Research Service. August 28, 2020. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "What's new with the child tax credit after tax reform". Internal Revenue Service. November 27, 2018. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Child Tax Credit: Temporary Expansion for 2021 Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA; P.L. 117-2)". Congressional Research Service. May 12, 2021. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ Zhou, Li; Leber, Rebecca; Scott, Dylan; Matthews, Dylan (October 28, 2021). "What's in — and what's out of — Biden's latest spending proposal". Vox. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ "Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit for 2018, 2019". American Tax Service. 2018-12-11. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- ^ a b CFP, Matthew Frankel (2018-01-09). "The 2018 Child Tax Credit Changes: What You Need to Know -". The Motley Fool. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- ^ a b Marr, Chuck; Cox, Kris; Sherman, Arloc (November 11, 2021). "Build Back Better's Child Tax Credit Changes Would Protect Millions From Poverty — Permanently". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Archived from the original on November 30, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Crandall-Hollick, Margot L. (March 1, 2018). "The Child Tax Credit: Legislative History" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ "NYSSCPA | The New York State Society of CPAs". www.nysscpa.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

- ^ "TAX RELIEF, UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE REAUTHORIZATION, AND JOB CREATION ACT OF 2010". gpo.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ^ Nunns, James R.; Rohaly, Jeffrey (2013-01-08). "Tax Provisions in the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA)". Tax Policy Center. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

- ^ "Child Tax Credit" (PDF). irs.gov. Internal Revenue Service. 2015-01-01. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ^ Bennet, Michael F. (2019-03-06). "S.690 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): American Family Act of 2019". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ Wingerter, Justin (April 30, 2021). "How Colorado's senior senator Michael Bennet helped create a major anti-poverty program". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "The child tax credit: Onward and upward?". American Enterprise Institute - AEI. 2020-03-16. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ a b Crandall-Hollick, Margot L. (March 26, 2019). "How Would the American Family Act Change the Child Tax Credit?" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (May 2, 2019). "Democrats have united around a plan to dramatically cut child poverty". Vox.

- ^ "T19-0006 - Expand the Child Tax Credit (CTC); Baseline: Current Law; Impact on Tax Revenue ($ billions), 2019-28". Tax Policy Center. 2019-04-01. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ a b c Rainey, Rebecca (February 4, 2021). "Romney proposes child care benefit for families, fueling Democrats' push". Politico.

- ^ a b "The Family Security Act" (PDF). Official Website of US Senator Mitt Romney. February 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Matthews, Dylan (February 23, 2021). "What Democrats can learn from Mitt Romney". Vox. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Zeballos-Roig, Joseph (April 26, 2021). "Sen. Josh Hawley wants to send $1,000 monthly checks to families with kids under 13 but provide less to single parents". Insider Inc. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Fordham, Evie (April 26, 2021). "Hawley proposes $12K tax credit for married parents with kids under 13". Fox News.

- ^ "Senator Hawley Introduces Parent Tax Credit—Historic Relief for Working Families". Official Website of US Senator Josh Hawley. April 26, 2021. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "Treasury and IRS Announce Families of 88% of Children in the U.S. to Automatically Receive Monthly Payment of Refundable Child Tax Credit". IRS. Internal Revenue Service. 17 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Cochrane, Emily; Weisman, Jonathan (November 19, 2021). "House Narrowly Passes Biden's Social Safety Net and Climate Bill". The New York Times.

- ^ Siegal, Rachel (November 19, 2021). "How the House spending bill changes the child tax credit". The Washington Post.

- ^ Marr, Chuck; Cox, Kris; Hingtgen, Stephanie; Windham, Katie (May 24, 2021). "Congress Should Adopt American Families Plan's Permanent Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC, Make Additional Provisions Permanent". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Marr, Chuck; Huang, Chye-Ching; Sherman, Arloc; DeBot, Brandon (October 1, 2015). "EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children's Development, Research Finds" (PDF). Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Washington, Kemberley (August 30, 2021). "How Monthly Child Tax Credit Payments Are Impacting Americans' Finances". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 26, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "Week 35 Household Pulse Survey: August 4 – August 16". United States Census Bureau. August 25, 2021.

- ^ Pilkauskas, Natasha; Cooney, Patrick (October 6, 2021). "Receipt and Usage of Child Tax Credit Payments Among Low-Income Families: What We Know". Poverty Solutions. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ Parolin, Zachary; Ananat, Elizabeth; Collyer, Sophie M.; Curran, Megan; Wimer, Christopher (September 2021). "The Initial Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Material Hardship". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w29285.

- ^ Hamilton, Leah; Roll, Stephen; Despard, Mathieu; Maag, Elaine (September 2021). "Employment, Financial and Well-being Effects of the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit: Wave 1 Executive Summary". Social Policy Institute Research. doi:10.7936/kkqf-rk07 – via Washington University Open Scholarship.

- ^ Parolin, Zachary; Collyer, Sophie; Curran, Megan A.; Wimer, Christopher (August 20, 2021). "Child poverty drops in July with the Child Tax Credit expansion" (PDF). Center on Policy and Social Policy. Columbia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ "Absence of Monthly Child Tax Credit Leads to 3.7 Million More Children in Poverty in January 2022". Center on Poverty & Social Policy. Columbia University. February 17, 2022. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Wunder, Timothy A. (May 13, 2019). "Fighting Childhood Poverty: How a Universal Child Allowance Would Impact the U.S. Population". Journal of Economic Issues. 53 (2): 537–544. doi:10.1080/00213624.2019.1603769 – via Taylor & Francis.

- ^ a b Shaefer, H. Luke; Collyer, Sophie; Duncan, Greg; Edin, Kathryn; Garfinkel, Irwin; Harris, David; Smeeding, Timothy M.; Waldfogel, Jane; Wimer, Christopher; Yoshikawa, Hirokazu (February 1, 2018). "A Universal Child Allowance: A Plan to Reduce Poverty and Income Instability Among Children in the United States". The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. 4 (2): 22–42. doi:10.7758/RSF.2018.4.2.02. ISSN 2377-8253. PMC 6145823. PMID 30246143.

- ^ VerValin, Joe (October 5, 2018). "The Case for a Universal Child Allowance in the United States". Cornell Policy Review. Archived from the original on November 2, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "Family cash benefits" (PDF). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. July 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Bruenig, Matt (February 8, 2021). "The Newest CTC Proposal Is Still a Mess". People's Policy Project. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Sawhill, Isabel V.; Welch, Morgan (May 27, 2021). "The American Families Plan: Too many tax credits for children?". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Hungerford, Thomas L.; Thiess, Rebecca (September 23, 2021). "The Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "Addressing Complex and Inconsistent Earned Income Tax Credit and Additional Child Tax Credit Rules May Reduce Unintentional Errors and Increase Participation" (PDF). US Treasury. September 23, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ Birenbaum, Gabby (July 29, 2021). "How to make the child tax credit more accessible". Vox. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Cox, Kris; Caines, Roxy; Sherman, Arloc; Rosenbaum, Dottie (August 5, 2021). "State and Local Child Tax Credit Outreach Needed to Help Lift Hardest-to-Reach Children Out of Poverty". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ "What Could Have Been for the Child Benefit". People's Policy Project. Retrieved 2021-08-26.

- ^ Zeballos-Roig, Joseph (June 29, 2021). "The IRS's child tax credit portal 'looks like crap and it's not really usable' for low-income Americans trying to get $300 monthly federal payments". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Williams, Paul E. (June 18, 2021). "The Child Tax Credit Non-Filer Tool Is a Mess". People's Policy Project. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Golshan, Tara (June 18, 2021). "Democrats Have A Plan To Slash Child Poverty, But It Goes Through A Shoddy Website". HuffPost. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ LeBlanc, Cameron (July 19, 2021). "Why Many of the Poorest Parents Didn't Receive Their Child Tax Credit Payment". Fatherly. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ Pilkauskas, Natasha; Cooney, Patrick (October 2021). "Receipt and Usage of the Child Tax Credit Payments Among Low-Income Families: What We Know" (PDF). Poverty Solutions. University of Michigan. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 13, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ "Child Tax Credit for Non-Filers". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on September 2, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Gailey, Alex (September 9, 2021). "Child Tax Credit Payments Just Got Easier for More Americans to Sign Up For, Thanks to a New Online Tool". Time.

- ^ Swenson, Kendall; Ghertner, Robin (March 2021). "People in Low-Income Households Have Less Access to Internet Services – 2019 Update" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- Tax credits

- Taxation in the United States

- Personal taxes in the United States

- Child welfare in the United States