Children's poetry

This article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Children's poetry is poetry written for, or appropriate for children. This may include folk poetry (for example, Mother Goose rhymes); poetry written intentionally for young people (e.g. Shel Silverstein); poetry written originally for adults, but appropriate for young people (Ogden Nash); and poems taken from prose works (Lewis Carroll, Rudyard Kipling).

History[]

Early children's poetry[]

Poetry is universal throughout the world's oral traditions as songs and folklore passed down to younger generations. The oldest works of children's poetry, such as Zulu imilolozelo, are part of cultural oral traditions.[1]

In China, thanks to the invention of movable type, the Tang dynasty became known as the Golden Age of Chinese poetry. Some poets chose to wrote poems specifically for children, often to teach moral lessons. Many poems from that era, like "Toiling Farmers", are still taught to children today.[2]

In Europe, written poetry was uncommon before the invention of the printing press. Most children's poetry was still passed down through the oral tradition. However, some wealthy children were able to access handmade lesson books written in rhyme.[3]

With the invention of the printing press, European literature exploded. The earliest printed poetry for children is nearly all educational in nature. In the fifteenth century and sixteenth century, courtesy books aimed at children sought to teach them good manners and appropriate behaviour. Les Contenances de la Table, published in 1487, is a French example;[3] The Babee's Boke and Queene Elizabethe’s Achademy are both English examples, printed in the 1500s.[4]

The first children's book printed in the New World was John Cotton's Milk for Babes, Drawn out of the Breasts of Both Testaments, Chiefly for the Spirituall Nourishment of Boston Babes in either England, but may be of like Use for any Children. Published in 1646, it was a child's Puritan catechism.[5] While the first edition was not in verse, later editions were rewritten into the earliest American children's poetry.[3]

Another notable work of early children's poetry is John Bunyan's A Book for Boys and Girls, first published in 1686, and later abridged and re-published as Divine Emblems.[3] It consists of short poems about common, everyday subjects, each in rhyme, with a Christian moral.[4]

Eighteenth century[]

In the eighteenth century, a separate genre of children's literature, including poetry, began to emerge.[6]

As before, many works of children's poetry were written to teach children moral virtues. Isaac Watts' Divine Songs are probably the most famous examples. They were reprinted for a hundred and fifty years, in six or seven hundred editions.[3] The Divine Songs were regularly printed in chapbooks and were adapted by other writers to fit different Christian belief systems.[4] In fact, they were so popular that Lewis Carroll parodied them two hundred years later in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[7] JR Townshend argues that Isaac Watts was the first true poet for children.[3]

At the same time, for the first time since the invention of the printing press, children's poetry was being written to entertain. Nursery rhymes became popular for children in the mid-eighteenth century. The first published book of children's nursery rhymes was likely Tommy Thumb's Song Book, published in 1744 by a woman named Mrs. Cooper.[3] Most of the nursery rhymes contained in the Song Book are familiar to modern audiences, and were most likely passed through the oral tradition before being written down. If there's an earlier collection of nursery rhymes, it hasn't survived.[4]

In the late eighteenth century, John Newbery, the first publisher of English children's books, began to publish children's poetry. It's disputed whether he was the first to use the name of Mother Goose—some scholars argue that he published a collection of Mother Goose rhymes in the 1760s, but no evidence of that collection exists. A 1781 advertisement placed in the London Chronicle advertises Mother Goose's Melody for sale—but again, no copies have survived. We do, however, have an American edition published in 1785 by Isaiah Thomas- possibly pirated from the Newbery version.[3]

Newbery also published A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, the other important work of children's poetry from the period. The Pocket-Book is significant for two reasons: it was one of the first works of children's literature intended to entertain children as well as educate them, and it was one of the first works of children's literature to combine poetry, prose, alphabets, and moral lessons. Many of the poems in the Pocket-Book are about simple children's pastimes, like flying a kite, fishing, or blind man's bluff.[8]

Nineteenth century[]

In the nineteenth century, children's poets continued to write for children's entertainment. Ann Taylor and Jane Taylor wrote several books of children's poetry that contained poems such as "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star" and "My Mother".[3] The Cambridge History of English and American Literature claims that their poems are 'proverbial'; its editor states, "It has been alleged that Ann Taylor's My Mother is the most often parodied poem ever written; but Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star must run it very close."[4]

Children's poetry also continued to be used for moral education. Cautionary tales like Miss Turner's Cautionary Stories became popular around this time, and were reprinted well into the twentieth century.[4] These 'cautionary tales' follow the pattern of the Divine Songs and Courtesy Books of past centuries- they are short verses about children who do something terrible and face the consequences.[9] They became enough of a cultural staple to be parodied by writers such as Hilaire Belloc and Edward Gorey.[10] Other moralist authors, like Charles and Mary Lamb, wanted to educate more than preach. Their best-known work for children, Tales from Shakespeare, attempted to simplify and censor the works of William Shakespeare to be suitable for young minds. Critics praised the clarity of the writing, but even at the time, argued that it might be too complicated for children to understand.[4]

But society was beginning to see childhood as a different state from adulthood, an innocent state that should be focused on gentle education and play.[7] One of the most significant works from the early nineteenth century was William Roscoe's 1807 The Butterfly's Ball, and the Grasshopper's Feast, a short poem about insects attending a party. The Butterfly's Ball is one of the first rhyming picture books written in English, and one of the first intended solely to entertain. Originally written for Roscoe's son Robert,[4] it became a popular chapbook, and was even set to music for the Princess Mary.[11] It spawned two sequels-- The Butterfly's Funeral and The Butterfly's Birth-Day[11] - and a host of imitators, including The Peacock at Home and The Lion's Masquerade.[4]

Critics at the time adored The Butterfly's Ball for its whimsy, calling it a 'pretty idea', but many critics struggled with its lack of a moral. Mary Leadbetter said, "I apprehend Roscoe's Butterfly's Ball must have been written to remove the dread and disgust of insects so prone to fasten upon the youthful mind, and if it could prevent this evil early in life it must be allowed to be a meritorious performance."[11] Modern critics are less fond of it, calling it an "overly long talking animal verse poem". But its significance cannot be understated, and all modern picture books owe something to its influence.[3]

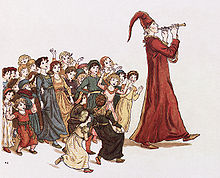

Other stories-in-verse followed, including A Visit From Saint Nicholas (better known as 'Twas the Night before Christmas) and Robert Browning's The Pied Piper of Hamelin. These works, written by 'respectable' members of society, proved that public opinion was changing. Children's literature was as likely to be fanciful as it was moralizing.[3] Around this time, the Brothers Grimm began collecting folklore. Romantic ideals of nationalism and aestheticism suddenly gave fairy tales a new significance. Many nineteenth century authors began to write new fairy tales, some in prose and some in verse.[4]

This new cultural acceptance of whimsy and lack of meaning - much less morals- in children's literature led to the creation of a new genre of children's poetry: nonsense verse, whimsical poetry that focuses more on sound than sense. Although nonsense verse existed for most of human history- many nursery rhymes and traditional folk songs qualify- it was rare to see original nonsense verse in print until the 1800s.

One of the first modern poets to write nonsense verse was Edward Lear - his limericks focus on absurd, whimsical situations, and his later poetry revels in made-up words and ridiculous concepts. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature says, "Only an age ready to be childish after having learnt the hopelessness of tacking morals on to fairy tales could have welcomed Lear’s Book of Nonsense."[4] Lear's most notable poems include The Jumblies, The Owl and the Pussy-Cat , and The Pobble Who Has No Toes.

Lewis Carroll, author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, also is well-known for writing nonsense verse. His parodies of famous children's poetry, such as How Doth the Little Crocodile, shine an amusing light on Victorian children's moral lessons. His other nonsense poems, such as Jabberwocky and The Hunting of the Snark, play with form, language, rhythm, and sound. The nonsense poetry in Alice has influenced many poets since, including surrealists and the Russian Futurists.[12]

The nineteenth century also saw the rise of the children's poet-illustrator. Kate Greenaway was one of the first children's poets to also illustrate her own work. Her publisher used an expensive and experimental process to print her illustrations, making them cutting-edge for their day. Her poetry book Under the Window initially sold 70,000 copies, and was met with great success in Europe and America as well as in the UK. She also illustrated children's poetry by Robert Browning, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Ann and Jane Taylor. While her poetry has been called "innocuous, ordinary, and of no significance away from the pictures", her work as an illustrator is massively significant, to the point where the UK's most prestigious award for children's illustration is named after her.[13]

At the turn of the century, Rudyard Kipling wrote a number of notable poems for children. Most of them are contained in the Jungle Book or in the Just So Stories, an anthology of stories that Kipling wrote for his daughter Effie.[14]

Importance[]

Introducing poetry to children helps develop their literacy skills by developing vocabulary through rhythmic structure of the stanzas which give context to new and unknown words; phonemic awareness through pitch, voice inflection, and volume; memorization through patterns and sequences; self-expression through the creativity and emotion of the words; physical awareness of breath, movements of the mouth and other gestures as they align to the rhythm of the poetry. Scholars also see that poetry and nursery rhymes are universal throughout cultures as an oral tradition.[15]

Awards[]

Awards that are given for children's poetry:

- United States - In the United States children's poetry awards include the Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children, established in 1977, awarded annually by the National Council of Teachers of English[16] and the position of Young People's Poet Laureate, a two-year appointment awarded by the Poetry Foundation to an author of children's poetry.[17]

- United Kingdom - In the United Kingdom the Poetry for Children: Signal Award was published in the journal, Signal: Approaches to Children's Books, from 1979-2001.[18][19] The Centre for Literacy in Primary Education also annually awards the Centre for Literacy in Primary Poetry Award, established in 2003.[20]

- North America - The Lion and The Unicorn Award for Excellence in North American Poetry, established in 2005, is annually awarded by the Johns Hopkins University Press.[21]

Notable children's poets[]

This article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

- Allan Ahlberg (b.1938) is one of Britain's best-loved children's writers. The author of over a hundred books.

- Francisco X. Alarcón (1954–2016) first started writing poetry for children in 1997 after realizing there were very few books written by Latino authors. His poems are minimalist and airy, and often published in bilingual editions.[22]

- Valerie Bloom (b.1956) is a Jamaican-born poet and a novelist based in the UK.

- Roald Dahl (1916–1990) is one of the most successful children's writers in the world: around thirty million of his books have been sold in the UK alone. Dahl's collection of poems Revolting Rhymes is a re-interpretation of six well-known fairy tales, featuring surprise endings in place of the traditional happily-ever-after.[23] Dahl's poems and stories are popular among Children because he writes from their point of view - in his books adults are often the villains or are just plain stupid![23]

- Paul Fleischman (b.1952) is best known for his collection Joyful Noise: Poems for Two Voices, winner of the 1989 Newbery Medal.[22]

- Nikki Giovanni (b. 1943) is one of the world's most well-known African-American poets. Her work directly addresses the African American experience in Spin a Soft Black Song and others.[22]

- Charles Lamb (1775–1834), best known for his Essays of Elia and for the children's book Tales from Shakespeare, co-authored with his sister, Mary Lamb (1764–1847).

- Edward Lear (1812–1888) was the first to use limericks in his writing, authoring A Book of Nonsense in 1846 and featuring silly poetry and neologisms.[22]

- Brian Moses (b.1950) is one of Britain's favourite children's poets, for both his own poetry and the anthologies he has edited, and he has performed in over two thousand schools across the UK and Europe. He is a Reading Champion for the Literacy Trust.

- Jack Prelutsky (b.1940) - Author of such works as , Jack Prelutsky was selected the inaugural Young People's Poet Laureate by the Poetry Foundation in 2006.

- Michael Rosen is a broadcaster, children's novelist and poet and the author of 140 books. He was appointed as the fifth Children's Laureate in June 2007, succeeding Jacqueline Wilson, and held this honor till 2009.

- Dr. Seuss - wrote many Children's poetry books including The Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, and How the Grinch Stole Christmas!.

- Shel Silverstein - author of such works as Where the Sidewalk Ends and A Light in the Attic, Silverstein also wrote The Giving Tree.[22]

- Jean Sprackland (b.1962), is an English poet, the author of three collections of poetry published since 1997.

- Robert Louis Stevenson - author of such works as A Child's Garden of Verses.[22]

- Jane Taylor (poet) (1783–1824) co-wrote the ubiquitous Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star with her sister.

- Judith Viorst (b. 1931) is known for her humorous observational poetry and for her children's literature.[22]

- Gez Walsh is a performance poet and stand-up comedian best known as the author of the cult classic children's poetry book The Spot on my Bum.

- Jacqueline Woodson (b. 1963), writer of Newbery Honor-winning Brown Girl Dreaming, an adolescent novel told in verse.[22]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Ntuli, Cynthia Danisile Daphne (20 December 2013). "Children's oral poetry: A reflection on the role of Imilolozelo (lullabies) as Art Performance in Zulu". Muziki. 10 (sup1): 13–23. doi:10.1080/18125980.2013.852739. ISSN 1812-5980. S2CID 192177851. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ "The Evolution of Children's Stories". www.mykabook.com. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dixon, Ann (20 July 2007). "Poetry in children's literature: development of a genre". Library Student Journal. ISSN 1931-6100. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ward, Adolphus William; Trent, William Peterfield (1907–21). The Cambridge History of English and American Literature: An Encyclopedia in Eighteen Volumes, Volume 11 (bartleby.com ed.). ISBN 1-58734-073-9. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Cotton, John, BD; Royster, Paul (1646). Milk for Babes. Drawn Out of the Breasts of Both Testaments. Chiefly, for the Spirituall Nourishment of Chiefly, for the Spirituall Nourishment of BostonBoston Babes in Either Babes in Either EnglandEngland: But May Be of Like Use for Any Children (1646) : But May Be of Like Use for Any Children. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Nikolajeva, María, ed. (1995). Aspects and Issues in the History of Children's Literature. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-29614-7.

- ^ a b Murdoch, Lydia. "Alice and the Question of Victorian Childhood - Archives & Special Collections Library - Vassar College". specialcollections.vassar.edu. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Newbery, John (1787). A little pretty pocket-book : intended for the instruction and amusement of little Master Tommy, and pretty Miss Polly : with two letters from Jack the giant-killer, as also a ball and pincushion, the use of which will infallibly make Tommy a good boy, and Polly a good girl : to which is added, A little song-book, being a new attempt to teach children the use of the English alphabet, by way of diversion. Isaiah Thomas.

- ^ Turner, Elizabeth (1897). Mrs. Turner's Cautionary Stories. London: Grant Richards. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Glen, Emil. "Hilaire Belloc and Edward Gorey; Cautionary Tales for Children: Goreyography West Wing". www.goreyography.com. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ a b c "William Roscoe: The Butterfly's Ball, and the Grasshopper's Feast". spenserians.cath.vt.edu. Virginia Tech. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Firtich, Nikolai. "WORLDBACKWARDS: Lewis Carroll, Nonsense and Russian Avant-Garde - Archives & Special Collections Library - Vassar College". www.vassar.edu. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "History of the Medals – The CILIP Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Children's Book Awards". carnegiegreenaway.org.uk. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Karlin, Daniel (23 December 2015). "Kipling and the origins of the 'Just-So' stories". OUPblog. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "5 Benefits of Poetry Recitation in a Child's Literacy Development | Scholar Base". scholar-base.com. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- ^ "Children's Book and Poetry Awards". NCTE. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (2021-09-18). "Young People's Poet Laureate". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Thimble Press - Poetry". www.thimblepress.co.uk. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Announcement of New Poetry Feature". The Lion and the Unicorn. 27 (3): bmxi–bmxii. 2003. doi:10.1353/uni.2003.0029. ISSN 1080-6563.

- ^ "CLiPPA - The CLPE Poetry Award | Centre for Literacy in Primary Education". clpe.org.uk. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ "Blackaby wins The Lion and The Unicorn Poetry Award" (PDF). The Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h "10 Wonderful Children's Poets You Should Know". Literary Hub. 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- ^ a b Once upon a time, there was a man who liked to make up stories ... The Independent (Sunday, 12 December 2010)

Further reading[]

- Brewton, John Edmund. Index to Poetry for Children and Young People, 1964–1969. New York: Wilson, 1972.

- Index to Poetry for Children and Young People, 1976–1981. New York: Wilson, 1981.

- Sell, Violet, Dorothy B. Frizzell Smith, Ardis Sarff O’Hoyt, and Mildred Bakke. Subject Index to Poetry for Children and Young People. Chicago: American Library Association, 1957, ISBN 0-8389-0242-1.

- Children's poetry

- Genres of poetry

- Children's literature