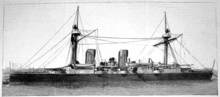

Chilean cruiser Esmeralda (1883)

Illustration of Esmeralda by Norman Davis for the Illustrated London News, 1891

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Esmeralda |

| Namesake | Chilean corvette Esmeralda[1] |

| Builder | Armstrong Mitchell, Elswick, United Kingdom |

| Yard number | 429 |

| Laid down | 5 April 1881 |

| Launched | 6 June 1883 |

| Completed | 15 July 1884 |

| Commissioned | 16 October 1884 |

| Fate | Sold to Japan, 1894 |

| Renamed | Izumi |

| Namesake | Izumi Province |

| Stricken | 1 April 1912 |

| Fate | Scrapped |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement | 2,950 long tons (2,997 t) |

| Length | 270 ft (82 m) (pp) |

| Beam | 42 ft (13 m) |

| Draft | 18 ft 6 in (6 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 18.3 knots (33.9 km/h; 21.1 mph) |

| Complement | 296 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | Up to 1 in (25 mm) |

The Chilean cruiser Esmeralda was the first protected cruiser, a ship type named for the arched that protected its most vital areas, including its propulsion plant and magazines.

Constructed by the British shipbuilders Armstrong Mitchell in the early 1880s, Esmeralda was hailed as "the swiftest and most powerfully armed cruiser in the world" by William Armstrong, the company's founder.[2] Esmeralda was completed in 1884, and the ship was quickly deployed to Panama in the following year to show the Chilean flag and conduct gunboat diplomacy during an emerging crisis in the region. The cruiser was later used to support the Congressionalist cause during the 1891 Chilean Civil War.

In 1894, Esmeralda was sold to Japan via Ecuador. Renamed Izumi,[A] the cruiser did not participate in the major naval battles of the First Sino-Japanese War, but saw active service during the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. In the latter, Izumi was one of the first ships to make visual contact with the Russian fleet just before the decisive Battle of Tsushima. After the conflict, the aging cruiser was decommissioned and stricken from the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1912.

Design[]

Background[]

Esmeralda was designed and constructed in an era of rapidly advancing naval technology, and it is today recognized as the first protected cruiser, a ship type characterized by the armored deck that protected vital machinery. Cruisers prior to Esmeralda were often constructed of primarily wood and nearly all still carried the masts and rigging required for sailing; Esmeralda built out of steel, with no wood, and carried no equipment for sailing.[4]

The rise of protected cruisers echoed that of the French Jeune École naval theory, which catered to nations in a position of naval inferiority.[5] As historian Arne Røksund has said, "one of the fundamental ideas in the Jeune École's naval theory [was] that the weaker side should resort to alternative strategies and tactics, taking advantage of the possibilities opened up by technological progress."[6] To accomplish this, Jeune École adherents called for the construction of small, steam-powered, heavy-gunned, long-ranged, and higher-speed warships to counter the capital ship-heavy strategy of major navies and devastate their merchant shipping.[5]

Within the Chilean context, Esmeralda was ordered in the midst of the War of the Pacific (1879–1884), fought between Chile and an alliance of Bolivia and Peru. As control of the sea would likely determine the victor, both sides rushed to acquire warships in Europe despite the determinations of Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, the Ottoman Empire, and the United Kingdom to remain neutral in the conflict. Esmeralda was one of these ships, albeit the most capable, and it was ordered with the intention of giving Chile naval superiority over its neighbors.[7][8]

It was designed by the British naval architect George Wightwick Rendel, who developed it from the Japanese cruiser Tsukushi. This ship was constructed by the British shipbuilder Armstrong at its Elswick works. Carrying the preliminary name Arturo Prat, it was originally destined for Chile, but due to the effective end of the War of the Pacific, it was sold to Japan.[8][9]

Public reaction[]

As the world's first protected cruiser, Esmeralda's construction attracted much publicity. A warship with a "truly modern appearance," according to a later naval historian,[10] its capabilities were highly anticipated within Chile: it was financed in part by public donations and the country's newspapers published lengthy treatises on the cruiser's potential power.[7]

William Armstrong, Armstrong's founder, was keen to promote his company's newest warship to increase sales. He boasted to press outlets in 1884 that Esmeralda was "the swiftest and most powerfully armed cruiser in the world" and that it was "almost absolutely secure from the worst effects of projectiles."[2][11] He believed that the protected cruiser warship type, exemplified by Esmeralda, would usher in the end of the ironclad era. For the price of one ironclad, several cruisers could be built and sent out as commerce raiders, much like the Confederate Alabama during the United States' civil war.[12] This argument closely mirrored the emerging Jeune École school of French naval thought, and protected cruisers like Esmeralda were hailed by Jeune École adherents as "the battleship of the future."[13]

In addition, Armstrong pointedly noted that it was fortunate that Chile had purchased the ship rather than a country that might become hostile with the United Kingdom; with this comment, he hoped to push the Royal Navy to order protected cruisers from his company lest he sell them to British enemies instead.[2][11][12] His remarks were later summarized in press outlets like of Valparaiso:

Happily ... she had passed into the hands of a nation which is never likely to be at war with England, for he could conceive no more terrible scourge for our commerce than she would be in the hands of an enemy. No cruiser in the British navy was swift enough to catch her or strong enough to take her. We have seen what the Alabama could do ... what might we expect from such an incomparably superior vessel as the Esmeralda[?][2]

His company's efforts to publicize Esmeralda included a weighty article in the Times of London, written anonymously by Armstrong's chief naval architect.[14][15] Unusually, the Prince of Wales and future King Edward VII visited the ship.[14] This promotion was quite successful: by the time Esmeralda was completed in 1884, Armstrong had or would soon be constructing protected cruisers for over a dozen countries.[11] Nathaniel Barnaby, a Director of Naval Construction at the British Admiralty, the department in charge of Britain's Royal Navy, would later write that Esmeralda and the ship type it pioneered "made the fortune" of Armstrong's company and was a major factor in the widespread abandonment of sails in the world's navies.[14][16]

Across the Atlantic, the Army and Navy Journal published an interview with an American naval officer who expressed his belief that Esmeralda could stand off San Francisco and drop shells into the city while being in no danger from the shorter-ranged shore-based batteries covering the Golden Gate strait. "Chili [sic] has today the finest, fastest, and most perfectly equipped fighting war ship of her size afloat," he said. "She could destroy our entire Navy, ship by ship, and never be touched."[17] This perspective was part of a larger effort to draw attention to the underfunded and under-equipped state of the United States Navy.[18]

Analysis and criticism[]

Like the Tsukushi design that preceded it, Esmeralda mounted a heavy armament and was constructed out of lightweight steel, a feature enabled by the Siemens process.[14][19] Unlike the earlier ship, though, Esmeralda was far larger and had much more seaworthy design, including a freeboard that was 5 feet (1.5 m) higher.[14] It was also the fastest cruiser in the world upon its completion; had a better secondary armament; was able to steam longer distances before needing additional coal; and had deck armor that extended the length of the ship, with particular attention paid to the areas above the propulsion machinery and other important areas of the ship.[14][20][21] Esmeralda also favorably compared to the British Comus-class corvette and the American cruisers Atlanta and Boston.[22][23]

Still, Esmeralda's design was the target of strong criticism from the Admiralty, the British department in charge of the Royal Navy, especially in comparison to their contemporary British designs like the Mersey class.[24] The Chilean ship's freeboard was higher than Armstrong's previous design, but it was still a mere 10 feet 9 inches (3.28 m) from the waterline. It also lacked a double bottom, a proper conning tower, and any provision for emergency steering should the primary steering position be destroyed in battle. Moreover, the design of Esmeralda's coal bunkers meant that if it was hit in certain key areas, water would be able to flow into a good portion of the ship.[25] Finally, an Admiralty comparison of Esmeralda to the Mersey design found that the former carried nearly 400 tons less armor, which measured out to about 3.5 percent of the ship's total displacement. For Mersey, the same figure came out to 12.5 percent when a full load of coal was embarked.[24]

Modern assessments have also veered toward the negative. Nearly a century after Esmeralda was completed, naval historian Nicholas A. M. Rodger wrote that Esmeralda's design suffered from a disconnect between what Rendel designed the ship to do, and the missions most small cruisers in the world, including Chile's, would take on in a conflict: the protection of their own maritime trade or disrupting an enemy's.[26][27] Rendel gave Esmeralda large ten-inch guns and a high speed so its captain could choose the range they wanted to fight at. In theory, this gave the cruiser the ability to destroy an enemy's most heavily armed and armored capital warships. However, the same ten-inch guns were unnecessary for facing down enemy cruisers or raiders, especially as Esmeralda's armor deck gave it a margin of safety when facing ships with smaller weapons.[28] Warship contributor Kathrin Milanovich added that the practical utility of Esmeralda's 10-inch (250 mm) guns was limited by the light build of the ship, which did not provide a stable platform when firing, and its low freeboard, which meant that the guns could be swamped in rough seas. Milanovich also pointed out the lack of a double bottom and the limited size of Esmeralda's coal bunkers.[29]

Except for the designs which immediately followed Esmeralda (the Japanese Naniwa class and the Italian Giovanni Bausan), no other Armstrong-built protected cruiser would ever mount a gun larger than 8.2 inches (210 mm).[30]

Specifications[]

Esmeralda was made entirely of steel and measured in at a length of 270 feet (82 m) between perpendiculars. It had a beam of 42 feet (13 m), a mean draft of 18 feet 6 inches (5.6 m), and displaced 2,950 long tons (3,000 t). It was designed for a crew of 296.[31]

For armament, Esmeralda's main battery was originally equipped with two 10-inch (254 mm)/30 caliber guns in two single barbettes, one each fore and aft.[31] The ten-inch weapons were able to be trained to either side of the ship, raised to an angle of 12°, and depressed to 5°. They weighed 25 tons each, while the shells they fired weighed 450 pounds (200 kg) and required a powder charge of 230 pounds (100 kg).[32] Its secondary armament consisted of six 6-inch (152 mm)/26 caliber guns in single Vavasseur central pivot mountings; two 6-pounder guns located on the bridge wings; and five 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolving cannons located in elevated positions.[33][31] The ship was additionally fitted for but not with three 14-inch (360 mm) torpedo tubes.[32]

The propulsion machinery consisted of two horizontal compound steam engines built by R and W Hawthorn, which were fed by four double-ended fire-tube boilers. The engines were placed in separate compartments. On Esmeralda's sea trials, its machinery proved good for 6,803 indicated horsepower (5,070 kW), making a speed of 18.3 knots (34 km/h; 21 mph). The ship usually carried up to 400 long tons (410 t) of coal, but a maximum of 600 long tons (610 t) could be carried if necessary.[32] Notably, the ship was not equipped with sailing rigging.[10]

To protect itself, Esmeralda had an arched protective deck below the waterline that ran from bow to stern; it was 1 inch (25 mm) over the important machinery, and .5 inches (13 mm) near the ends of the ship. It also had cork mounted along the waterline with the intention of limiting flooding and increasing buoyancy in the case of shell penetration, but the cork's practicality was limited. The ship's coal bunkers were also designed to be part of the protective scheme, but as they were not subdivided, their utility if damaged in battle were also severely questionable. The ship's main guns were provided with shields up to 2 inches (51 mm) thick, and the conning tower was provided with its own 1-inch armor.[33][B]

While in Japanese service, Esmeralda was renamed Izumi and fitted with two 6-inch (152 mm)/40 caliber quick-firing guns (in 1901–02), six 4.7-inch (120 mm)/40 caliber quick-firing guns (in 1899), several smaller guns, and three 18-inch (460 mm) torpedo tubes. These changes lightened the ship, making for a displacement of 2,800 long tons (2,845 t) even while its machinery could still manage 6,500 ihp (4,800 kW).[34][35]

Chilean service[]

Armstrong Mitchell laid Esmeralda's keel down on 5 April 1881 in Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne. They gave it the yard number 429.[16][32] The completed hull was launched on 6 June 1883, and the ship was completed on 15 July 1884, making for a construction time of just over three years.[32] While the British government upheld its neutrality through the active prevention of warship deliveries to the countries involved in the War of the Pacific, Esmeralda was finished after the conclusion of the conflict and arrived in Chile on 16 October 1884.[7][21] Nevertheless, with the United States having neglected their navy since the end of their civil war, Esmeralda allowed Chile to lay claim to possessing the most powerful navy in the Americas: their fleet was centered around the protected cruiser, two well-maintained 1870s central-battery ironclads and two 1860s armored frigates. Moreover, they could staff them with foreign-trained officers and highly trained and disciplined sailors.[36][37]

Esmeralda arrived in Chile in October 1884.[38] In the following April, the Chilean government sent the ship on an unusual and statement-making voyage to Panama, where it showed the Chilean flag alongside the great powers of France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[39] The ship was able to complete the run north in 108 hours, or about four and a half days, maintaining a high average speed of 12.6 knots (23.3 km/h; 14.5 mph) for the first hundred of those hours.[40] At least one historian has stated that Esmeralda was ordered to block an annexation of Panama by the United States, which had sent marines and several warships to the area,[41] but another has argued that the various sources of information about the incident are contradictory and do not agree with that interpretation.[39]

Chilean Civil War[]

During the 1891 Chilean Civil War, Esmeralda and most of the Chilean Navy supported the victorious Congressionalist rebels over the rival Presidential-led faction.[34] Esmeralda's commander Policarpo Toro refused to join the Congressionalists and was therefore replaced by Pedro Martínez.[42]

In the first days of the war, Esmeralda steamed to the port of Talcahuano in search of money and weapons. It then went further south to intercept the corvette Abtao and the two Almirante Lynch class torpedo gunboats coming from Europe to Chile. She did not find them, although Abtao would later join the rebels.[43]

Later, Esmeralda left for the north of the country to participate with the rest of the Congressionalist squadron in blockading and controlling the ports in the area. On 19 February, during the final phase of naval operations in the north, she participated in the . Congressionalist troops, outnumbered, managed to retain that strategic port with the decisive support of the squadron, which bombarded the positions of the Presidential troops until they finally capitulated.[44][45]

On 12 March, Esmeralda engaged in a prolonged chase with the steamer Imperial, an elusive transport ship that had a reputation for being the fastest on the coast, and had on occasion managed to bring reinforcements north for the Presidential cause.[46][47] The engagement began in the early morning of that day in front of Antofagasta and lasted until night. Although Esmeralda was able to get close enough to fire shots at Imperial, the cruiser was unable to reach its maximum speed due to dirty boilers and therefore lost track of the transport that night.[48]

One month later, the ship escorted the Congressionalist cargo ship Itata north to the United States so that it could take on a load of rifles, although to allay suspicion the two vessels parted ways off the coast of Mexico. In what would become known as the Itata incident, the cargo ship was detained to uphold American neutrality in Chile's civil war but escaped. The US cruiser Charleston was sent to hunt the cargo ship down, and press outlets published their opinions on whether Esmeralda or Charleston would prevail if it came to single combat. Although the two warships did meet in Acapulco, Mexico, no violence broke out. Itata reached Chile without incident but was returned to San Diego with the acquiescence of the Congressionalists.[49]

In August, Esmeralda participated in the last naval operations of the war by supporting the landing of Congressionalist troops at Quintero Bay. On the 17th, she steamed near Valparaíso and fired three shots to alert the Presidential forces of the arrival of the Congressionalists.[50] On the 21st, Esmeralda with the corvettes O'Higgins and Magallanes engaged the Presidential ground forces during the Battle of Concón from the mouth of the Aconcagua River. Their gunfire did not kill many soldiers, but it severely demoralized the Presidential forces; Scientific American stated that their shells "raised fearful havoc".[51][52] Finally on the 22nd, Esmeralda attacked the forts of Viña del Mar together with the ironclad Almirante Cochrane, with a successful result.[53]

Transfer to Japan and Ecuadorian ramifications[]

After the conflict, the Chilean Navy briefly considered modernizing Esmeralda in March 1894 amidst the quickly escalating Argentine–Chilean naval arms race. These efforts went as far as asking Armstrong to furnish plans for upgrading the ship's weapons, replacing its propulsion machinery, adding superstructure, and more. However, in November 1894 they instead sold the ship to the Imperial Japanese Navy, likely in an effort to raise the funds for a new armored cruiser.[34][54][C] Japan bought Esmeralda for ¥3.3 million, using about a third of the funds that the Japanese Cabinet and Parliament had originally earmarked for the purchase of three Argentine warships.[55]

However, at this time the Japanese were engaged in the First Sino-Japanese War and the Chilean government wanted to remain neutral in the conflict. To achieve this, the Chileans induced Ecuador's President Luis Cordero Crespo to serve as an intermediary: Esmeralda would first be sold and sailed to Ecuador, whose navy would briefly take formal possession of the ship so that it, not Chile, would be the one to sell it to Japan.[34] This arrangement would later become known as the "," and was facilitated with a considerable payment to the Ecuadorian president.[56][57]

Although there was some speculation in press outlets that Esmeralda would join the Ecuadorian Navy for potential use against the Peruvian Navy, the ship was only under the Ecuadorian flag from Chile to the Galapagos Islands, where it was handed to the Japanese. Back in Ecuador, Cordero's political opponents seized upon the incident and kicked off the successful Liberal Revolution.[58][59][60]

Japanese service[]

Although the Japanese purchased Esmeralda with the intention of using it in the First Sino-Japanese War, the cruiser arrived in Japan in February 1895—too late to take an active role in the conflict.[34][61] Renamed Izumi, the Japanese Navy employed it in the post-war invasion of Taiwan later that year.[62] In 1899, the Japanese replaced the ship's secondary armament with quick-firing 4.7-inch guns and removed the ship's fighting tops to improve its stability. Two years later, Izumi's ten-inch guns were removed in favor of quick-firing 6-inch weapons.[34] In between the modifications, it remained on active duty with the standing naval squadron and took part in what the US Office of Naval Intelligence called "by far the most comprehensive" naval training exercise ever conducted by Japan up to that point. Deployed alongside much of the rest of the Japanese Navy, Izumi was assigned to a green water blocking squadron and a blue water attacking fleet.[63]

Japan went to war again in 1904, this time against Russia. After the Japanese cruiser Akashi struck a mine in December 1904, Izumi was deployed on a patrol line south of Dalian Bay. Later that month, with the Japanese aware of the approaching Russian Baltic Fleet, Izumi was sent back to Japan for minor repairs so that it would be fit for service in the coming Battle of Tsushima. When the Japanese Navy deployed to engage the Russian ships, Izumi was one of four cruisers to make up the Sixth Division within the Third Squadron, under the commands of Rear Admiral and Vice Admiral Kataoka Shichirō (respectively).[64]

Prior to the battle, Izumi was assigned to support a line of auxiliary cruisers stationed in the Tsushima Strait. These ships were charged with spotting the Russian fleet so its Japanese counterpart could move into position to engage. However, this line was later described by historian Julian Corbett as "ill-covered," and Izumi compounded the issue by being 8–9 miles (13–14 km) out of position on the morning of the battle (27 May 1905). Moreover, it had trouble finding the Russians after investigating erroneously located spotting reports radioed in by the auxiliary Shinano Maru at 4:45 am.[65]

Around 6:30 or 6:40 am, Izumi finally made visual contact with the opposing Russian fleet; it was the first proper warship to do so. Correcting the previously mistaken spotting, Izumi shadowed the opposing warships for several hours, correctly identifying the lead Russian flagship as a cruiser of the Izumrud class, and reported their movements back to the main Japanese fleet.[66][67][68] Izumi also warned off an army hospital ship and troop transport in the area so that they were not caught by the Russians.[69]

When the two fleets drew near for battle, Izumi was forced to turn away from heavy fire at around 1:50 pm; the change in course allowed it to cut off two of the Russian fleet's hospital ships, which were later captured by two of the Japanese auxiliary cruisers.[70] Later in the battle, after the Japanese main battle line had 'crossed the T' of the Russian fleet and forced it to turn around, Izumi and several other lighter ships from various Japanese squadrons were caught in close proximity to heavy Russian ships. Izumi, however, escaped with minimal damage, in part due to the intervention of the Japanese battleships of the Second Squadron.[71]

After the battle, Izumi and the rest of the Sixth Division were deployed to support the invasion of Sakhalin by escorting the army's transport ships.[72]

With the conclusion of the war in September 1905, the aging Izumi was utilized for auxiliary tasks for several years.[66] For example, the reported in February 1906 that the ship was to transport the former Prime Minister of Japan and the first Japanese Resident-General of Korea Itō Hirobumi to his post.[73] On 1 April 1912, Izumi was struck from Japan's navy list.[66] It was later sold for scrapping in Yokosuka for ¥90,975.[74][75]

Footnotes[]

Endnotes[]

- ^ Vio Valdivieso, Reseña historica, 96.

- ^ a b c d "The 'Esmeralda,'" Record (Valparaiso) 13, no. 183 (4 December 1884): 5.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 465.

- ^ Sondhaus, Naval Warfare, 139–141.

- ^ a b Sondhaus, Naval Warfare, 139–140.

- ^ Røksund, Jeune École, x.

- ^ a b c Grant, Rulers, 122.

- ^ a b Sondhaus, Naval Warfare, 132.

- ^ Gardiner, Chesneau, and Kolesnik, eds., Conway's, 233.

- ^ a b Sondhaus, Naval Warfare, 140.

- ^ a b c Bastable, Arms and the State, 176.

- ^ a b "Home," Graphic 30, no. 775 (4 October 1884): 347.

- ^ Sondhaus, Naval Warfare, 141.

- ^ a b c d e f Brook, Warships for Export, 53.

- ^ "Protected Cruisers," Times (London), 6 August 1884, 2a–c – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ a b Brook, "The Elswick Cruisers: Part I," 159.

- ^ "We Cannot Fight the Chilean Navy," Army and Navy Journal 23, no. 1 (1 August 1885): 16.

- ^ Sater, Chile and the United States, 51–52.

- ^ Brook, "Armstrongs and the Italian Navy," 94.

- ^ Perrett, "Some Notes," 211.

- ^ a b Crucero "Esmeralda" 3°, Armada de Chile. Accessed 9 June 2020.

- ^ Rodger, "The First Light Cruisers," 219–220.

- ^ "The New Cruisers," The New York Times, 10 December 1884, 4.

- ^ a b Brook, Warships for Export, 54–55.

- ^ Brook, Warships for Export, 54.

- ^ Rodger, "The First Light Cruisers," 214, 220.

- ^ Brook, Warships for Export, 62.

- ^ Rodger, "The First Light Cruisers," 214, 220–221.

- ^ Milanovich, "Naniwa and Takachiho," 31.

- ^ Brook, Warships for Export, 58 and 62.

- ^ a b c d Gardiner, Chesneau, and Kolesnik, eds., Conway's, 411.

- ^ a b c d e Brook, Warships for Export, 52.

- ^ a b Brook, Warships for Export, 52–53.

- ^ a b c d e f Brook, Warships for Export, 55.

- ^ Jentschura, Jung, and Mickel, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 98–99.

- ^ Grant, Rulers, 121–123.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America, 43–46.

- ^ "[Untitled]," Record (Valparaiso) 13, no. 180 (22 October 1884): 3.

- ^ a b Tromben, "Naval Presence," n.p.

- ^ Bainbridge-Hoff, Examples, 121.

- ^ Sater, Chile and the United States, 52.

- ^ Fuenzalida Bade, "Capitán de fragata Policarpo Toro Hurtado," 112.

- ^ Hurtado, "Resumen," 48.

- ^ Hurtado, "Resumen," 50.

- ^ López Urrutia, Historia de la Marina, 439–440.

- ^ Hurtado, "Resumen," 50–51.

- ^ López Urrutia, Historia de la Marina, 440.

- ^ López Urrutia, Historia de la Marina, 440–441.

- ^ Hardy, "The Itata Incident," 195–225.

- ^ Hurtado, "Resumen," 56.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars, 1:402.

- ^ "The Recent Battles in Chile," Scientific American, 13240.

- ^ López Urrutia, Historia de la Marina, 452.

- ^ a b Scheina, Naval History, 48.

- ^ Schencking, Making Waves, 83n9.

- ^ Maren Goldberg, "Esmeralda Affair," Encyclopaedia Britannica, last modified 6 August 2009.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars, 1:146.

- ^ Lauderbaugh, History of Ecuador, 79–80.

- ^ "Ecuador Buys a Cruiser," New York Times, 2 December 1894, 9.

- ^ "Speculations About the Sale; The Esmeralda Could Easily Be Transferred from Ecuador to Japan," New York Times, 3 December 1894, 5.

- ^ Office of Naval Intelligence, General Information Series, 14:49.

- ^ Van Duzer, "Naval Progress," 178.

- ^ Office of Naval Intelligence, General Information Series, 20:397–408.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 110, 130, 216.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 221—223.

- ^ a b c Brook, Warships for Export, 56.

- ^ Pleshakov, The Tsar's Last Armada, 262–263.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 226.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 235.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 273–274.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 278–279.

- ^ Corbett, Maritime Operations, 356–357, 365.

- ^ "Korea," Japan Weekly Mail, 10 February 1906, 143.

- ^ Jentschura, Jung, and Mickel, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 99.

- ^ "Local and General," The Japan Chronicle, 30 January 1913, 180.

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Esmeralda (ship, 1884). |

- Bainbridge-Hoff, W.M. Examples, Conclusions, and Maxims of Modern Naval Tactics. General Information Series, no. 3. Washington, D.C.: Office of Naval Intelligence, Bureau of Navigation, US Naval Department, 1884.

- Bastable, Marshall J. Arms and the State: Sir William Armstrong and the Remaking of British Naval Power, 1854–1914. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2004.

- Brook, Peter. "Armstrongs and the Italian Navy." In Warship 2002–2003, edited by Antony Preston, 94–115. London: Conway Maritime Press, 2003.

- ———. "The Elswick Cruisers: Part I, The Early Types." Warship International VII, no. 2 (30 June 1970): 154–176.

- ———. Warships for Export: Armstrong Warships, 1867–1927. Gravesend, UK: World Ship Society, 1999.

- Corbett, Julian S. Maritime Operations in the Russo–Japanese War, 1904—1905. Volume 2. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994. First published in 1915.

- "Crucero 'Esmeralda' 3° [Cruiser 'Esmeralda' #3]," Unidades Historicas, Armada de Chile (Chilean Navy).

- Fuenzalida Bade, Rodrigo. "Capitán de fragata Policarpo Toro Hurtado [Frigate Captain Policarpo Toro Hurtado]." Revista de Marina Journal 90, no. 692 (January–February 1973): 108–12.

- Gardiner, Robert, Roger Chesneau, and Eugene Kolesnik, eds. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979.

- Grant, Jonathan A. Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Hardy, Osgood. "The Itata Incident." The Hispanic American Historical Review 5 (1922), 195–225.

- Hurtado, Homero. "Resumen de las operaciones navales en la revolución de 1891 [Summary of naval operations in the revolution of 1891]." Revista de Marina Journal 76, no. 614 (January–February 1960).

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg, Dieter Jung, and Peter Mickel. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Translated by Antony Preston and J.D. Brown. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute, 1977.

- Lauderbaugh, George. The History of Ecuador. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2012.

- López Urrutia, Carlos. Historia de la Marina de Chile [History of the Chilean Navy]. Santiago: El Ciprés Editores, 2007.

- Office of Naval Intelligence. General Information Series: Information from Abroad. 21 vols. General Information Series. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1883–1902.

- Milanovich, Kathrin. "Naniwa and Takachiho: Elswick-built Protected Cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy". In Warship 2004, edited by Antony Preston, 29–56. London: Conway Maritime Press, 2014.

- Perrett, J.R. "Some Notes on Warships; Designed and Constructed by Sir W.G. Armstrong, Whitworth, & Co., Ltd." Mechanical Engineer 34, no. 867 (4 September 1914): 211–13.

- Pleshakov, Constantine. The Tsar's Last Armada: The Epic Journey to the Battle of Tsushima. New York: Basic Books, 2008.

- Quiñones López, Carlos. "La Tercera Esmeralda [The Third Esmeralda]." Revista de Marina Journal 106, no. 790 (May - June 1989).

- Rodger, Nicholas A. M. "The First Light Cruisers." The Mariner's Mirror 65, no. 3 (1979): 209–230. doi:10.1080/00253359.1979.10659148.

- Sater, William F. Chile and the United States: Empires in Conflict. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1990.

- Scheina, Robert. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

- Scheina, Robert. Latin America's Wars. 2 vols. Dulles, VA: Brassey's, 2003.

- Schencking, J. Charles. Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, And The Emergence Of The Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868–1922. Stanford, CA, US: Stanford University Press, 2005.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence. Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge, 2001.

- "The Recent Battles in Chile." Scientific American 32, supplement no. 829 (21 November 1891): 13240.

- Tromben, Carlos. "Presencia Naval. El Crucero 'Esmeralda' En Panamá [Naval Presence: The Cruiser Esmeralda in Panama]." International Journal of Naval History 1, no. 1 (April 2002).

- Thomas Cavieres, Federico. "Cruceros al servicio de la Armada de Chile [Cruisers in the service of the Chilean Navy]." Revista de Marina Journal 107, no. 798 (September - October 1990).

- Van Duzer, L.S. "Naval Progress in 1895." The United Service 15, no. 2 (February 1896), 167–184.

- Vio Valdivieso, Horacio. Reseña historica de los nombres de las unidades de la armada de Chile [Historical review of the names of the units of the Chilean Navy]. Santiago: Imprenta Chile, 1933.

- Cruisers of the Chilean Navy

- Cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy

- Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth

- Ships built on the River Tyne

- 1883 ships

- Naval ships of Japan

- First Sino-Japanese War cruisers of Japan

- Russo-Japanese War cruisers of Japan