Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 April 1629 The Hague, Dutch Republic |

| Died | 8 July 1695 (aged 66) The Hague, Dutch Republic |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Alma mater | University of Leiden University of Angers |

| Known for | show

List |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural Philosophy Mathematics Physics Astronomy Horology |

| Institutions | Royal Society of London French Academy of Sciences |

| Influences | Galileo Galilei René Descartes Frans van Schooten |

| Influenced | Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Isaac Newton[2][3] |

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

Christiaan Huygens FRS (/ˈhaɪɡənz/ HY-gənz,[4] also US: /ˈhɔɪɡənz/ HOY-gənz,[5][6] Dutch: [ˈkrɪstijaːn ˈɦœyɣə(n)s] (![]() listen); Latin: Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695), also spelled Huyghens, was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, astronomer and inventor, who is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists of all time and a major figure in the scientific revolution. In physics, Huygens made groundbreaking contributions in optics and mechanics, while as an astronomer he is chiefly known for his studies of the rings of Saturn and the discovery of its moon Titan. As an inventor, he improved the design of telescopes and invented the pendulum clock, a breakthrough in timekeeping and the most accurate timekeeper for almost 300 years. An exceptionally talented mathematician and physicist, Huygens was the first to idealize a physical problem by a set of parameters then analyze it mathematically (Horologium Oscillatorium),[7] and the first to fully mathematize a mechanistic explanation of unobservable physical phenomena (Traité de la Lumière).[8] For these reasons, he has been called the first theoretical physicist and one of the founders of modern mathematical physics.[9][10]

listen); Latin: Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695), also spelled Huyghens, was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, astronomer and inventor, who is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists of all time and a major figure in the scientific revolution. In physics, Huygens made groundbreaking contributions in optics and mechanics, while as an astronomer he is chiefly known for his studies of the rings of Saturn and the discovery of its moon Titan. As an inventor, he improved the design of telescopes and invented the pendulum clock, a breakthrough in timekeeping and the most accurate timekeeper for almost 300 years. An exceptionally talented mathematician and physicist, Huygens was the first to idealize a physical problem by a set of parameters then analyze it mathematically (Horologium Oscillatorium),[7] and the first to fully mathematize a mechanistic explanation of unobservable physical phenomena (Traité de la Lumière).[8] For these reasons, he has been called the first theoretical physicist and one of the founders of modern mathematical physics.[9][10]

In 1659, Huygens derived geometrically the now standard formulae in classical mechanics for the centripetal force and centrifugal force in his work De vi centrifuga.[11] Huygens also identified the correct laws of elastic collision for the first time in his work De motu corporum ex percussione, published posthumously in 1703. In the field of optics, he is best known for his wave theory of light, which he proposed in 1678 and described in his Traité de la Lumière (1690). His mathematical theory of light was initially rejected in favor of Newton's corpuscular theory of light, until Augustin-Jean Fresnel adopted Huygens's principle in 1818 to explain the rectilinear propagation and diffraction effects of light. Today this principle is known as the Huygens–Fresnel principle.

Huygens invented the pendulum clock in 1657, which he patented the same year. His research in horology resulted in an extensive analysis of the pendulum in Horologium Oscillatorium (1673), regarded as one of the most important 17th century works in mechanics. While the first part contains descriptions of clock designs, most of the book is an analysis of pendulum motion and a theory of curves. In 1655, Huygens began grinding lenses with his brother Constantijn to build telescopes for astronomical research. He was the first to identify the rings of Saturn as "a thin, flat ring, nowhere touching, and inclined to the ecliptic," and discovered the first of Saturn's moons, Titan, using a refracting telescope.[12][13] In 1662 Huygens developed what is now called the Huygenian eyepiece, a telescope with two lenses, which diminished the amount of dispersion.

As a mathematician, Huygens developed the theory of evolutes and wrote on games of chance and the problem of points in Van Rekeningh in Spelen van Gluck, which Frans van Schooten translated and published as De ratiociniis in ludo aleae (1657).[14] The use of expectation values by Huygens and others would later inspire Jacob Bernoulli's work on probability theory.[15][16]

Biography[]

Christiaan Huygens was born on 14 April 1629 in The Hague, into a rich and influential Dutch family,[17][18] the second son of Constantijn Huygens. Christiaan was named after his paternal grandfather.[19][20] His mother, Suzanna van Baerle, died shortly after giving birth to Huygens's sister.[21] The couple had five children: Constantijn (1628), Christiaan (1629), Lodewijk (1631), Philips (1632) and Suzanna (1637).[22]

Constantijn Huygens was a diplomat and advisor to the House of Orange, in addition to being a poet and a musician. He corresponded widely with intellectuals across Europe; his friends included Galileo Galilei, Marin Mersenne, and René Descartes.[23] Christiaan was educated at home until turning sixteen years old, and from a young age liked to play with miniatures of mills and other machines. His father gave him a liberal education: he studied languages, music, history, geography, mathematics, logic, and rhetoric, but also dancing, fencing and horse riding.[19][22][24]

In 1644 Huygens had as his mathematical tutor Jan Jansz Stampioen, who assigned the 15-year-old a demanding reading list on contemporary science.[25] Descartes was later impressed by his skills in geometry, as did Mersenne, who christened him "the new Archimedes."[8][18][26]

Student years[]

At sixteen years of age, Constantijn sent Huygens to study law and mathematics at Leiden University, where he studied from May 1645 to March 1647.[19] Frans van Schooten was an academic at Leiden from 1646, and became a private tutor to Huygens and his elder brother, Constantijn Jr., replacing Stampioen on the advice of Descartes.[27][28] Van Schooten brought his mathematical education up to date, in particular introducing him to the work of Viète, Descartes, and Fermat.[29]

After two years, starting in March 1647, Huygens continued his studies at the newly founded Orange College, in Breda, where his father was a curator: the change occurred because of a duel between his brother Lodewijk and another student.[30] Constantijn Huygens was closely involved in the new College, which lasted only to 1669; the rector was André Rivet.[31] Christiaan Huygens lived at the home of the jurist Johann Henryk Dauber, and had mathematics classes with the English lecturer John Pell. He completed his studies in August 1649.[19] He then had a stint as a diplomat on a mission with Henry, Duke of Nassau. It took him to Bentheim, then Flensburg. He took off for Denmark, visited Copenhagen and Helsingør, and hoped to cross the Øresund to visit Descartes in Stockholm. It was not to be.[32]

Although his father Constantijn had wished his son Christiaan to be a diplomat, circumstances kept him from becoming so. The First Stadtholderless Period that began in 1650 meant that the House of Orange was no longer in power, removing Constantijn's influence. Further, he realized that his son had no interest in such a career.[33]

Early correspondence[]

Huygens generally wrote in French or Latin.[34] While still a college student at Leiden he began a correspondence with the intelligencer Mersenne, who died quite soon afterwards in 1648.[19] Mersenne wrote to Constantijn on his son's talent for mathematics, and flatteringly compared him to Archimedes on 3 January 1647.

The letters show the early interests of Huygens in mathematics. In October 1646 there is the suspension bridge, and the demonstration that a catenary is not a parabola.[35] In 1647/8 they cover the claim of Grégoire de Saint-Vincent to squaring the circle; rectification of the ellipse; projectiles, and the vibrating string.[36] Some of Mersenne's concerns at the time, such as the cycloid (he sent Huygens Torricelli's treatise on the curve), the centre of oscillation, and the gravitational constant, were matters Huygens only took seriously towards the end of the 17th century.[37] Mersenne had also written on musical theory. Huygens preferred meantone temperament; he innovated in 31 equal temperament, which was not itself a new idea but known to Francisco de Salinas, using logarithms to investigate it further and show its close relation to the meantone system.[38]

In 1654, Huygens returned to his father's house in The Hague, and was able to devote himself entirely to research.[19] The family had another house, not far away at Hofwijck, and he spent time there during the summer. His scholarly life did not allow him to escape bouts of depression.[39]

Subsequently, Huygens developed a broad range of correspondents, though picking up the threads after 1648 was hampered by the five-year Fronde in France. Visiting Paris in 1655, Huygens called on Ismael Boulliau to introduce himself, who took him to see Claude Mylon.[40] The Parisian group of savants that had gathered around Mersenne held together into the 1650s, and Mylon, who had assumed the secretarial role, took some trouble from then on to keep Huygens in touch.[41] Through Pierre de Carcavi Huygens corresponded in 1656 with Pierre de Fermat, whom he admired greatly, though this side of idolatry. The experience was bittersweet and even puzzling, since it became clear that Fermat had dropped out of the research mainstream, and his priority claims could probably not be made good in some cases. Besides, Huygens was looking by then to apply mathematics, while Fermat's concerns ran to purer topics.[42]

Scientific debut[]

Huygens was often slow to publish his results and discoveries. In the early days his mentor Frans van Schooten was cautious for the sake of his reputation.[43] His preferred methods were those of Archimedes, Descartes, and Fermat.[29]

The first work Huygens put in print was Theoremata de quadratura (1651) in the field of quadrature. It included material discussed with Mersenne some years before, such as the fallacious nature of the squaring of the circle by Grégoire de Saint-Vincent. In De circuli magnitudine inventa (1654), Huygens approximated the center of gravity of a segment of a circle by the center of the gravity of a segment of a parabola, and thus found an approximation of the quadrature; with this he was able to refine the inequalities between the area of the circle and those of the inscribed and circumscribed polygons used in the calculations of π. The same approximation with segments of the parabola, in the case of the hyperbola, yields a quick and simple method to calculate logarithms.[44] Quadrature was a live issue in the 1650s, and through Mylon, Huygens intervened in the discussion of the mathematics of Thomas Hobbes. Persisting in trying to explain the errors Hobbes had fallen into, he made an international reputation.[45]

Huygens studied spherical lenses from a theoretical point of view in 1652–3, obtaining results that remained unknown until similar work by Isaac Barrow (1669). His aim was to understand telescopes.[46] He began grinding his own lenses in 1655, collaborating with his brother Constantijn.[47] He designed in 1662 what is now called the Huygenian eyepiece, with two lenses, as a telescope ocular.[48][49] Lenses were also a common interest through which Huygens could meet socially in the 1660s with Baruch Spinoza, who ground them professionally. They had rather different outlooks on science, Spinoza being the more committed Cartesian, and some of their discussion survives in correspondence.[50] He encountered the work of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, another lens grinder, in the field of microscopy which interested his father.[51]

Huygens gave the most coherent presentation of a mathematical approach to games of chance in De ratiociniis in ludo aleae (On Reasoning in Games of Chance).[16][52] He had been told of recent work in the field by Fermat, Blaise Pascal and Girard Desargues two years earlier, in Paris.[53] Frans van Schooten translated the original Dutch manuscript into Latin and published it in his Exercitationum mathematicarum (1657). It contains early game-theoretic ideas and deals in particular with the problem of points.[14] Huygens took as intuitive his appeals to concepts of a "fair game" and equitable contract, and used them to set up a theory of expected values.[54] In 1662 Sir Robert Moray sent Huygens John Graunt's life table, and in time Huygens and his brother Lodewijk worked on life expectancy.[55]

On 3 May 1661, Huygens observed the planet Mercury transit over the Sun, using the telescope of instrument maker Richard Reeve in London, together with astronomer Thomas Streete and Reeve.[56] Streete then debated the published record of the transit of Hevelius, a controversy mediated by Henry Oldenburg.[57] Huygens passed to Hevelius a manuscript of Jeremiah Horrocks on the transit of Venus, 1639, which thereby was printed for the first time in 1662.[58] In that year Huygens, who played the harpsichord, took an interest in music and Simon Stevin's theories on it; he showed very little concern to publish his theories on consonance, some of which were lost for centuries.[59][60] The Royal Society of London elected him a Fellow in 1663.[61]

France[]

The Montmor Academy was the form the old Mersenne circle took after the mid-1650s.[62] Huygens took part in its debates, and supported its "dissident" faction who favored experimental demonstration to curtail fruitless discussion, and opposed amateurish attitudes.[63] During 1663 he made what was his third visit to Paris; the Montmor Academy closed down, and Huygens took the chance to advocate a more Baconian program in science. In 1666 he moved to Paris on an invitation to fill a position at King Louis XIV's new French Académie des sciences.[64]

In Paris, Huygens had an important patron and correspondent in Jean-Baptiste Colbert, First Minister to Louis XIV.[65] However, his relationship with the Academy was not always easy, and in 1670 Huygens, seriously ill, chose Francis Vernon to carry out a donation of his papers to the Royal Society in London, should he die.[66] Then the Franco-Dutch War took place (1672–8). England's part in it (1672–4) is thought to have damaged his relationship with the Royal Society.[67] Robert Hooke for the Royal Society lacked the urbanity to handle the situation, in 1673.[68]

Denis Papin was assistant to Huygens from 1671.[69] One of their projects, which did not bear fruit directly, was the gunpowder engine.[70] Papin moved to England in 1678, and continued to work in this area.[71] Using the Paris Observatory (completed in 1672), Huygens made further astronomical observations. In 1678 he introduced Nicolaas Hartsoeker to French scientists such as Nicolas Malebranche and Giovanni Cassini.

While in Paris, Huygens met the young diplomat Gottfried Leibniz, there in 1672 on a vain mission to meet Arnauld de Pomponne, the French Foreign Minister. At this time Leibniz was working on a calculating machine, and he moved on to London in early 1673 with diplomats from Mainz; but from March 1673 Leibniz was tutored in mathematics by Huygens.[72] Huygens taught him analytical geometry; an extensive correspondence ensued, in which Huygens showed at first reluctance to accept the advantages of infinitesimal calculus.[73]

Final years[]

Huygens moved back to The Hague in 1681 after suffering serious depressive illness. In 1684, he published Astroscopia Compendiaria on his new tubeless aerial telescope. He attempted to return to France in 1685 but the revocation of the Edict of Nantes precluded this move. His father died in 1687, and he inherited Hofwijck, which he made his home the following year.[33]

On his third visit to England, in 1689, Huygens met Isaac Newton in person on 12 June. They spoke about Iceland spar, and subsequently corresponded about resisted motion.[74]

Huygens observed the acoustical phenomenon now known as flanging in 1693.[75] Two years later, on 8 July 1695, Huygens died in The Hague and was buried in an unmarked grave in the Grote Kerk there, as was his father before him.[76]

Huygens never married.[77]

Natural Philosophy[]

Huygens was the leading European natural philosopher between Descartes and Newton.[19][78] However, unlike many of his contemporaries, Huygens had no taste for grand theoretical or philosophical systems, and generally avoided dealing with metaphysical issues (if pressed, he adhered to the Cartesian and mechanical philosophy of his time).[9][79] Instead, Huygens excelled in extending the work of his predecessors, such as Galileo, to derive solutions to unsolved physical problems that were amenable to mathematical analysis. In particular, he sought explanations that relied on contact between bodies and avoided action at a distance.[19][80]

In common with Robert Boyle and Jacques Rohault, Huygens advocated an experimentally oriented, corpuscular-mechanical natural philosophy during his Paris years. In the analysis of the Scientific Revolution, this approach was sometimes labeled "Baconian," without being inductivist or identifying with the views of Francis Bacon in a simple-minded way.[81]

After his first visit to England in 1661 and attending a meeting at Gresham College where he learned directly about Boyle's air pump experiments, Huygens spent time in late 1661 and early 1662 replicating the work. It proved a long process, brought to the surface an experimental issue ("anomalous suspension") and the theoretical issue of horror vacui, and ended in July 1663 as Huygens became a Fellow of the Royal Society. It has been said that Huygens finally accepted Boyle's view of the void, as against the Cartesian denial of it;[82] and also (in Leviathan and the Air Pump) that the replication of results trailed off messily.[83]

Newton's influence on John Locke was mediated by Huygens, who assured Locke that Newton's mathematics was sound, leading to Locke's acceptance of a corpuscular-mechanical physics.[84]

Laws of motion, impact, and gravitation[]

The general approach of the mechanical philosophers was to postulate theories of the kind now called "contact action." Huygens adopted this method, but not without seeing its difficulties and failures.[85] Leibniz, his student in Paris, later abandoned the theory.[86] Seeing the universe this way made the theory of collisions central to physics. Matter in motion made up the universe, and only explanations in those terms could be truly intelligible. While he was influenced by the Cartesian approach, he was less doctrinaire.[87] He studied elastic collisions in the 1650s but delayed publication for over a decade.[29]

Huygens concluded quite early that Descartes's laws for the elastic collision of two bodies must be wrong, and he formulated the correct laws.[88] An important step was his recognition of the Galilean invariance of the problems.[89] His views then took many years to be circulated. He passed them on in person to William Brouncker and Christopher Wren in London, in 1661.[90] What Spinoza wrote to Henry Oldenburg about them, in 1666 which was during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, was guarded.[91] Huygens had actually worked them out in a manuscript De motu corporum ex percussione in the period 1652–6. The war ended in 1667, and Huygens announced his results to the Royal Society in 1668. He published them in the Journal des sçavans in 1669.[29]

Huygens stated what is now known as the second of Newton's laws of motion in a quadratic form.[92] In 1659 he derived the now standard formula for the centripetal force, exerted on an object describing a circular motion, for instance by the string to which it is attached. In modern notation:

with m the mass of the object, v the velocity and r the radius. The publication of the general formula for this force in 1673 was a significant step in studying orbits in astronomy. It enabled the transition from Kepler's third law of planetary motion, to the inverse square law of gravitation.[93] The interpretation of Newton's work on gravitation by Huygens differed, however, from that of Newtonians such as Roger Cotes; he did not insist on the a priori attitude of Descartes, but neither would he accept aspects of gravitational attractions that were not attributable in principle to contact of particles.[94]

The approach used by Huygens also missed some central notions of mathematical physics, which were not lost on others. His work on pendulums came very close to the theory of simple harmonic motion; but the topic was covered fully for the first time by Newton, in Book II of his Principia Mathematica (1687).[95] In 1678 Leibniz picked out of Huygens's work on collisions the idea of conservation law that Huygens had left implicit.[96]

Horology[]

Huygens developed the oscillating timekeeping mechanisms that have been used ever since in mechanical watches and clocks, the balance spring and the pendulum, leading to a great increase in timekeeping accuracy. In 1656, inspired by earlier research into pendulums by figures such as Galileo, he invented the pendulum clock, which was a breakthrough in timekeeping and became the most accurate timekeeper for the next 275 years until the 1930s.[99] Huygens contracted the construction of his clock designs to Salomon Coster in The Hague, who built the clock. The pendulum clock was much more accurate than the existing verge and foliot clocks and was immediately popular, quickly spreading over Europe. However, Huygens did not make much money from his invention. Pierre Séguier refused him any French rights, while Simon Douw in Rotterdam and Ahasuerus Fromanteel in London copied his design in 1658.[100] The oldest known Huygens-style pendulum clock is dated 1657 and can be seen at the Museum Boerhaave in Leiden.[101][102][103][104]

Part of the incentive for inventing the pendulum clock was to create an accurate marine chronometer that could be used to find longitude by celestial navigation during sea voyages. However, the clock proved unsuccessful as a marine timekeeper because the rocking motion of the ship disturbed the motion of the pendulum. In 1660, Lodewijk Huygens made a trial on a voyage to Spain, and reported that heavy weather made the clock useless. Alexander Bruce elbowed into the field in 1662, and Huygens called in Sir Robert Moray and the Royal Society to mediate and preserve some of his rights.[105] Trials continued into the 1660s, the best news coming from a Royal Navy captain Robert Holmes operating against the Dutch possessions in 1664.[106] Lisa Jardine[107] doubts that Holmes reported the results of the trial accurately, and Samuel Pepys expressed his doubts at the time: The said master [i.e. the captain of Holmes' ship] affirmed, that the vulgar reckoning proved as near as that of the watches, which [the clocks], added he, had varied from one another unequally, sometimes backward, sometimes forward, to 4, 6, 7, 3, 5 minutes; as also that they had been corrected by the usual account.

A trial for the French Academy on an expedition to Cayenne ended badly. Jean Richer suggested correction for the figure of the Earth. By the time of the Dutch East India Company expedition of 1686 to the Cape of Good Hope, Huygens was able to supply the correction retrospectively.[108]

Pendulums[]

In 1673 Huygens published the Horologium Oscillatorium sive de motu pendulorum, his major work on pendulums and horology. The motivation came from the observation, made by Mersenne and others, that pendulums are not quite isochronous: their period depends on their width of swing, with wide swings taking slightly longer than narrow swings.[109][110]

Huygens analyzed this problem by finding the curve down which a mass will slide under the influence of gravity in the same amount of time, regardless of its starting point; the so-called tautochrone problem. By geometrical methods which anticipated the calculus, he showed it to be a cycloid, rather than the circular arc of a pendulum's bob, and therefore that pendulums needed to move on a cycloid path in order to be isochronous. The mathematics necessary to solve this problem led Huygens to develop his theory of evolutes, which he presented in Part III of his Horologium Oscillatorium.[7][37]

He also solved a problem posed by Mersenne earlier: how to calculate the period of a pendulum made of an arbitrarily-shaped swinging rigid body. This involved discovering the center of oscillation and its reciprocal relationship with the pivot point. In the same work, he analyzed the conical pendulum, consisting of a weight on a cord moving in a circle, using the concept of centrifugal force.

Huygens was the first to derive the formula for the period of an ideal mathematical pendulum (with massless rod or cord and length much longer than its swing), in modern notation:

with T the period, l the length of the pendulum and g the gravitational acceleration. By his study of the oscillation period of compound pendulums Huygens made pivotal contributions to the development of the concept of moment of inertia.[92]

Huygens also observed coupled oscillations: two of his pendulum clocks mounted next to each other on the same support often became synchronized, swinging in opposite directions. He reported the results by letter to the Royal Society, and it is referred to as "an odd kind of sympathy" in the Society's minutes.[111][112] This concept is now known as entrainment.

Balance spring watch[]

Huygens developed a balance spring watch at the same time as, though independently of, Robert Hooke. Controversy over the priority persisted for centuries. In February 2006, a long-lost copy of Hooke's handwritten notes from several decades of Royal Society meetings was discovered in a cupboard in Hampshire, England, presumably tipping the evidence in Hooke's favor.[113][114]

Huygens's design employed a spiral balance spring, but he used this form of spring initially only because the balance in his first watch rotated more than one and a half turns. He later used spiral springs in more conventional watches, made for him by Thuret in Paris from around 1675. Such springs are essential in modern watches with a detached lever escapement because they can be adjusted for isochronism. Watches in Huygens's time, however, employed the very undetached verge escapement. It interfered with the isochronal properties of any form of balance spring, spiral or otherwise.

In 1675, Huygens patented a pocket watch. The watches which were made in Paris from c. 1675 following Huygens's design are notable for lacking a fusee for equalizing the mainspring torque. The implication is that Huygens thought that his spiral spring would isochronise the balance, in the same way that he thought that the cycloidally shaped suspension curbs on his clocks would isochronise the pendulum.

Optics[]

In optics Huygens is remembered especially for his wave theory of light, which he first communicated in 1678 to the Académie des sciences in Paris. His theory was published in 1690 under the title Traité de la Lumière[115] (Treatise on light[116]), making it the first mathematical theory of light. He refers to Ignace-Gaston Pardies, whose manuscript on optics helped him on his wave theory.[117]

Huygens assumes that the speed of light is finite, as had been shown in an experiment by Ole Christensen Rømer in 1679, but which Huygens is presumed to have already believed.[118] The challenge at the time was to explain geometrical optics, as most physical optics phenomena (such as diffraction) had not been observed or appreciated as issues. Huygens's theory posits light as radiating wavefronts, with the common notion of light rays depicting propagation normal to those wavefronts. Propagation of the wavefronts is then explained as the result of spherical waves being emitted at every point along the wave front (the Huygens–Fresnel principle).[119] It assumed an omnipresent ether, with transmission through perfectly elastic particles, a revision of the view of Descartes. The nature of light was therefore a longitudinal wave.[118]

Huygens had experimented in 1672 with double refraction (birefringence) in the Iceland spar (a calcite), a phenomenon discovered in 1669 by Rasmus Bartholin. At first he could not elucidate what he found.[49] He later explained it[116] with his wave front theory and concept of evolutes. He also developed ideas on caustics.[120] Newton in his Opticks of 1704 proposed instead a corpuscular theory of light. The theory of Huygens was not widely accepted, one strong objection being that longitudinal waves have only a single polarization which cannot explain the observed birefringence. However the 1801 interference experiments of Thomas Young and François Arago's 1819 detection of the Poisson spot could not be explained through any particle theory, reviving the ideas of Huygens and wave models. In 1821 Fresnel was able to explain birefringence as a result of light being not a longitudinal (as had been assumed) but actually a transverse wave.[121] The thus-named Huygens–Fresnel principle was the basis for the advancement of physical optics, explaining all aspects of light propagation. It was only understanding the detailed interaction of light with atoms that awaited quantum mechanics and the discovery of the photon.

Huygens investigated the use of lenses in projectors. He is credited as the inventor of the magic lantern, described in correspondence of 1659.[122] There are others to whom such a lantern device has been attributed, such as Giambattista della Porta and Cornelis Drebbel, though Huygens's design used lens for better projection (Athanasius Kircher has also been credited for that).[123]

Astronomy[]

Saturn's rings and Titan[]

In 1655, Huygens was the first to propose that the rings of Saturn were "a thin, flat ring, nowhere touching, and inclined to the ecliptic”.[124] Using a refracting telescope with a 43x magnification that he designed himself,[12][13] Huygens also discovered the first of Saturn's moons, Titan.[125] In the same year he observed and sketched the Orion Nebula. His drawing, the first such known of the Orion nebula, was published in Systema Saturnium in 1659. Using his modern telescope he succeeded in subdividing the nebula into different stars. The brighter interior now bears the name of the Huygenian region in his honor.[126] He also discovered several interstellar nebulae and some double stars.

Mars and Syrtis Major[]

In 1659, Huygens was the first to observe a surface feature on another planet, Syrtis Major, a volcanic plain on Mars. He used repeated observations of the movement of this feature over the course of a number of days to estimate the length of day on Mars, which he did quite accurately to 24 1/2 hours. This figure is only a few minutes off of the actual length of the Martian day of 24 hours, 37 minutes.[127]

Planetarium[]

At the instigation of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Huygens undertook the task of constructing a mechanical planetarium that could display all the planets and their moons then known circling around the Sun. Huygens completed his design in 1680 and had his clockmaker Johannes van Ceulen built it the following year. However, Colbert passed away in the interim and Huygens never got to deliver his planetarium to the French Academy of Sciences as the new minister, Fracois-Michel le Tellier, decided not to renew Huygens's contract.[128][129]

In his design, Huygens made an ingenious use of continued fractions to find the best rational approximations by which he could choose the gears with the correct number of teeth. The ratio between two gears determined the orbital periods of two planets. To move the planets around the Sun, Huygens used a clock-mechanism that could go forwards and backwards in time. Huygens claimed his planetarium was more accurate that a similar device constructed by Ole Rømer around the same time, but his planetarium design was not published until after his death in the Opuscula posthuma (1703).[128]

Cosmotheoros[]

Shortly before his death in 1695, Huygens completed Cosmotheoros. At his direction, it was to be published only posthumously by his brother, which Constantijn Jr. did in 1698.[130] In it he speculated on the existence of extraterrestrial life, on other planets, which he imagined was similar to that on Earth. Such speculations were not uncommon at the time, justified by Copernicanism or the plenitude principle. But Huygens went into greater detail,[131] although without the benefit of understanding Newton's laws of gravitation, or the fact that the atmospheres on other planets are composed of different gases.[132] The work, translated into English in its year of publication and entitled The Celestial Worlds Discover’d, has been seen as being in the fanciful tradition of Francis Godwin, John Wilkins, and Cyrano de Bergerac, and fundamentally Utopian; and also to owe in its concept of planet to cosmography in the sense of Peter Heylin.[133][134]

Huygens wrote that availability of water in liquid form was essential for life and that the properties of water must vary from planet to planet to suit the temperature range. He took his observations of dark and bright spots on the surfaces of Mars and Jupiter to be evidence of water and ice on those planets.[135] He argued that extraterrestrial life is neither confirmed nor denied by the Bible, and questioned why God would create the other planets if they were not to serve a greater purpose than that of being admired from Earth. Huygens postulated that the great distance between the planets signified that God had not intended for beings on one to know about the beings on the others, and had not foreseen how much humans would advance in scientific knowledge.[136]

It was also in this book that Huygens published his method for estimating stellar distances. He made a series of smaller holes in a screen facing the Sun, until he estimated the light was of the same intensity as that of the star Sirius. He then calculated that the angle of this hole was th the diameter of the Sun, and thus it was about 30,000 times as far away, on the (incorrect) assumption that Sirius is as luminous as the Sun. The subject of photometry remained in its infancy until the time of Pierre Bouguer and Johann Heinrich Lambert.[137]

Legacy[]

During his lifetime, Huygens's influence was immense but began to fade shortly after his death. Nonetheless, he was held in high esteem by many, including Leibniz, Newton, l'Hospital, and the Bernoullis.

Mathematics and physics[]

In mathematics, Huygens mastered the methods of ancient Greek geometry, particularly the work of Archimedes, and was an adept user of the analytic geometry of Descartes and the infinitesimal techniques of Fermat and others.[138] His mathematical style can be characterized as geometrical infinitesimal analysis of curves and of motion. It drew inspiration and imagery from mechanics, while remaining pure mathematics in form.[139] Huygens brought this type of geometrical analysis to its greatest height but also to its conclusion, as more mathematicians turned away from classical geometry to the calculus for handling infinitesimals, limit processes, and motion.[39]

Huygens was moreover one of the first to fully employ mathematics to answer questions of physics. Often this entailed introducing a simple model for describing a complicated situation, then analyzing it starting from simple arguments to their logical consequences, developing the necessary mathematics along the way. As he wrote at the end of a draft of De Vi Centrifuga:[37]

Whatever you will have supposed not impossible either concerning gravity or motion or any other matter, if then you prove something concerning the magnitude of a line, surface, or body, it will be true; as for instance, Archimedes on the quadrature of the parabola, where the tendency of heavy objects has been assumed to act through parallel lines.

Huygens favored axiomatic presentations of his results, which demanded rigorous methods of geometric demonstration; although he allowed levels of probability regarding the primary axioms and hypotheses used, there could be no doubt in the proof of theorems derived from these. Thus, his published works were always precise, crystal clear, and elegant, and exerted a big influence in Newton's presentation of his own major work.[140]

Besides the application of mathematics to physics and physics to mathematics, Huygens relied on mathematics as methodology, particularly its predictive power to generate new knowledge about the world.[141] In this respect, he differed from Galileo in that he used mathematics as a method of discovery and analysis, not merely as rhetoric or synthesis, and the cumulative effect of Huygens's highly successful approach created a norm for eighteenth-century scientist such as Johann Bernoulli.[79]

Later influence[]

Unfortunately, Huygens's very idiosyncratic style and his reluctance in publishing his work greatly diminished his influence in the aftermath of the scientific revolution, as adherents of Leibniz’ calculus and Newton's physics took center stage.[39][138]

Still, his analysis of curves that satisfy certain physical properties, such as the cycloid, led to later studies of many other such curves like the caustic, the brachistochrone, the sail curve, and the catenary.[37] His application of mathematics to physics, such as in his analysis of double refraction, would inspire the development of mathematical physics and rational mechanics in the following century (albeit in the language of the calculus).[9] Finally, his pendulum clocks were the first reliable timekeepers fit for scientific use, and provided an example for others of work in applied mathematics in the years following his death.[7]

Portraits[]

During his lifetime[]

- 1639 – His father Constantijn Huygens in the midst of his five children by Adriaen Hanneman, painting with medallions, Mauritshuis, The Hague[142]

- 1671 – Portrait by Caspar Netscher, Museum Boerhaave, Leiden, loan from [142]

- ~1675 – Possible depiction of Huygens on l'French: Établissement de l'Académie des Sciences et fondation de l'observatoire, 1666 by Henri Testelin. Colbert presents the members of the newly founded Académie des Sciences to king Louis XIV of France. Musée National du Château et des Trianons de Versailles, Versailles[143][144]

- 1679 – Medaillon portrait in relief by the French sculptor Jean-Jacques Clérion[142]

- 1686 – Portrait in pastel by Bernard Vaillant, Museum Hofwijck, Voorburg[142]

- between 1684 and 1687 – Engraving by G. Edelinck after the painting by Caspar Netscher[142]

- 1688 – Portrait by Pierre Bourguignon (painter), Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Amsterdam[142]

Statues[]

Rotterdam

Delft

Leiden

Haarlem

Voorburg

Named after Huygens[]

Science[]

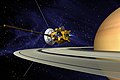

- The Huygens probe: The lander for the Saturnian moon Titan, part of the Cassini–Huygens mission to Saturn

- Asteroid 2801 Huygens

- A crater on Mars

- Mons Huygens, a mountain on the Moon

- Huygens Software, a microscope image processing package.

- A two element eyepiece designed by him. An early step in the development of the achromatic lens, since it corrects some chromatic aberration.

- The Huygens–Fresnel principle, a simple model to understand disturbances in wave propagation.

- Huygens wavelets, the fundamental mathematical basis for scalar diffraction theory

Other[]

- Medisch- Natuurphilosophisch en Veterinair- Tandheelkundig Gezelschap "Christiaan Huygens", scientific discussion group

- Huygens Lyceum, High School located in Eindhoven, Netherlands.

- The Christiaan Huygens, a ship of the Nederland Line.

- Huygens Scholarship Programme for international students and Dutch students

- W.I.S.V. Christiaan Huygens: Dutch study guild for the studies Mathematics and Computer Science at the Delft University of Technology

- Huygens Laboratory: Home of the Physics department at Leiden University, Netherlands

- Huygens Supercomputer: National Supercomputer facility of the Netherlands, located at in Amsterdam

- The Huygens-building in Noordwijk, Netherlands, first building on the Space Business park opposite Estec (ESA)

- The Huygens-building at the Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands. One of the major buildings of the science department at the university of Nijmegen.

- Christiaan Huygensplein, a square in Amsterdam

Works[]

- 1650 – De iis quae liquido supernatant (About the parts above the water, unpublished)[145]

- 1651 – Theoremata de quadratura hyperboles, ellipsis et circuli, in Oeuvres Complètes, Tome XI, link from Internet Archive.

- 1654 – De circuli magnitudine inventa

- 1656 – Epistola, qua diluuntur ea quibus 'Εξέτασις [Exetasis] Cyclometriae Gregori à Sto. Vincentio impugnata fuit[146]

- 1656 – De Saturni Luna observatio nova (About the new observation of the moon of Saturn – discovery of Titan)[147]

- 1656 – De motu corporum ex percussione, published only in 1703[148]

- 1657 – De ratiociniis in ludo aleae = Van reeckening in spelen van geluck (translated by Frans van Schooten)

- 1659 – Systema saturnium (on the planet Saturn)

- 1659 – De vi centrifuga (Concerning the centrifugal force), published in 1703

- 1673 – Horologium oscillatorium sive de motu pendularium (theory and design of the pendulum clock, dedicated to Louis XIV of France) – View at the HathiTrust Digital Library

- 1684 – Astroscopia Compendiaria tubi optici molimine liberata (compound telescopes without a tube)

- 1685 – Memoriën aengaende het slijpen van glasen tot verrekijckers (How to grind telescope lenses)

- 1686 – Old Dutch: Kort onderwijs aengaende het gebruijck der horologiën tot het vinden der lenghten van Oost en West (How to use clocks to establish the longitude)[149]

- 1690 – Traité de la lumière (translated by Silvanus P. Thompson)

- 1690 – Discours de la cause de la pesanteur (Discourse about gravity, from 1669?)

- 1691 – Lettre touchant le cycle harmonique (Rotterdam, concerning the 31-tone system)

- 1698 – Cosmotheoros (solar system, cosmology, life in the universe)

- 1703 – Opuscula posthuma including

- De motu corporum ex percussione (Concerning the motions of colliding bodies – contains the first correct laws for collision, dating from 1656).

- Descriptio automati planetarii (description and design of a planetarium)

- 1724 – Novus cyclus harmonicus (Leiden, after Huygens's death)

- 1728 – Christiani Hugenii Zuilichemii, dum viveret Zelhemii toparchae, opuscula posthuma ... (pub. 1728) Alternate title: Opera reliqua, concerning optics and physics[150]

- 1888–1950 – Huygens, Christiaan. Oeuvres complètes. The Hague Complete work, editors D. Bierens de Haan (tome=deel 1–5), (6–10), D.J. Korteweg (11–15), A.A. Nijland (15), (16–22).

- Tome I: Correspondance 1638–1656 (1888).

- Tome II: Correspondance 1657–1659 (1889).

- Tome III: Correspondance 1660–1661 (1890).

- Tome IV: Correspondance 1662–1663 (1891).

- Tome V: Correspondance 1664–1665 (1893).

- Tome VI: Correspondance 1666–1669 (1895).

- Tome VII: Correspondance 1670–1675 (1897).

- Tome VIII: Correspondance 1676–1684 (1899).

- Tome IX: Correspondance 1685–1690 (1901).

- Tome X: Correspondance 1691–1695 (1905).

- Tome XI: Travaux mathématiques 1645–1651 (1908).

- Tome XII: Travaux mathématiques pures 1652–1656 (1910).

- Tome XIII, Fasc. I: Dioptrique 1653, 1666 (1916).

- Tome XIII, Fasc. II: Dioptrique 1685–1692 (1916).

- Tome XIV: Calcul des probabilités. Travaux de mathématiques pures 1655–1666 (1920).

- Tome XV: Observations astronomiques. Système de Saturne. Travaux astronomiques 1658–1666 (1925).

- Tome XVI: Mécanique jusqu’à 1666. Percussion. Question de l'existence et de la perceptibilité du mouvement absolu. Force centrifuge (1929).

- Tome XVII: L’horloge à pendule de 1651 à 1666. Travaux divers de physique, de mécanique et de technique de 1650 à 1666. Traité des couronnes et des parhélies (1662 ou 1663) (1932).

- Tome XVIII: L'horloge à pendule ou à balancier de 1666 à 1695. Anecdota (1934).

- Tome XIX: Mécanique théorique et physique de 1666 à 1695. Huygens à l'Académie royale des sciences (1937).

- Tome XX: Musique et mathématique. Musique. Mathématiques de 1666 à 1695 (1940).

- Tome XXI: Cosmologie (1944).

- Tome XXII: Supplément à la correspondance. Varia. Biographie de Chr. Huygens. Catalogue de la vente des livres de Chr. Huygens (1950).

See also[]

- History of the internal combustion engine

- List of largest optical telescopes historically

- Fokker Organ

- Seconds pendulum

Notes[]

- ^ The meaning of this painting is explained in Wybe Kuitert "Japanese Robes, Sharawadgi, and the landscape discourse of Sir William Temple and Constantijn Huygens" Garden History, 41, 2: (2013) pp.157-176, Plates II-VI and Garden History, 42, 1: (2014) p.130 ISSN 0307-1243 Online as PDF

- ^ I. Bernard Cohen; George E. Smith (25 April 2002). The Cambridge Companion to Newton. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-521-65696-2. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Niccolò Guicciardini (2009). Isaac Newton on mathematical certainty and method. MIT Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-262-01317-8. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Huygens, Christiaan". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Huygens". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Huygens". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Yoder, J. G. (2005), Grattan-Guinness, I.; Cooke, Roger; Corry, Leo; Crépel, Pierre (eds.), "Christiaan Huygens, book on the pendulum clock (1673)", Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640-1940, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, pp. 33–45, ISBN 978-0-444-50871-3

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dijksterhuis, F. J. (2005). Lenses and Waves: Christiaan Huygens and the Mathematical Science of Optics in the Seventeenth Century. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dijksterhuis, F.J. (2008) Stevin, Huygens and the Dutch republic. Nieuw archief voor wiskunde, 5, pp. 100-107.https://research.utwente.nl/files/6673130/Dijksterhuis_naw5-2008-09-2-100.pdf

- ^ Andriesse, C.D. (2005) Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge: 6

- ^ Andriesse, C.D. (2005) Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge: 354

- ^ Jump up to: a b Louwman, Peter (2004). "Christiaan Huygens and his telescopes". Titan - from Discovery to Encounter. 1278: 103–114. Bibcode:2004ESASP1278..103L.

- ^ Jump up to: a b van Helden, Albert (2004). "Huygens, Titan, and Saturn's ring". Titan - from Discovery to Encounter. 1278: 11–29. Bibcode:2004ESASP1278...11V.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shafer, G. (2018). Pascal's and Huygens's game-theoretic foundations for probability. [1]

- ^ Schneider, Ivo (1 January 2005). "Jakob Bernoulli, Ars conjectandi (1713)". Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640-1940: 88–104. doi:10.1016/B978-044450871-3/50087-5. ISBN 9780444508713.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schneider, Ivo (2001), Heyde, C. C.; Seneta, E.; Crépel, P.; Fienberg, S. E. (eds.), "Christiaan Huygens", Statisticians of the Centuries, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 23–28, doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0179-0_5, ISBN 978-1-4613-0179-0, retrieved 15 April 2021

- ^ Stephen J. Edberg (14 December 2012) Christiaan Huygens, Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695)". www.saburchill.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Henk J. M. Bos (14 December 2012) Huygens, Christiaan (Also Huyghens, Christian), Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008. Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ R. Dugas and P. Costabel, "Chapter Two, The Birth of a new Science" in The Beginnings of Modern Science, edited by Rene Taton, 1958,1964, Basic Books, Inc.

- ^ Strategic Affection? Gift Exchange in Seventeenth-Century Holland, by Irma Thoen, pg 127

- ^ Jump up to: a b Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem (1596–1687), by Adelheid Rech

- ^ The Heirs of Archimedes: Science and the Art of War Through the Age of Enlightenment, by Brett D. Steele, pg. 20

- ^ entoen.nu: Christiaan Huygens 1629–1695 Science in the Golden Age

- ^ Jozef T. Devreese (31 October 2008). 'Magic Is No Magic': The Wonderful World of Simon Stevin. WIT Press. pp. 275–6. ISBN 978-1-84564-391-1. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Yoeder, J. G. (1988). Unrolling Time. Cambridge University Press. pp. 169–179.

- ^ H. N. Jahnke (2003). A history of analysis. American Mathematical Soc. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8218-9050-9. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Margret Schuchard (2007). Bernhard Varenius: (1622–1650). BRILL. p. 112. ISBN 978-90-04-16363-8. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Dictionary, p. 470.

- ^ Christiaan Huygens – A family affair, by Bram Stoffele, pg 80.

- ^ C. D. Andriesse (25 August 2005). Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-0-521-85090-2. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ C. D. Andriesse (25 August 2005). Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–6. ISBN 978-0-521-85090-2. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dictionary, p. 469.

- ^ Lynn Thorndike (1 March 2003). History of Magic & Experimental Science 1923. Kessinger Publishing. p. 622. ISBN 978-0-7661-4316-6. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Leonhard Euler (1 January 1980). Clifford Truesdell (ed.). The Rational Mechanics of Flexible or Elastic Bodies 1638–1788: Introduction to Vol. X and XI. Springer. pp. 44–6. ISBN 978-3-7643-1441-5. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ C. D. Andriesse (25 August 2005). Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–9. ISBN 978-0-521-85090-2. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Yoder, J. G. (1989). Unrolling Time: Christiaan Huygens and the Mathematization of Nature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52481-0.

- ^ H.F. Cohen (31 May 1984). Quantifying Music: The Science of Music at the First Stage of Scientific Revolution 1580–1650. Springer. pp. 217–9. ISBN 978-90-277-1637-8. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c H. J. M. Bos (1993). Lectures in the History of Mathematics. American Mathematical Soc. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-8218-9675-4. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ C. D. Andriesse (25 August 2005). Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-521-85090-2. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Thomas Hobbes (1997). The Correspondence: 1660–1679. Oxford University Press. p. 868. ISBN 978-0-19-823748-8. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Michael S. Mahoney (1994). The Mathematical Career of Pierre de Fermat: 1601–1665. Princeton University Press. pp. 67–8. ISBN 978-0-691-03666-3. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ C. D. Andriesse (25 August 2005). Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-521-85090-2. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Christiaan Huygens | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Schoneveld, Cornelis W (1983). Intertraffic of the Mind: Studies in Seventeenth-century Anglo-Dutch Translation with a Checklist of Books Translated from English Into Dutch, 1600–1700. Brill Archive. p. 41. ISBN 978-90-04-06942-8. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Dictionary, p. 472.

- ^ Robert D. Huerta (2005). Vermeer And Plato: Painting The Ideal. Bucknell University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8387-5606-5. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Randy O. Wayne (28 July 2010). Light and Video Microscopy. Academic Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-08-092128-0. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dictionary, p. 473.

- ^ Margaret Gullan-Whur (1998). Within Reason: A Life of Spinoza. Jonathan Cape. pp. 170–1. ISBN 0-224-05046-X.

- ^ Ivor Grattan-Guinness (11 February 2005). Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640–1940. Elsevier. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ p963-965, Jan Gullberg, Mathematics from the birth of numbers, W. W. Norton & Company; ISBN 978-0-393-04002-9

- ^ Thomas Hobbes (1997). The Correspondence: 1660–1679. Oxford University Press. p. 841. ISBN 978-0-19-823748-8. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Garber and Ayers, p. 1124–5.

- ^ Anders Hald (25 February 2005). A History of Probability and Statistics and Their Applications before 1750. John Wiley & Sons. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-471-72517-6. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Peter Louwman, Christiaan Huygens and his telescopes, Proceedings of the International Conference, 13 – 17 April 2004, ESTEC, Noordwijk, Netherlands, ESA, sp 1278, Paris 2004

- ^ Adrian Johns (15 May 2009). The Nature of the Book: Print and Knowledge in the Making. University of Chicago Press. pp. 437–8. ISBN 978-0-226-40123-2. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Venus Seen on the Sun: The First Observation of a Transit of Venus by Jeremiah Horrocks. BRILL. 2 March 2012. p. xix. ISBN 978-90-04-22193-2. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Jozef T. Devreese (2008). 'Magic Is No Magic': The Wonderful World of Simon Stevin. WIT Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-84564-391-1. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Fokko Jan Dijksterhuis (1 October 2005). Lenses And Waves: Christiaan Huygens and the Mathematical Science of Optics in the Seventeenth Century. Springer. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-4020-2698-0. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Gerrit A. Lindeboom (1974). Boerhaave and Great Britain: Three Lectures on Boerhaave with Particular Reference to His Relations with Great Britain. Brill Archive. p. 15. ISBN 978-90-04-03843-1. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ David J. Sturdy (1995). Science and Social Status: The Members of the "Académie Des Sciences", 1666–1750. Boydell & Brewer. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-85115-395-7. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ The anatomy of a scientific institution: the Paris Academy of Sciences, 1666–1803. University of California Press. 1971. p. 7 note 12. ISBN 978-0-520-01818-1. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ David J. Sturdy (1995). Science and Social Status: The Members of the "Académie Des Sciences", 1666–1750. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 71–2. ISBN 978-0-85115-395-7. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ Jacob Soll (2009). The information master: Jean-Baptiste Colbert's secret state intelligence system. University of Michigan Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-472-11690-4. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ A. E. Bell, Christian Huygens (1950), pp. 65–6; archive.org.

- ^ Jonathan I. Israel (12 October 2006). Enlightenment Contested : Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670–1752: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670–1752. OUP Oxford. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-19-927922-7. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Lisa Jardine (2003). The Curious Life of Robert Hooke. HarperCollins. pp. 180–3. ISBN 0-00-714944-1.

- ^ Joseph Needham (1974). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology : the gunpowder epic. Cambridge University Press. p. 556. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Joseph Needham (1986). Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. p. xxxi. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Alfred Rupert Hall (1952). Ballistics in the Seventeenth Century: A Study in the Relations of Science and War with Reference Principally to England. CUP Archive. p. 63. GGKEY:UT7XX45BRJX. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Gottfried Wilhelm Freiherr von Leibniz (7 November 1996). Leibniz: New Essays on Human Understanding. Cambridge University Press. p. lxxxiii. ISBN 978-0-521-57660-4. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Marcelo Dascal (2010). The practice of reason. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 978-90-272-1887-2. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Alfred Rupert Hall (1886). Isaac Newton: Adventurer in thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-521-56669-X.

- ^ Curtis ROADS (1996). The computer music tutorial. MIT Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-262-68082-0. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ "GroteKerkDenHaag.nl" (in Dutch). GroteKerkDenHaag.nl. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ "never married; from google (christiaan huygens never married) result 1".

- ^ Anders Hald (25 February 2005). A History of Probability and Statistics and Their Applications before 1750. John Wiley & Sons. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-471-72517-6. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yoder, J. "'Following in the footsteps of geometry': The mathematical world of Christiaan Huygens". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ William L. Harper (8 December 2011). Isaac Newton's Scientific Method: Turning Data into Evidence about Gravity and Cosmology. Oxford University Press. pp. 206–7. ISBN 978-0-19-957040-9. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ R. C. Olby; G. N. Cantor; J. R. R. Christie; M. J. S. Hodge (1 June 2002). Companion to the History of Modern Science. Taylor & Francis. pp. 238–40. ISBN 978-0-415-14578-7. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ David B. Wilson (1 January 2009). Seeking nature's logic. Penn State Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-271-04616-7. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Stephen Shapin; Simon Schaffer (1989). Leviathan and the Air Pump. Princeton University Press. pp. 235–56. ISBN 0-691-02432-4.

- ^ Deborah Redman (1997). The Rise of Political Economy As a Science: Methodology and the Classical Economists. MIT Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-262-26425-9. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Tian Yu Cao (14 May 1998). Conceptual Developments of 20th Century Field Theories. Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-0-521-63420-5. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Garber and Ayers, p. 595.

- ^ Peter Dear (15 September 2008). The Intelligibility of Nature: How Science Makes Sense of the World. University of Chicago Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-226-13950-0. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ The Beginnings of Modern Science, edited by Rene Taton, Basic Books, 1958, 1964.

- ^ Garber and Ayers, pp. 666–7.

- ^ Garber and Ayers, p. 689.

- ^ Jonathan I. Israel (8 February 2001). Radical Enlightenment:Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650–1750. Oxford University Press. pp. lxii–lxiii. ISBN 978-0-19-162287-8. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ernst Mach, The Science of Mechanics (1919), e.g. pp. 143, 172, 187 <https://archive.org/details/scienceofmechani005860mbp>.

- ^ J. B. Barbour (1989). Absolute Or Relative Motion?: The discovery of dynamics. CUP Archive. p. 542. ISBN 978-0-521-32467-0. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ A.I. Sabra (1981). Theories of light: from Descartes to Newton. CUP Archive. pp. 166–9. ISBN 978-0-521-28436-3. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Richard Allen (1999). David Hartley on human nature. SUNY Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7914-9451-6. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Nicholas Jolley (1995). The Cambridge Companion to Leibniz. Cambridge University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-521-36769-1. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ "Boerhaave Museum Top Collection: Hague clock (Pendulum clock) (Room 3/Showcase V20)". Museumboerhaave.nl. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ "Boerhaave Museum Top Collection: Horologium oscillatorium, siue, de motu pendulorum ad horologia aptato demonstrationes geometricae (Room 3/Showcase V20)". Museumboerhaave.nl. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Marrison, Warren (1948). "The Evolution of the Quartz Crystal Clock". Bell System Technical Journal. 27 (3): 510–588. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01343.x. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007.

- ^ Epstein/Prak (2010). Guilds, Innovation and the European Economy, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. pp. 269–70. ISBN 978-1-139-47107-7. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Hans van den Ende: "Huygens's Legacy, The Golden Age of the Pendulum Clock", Fromanteel Ldt., 2004,

- ^ van Kersen, Frits & van den Ende, Hans: Oppwindende Klokken – De Gouden Eeuw van het Slingeruurwerk 12 September – 29 November 2004 [Exhibition Catalog Paleis Het Loo]; Apeldoorn: Paleis Het Loo,2004,

- ^ Hooijmaijers, Hans; Telling time – Devices for time measurement in museum Boerhaave – A Descriptive Catalogue; Leiden: Museum Boerhaave, 2005

- ^ No Author given; Chistiaan Huygens 1629–1695, Chapter 1: Slingeruurwerken; Leiden: Museum Boerhaave, 1988

- ^ Joella G. Yoder (8 July 2004). Unrolling Time: Christiaan Huygens and the Mathematization of Nature. Cambridge University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-521-52481-0. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Michael R. Matthews (2000). Time for Science Education: How Teaching the History and Philosophy of Pendulum Motion Can Contribute to Science Literacy. Springer. pp. 137–8. ISBN 978-0-306-45880-4. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Lisa Jardine (1 April 2008). "Chapter 10". Going Dutch: How the English Plundered Holland's Glory. HarperPress. ISBN 978-0007197323.

- ^ Dictionary, p. 471.

- ^ Marin Mersenne 1647 Reflectiones Physico-Mathematicae, Paris, Chapter 19, cited in Mahoney, Michael S. (1980). "Christian Huygens: The Measurement of Time and of Longitude at Sea". Studies on Christiaan Huygens. Swets. pp. 234–270. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Matthews, Michael R. (2000). Time for science education: how teaching the history and philosophy of pendulum motion can contribute to science literacy. New York: Springer. pp. 124–126. ISBN 0-306-45880-2.

- ^ Thomas Birch, "The History of the Royal Society of London, for Improving of Natural Knowledge, in which the most considerable of those papers...as a supplement to the Philosophical Transactions", vol 2, (1756) p 19.

- ^ A copy of the letter appears in C. Huygens, in Oeuvres Completes de Christian Huygens, edited by M. Nijhoff (Societe Hollandaise des Sciences, The Hague, The Netherlands, 1893), Vol. 5, p. 246 (in French).

- ^ Nature – International Weekly Journal of Science, number 439, pages 638–639, 9 February 2006

- ^ Notes and Records of the Royal Society (2006) 60, pages 235–239, 'Report – The Return of the Hooke Folio' by Robyn Adams and Lisa Jardine

- ^ Christiaan Huygens, Traité de la lumiere... (Leiden, Netherlands: Pieter van der Aa, 1690), Chapter 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b C. Huygens (1690), translated by Silvanus P. Thompson (1912), Treatise on Light, London: Macmillan, 1912; Project Gutenberg edition, 2005; Errata, 2016.

- ^ Traité de la lumiere... (Leiden, Netherlands: Pieter van der Aa, 1690), Chapter 1. From page 18

- ^ Jump up to: a b A. Mark Smith (1987). Descartes's Theory of Light and Refraction: A Discourse on Method. American Philosophical Society. p. 70 with note 10. ISBN 978-0-87169-773-8. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Shapiro, p. 208.

- ^ Ivor Grattan-Guinness (11 February 2005). Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640–1940. Elsevier. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Darryl J. Leiter; Sharon Leiter (1 January 2009). A to Z of Physicists. Infobase Publishing. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-4381-0922-0. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Jordan D. Marché (2005). Theaters Of Time And Space: American Planetariums, 1930–1970. Rutgers University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8135-3576-0. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ C. D. Andriesse (25 August 2005). Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-521-85090-2. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Baalke, R. (2011). "Historical Background of Saturn's Rings". solarviews.com. Later, it was determined that Saturn's rings were not solid but made of several smaller bodies.

- ^ Ron Baalke, Historical Background of Saturn's Rings Archived 21 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Antony Cooke (1 January 2005). Visual Astronomy Under Dark Skies: A New Approach to Observing Deep Space. Springer. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-84628-149-5. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "A dark spot on Mars - Syrtis Major". www.marsdaily.com. 3 February 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b van den Bosch, D. (2018). The application of continued fractions in Christiaan Huygens' planetarium.[2]

- ^ Amin, H. H. N. (2008). Christiaan Huygens' planetarium

- ^ Aldersey-Williams, Hugh, The Uncertain Heavens, Public Domain Review, October 21, 2020

- ^ Philip C. Almond (27 November 2008). Adam and Eve in Seventeenth-Century Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–2. ISBN 978-0-521-09084-1. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Engines of Our Ingenuity 1329: Life In Outer Space – In 1698". www.houstonpublicmedia.org. University of Houston.

- ^ Postmus, Bouwe (1987). "Plokhoy's A way pronouned: Mennonite Utopia or Millennium?". In Dominic Baker-Smith; Cedric Charles Barfoot (eds.). Between dream and nature: essays on utopia and dystopia. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 86–8. ISBN 978-90-6203-959-3. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Juliet Cummins; David Burchell (2007). Science, Literature, and Rhetoric in Early Modern England. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 194–5. ISBN 978-0-7546-5781-1. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Johar Huzefa (2009) Nothing But The Facts – Christiaan Huygens". Brighthub.com. 28 September 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ^ Jacob, Margaret (2010). The Scientific Revolution. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 29, 107–114.

- ^ Russell Mccormmach (2012). Weighing the World: The Reverend John Michell of Thornhill. Springer. pp. 129–31. ISBN 978-94-007-2022-0. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dijksterhuis, E. J. (1953). "Christiaan Huygens; an address delivered at the annual meeting of the Holland Society of Sciences at Haarlem, May 13th, 1950, on the occasion of the completion of Huygens's Collected Works". Centaurus; International Magazine of the History of Science and Medicine. 2 (4): 265–282. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1953.tb00409.x.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

complete dictionarywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Elzinga, A. (1972). On a research program in early modern physics. Akademiförlaget.

- ^ Gijsbers, V. (2003). "Christiaan Huygens and the scientific revolution". Proceedings of the International Conference "Titan - from discovery to encounter", 13-17 April 2004, ESTEC, Noordwijk, Netherlands. ESA Publications Division. pp. 171–178.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Verduin, C.J. Kees (31 March 2009). "Portraits of Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695)". University of Leiden. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Verduin, C.J. (2004). "A portrait of Christiaan Huygens together with Giovanni Domenico Cassini". In Karen, Fletcher (ed.). Titan – from discovery to encounter. 1278. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. pp. 157–170. Bibcode:2004ESASP1278..157V. ISBN 92-9092-997-9.

- ^ Verduin, C. J. K. (2008). A portrait of Christiaan Huygens?

- ^ L, H (1907). "Christiaan Huygens, Traité: De iis quae liquido supernatant". Nature. 76 (1972): 381. Bibcode:1907Natur..76..381L. doi:10.1038/076381a0. S2CID 4045325.

- ^ Yoder, Joella (17 May 2013). A Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Christiaan Huygens including a concordance with his Oeuvres Complètes. BRILL. ISBN 9789004235656. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Audouin, Dollfus (2004). "Christiaan Huygens as telescope maker and planetary observer". In Karen, Fletcher (ed.). Titan – from discovery to encounter. 1278. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. pp. 115–132. Bibcode:2004ESASP1278..115D. ISBN 92-9092-997-9.

- ^ Huygens, Christiaan (1977). Translated by Blackwell, Richard J. "Christiaan Huygens' The Motion of Colliding Bodies". Isis. 68 (4): 574–597. doi:10.1086/351876. JSTOR 230011. S2CID 144406041.

- ^ "Christiaan Huygens, Oeuvres complètes. Tome XXII. Supplément à la correspondance" (in Dutch). Digitale Bibliotheek Voor de Nederlandse Lettern. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Yoeder, Joella (1991). "Christiaan Huygens' Great Treasure" (PDF). Tractrix. 3: 1–13.

References[]

- Bell, A. E. (1947). Christian Huygens and the Development of Science in the Seventeenth Century. Edward Arnold & Co, London.

- Daniel Garber (2003). The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-century Philosophy (2 vols.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53720-9. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Alan E. Shapiro (1973) Kinematic Optics: A Study of the Wave Theory of Light in the Seventeenth Century, Archive for History of Exact Sciences 11(2/3): 134–266 via Jstor

- Wiep van Bunge et al. (editors), The Dictionary of Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Dutch Philosophers (2003), Thoemmes Press (two volumes), article Huygens, Christiaan, p. 468–77.

Further reading[]

- Andriesse, C.D., 2005, Huygens: The Man Behind the Principle. Foreword by Sally Miedema. Cambridge University Press.

- Boyer, C.B. (1968) A History of Mathematics, New York.

- Dijksterhuis, E. J. (1961) The Mechanization of the World Picture: Pythagoras to Newton

- Hooijmaijers, H. (2005) Telling time – Devices for time measurement in Museum Boerhaave – A Descriptive Catalogue, Leiden, Museum Boerhaave.

- Struik, D.J. (1948) A Concise History of Mathematics

- Van den Ende, H. et al. (2004) Huygens's Legacy, The golden age of the pendulum clock, Fromanteel Ltd, Castle Town, Isle of Man.

- Yoder, J G. (2005) "Book on the pendulum clock" in Ivor Grattan-Guinness, ed., Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics. Elsevier: 33–45.

- Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) : Library of Congress Citations. Retrieved 30 March 2005.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christiaan Huygens. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Christiaan Huygens |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Huygens, Christiaan . |

Primary sources, translations[]

- Works by Christiaan Huygens at Project Gutenberg:

- C. Huygens (translated by Silvanus P. Thompson, 1912), Treatise on Light; Errata.

- Works by or about Christiaan Huygens at Internet Archive

- Works by Christiaan Huygens at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Correspondence of Christiaan Huygens at Early Modern Letters Online

- De Ratiociniis in Ludo Aleae or The Value of all Chances in Games of Fortune, 1657 Christiaan Huygens's book on probability theory. An English translation published in 1714. Text pdf file.

- Horologium oscillatorium (German translation, pub. 1913) or Horologium oscillatorium (English translation by Ian Bruce) on the pendulum clock

- ΚΟΣΜΟΘΕΩΡΟΣ (Cosmotheoros). (English translation of Latin, pub. 1698; subtitled The celestial worlds discover'd: or, Conjectures concerning the inhabitants, plants and productions of the worlds in the planets.)

- C. Huygens (translated by Silvanus P. Thompson), Traité de la lumière or Treatise on light, London: Macmillan, 1912, archive.org/details/treatiseonlight031310mbp; New York: Dover, 1962; Project Gutenberg, 2005, gutenberg.org/ebooks/14725; Errata

- Systema Saturnium 1659 text a digital edition of Smithsonian Libraries

- On Centrifugal Force (1703)

- Huygens's work at WorldCat

- The Correspondence of Christiaan Huygens in EMLO

- Christiaan Huygens biography and achievements

- Portraits of Christiaan Huygens

- Huygens's books, in digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library:

- (1659) Systema Saturnium (Latin)

- (1684) Astroscopia compendiaria (Latin)

- (1690) Traité de la lumiére (French)

- (1698) ΚΟΣΜΟΘΕΩΡΟΣ, sive De terris cœlestibus (Latin)

Museums[]

- Huygensmuseum Hofwijck in Voorburg, Netherlands, where Huygens lived and worked.

- Huygens Clocks exhibition from the Science Museum, London

- Online exhibition on Huygens in Leiden University Library (in Dutch)

Other[]

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Christiaan Huygens", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- Huygens and music theory Huygens–Fokker Foundation —on Huygens's 31 equal temperament and how it has been used

- Christiaan Huygens on the 25 Dutch Guilder banknote of the 1950s.

- Christiaan Huygens at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- How to pronounce "Huygens"

- Christiaan Huygens

- 1629 births

- 1695 deaths

- Discoverers of moons

- Dutch music theorists

- 17th-century Dutch scientists

- Optical physicists

- Theoretical physicists

- Geometers

- Dutch clockmakers

- Dutch scientific instrument makers

- Original Fellows of the Royal Society

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Leiden University alumni

- Huygens family

- Dutch members of the Dutch Reformed Church

- Scientists from The Hague

- 17th-century Latin-language writers

- Age of Enlightenment

- Astronomy in the Dutch Republic

- 17th-century Dutch inventors

- 17th-century Dutch mathematicians

- 17th-century Dutch philosophers

- 17th-century Dutch writers