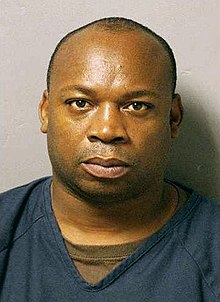

Christopher Coke

Christopher Coke | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Christopher Michael Coke 13 March 1969 |

| Other names | Dudus, Paul Christopher Scott, Presi, President, General, Shortman, Omar Clark[1] |

| Occupation | Head of the Shower Posse |

| Criminal status | Serving a 23-year sentence at the Federal Correctional Institution, Fort Dix |

Christopher Michael Coke, also known as Dudus[2] (born 13 March 1969),[3] is a convicted Jamaican drug lord and the leader of the Shower Posse, a violent drug gang started by his father Lester Coke in Jamaica, which exported "large quantities"[4] of marijuana and cocaine into the United States.

Due to their father's drug profits, Christopher and his siblings grew up amidst wealth and attended elite private schools. His sister and brother were killed in drug-related violence, in 1987 and 2004, respectively. Coke was gradually brought into his father's organization.

After his father's death in 1992, Coke, at the age of 23, became leader of the gang and the de facto leader of the Tivoli Gardens community in West Kingston. He developed community programs to help the poor and had so much local support that Jamaican police were unable to enter this neighborhood without community consent.[2]

Coke was arrested on drug charges and extradited to the United States in 2010. His arrest had provoked violence among Coke's supporters in West Kingston. In 2011, Coke pleaded guilty to federal racketeering charges in connection with drug trafficking and assault. On 8 June 2012, he was sentenced by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York to 23 years in federal prison.

Early life[]

Christopher Michael Coke was born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1969, the youngest son of Lester Lloyd Coke and Patricia Halliburton. He had an older sister and brother.

His father Lester Coke, who was also known as "Jim Brown", was the founder of a violent drug gang called the Shower Posse. Together with the gang's co-founder Vivian Blake, Lester Coke oversaw the distribution of huge amounts of cocaine and marijuana throughout Jamaica and the United States; they were blamed for more than 1000 murders in both countries during the late 1980s and early 1990s.[5]

The gang ruled the Tivoli Gardens neighborhood of West Kingston, where the Coke family lived. Although the area had a history of extreme poverty, Coke earned immense wealth from the gang's profits and his family lived in luxury. Christopher Coke and his siblings attended school with children of the country's political elite. The family suffered from the violence associated with the competition of the drug trade and their father's activities. Coke's sister was fatally shot in 1987. Coke's brother was killed in 2004.[6]

The United States Department of Justice indicted Lester Coke and other key members of the gang, including Vivian Blake, on drug trafficking and murder charges in 1990. Jamaican authorities arrested them. Two years after his arrest, the senior Coke died in a mysterious fire at the General Penitentiary in Kingston, where he was being held pending extradition proceedings.[6]

Rise to power[]

Christopher Coke had been incorporated into his father's trusted assistants. He effectively began to rule the gang at the age of 23, after his father died. He also developed himself as a community leader in Tivoli Gardens. He distributed money to the area's poor, created employment, and set up community centers to help the children and others.[7] He gained widespread support in the community, to the extent that Jamaican police had to seek permission from his organization before entering the neighborhood.[2]

Extradition request and violence[]

In 2009 the United States first asked the Jamaican government for the extradition of Coke on drug trafficking charges.[8][9]

Bruce Golding, the prime minister of Jamaica and leader of the Jamaica Labour Party, initially refused to extradite Coke. He claimed that the US had used warrantless wiretapping to gather evidence on Coke.[10] Eavesdropping evidence precipitated the US call for extradition.[2] On 17 May 2010, Golding relented and the government issued a warrant for Coke's arrest.[11]

The Senator Tom Tavares-Finson withdrew as Coke's attorney on 18 May 2010 "in order to avoid conflict of interest."[12]

Following this news, Coke's supporters began protesting and arming themselves. In late May 2010, the national government placed Kingston under a state of emergency after a series of shootings and firebombings within the city.[13] On 24 May 2010, military and police forces launched a large-scale operation in Kingston to arrest Coke.[14] By 27 May, at least 73 people had been killed in clashes between Jamaican security forces and gunmen in West Kingston, primarily in the neighbourhood of Tivoli Gardens.[15] This casualty toll has climbed to a confirmed number of 76 dead victims.[16] Mattathias Schwartz, writing for The New Yorker, reported the death toll at 74, including one soldier.[citation needed]

In 2013, the Government of Jamaica announced it would set up a Commission of Inquiry to investigate and report on the operation: the commission, informally known as the Tivoli Inquiry, first sat in December 2014. It is chaired by Barbados judge Sir David Simmons with Justice and Professor [17] and QC.[18]

Capture[]

Coke was detained during a routine roadblock while trying to reach the US Embassy in Kingston for surrender. He attempted to disguise himself as a woman, wearing a woman's wig and possessing a second one and a pair of women's sunglasses, however the security forces recognized him through his disguise.[19] Reverend Al Miller, an influential evangelical priest, was also detained while trying to facilitate the surrender. Miller told police Coke feared for his life if he surrendered directly to the police, and was asked for aid by Coke. Miller had previously facilitated the surrender of Coke's brother one month earlier.[20][21]

Fearing for his safety, Coke voluntarily waived his right to an extradition trial so that he could be taken to the US to be tried. Coke's father had died in 1992 in a mysterious prison fire while awaiting an extradition trial in Jamaica.[6] Coke was held under heavy guard while awaiting extradition, as the police feared an attack by his supporters.[22]

Coke said that his decision to surrender and face charges was based on a desire to end the drug-related violence in Jamaica,[23] to which he'd lost his sister, brother and father. He said:

"I take this decision for I now believe it to be in the best interest of my family, the community of western Kingston and in particular the people of Tivoli Gardens and above all Jamaica."[23]

US Federal court proceedings[]

Coke was held at the federal New York City Metropolitan Correctional Center during the court proceedings.[24] Coke initially pleaded not guilty to federal drug trafficking and weapons trafficking charges in May 2011.[23][25] On 30 August 2011, he pleaded guilty in front of Judge Robert P. Patterson, Jr. of United States District Court for the Southern District of New York to the following charges: racketeering conspiracy for trafficking large quantities of marijuana and cocaine into the United States, and conspiracy to commit assault in aid of racketeering, for his approval of the stabbing attack of a marijuana dealer in New York City.[4]

Initially scheduled for 8 December 2011, Judge Patterson postponed Coke's sentencing several times to provide time for Coke's defense attorneys and federal prosecutors to obtain information supporting their arguments as to the sentence.[26] Defense attorneys cited members of Coke's family and other supporters, who portrayed him as a benevolent, philanthropic, and well-mannered individual. By contrast, federal prosecutors presented documents depicting Coke as willing to commit brutal acts of violence to support his drug empire, and implicating him in at least five murders. In one, he allegedly dismembered the victim with a chainsaw[27] for stealing drugs from him. The Jamaican government provided evidence derived from wiretapping Coke's cellphone prior to his arrest; it had recorded at least 50,000 conversations dating back to 2004.[28][29][30][31] On 8 June 2012 Coke was sentenced to 23 years in prison.[32] He is now held at the Federal Correctional Institution, Fort Dix in Fort Dix, New Jersey with a release date of 25 January 2030.[33] He has a register number of 02257-748.[34]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Who is 'Dudus'?". The Jamaica Gleaner. 24 May 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Schwartz, Mattathias (12 December 2011), "A Massacre in Jamaica", The New Yorker, pp. 62–71, retrieved 26 December 2011

- ^ "Who is 'Dudus'?". jamaica-gleaner.com. 24 May 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goldstein, Joseph (31 August 2011). "Christopher Coke Pleads Guilty in New York". The New York Times.

- ^ "Profile: Christopher 'Dudus' Coke". BBC News. 31 August 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Cokes Then and Now". The Jamaica Observer. 6 September 2009. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ "Extraditing Coke", Al Jazeera, 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Tension in Tivoli as US awaits word on Dudus's extradition". The Jamaica Observer. 3 September 2009. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ "EDITORIAL - This is not Somalia, we hope". The Jamaica Gleaner. 6 September 2009. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009.

- ^ "Golding's Sternest Political Test". The Jamaica Observer. 15 March 2010. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ^ "Prime Minister Shifts on Approving an Extradition". The New York Times. Associated Press. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Tavares-Finson withdraws as arrest warrant out for 'Dudus'". The Daily Herald. 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Jamaica Declares State of Emergency". The New York Times. Reuters. 23 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Jamaica police storm stronghold of alleged drugs lord". BBC News. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Toll from crackdown on Jamaica slum climbs to 73" Reuters, 27 May 2010.

- ^ "Alleged Jamaican Drug Kingpin Pleads Not Guilty", CNN, 25 June 2010.

- ^ Henry, Paul (1 December 2014). "Tivoli enquiry opens today". Jamaica Observer.

- ^ "Commissioners appointed". Jamaica Gleaner.

- ^ Caroll, Rory (23 June 2010). "Jamaica appeals for calm after surrender of Christopher 'Dudus' Coke". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Jamaican kingpin's reign comes to a quiet end". 23 June 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Walker, Karyl (23 June 2010). "Al Miller turns himself in". Jamaica Observer. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Jamaica 'drug lord' arrives in US", Al Jazeera, Accessed 25 June 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "'Drug lord' pleads not guilty in US". 25 June 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Christopher Coke", Bureau of Prisons

- ^ "Alleged Jamaican drug lord Coke extradited to US" Archived 16 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Voice of America News, 24 June 2010

- ^ "Jamaican drug lord 'Dudus' obtains sentencing delay". Reuters. 16 March 2012.

- ^ "Page 105 power saw Transcript of Christopher Michael Coke". . 22–23 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ "Golding's sternest political test"], Jamaica Observer, 15 March 2010

- ^ 2 February 2007 "Jamaican Gov't seeks to have Coke's phone tapped" Archived 21 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Jamaica Observer, 2 February 2007

- ^ Lewin, "Cop who tapped Dudus' phone broke no law" Archived 21 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Jamaica Observer, 21 May 2010

- ^ "Christopher Coke Pleads Guilty in New York", New York Times, 31 August 2011

- ^ "Christopher 'Dudus' Coke handed 23-year US jail term for drug trafficking". The Guardian. 8 June 2012.

- ^ "No Locks, No Bars - 'Dudus' Moved To Low-Security Prison", Jamaica Gleaner, 11 May 2017

- ^ https://www.bop.gov/inmateloc/

External links[]

- "Indictment of Christopher Coke", American Law Daily blog

- "USA vs CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL COKE (1:07-cr-00971-RPP), May 22-23, 2012", Trial transcript

- Mary Vallis, "Police raids reveal links to powerful Jamaican Shower Posse gang", The National Post, 4 May 2010.

- Denise Balkissoon, "Deadly Shower Posse gang has deep ties to Toronto", The Toronto Star, 25 May 2010

- "Critics: Rising Jamaican Death Toll Rooted in So-Called 'War on Drugs'", Democracy Now! video report, 28 May 2010

- 1969 births

- Fugitives wanted by Jamaica

- Jamaican drug traffickers

- Jamaican crime bosses

- Jamaican people imprisoned abroad

- Living people

- People extradited from Jamaica

- People extradited to the United States

- People from Kingston, Jamaica

- Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government

- Shower Posse

- Yardies