Chronicle Publishing Company

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

The San Francisco Chronicle was the foundation of the Chronicle Publishing Company. | |

| Founded | 1865 |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United States |

The Chronicle Publishing Company was a print and broadcast media corporation headquartered in San Francisco, California that was in operation from 1865 until 2000. Owned for the whole of its existence by the de Young family, CPC was most notable for owning the namesake San Francisco Chronicle newspaper and KRON-TV, the longtime National Broadcasting Company (NBC) affiliate in the San Francisco Bay Area (San Francisco–Oakland–San Jose) television media market.[1][2][3]

History[]

The Chronicle[]

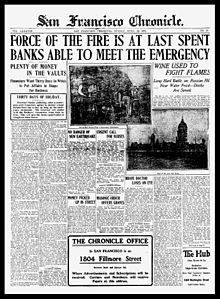

What would become Chronicle Publishing Company was formed on January 16, 1865 when teenage brothers Charles and Michael Henry "M. H." de Young published the first edition of the Daily Dramatic Chronicle, a venture funded by a borrowed $20 gold piece.[2][3][4] The paper began with a circulation of two thousand readers daily, which tripled within six months as the paper gained readership in the wake of its breaking the news of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln to San Francisco. In September 1868, the paper changed its name to the Morning Chronicle.

Over the coming decades, the Chronicle saw massive growth alongside that of San Francisco, weathering the 1880 assassination of Charles de Young in the Chronicle offices.[5] In 1890, the company built the (Old) Chronicle Building, a ten-story building at Kearny and Market Streets that was at the time the tallest building in the western United States, as well as the first to use steel framing. That building was superseded by the final company headquarters, still used by the Chronicle, which were built in 1924 at Fifth and Mission Streets.[1][6]

With the diversification of interests in the 1960s, the corporation owning the Chronicle was spun off into its own unit as Chronicle Publishing to signify a diversification of its interests outside of San Francisco.[citation needed] The second century of the company began in 1965 with the Chronicle's entering a joint operating agreement with the rival The San Francisco Examiner in which the Chronicle would publish in the mornings while The Examiner published in the afternoons.

Broadcasting[]

With the growth of television in the 1940s, Chronicle Publishing Company decided to diversify into that medium by applying for a construction permit for a television station that would be operated alongside the Chronicle. On November 5, 1949, CPC would sign on KRON-TV on VHF channel 4, which became the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) affiliate for the San Francisco Bay Area television market. This was much to the chagrin of NBC itself, which was a runner-up for the station and would desire KRON for the next half-century.[citation needed] In the 1950s, KRON would add an FM radio station (KRON-FM, now under call sign KOIT) at 96.5 MHz.

Further diversification into broadcasting came in 1975 when the sale of KRON-FM to Bonneville International allowed CPC to purchase the Meredith Corporation's WOWT-TV in Omaha, Nebraska. This was followed in 1979 with the purchase of KAKE-TV in Wichita, Kansas and in 1987 when independently owned KLBY in Colby, Kansas was purchased to increase KAKE's reach.

Outside the broadcast realm, Chronicle Publishing owned cable systems in California, Hawaiʻi, and New Mexico for several years under their Western Communications unit before those systems were sold to Tele-Communications Inc. in 1995. In the early 1990s, Chronicle Publishing launched the Bay TV cable network which was operated in conjunction with KRON and was seen on most cable systems in the Bay Area.

Publishing[]

In 1968, the Chronicle established its own book imprint in Chronicle Books, which would eventually become a successful publishing firm. The profits from Chronicle Books and the other new ventures of the company allowed the company to add to their print holdings as they purchased two newspapers, The Pantagraph of Bloomington, Illinois in 1980 and the Worcester Telegram & Gazette in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1986. In 1988, Chronicle Publishing made its final purchase in buying Motorbooks, a renowned imprint dealing with automotive books; Chronicle Publishing then established MBI Publishing Company as parent company to Classic Motorbooks and Motorbooks International.[3]

Demise[]

As late as 1993, , granddaughter of San Francisco Chronicle founder M. H. de Young and chair of Chronicle Publishing Company's board of directors, declined an offer of $800 million made by Hearst Corporation for Chronicle Publishing.[7][8] She told Editor & Publisher that the sale of the San Francisco Chronicle would take place "over [her] dead body", and was widely quoted.[9][10][11] However, with the growing consolidation of print and broadcast media in the 1990s, the other shareholding heirs of the de Young family decided to sell the assets of CPC in 1999 when the consolidation trend in the United States was at its peak.

The movement to sell was partly facilitated by the action of a special stockholders' meeting in April 1995, in which Mrs. McEvoy was ousted from the Chronicle Publishing Company board and therefore from her position as chair.[12] Although Mrs. McEvoy kept her 26.3% ownership share in the company's stock, which together with the 7% held by her son gave them a formidable one-third shareholder voting bloc if they chose to vote together, she no longer exerted direct control over the management of The Chronicle or its editorial positions, and could not retain the clout she previously held in the disposition of Chronicle Publishing Company's assets, including The Chronicle.

Over the latter half of 1999 into 2000, the units of the company were sold separately to different entities:

- San Francisco Chronicle: Hearst Corporation (longtime owners of The Examiner, which was divested upon the purchase of the Chronicle amid protests that San Francisco would be left with only one newspaper)[7][8]

- Worcester Telegram & Gazette: The New York Times Company (owners of the nearby Boston Globe)

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois): Pulitzer, Inc.

- KRON-TV: Young Broadcasting (which paid a record $820 million for the station, then disaffiliated it from NBC in the wake of a conflict with the network)

- Partner network BayTV went to Young with the sale and was folded in August 2001.

- WOWT and KAKE: LIN TV, which swapped the stations to Benedek Broadcasting for cash and that company's WWLP in Springfield, Massachusetts)

- Chronicle Books: Purchased by , Chronicle Books' editor-in-chief, son of Nan Tucker McEvoy and great-grandson of San Francisco Chronicle founder M. H. de Young[13]

- MBI Publishing: Purchased by New York City investment firm Flagship Partners, Inc.

With the exception of the Pantagraph and the book imprints, all of the former Chronicle Publishing assets have met some degree of criticism, misfortune, or both.[citation needed] Concerns about the Telegram & Gazette being pared down into a "[Boston] Globe West" arose in Worcester while Hearst's purchase of the Chronicle led to the Examiner having to reinvent itself under its new local ownership as it struggled, and down the line was sold out to private equity publishers that reduced its operations considerably. The television properties became a strain on their new owners as the Chronicle–LIN–Benedek deal pushed Benedek Broadcasting into bankruptcy with most of the company (including the former Chronicle) stations being purchased in 2002 by Gray Television. Young Broadcasting struggled in the years since purchasing KRON-TV, having sold four stations and pare down operations at KRON to keep afloat due to the heavy debt incurred by the massive purchase of the station. KRON itself also suffered due to the loss of its NBC affiliation to KNTV, and became a lower-profile news-heavy station holding an affiliation with MyNetworkTV, eventually consolidating their studios (though not ownership) within the building of their longtime rivals, ABC-owned KGO-TV. Young itself filed for bankruptcy in 2009, but emerged the next year; it sold itself to Media General in 2013, uniting it with WWLP. Nexstar Media Group purchased Media General in 2017, and KRON remains owned by that group.

Twenty-four de Young family shareholders received at least $2 billion divided among them from the sales of the Chronicle Publishing assets.[8]

See also[]

- Concentration of media ownership

- Media in the San Francisco Bay Area

- History of San Francisco

- Old Chronicle Building

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A Bay Area Institution: History of the San Francisco Chronicle". History of the San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nolte, Carl (16 June 1999). "134 Years of the Chronicle". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "A brief timeline of the San Francisco Chronicle". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. 16 June 1999. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Chronicle Mission Statement and History". History of the San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ McKee, Irving (August 1947). "The Shooting of Charles de Young". Pacific Historical Review. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 16 (3): 271–284. JSTOR 3635998.

- ^ "A Bay Area Institution: The SF Chronicle History". The SF Chronicle History. Hearst Corporation. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Seyfer, Jessie (27 July 2000). "Judge Clears Hearst Purchase in SF". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Seyfer, Jessie (28 July 2000). "Hearst Cleared To Buy SF Chronicle". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Stein, M. L. (4 December 1993). "The New Regime at The Chronicle". Editor & Publisher. Irvine, California: Duncan McIntosh Company. 126 (49): 11. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Shepard, Alicia C. (November 1999). "Family Feud". American Journalism Review. College Park, Maryland: Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland. 21 (9): 11. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Shafer, Jack; Cothran, George (26 April 1995). "Dog Bites". SF Weekly. San Francisco Newspaper Company. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Stein, M. L. (6 May 1995). "Ousted Chairman Sues". Editor & Publisher. Irvine, California: Duncan McIntosh Company. 128 (18): 14. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Farmanfarmian, Roxane (22 November 1999). "McEvoy to Buy Chronicle Books". Publishers Weekly. Boston: Cahners Business Information. 245 (47): 10. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Publishing companies established in 1865

- Companies based in San Francisco

- Defunct broadcasting companies of the United States

- Defunct newspaper companies of the United States

- Mass media companies disestablished in 2000

- Defunct companies based in the San Francisco Bay Area

- De Young family

- 1865 establishments in California

- 2000 disestablishments in California