Church window

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2019) |

Church windows are windows within cathedrals, basilicas and other church edifices. They have been a central element in church architecture since Early Christianity.

Early Christianity[]

From the beginning, Christian churches, in contrast to the ancient temples, were intended to be places for the assembling of the faithful. The temperament of the people of the East and of the South where Christian houses of worship first appeared required the admission of much light by large openings in the walls, that is, by windows. The early Christian basilicas were richly provided with large windows, placed partly in the central nave, that was raised for this purpose, partly in the side aisles and façade. In Western Europe, or rather in the countries under Roman influence, the places where the windows existed on the side aisles can no longer be identified with absolute certainty, owing to the chapels and additions that were later frequently built. In the East, however, where it was customary to select isolated sites for church buildings large windows were the rule. The place of the window was determined by the architectural membering of the basilica, the distance between two columns generally indicating the position of a window. However, there were endless exceptions to this rule in the East; thus at in Syria the windows are close together as well as over the columns; at each intercolumnar space contained two windows. In general, two or three windows united in a group, as was later the rule in Roman architecture, were even then of frequent occurrence in the early Christian architecture of Asia Minor. The form of the window is nearly everywhere the same: a rectangle that usually has a rounded top, but seldom a straight lintel. When the latter is used it is generally balanced by a semicircular arch of wedge-shaped stones. Ornamentation of the windows was hardly possible in the basilicas of Western Europe, which were generally built of brick, while the Syrian stone churches, and as an exceptional case those of the school of Spoleto, displayed rich contours and ribbon-like ornamentation.

Of that troublous period which extended to the time of Charlemagne and later until the beginning of Romanesque art, few monuments remain that give a clear conception of the window architecture then in vogue. According to Haupt's researches, the windows of the earliest Germanic churches had a round arch above, which was generally a hollowed stone. Towards the bottom these windows, strange to say, were frequently somewhat broader than above. It was not unusual in Spain, England, and France to finish the window-casement with a horseshoe arch, the upper part being formed by two stone shafts set obliquely, that is, like ribs of an arch. An example of this method is found at Deerhurst in England. The windows of this period are frequently very different on the inner and outer sides, the richer ornamentation being found on the inner side, as at Saint-Germain-des-Prés in France where there are engaged columns and ornamented .

Romanesque and Gothic[]

Up to the twelfth century the windows of the Romanesque churches had small openings for light, a sloping intrados, and an inclined sill. Originally without decoration, they later received a framework, that is, they were surrounded by a border of slender shafts as by a frame. In the further development these round shafts received small bases and capitals, the intrados was divided into rectangular intervals in which small columns were set. Gothic art adopted this framework, merely changing the round arch into a pointed one, and later replacing the rectangular intervals of the intrados by flutings. As the style grew the small capitals of the round shafts were abandoned and later the shafts themselves, by which the style returned to the simple framework. The late Gothic ceased to use even the framework and employed the sloping intrados alone, without further ornament. Naturally there were innumerable exceptions to the development sketched here only in its general features. In Romanesque art the sills had originally only a slight inclination. This gradually became greater until it became more than a right angle. Characteristic of the Romanesque style is the grouping together of two to four windows, the so-called . Above the window the flat surface of the arch remained without ornamentation or was pierced by small round windows. Romanesque art used, in addition to windows enclosed by the round arch, others surrounded by the trefoil or fan-arch, and even openings for light entirely Baroque in design, with arbitrarily curved arches. In the Gothic period the windows were longer and broader, in a number of cathedrals they almost replace the walls. Although the clustered window with three openings did not entirely disappear, yet it was more customary to use two narrow windows combined by a common shaft and a common pointed arch above them. The shafts grew constantly more slender and a circular arch was introduced under the pointed arch. This led in the course of time to the appearance of tracery which was so largely used in window ornamentation in the Gothic period that it became almost the most important consideration in the construction of windows. Tracery is formed by setting together separate parts of a circle called foils; their points of contact are named cusps. By means of tracery the pointed arches of the windows were constantly filled with new forms and devices, simple in the early Gothic, artificial and confused the more the style developed, until finally in the late Gothic or Flamboyant style the wavy tracery was used which no longer consisted of circles and segments of circles but assumed forms comparable to flames, a style particularly in vogue in England and France. Towards the end of the Gothic period greater sobriety of form came into use and tracery began to decline. The elaboration undergone by the tracery was also shared by the shafts of the windows and intrados. Undivided at first they gradually received richer contours and were separated into main and subordinate pillars. The earliest tracery of which the date is known is that still existing in the choir chapels of the Reims Cathedral (1211).

Renaissance[]

The Renaissance returned to the round-arched clustered windows of the Romanesque style, particularly in brick buildings. Still light openings with slender connexions between them and enclosed in rectangular frames are to found in houses built of stone, particularly in the late Renaissance. They generally received as ornament, in imitation of antiquity, a frame of broad profile, which at the height of the Renaissance was generally surrounded by two supports, pilasters, or columns, and the entablature rested upon these. Framing of this kind has many forms, but the following are the most noticeable styles:

- The opening for light is enclosed by a frame running parallel to it which has the profile of an architrave and generally has a horizontal cornice as a finish at the top (simple framework);

- instead of the simple framework supports, pillars, pilasters, or columns, are arranged on the perpendicular sides, which carry above them a straight entablature, a gable-cornice, or an archivolt (truss-frame);

- the most frequent and most artistic form is the combination of the simple frame and the truss-frame, from which spring the most varied combinations, as sometimes the simple frame encloses a truss-frame, or the reverse, or sometimes two truss-frames are combined with each other (combined frame);

- abandoning frames and supports the openings for light are surrounded only by quarry-faced ashlar. In costly buildings the windows had an ornamental finish below, either a resting on consoles, or a panel surrounded by a frame or carried by supports.

Baroque[]

The Baroque added to the round-arched and rectangular light- openings those in the shape of a basket-handle arch and even of an oval shape, and sought to enrich them by drawing in the corners and by curving the sides in and out. This led to the appearance of a great variety of lines the number and lack of repose of which is characteristic of the Baroque. The framing which the Renaissance had given the windows remained customary during the Baroque period, but in agreement with the entire development of the style they were augmented, were more artificial, and had less repose. The most frequently used was the flat or profiled framing, in which the cornice no longer ran parallel to the light- opening, but assumed an independent arbitrary form; at times the frame was interrupted by quarry-faced ashlar. The support-framing was seldom used, the combined framing was changed so that the frames were no longer laid one by the other, but one over the other, only a small part of the under one being visible on the two sides. The part of the frame above the window received a rich development; it was generally either a horizontal cornice or a gable cornice; where the windows were arched it also followed the curved line, with the result of an unlimited variety of artistic forms.

Classical[]

Classicism first abandoned the combination of the two framings, it next gave up the truss-frame, so that finally nothing remained of the former variety but the simple unadorned frame with or without a top piece. As regards the Louis XVI and Empire styles the simplifying of the frame was retained and ornamentation was limited almost exclusively to the top-piece, which was supported by consoles and adorned with garlands of fruit and other ornaments in imitation of the antique.

See also[]

- Stained glass windows

- Church architecture

- Lancet window

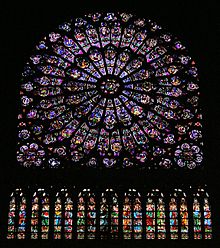

- Rose window

References[]

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kleinschmidt, Beda (1913). "Windows in Church Architecture". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kleinschmidt, Beda (1913). "Windows in Church Architecture". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Church architecture