Ciphertext

In cryptography, ciphertext or cyphertext is the result of encryption performed on plaintext using an algorithm, called a cipher.[1] Ciphertext is also known as encrypted or encoded information because it contains a form of the original plaintext that is unreadable by a human or computer without the proper cipher to decrypt it. Thus preventing loss of sensitive information via hacking. Decryption, the inverse of encryption, is the process of turning ciphertext into readable plaintext. Ciphertext is not to be confused with codetext because the latter is a result of a code, not a cipher.

Conceptual underpinnings[]

Let be the plaintext message that Alice wants to secretly transmit to Bob and let be the encryption cipher, where is a cryptographic key. Alice must first transform the plaintext into ciphertext, , in order to securely send the message to Bob, as follows:

In a symmetric-key system, Bob knows Alice's encryption key. Once the message is encrypted, Alice can safely transmit it to Bob (assuming no one else knows the key). In order to read Alice's message, Bob must decrypt the ciphertext using which is known as the decryption cipher,

Alternatively, in a non-symmetric key system, everyone, not just Alice and Bob, knows the encryption key; but the decryption key cannot be inferred from the encryption key. Only Bob knows the decryption key and decryption proceeds as

Types of ciphers[]

The history of cryptography began thousands of years ago. Cryptography uses a variety of different types of encryption. Earlier algorithms were performed by hand and are substantially different from modern algorithms, which are generally executed by a machine.

Historical ciphers[]

Historical pen and paper ciphers used in the past are sometimes known as classical ciphers. They include:

- Substitution cipher: the units of plaintext are replaced with ciphertext (e.g., Caesar cipher and one-time pad)

- Polyalphabetic substitution cipher: a substitution cipher using multiple substitution alphabets (e.g., Vigenère cipher and Enigma machine)

- Polygraphic substitution cipher: the unit of substitution is a sequence of two or more letters rather than just one (e.g., Playfair cipher)

- Transposition cipher: the ciphertext is a permutation of the plaintext (e.g., rail fence cipher)

Historical ciphers are not generally used as a standalone encryption technique because they are quite easy to crack. Many of the classical ciphers, with the exception of the one-time pad, can be cracked using brute force.

Modern ciphers[]

Modern ciphers are more secure than classical ciphers and are designed to withstand a wide range of attacks. An attacker should not be able to find the key used in a modern cipher, even if he knows any amount of plaintext and corresponding ciphertext. Modern encryption methods can be divided into the following categories:

- Private-key cryptography (symmetric key algorithm): the same key is used for encryption and decryption

- Public-key cryptography (asymmetric key algorithm): two different keys are used for encryption and decryption

In a symmetric key algorithm (e.g., DES and AES), the sender and receiver must have a shared key set up in advance and kept secret from all other parties; the sender uses this key for encryption, and the receiver uses the same key for decryption. In an asymmetric key algorithm (e.g., RSA), there are two separate keys: a public key is published and enables any sender to perform encryption, while a private key is kept secret by the receiver and enables only him to perform correct decryption.

Symmetric key ciphers can be divided into block ciphers and stream ciphers. Block ciphers operate on fixed-length groups of bits, called blocks, with an unvarying transformation. Stream ciphers encrypt plaintext digits one at a time on a continuous stream of data and the transformation of successive digits varies during the encryption process.

Cryptanalysis[]

Cryptanalysis is the study of methods for obtaining the meaning of encrypted information, without access to the secret information that is normally required to do so. Typically, this involves knowing how the system works and finding a secret key. Cryptanalysis is also referred to as codebreaking or cracking the code. Ciphertext is generally the easiest part of a cryptosystem to obtain and therefore is an important part of cryptanalysis. Depending on what information is available and what type of cipher is being analyzed, crypanalysts can follow one or more attack models to crack a cipher.

Attack models[]

- Ciphertext-only: the cryptanalyst has access only to a collection of ciphertexts or codetexts

- Known-plaintext: the attacker has a set of ciphertexts to which he knows the corresponding plaintext

- Chosen-plaintext attack: the attacker can obtain the ciphertexts corresponding to an arbitrary set of plaintexts of his own choosing

- Batch chosen-plaintext attack: where the cryptanalyst chooses all plaintexts before any of them are encrypted. This is often the meaning of an unqualified use of "chosen-plaintext attack".

- Adaptive chosen-plaintext attack: where the cryptanalyst makes a series of interactive queries, choosing subsequent plaintexts based on the information from the previous encryptions.

- Chosen-ciphertext attack: the attacker can obtain the plaintexts corresponding to an arbitrary set of ciphertexts of his own choosing

- Adaptive chosen-ciphertext attack

- Indifferent chosen-ciphertext attack

- Related-key attack: like a chosen-plaintext attack, except the attacker can obtain ciphertexts encrypted under two different keys. The keys are unknown, but the relationship between them is known; for example, two keys that differ in the one bit.

The ciphertext-only attack model is the weakest because it implies that the cryptanalyst has nothing but ciphertext. Modern ciphers rarely fail under this attack.[3]

Famous ciphertexts[]

- The Babington Plot ciphers

- The Shugborough inscription

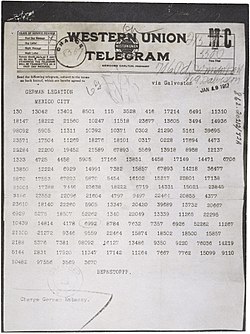

- The Zimmermann Telegram

- The Magic Words are Squeamish Ossifrage

- The cryptogram in "The Gold-Bug"

- Beale ciphers

- Kryptos

- Zodiac Killer ciphers

See also[]

- Books on cryptography

- Cryptographic hash function

- Frequency analysis

- RED/BLACK concept

- Category:Undeciphered historical codes and ciphers

References[]

- ^ Berti, Hansche, Hare (2003). Official (ISC)² Guide to the CISSP Exam. Auerbach Publications. pp. 379. ISBN 0-8493-1707-X.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b van Tilborg, Henk C.A. (2000). Fundamentals of Cryptology. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 0-7923-8675-2.

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (28 August 2000). Secrets & Lies. Wiley Computer Publishing Inc. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-471-25311-1.

Further reading[]

| Look up ciphertext in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ciphertexts. |

- Helen Fouché Gaines, “Cryptanalysis”, 1939, Dover. ISBN 0-486-20097-3

- David Kahn, The Codebreakers - The Story of Secret Writing (ISBN 0-684-83130-9) (1967)

- Abraham Sinkov, Elementary Cryptanalysis: A Mathematical Approach, Mathematical Association of America, 1968. ISBN 0-88385-622-0

- Cryptography