City of Hope (film)

| City of Hope | |

|---|---|

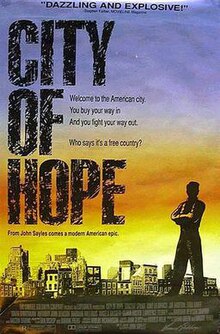

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Sayles |

| Screenplay by | John Sayles |

| Produced by | Harold Welb John Sloss |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | John Sayles |

| Music by | Mason Daring |

Production companies | Esperanza Films The Samuel Goldwyn Company |

| Distributed by | Esperanza Films The Samuel Goldwyn Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 129 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3 million[1] |

| Box office | $1.3 million (US).[1] |

City of Hope is a 1991 American drama film written, directed, and edited by John Sayles. The film features Vincent Spano, Stephen Mendillo and Chris Cooper.

Plot[]

Nick Rinaldi is the aimless son of corrupt property developer Joe Rinaldi, who is determined to provide for Nick after the death in Vietnam of the Rinaldi's older son. Rinaldi owns a derelict apartment building that blocks the construction of a mixed-use development that the equally corrupt mayor pushes hard for to boost his re-election chances. Bored at the no-show job organized by his father, Nick quits and turns to crime to assuage his debts and drug addiction. Joe is introduced arguing with idealistic alderman Wynn (Morton) about hiring more African-Americans, which Rinaldi is hesitant to do for political reasons. Nick joins his friends, low-rent thugs Bobby and Zip, who work for small-time hoodlum Carl. Carl sets the men up with access to a local electronics store. Unbeknownst to the men, the owner is a close friend of Joe's. While breaking into the store, they are thwarted by the store's new security guard (who is Wynn's brother-in-law), who threatens to shoot them despite his gun being fake. Bobby and Zip are arrested and jailed while Nick flees. While the pair sit in jail, annoyed by delusional homeless man Asteroid, Nick begins to fall for Angela, a waitress at a local restaurant, who has a child by Rizzo, a young and hot-headed policeman. Rizzo, who stalks his ex-wife, is infuriated that Rinaldi is pursuing Angela, and hassles two young black boys as a result. The boys, deciding that they may as well live up to the way the police portray them, attack a professor jogging in a nearby park, later falsely claiming that the professor made advances toward them. Wynn privately expresses doubt in the story of the boys, but worries of his perception from the black community if he does not stand with the boys, especially from Malik, an intense composite character that represents black power, Nation of Islam, and Pan-Africanist ideals.

Nick's involvement in the botched robbery is revealed by Carl, who blackmails Joe into agreeing to allow one of Carl's henchmen to flood and deliberately set a fire in Rinaldi's slum (so that it may be cleared for the mayor's project) in exchange for the police dropping Nick from their warrant lists. Joe's relationship with Nick also takes a sour turn when Nick learns that his older brother, who Nick has been in the shadow of his whole life, was deployed to Vietnam as an alternative to prison for injuring a young woman as a result of a DUI. Elsewhere, community organizers rope Wynn into defending the stories of the boys that attacked the jogger. Realizing that the accused pedophile is one of his old college professor coworkers, Wynn visits him privately to encourage the man to drop the charges, arguing that if he goes public, the accusations of pedophilia will remain linked to his name. Carl's henchman torches Joe's apartment building, but Joe quickly realizes that the plan has gone awry as a young Hispanic woman and her baby, squatting in a part of the building thought by Joe to be abandoned, perish in the blaze. Wynn visits Desmond, one of the young boys involved in the jogger attack, and learns that the boys were lying. However, before he can act, the black community center reports that the professor agreed to drop the charges against the boys.

Wynn, now fully embracing the city's ethos, leads a contingent of the black community to disrupt a fundraising dinner for the mayor. Desmond visits the home of the professor that the boys attacked, claiming he saw his address in the paper. The professor initially brushes him away, but Desmond apologizes for what happened and asks if he can accompany the man on a run, discovering that he is a professor of urban relations. Nick runs into a drunken Rizzo, who confronts Nick, shooting at him after the two men get into a scuffle. Rizzo's old patrol partner picks him up, and the new trainee, a Hispanic man, inquires whether Rizzo's gun is legal. After the new officer refuses to overlook Rizzo's illegal conduct, Rizzo grows angry as the car drives off. Joe finds Nick in the new property development, severely wounded. Joe calls for help, but the only person who hears his cries is Asteroid, who repeats them frantically to an empty street.

Cast[]

- Vincent Spano as Nick Rinaldi

- Barbara Williams as Angela

- Stephen Mendillo as Yoyo

- Chris Cooper as Riggs

- Tony Lo Bianco as Joe Rinaldi

- Joe Morton as Wynn

- Jace Alexander as Bobby

- Todd Graff as Zip

- John Sayles as Carl

- Frankie Faison as Levonne

- Gloria Foster as Jeanette

- Tom Wright as Malik

- Angela Bassett as Reesha

- David Strathairn as Asteroid

- Gina Gershon as Laurie Rinaldi

- Maggie Renzi as Connie

- Tony Denison as Rizzo

Production[]

Sayles filmed the movie in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati.[2]

Reception[]

Critical response[]

Film critic Roger Ebert wrote, "City of Hope is a powerful film, and an angry one. It is impossible not to find echoes of its despair on the front pages every day. It asks a hard question: Is it possible for a good person to prevail in a corrupt system, just simply because right is on his side? The answer, in the short run, is that power is stronger than right. The notion of a long run, of course, is all that keeps hope alive."[3]

The staff at Variety magazine wrote, "John Sayles' ambitious, wide-ranging study of corruption and community in a small Eastern city has as many parallel plots and characters as Hill Street Blues, while at the same time having a richness of theme and specificity of vision more common to serious cinema."[4]

Film critics Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat wrote about the varied aspects of the film, writing, "Through the diverse activities of over three dozen characters in this film, we see some of the major challenges of urban living including crime, political chicanery, the patronage system, the demise of the work ethic, the rapacious side of capitalism, and the high cost of civic apathy. City of Hope helps us see that community is enriched or torn apart by the ethical decisions we make every day."[5]

The film holds a 94% on review aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes, based on 17 reviews.[6]

Accolades[]

Wins

- Tokyo International Film Festival: Tokyo Grand Prix; John Sayles; 1991.

- Political Film Society: PFS Award Democracy and Special Award; 1992.

- : KCFCC Award; Best Screenplay, John Sayles; 1992.

- Independent Spirit Awards: Independent Spirit Award; Best Supporting Male, David Strathairn; 1992.

Nominations

- Belgian Syndicate of Cinema Critics; Grand Prix; 1994.

- Deauville Film Festival: Critics Award; John Sayles; 1991.

- Independent Spirit Awards: Independent Spirit Award; Best Feature, Sarah Green and Maggie Renzi; 1992.

References[]

- ^ a b Gerry Molyneaux, "John Sayles, Renaissance Books, 2000 p. 195.

- ^ Wheeler, Lonnie (November 25, 1990). "John Sayles Finds His "City of Hope" in Cincinnati". The New York Times.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 25, 1991). "City Of Hope". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ "City of Hope". Variety. December 31, 1990.

- ^ Brussat, Frederic and Mary Ann. Spirituality & Practice, film review, 1970–2007. Accessed: March 1, 2008.

- ^ "City of Hope (1991)". Retrieved August 20, 2021.

External links[]

- 1991 films

- English-language films

- 1990s political drama films

- American independent films

- American political drama films

- American films

- Films directed by John Sayles

- Films set in New Jersey

- Films shot in Ohio

- Films with screenplays by John Sayles

- The Samuel Goldwyn Company films

- Films scored by Mason Daring

- 1991 independent films

- 1991 drama films