Clyde Workers' Committee

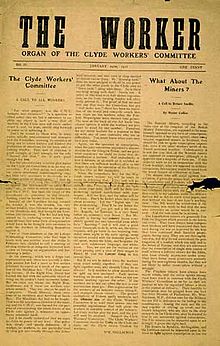

January 1916 edition of The Worker | |

| Successor | Scottish Workers' Committee |

|---|---|

| Formation | October 1915 |

| Founded at | Glasgow |

| Dissolved | 1916 |

Membership | 200 - 300 |

Chairman | William Gallacher |

Treasurer | David Kirkwood |

Formerly called | Central Labour Withholding Committee |

The Clyde Workers Committee was formed to campaign against the Munitions Act. It was originally called the Labour Withholding Committee.[1] The leader of the CWC was Willie Gallacher, who was jailed under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 together with John Muir for an article in the CWC journal The Worker criticising the First World War.

Formation[]

The committee originated in a strike in February 1915 at G. & J. Weir. Due to labour shortages during the war, the company had employed some workers from America, but were paying them more than the Scottish staff. The shop stewards at the factory organised a walk-out in support of equal pay, and more factories joined the dispute over the next few weeks, until workers at 25 different factories were on strike.[2]

Most of the workers were members of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE), but the union leadership, both locally and nationally, opposed the strike. In order to defend the strike, about two hundred shop stewards and supporters formed the informal Central (or Clyde) Labour Withholding Committee, which was constituted as the Clyde Workers' Committee in October 1915.[2][3]

The committee met weekly, and included numerous people who later became prominent socialists and communists. These included Gallacher, Tom Bell, David Kirkwood, John Maclean, Arthur MacManus, Harry McShane and Jimmy Maxton.[2][4][5] Many of the leading figures were members of the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), but others were involved with the British Socialist Party, the Independent Labour Party, or had no previous political involvement, the general approach being broadly.[5]

Early campaigns – The Glasgow Rent Strikes[]

The initial demands for higher pay were largely successful,[6] and the committee took up the matter of high rents - an influx of workers to staff the factories producing war materials had pushed up rents.[7] Opposition to this was led by a group of working-class women, including Mary Barbour, Mary Burns Laird, Helen Crawfurd, Agnes Dollan and Mary Jeff, and culminated in a rent strike of 25,000 tenants by October 1915.[8] The committee threatened to call a general strike on the matter, and the government responded by introducing the national Rent Restriction Act.[9]

Policy[]

The committee called for joint control of factories by workers and management, ultimately leading to the overthrow of the wage system, to produce industrial democracy.[3] It was suspicious of the full-time leadership of the trade unions, and passed a resolution stating that they would only support them when their own committee decisions concorded.[2] Although Maclean, James D. MacDougall and Peter Petroff urged the group to adopt a policy opposing the war, the SLP members refused to allow discussion of this, preferring to stick solely to industrial and democratic matters.[5]

In order to propagate their views, the committee published a weekly newspaper, The Worker,[10] edited by John William Muir.[11]

Arrests and deportations[]

In December 1915, David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson, leading figures in the Liberal Party and Labour Party, travelled to Glasgow to address a meeting of workers at St Andrew's Hall. This was poorly received, particularly by supporters of Maclean, who barracked the speakers. Press accounts of the meeting were officially censored, but two local socialist newspapers, Forward and Maclean's own publication, Vanguard, were either unaware of this or unwilling to co-operate.[12] In response, the government banned the two publications and seized copies of their current issues. On 2 February, The Worker was also banned, on the grounds that it had printed an article by Maclean entitled "Should the workers arm?", even though the article had concluded that they should not. Police raided the SLP offices where the paper was produced and broke the printing presses, and arrested Maclean, Gallacher, Muir and Walter Bell.[11]

In February 1916, David Kirkwood, the treasurer of the committee and a shop steward at William Beardmore and Company, was warned that he would be sacked if he spoke to new employees. The following month, he resigned his union post, and a strike at the factory ensued. This soon spread, and was denounced by the ASE leadership.[13] Kirkwood and three other shop stewards (J. Faulds, James Haggerty, Sam Shields and Wainright) were court-martialled in their absence and forcibly deported to Edinburgh,[14] along with two other committee members: T. M. Messer, and MacManus, who had not yet been involved in the strike.[11] They were soon followed by Harry Glass, Robert Bridges and Kennedy from Weir's.[15] A large demonstration on Glasgow Green was addressed by Maxton and MacDougall, who were also taken to Edinburgh and imprisoned in Calton Jail.[16] Maclean, Gallacher, Bell and Weir were tried on charges including sedition, and were all found guilty. All except Maclean pleaded guilty and were apologetic; Maclean sang the Red Flag and was sentenced to penal servitude.[11]

Later activities[]

With all the committee's leading figures imprisoned or deported by the end of 1916,[2] less central figures, such as Jock McBain, came to the fore.[17] Only sporadic industrial action took place, and the committee focused on fundraising for the deported leaders.[17] The committee collapsed,[12] inspiring a less influential successor, the Scottish Workers' Committee,[10] and also the , organised on a similar basis and led by J. T. Murphy.[2] These ultimately became part of the Shop Stewards' and Workers' Committees.[18]

References[]

- ^ Clydeside resistance to dilution accessed 17 June 2012

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Ralph Darlington, The Political Trajectory of J.T. Murphy, pp.14-15

- ^ Jump up to: a b Walter Kolvenbach, Employee Councils in European Companies, p.288

- ^ Maggie Craig, When the Clyde Ran Red

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Martin Crick, The History of the Social-Democratic Federation, p.275

- ^ William Knox, James Maxton, p.20

- ^ Ian F. W. Beckett, The Making of the First World War

- ^ Jill Liddington, The Road to Greenham Common: Feminism and Anti-militarism in Britain Since 1820, p.114

- ^ L. J. Macfarlane, The British Communist Party, p.41

- ^ Jump up to: a b James Klugmann, History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Formation and early years, 1919-1924, p.23

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Keith Ewing and C. A. Gerty, The Struggle for Civil Liberties, pp.73-78

- ^ Jump up to: a b B. J. Ripley and J. McHugh, John Maclean, pp.92-95

- ^ Adrian Gregory, The Last Great War

- ^ A. T. Lane, Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders, Volume 1, pp.489-490

- ^ Tom Bell, John Maclean, a fighter for freedom, p.58

- ^ John MacLeod, River of Fire: The Clydebank Blitz

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knox, William (1984). Scottish Labour Leaders 1918-1939. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing Company. pp. 168–170. ISBN 0906391407.

- ^ Patrick Renshaw, The Wobblies, p.223

External links[]

- Opposition to World War I

- History of labour relations in Scotland

- Red Clydeside

- 1915 establishments in Scotland

- 1915 in economics

- 1915 in politics