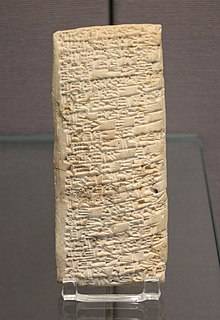

Complaint tablet to Ea-nasir

The complaint tablet to Ea-nasir (UET V 81)[1] is a clay tablet that was sent to ancient Ur, written c. 1750 BC. It is a complaint to a merchant named Ea-nasir from a customer named Nanni. Written in Akkadian cuneiform, it is considered to be the oldest known written complaint. It is currently kept in the British Museum.[2]

Ea-nasir travelled to Dilmun to buy copper and returned to sell it in Mesopotamia. On one particular occasion, he had agreed to sell copper ingots to Nanni. Nanni sent his servant with the money to complete the transaction.[3] The copper was sub-standard and not accepted. In response, Nanni created the cuneiform letter for delivery to Ea-nasir. Inscribed on it is a complaint to Ea-nasir about a copper delivery of the incorrect grade, and issues with another delivery;[4] Nanni also complained that his servant (who handled the transaction) had been treated rudely. He stated that, at the time of writing, he had not accepted the copper, but had paid the money for it.

Description[]

The tablet is 11.6 centimetres (4.6 in) high, 5 centimetres (2.0 in) wide, 2.6 centimetres (1.0 in) thick, and slightly damaged.[4]

Acquisition[]

The tablet was discovered and acquired by Sir Leonard Woolley, leading a joint expedition with the University of Pennsylvania and British Museum from 1922 to 1934 in the Sumerian city of Ur.[4][5]

Other tablets[]

Other tablets have been found in the ruins believed to be Ea-nasir's dwelling. These include a letter from a man named Arbituram who complained he had not received his copper yet, while another says he was tired of receiving bad copper.[6][7]

References[]

Works cited[]

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (1967). Letters From Mesopotamia: Official, Business, and Private Letters on Clay Tablets from Two Millennia. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Oppenheim translation of complaint tablet, pg82-83

- Baraniuk, Chris (2 March 2015). "Ancient customer-feedback technology lasts millennia". New Scientist.

- Kruszelnicki, Karl S. (24 March 2015). "The oldest known complaint letter". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Kalinauskas, Nadine (10 March 2015). "Clay tablet with oldest recorded customer-service complaint on display at the British Museum". Yahoo News Canada.

- McNally, Victoria (27 February 2015). "Ancient Babylonians Were Just Like Us, Complained About Poor Service From Retailers". The Mary Sue.

- Wheaton, Oliver (5 March 2015). "Believe it or not, this carving is actually a 3,750-year-old customer service complaint". Metro.

- "Bluff The Listener". NPR. 7 March 2015.

Footnotes[]

- ^ Figulla, H. H.; Martin, W. J., eds. (1953). Letters and Business Documents of the Old Babylonian Period. Ur Excavations: Texts. Vol. V. London: British Museum Press. p. 5, Pl. XIV.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Hyken, Shep. "Oldest Customer Service Complaint Discovered: A Lesson from Ancient Babylon". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ^ Crawford, Harriet (July 2015). "Sir Leonard Woolley and Ur of the Chaldees". The Bible and Interpretation.

- ^ a b c "British Museum – tablet". British Museum.

- ^ "Collections Online | British Museum".

- ^ Killgrove, Kristina. "Meet The Worst Businessman Of The 18th Century BC". Forbes. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Leemans, W.F. (1960). Foreign trade in the Old Babylonian period: as revealed by texts from southern Mesopotamia. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 40-41.

External links[]

- M. Rice The Archaeology of the Arabian Gulf, p. 276.

- Leemans, W. F. (1960). "Ur: Time of Rim-Sin". Foreign Trade in the Old Babylonian Period: As Revealed by Texts from Southern Mesopotamia. Studia et Documenta ad Iura Orientis Antiqui Pertinentia. Vol. 4. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 39–40., translation by W.F. Leemans

- Clay tablets

- Mesopotamian literature

- Middle Eastern objects in the British Museum

- Customer service

- 18th-century BC works

- Copper industry

- Akkadian inscriptions