Conversion therapy

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender |

|

|

Conversion therapy is the pseudoscientific practice of attempting to change an individual's sexual orientation from homosexual or bisexual to heterosexual or their gender identity from transgender or nonbinary to cisgender using psychological, physical, or spiritual interventions. There is no reliable evidence that sexual orientation or gender identity can be changed, and medical institutions warn that conversion therapy practices are ineffective and potentially harmful.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] [9][10] Medical, scientific, and government organizations in the United States and the United Kingdom have expressed concern over the validity, efficacy and ethics of conversion therapy.[11][12][13][14][15][16] Various jurisdictions around the world have passed laws against conversion therapy.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) encourages legislation which would prohibit psychiatric treatment "based on the a priori assumption that diverse sexual orientations and gender identities are mentally ill and should change."[17] and describes attempts to change a person's sexual orientation by practitioners as unethical.[6] The APA also states that the advancement of conversion therapy may cause social harm by disseminating unscientific views about sexual orientation.[12] In 2001, United States Surgeon General David Satcher issued a report stating that "there is no valid scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed".[18]

Contemporary clinical techniques used in the United States have been limited to counseling, visualization, social skills training, psychoanalytic therapy, and spiritual interventions such as "prayer and group support and pressure",[19] though there are some reports of aversive treatments through unlicensed practice as late as the early 2000s.[20][21][22] The term reparative therapy has been used as a synonym for conversion therapy in general,[11] but it has been argued that, strictly speaking, it refers to a specific kind of therapy associated with the psychologists Elizabeth Moberly and Joseph Nicolosi.[23] Techniques that were used in the past in the United States and Western Europe have included ice-pick lobotomies;[3][4][24][25][26][27] chemical castration with hormonal treatment;[28] aversive treatments, such as "the application of electric shock to the hands and/or genitals"; "nausea-inducing drugs ... administered simultaneously with the presentation of homoerotic stimuli"; and masturbatory reconditioning.

The National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH) was the main organization advocating for conversion therapy. Fundamentalist Christian groups, and some other organizations, have used religious justification for the therapy.[4]

History[]

The history of conversion therapy can be divided broadly into three periods: an early Freudian period; a period of mainstream approval of conversion therapy, when the mental health establishment became the "primary superintendent" of sexuality; and a post-Stonewall period where the mainstream medical profession disavowed conversion therapy.[4]

During the earliest parts of psychoanalytic history, analysts granted that homosexuality was non-pathological in certain cases, and the ethical question of whether it ought to be changed was discussed. By the 1920s analysts assumed that homosexuality was pathological and that attempts to treat it were appropriate, although psychoanalytic opinion about changing homosexuality was largely pessimistic. Those forms of homosexuality that were considered perversions were usually held to be incurable. Analysts' tolerant statements about homosexuality arose from recognition of the difficulty of achieving change. Beginning in the 1930s and continuing for roughly twenty years, major changes occurred in how analysts viewed homosexuality, which involved a shift in the rhetoric of analysts, some of whom felt free to ridicule and abuse their gay patients.[29]

Europe[]

Eugen Steinach[]

Eugen Steinach was a Viennese endocrinologist who transplanted testicles from straight men into gay men in attempts to change their sexual orientation,[30] stating that his research had "thrown a strong light on the organic determinants of homo-eroticism". Steinach's method was doomed to failure because the immune system rejects transplanted glands, and was eventually exposed as ineffective and often harmful.[31]

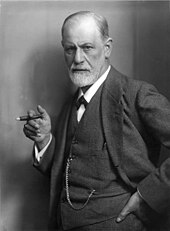

Sigmund Freud[]

Sigmund Freud was a physician and the founder of psychoanalysis. Freud stated that homosexuality could sometimes be removed through hypnotic suggestion,[32] and was influenced by Eugen Steinach.[33] Freud cautioned that Steinach's operations would not necessarily make possible a therapy that could be generally applied, arguing that such transplant procedures would be effective in changing homosexuality in men only in cases in which it was strongly associated with physical characteristics typical of women, and that probably no similar therapy could be applied to lesbianism.[34][35]

Freud's main discussion of female homosexuality was the 1920 paper "The Psychogenesis of a Case of Homosexuality in a Woman", which described his analysis of a young woman who had entered therapy because her parents were concerned that she was a lesbian and wanted the condition changed. In Freud's view, the prognosis was unfavourable because of the circumstances under which she entered therapy, and because homosexuality was not an illness or neurotic conflict. Freud wrote that changing homosexuality was difficult and possible only under unusually favourable conditions, observing that "in general to undertake to convert a fully developed homosexual into a heterosexual does not offer much more prospect of success than the reverse".[36] Success meant making heterosexual feeling possible, not eliminating homosexual feelings.[37]

Gay people could seldom be convinced that heterosexual sex would provide them with the same pleasure they derived from homosexual sex. Patients often wanted to become heterosexual for reasons Freud considered superficial, including fear of social disapproval, an insufficient motive for change. Some might have no real desire to become heterosexual, seeking treatment only to convince themselves that they had done everything possible to change, leaving them free to return to homosexuality after the failure they expected.[38][39][40]

In 1935, a mother asked Freud to treat her son. Freud replied in a letter that later became famous:[41]

I gather from your letter that your son is a homosexual. ... it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation; it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development. ... By asking me if I can help [your son], you mean, I suppose, if I can abolish homosexuality and make normal heterosexuality take its place. The answer is, in a general way we cannot promise to achieve it. In a certain number of cases we succeed in developing the blighted germs of heterosexual tendencies, which are present in every homosexual; in the majority of cases it is no more possible. It is a question of the quality and the age of the individual. The result of treatment cannot be predicted.[42]

Sándor Ferenczi[]

Sándor Ferenczi was an influential psychoanalyst. Ferenczi hoped to cure some kinds of homosexuality completely, but was content in practice with reducing what he considered gay men's hostility to women, along with the urgency of their homosexual desires, and with trying to make them attracted to and potent with women. In his view, a gay man who was confused about his sexual identity and felt himself to be "a woman with the wish to be loved by a man" was not a promising candidate for cure. Ferenczi believed that complete cures of homosexuality might become possible in the future when psychoanalytic technique had been improved.[29][43][44]

Anna Freud[]

Daughter of Sigmund Freud, Anna Freud became an influential psychoanalytic theorist in the UK.[45]

Anna Freud reported the successful treatment of homosexuals as neurotics in a series of unpublished lectures. In 1949 she published "Some Clinical Remarks Concerning the Treatment of Cases of Male Homosexuality" in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis. In her view, it was important to pay attention to the interaction of passive and active homosexual fantasies and strivings, the original interplay of which prevented adequate identification with the father. The patient should be told that his choice of a passive partner allows him to enjoy a passive or receptive mode, while his choice of an active partner allows him to recapture his lost masculinity. She claimed that these interpretations would reactivate repressed castration anxieties, and childhood narcissistic grandiosity and its complementary fear of dissolving into nothing during heterosexual intercourse would come with the renewal of heterosexual potency.[29]

Anna Freud in 1951 published "Clinical Observations on the Treatment of Male Homosexuality" in The Psychoanalytic Quarterly and "Homosexuality" in the American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA) Bulletin. In these articles, she insisted on the attainment of full object-love of the opposite sex as a requirement for cure of homosexuality. In 1951 she gave a lecture about treatment of homosexuality which was criticised by Edmund Bergler, who emphasised the oral fears of patients and minimized the importance of the phallic castration fears she had discussed.[29]

Anna Freud recommended in 1956 to a journalist who was preparing an article about psychoanalysis for The Observer of London that she not quote Freud's letter to the American mother, on the grounds that "nowadays we can cure many more homosexuals than was thought possible in the beginning. The other reason is that readers may take this as a confirmation that all analysis can do is to convince patients that their defects or 'immoralities' do not matter and that they should be happy with them. That would be unfortunate."[45]

Melanie Klein[]

Melanie Klein was a pupil of Ferenczi. Her seminal book The Psycho-Analysis of Children, based on lectures given to the British Psychoanalytical Society in the 1920s, was published in 1932. Klein claimed that entry into the Oedipus Complex is based on mastery of primitive anxiety from the oral and anal stages. If these tasks are not performed properly, developments in the Oedipal stage will be unstable. Complete analysis of patients with such unstable developments would require uncovering these early concerns. The analysis of homosexuality required dealing with paranoid trends based on the oral stage. The Psycho-Analysis of Children ends with the analysis of Mr. B., a gay man. Klein claimed that he illustrated pathologies that enter into all forms of homosexuality: a gay man idealizes "the good penis" of his partner to allay the fear of attack he feels due to having projected his paranoid hatred onto the imagined "bad penis" of his mother as an infant. She stated that Mr. B.'s homosexual behaviour diminished after he overcame his need to adore the "good penis" of an idealized man. This was made possible by his recovering his belief in the good mother and his ability to sexually gratify her with his good penis and plentiful semen.[29]

Vote by European parliament in March 2018[]

In March 2018, a majority of 435 against 109 representatives in the European parliament passed a resolution condemning conversion therapy and urging European Union member states to ban the practice.[46][47][48]

Albania[]

In May 2020, Albania became the third European country (after Malta (2016) and Germany (2020)) to ban conversion therapy or any pseudo-therapeutic attempts to change a person's sexual orientation or gender identity.[49][50][51][52]

Germany[]

On 7 May 2020, German parliament Bundestag banned nationwide conversion therapy for minors until 18 years and forbids advertising of conversion therapy. It also forbids conversion therapy for adults, if they are decided by force, fraud or pressure.[53]

Malta[]

On 6 December 2016, Malta became the first country in the European Union to prohibit the use of conversion therapy.[54][55][56]

United Kingdom[]

Conversion therapy is legal in the United Kingdom.[57] The Conservative Party promised in 2018 as part of its LGBT Action Plan to make it illegal. On 8 March (International Women's Day) 2021, the UK parliament held a debate on conversion therapy where Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Equalities Kemi Badenoch gave no timeline for legislation, did not use the word ban, suggested there may be religious exemptions and did not mention adult conversion therapy. In response to accusations of lack of action by the government, a member of the government's LGBT+ advisory panel, Jayne Ozanne, resigned.[58][59] In April 2021, after another two members of the panel quit over lack of action on banning conversion therapy, Liz Truss, the equalities minister, disbanded the panel.[60] On 11 May, in the Queen's Speech, the government stated its intention that conversion therapy should become a banned practice throughout England and Wales.[61]

Australia[]

The Government of Victoria announced in 2016 that it would be legislating to ban all LGBTQI conversion therapy.[62][63][64] The new law began operating in February 2017[65] and allows the Health Complaints Commissioner to act against any health professional engaged in practices that are "found to be making false claims and to be acting in a manner that puts people's physical, mental or psychological health, safety or welfare at risk"—and in a world first, this law applies to conversion therapy for adults as well as for minors.[66][67] Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory announced in September 2017 that they are investigating similar laws.[68] Advocates for a ban on conversion therapy argued that reviews need to go beyond the practices of health professionals and into activities of religious groups[69] and the unregulated (non-medical) counselling sector.[68]

A Fairfax Media investigation in 2018 reported that "across Australia, organisations who believe that LGBTI people can or should change are hard at work. Conversion practices are hidden in evangelical churches and ministries, taking the form of exorcisms, prayer groups or counselling disguised as pastoral care. They're also present in some religious schools or practised in the private offices of health professionals. They're pushed out through a thriving network of courses and mentors in the borderless world of cyberspace, cloaked in the terminology of 'self improvement' or 'spiritual healing.'"[70] A study of Pentecostal-Charismatic Churches found that LGBTI parishioners were faced with four options: remain closeted, come out but commit to remaining celibate, undergo conversion therapy, or leave the church... the majority took the last option, though typically only after "agonising attempts to reconcile their faith and their sexuality."[71] The study provides corroboration that conversion therapy remains practiced within religious communities.

Following the Fairfax investigation, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews called on Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull to support outlawing conversion therapy as part of the national mental health strategy. Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt declared that the issue is one for the states as no Commonwealth funding goes to sexual orientation change efforts—though "gay conversion ideology has been quietly pushed in schools as part of the federal government's chaplaincy program."[72] The report noted that the Victorian law applies only to people offering health services[70] and so does not catch religious groups and charities "who say they are helping same-sex attracted people to live in accordance with their faith."[72]

Chris Csabs, a survivor of conversion therapy and LGBT+ advocate, joined Andrews in calling for the Federal Government to outlaw conversion therapy, declaring that "praying the gay away nearly killed me."[73][74][75] He established a petition calling on Turnbull and Hunt to act to outlaw conversion therapy, declaring: "I prayed to God asking him to either heal me, or kill me. I was so depressed, I wanted to die."[74] In April 2018, Shadow Health Minister Catherine King wrote a response to the petition: "I'm writing to let you know that Labor stands with you, Chris Csabs and the medical experts in opposing gay conversion therapy...two Turnbull Government ministers—the Acting Prime Minister and the Health Minister—have now failed to condemn the practice when given the chance."[76] Shortly after Catherine King's response, Health Minister for Queensland Dr Steven Miles voiced his concerns over the practise and stated that the Federal Health Minister should be working with the states to enact change.[77]

In May 2018, the Victorian Health Minister Jill Hennessy called for an inquiry into gay conversion therapies. In an unprecedented move, the state government indicated it would not only investigate health professionals but will focus on religious and faith-based ministries propagating Gay Conversion ideologies.[78][79] The following day, Health Minister for the Australian Capital Territory Meegan Fitzharris followed Catherine King's lead by also responding to the petition, stating that, "The ACT government will ban gay conversion therapy. It is abhorrent and completely inconsistent with the inclusive values of Canberrans."[80]

In September 2018, SOCE (Sexual orientation Change Efforts) Survivor Statement, a document written by a coalition of survivors of conversion practices calling on the Australian Government to intervene to stop conversion practices occurring, was sent with the petition to key members of parliament.[81] The authors of the SOCE Survivor Statement, which became known as The SOGICE (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Conversion Efforts) Survivor Statement in 2019, coined new terms such as 'LGBTQA+ conversion practices', 'conversion movement' and 'conversion ideology' to more accurately reflect their experiences. The SOGICE Survivors Statement lists survivor-led recommendations to the Australian government in order to stop conversion practices in Australia.[82][83][84]

United States[]

20th century[]

Psychoanalysis started to receive recognition in the United States in 1909, when Sigmund Freud delivered a series of lectures at Clark University in Massachusetts at the invitation of G. Stanley Hall.[85] In 1913, Abraham Brill wrote "The Conception of Homosexuality", which he published in the Journal of the American Medical Association and read before the American Medical Association's annual meeting. Brill criticised physical treatments for homosexuality such as bladder washing, rectal massage, and castration, along with hypnosis, but referred approvingly to Freud and Sadger's use of psychoanalysis, calling its results "very gratifying".[86] Since Brill understood curing homosexuality as restoring heterosexual potency, he claimed that he had cured his patients in several cases, even though many remained homosexual.[29][87]

Wilhelm Stekel, an Austrian, published his views on treatment of homosexuality, which he considered a disease, in the American Psychoanalytic Review in 1930. Stekel believed that "success was fairly certain" in changing homosexuality through psychoanalysis provided that it was performed correctly and the patient wanted to be treated. In 1932, The Psychoanalytic Quarterly published a translation of Helene Deutsch's paper "On Female Homosexuality". Deutsch reported her analysis of a lesbian, who did not become heterosexual as a result of treatment, but who managed to achieve a "positive libidinal relationship" with another woman. Deutsch indicated that she would have considered heterosexuality a better outcome.[87]

Edmund Bergler was the most important psychoanalytic theorist of homosexuality in the 1950s.[29] He was vociferous in his opposition to Alfred Kinsey. Kinsey's work, and its reception, led Bergler to develop his own theories for treatment, which were essentially to "blame the victim", in the evaluation of Jennifer Terry, associate professor of Woman's Studies.[88] Bergler claimed that if gay people wanted to change, and the right therapeutic approach was taken, then they could be cured in 90% of cases.[89] Bergler used confrontational therapy in which gay people were punished in order to make them aware of their masochism. Bergler openly violated professional ethics to achieve this, breaking patient confidentiality in discussing the cases of patients with other patients, bullying them, calling them liars and telling them they were worthless.[88] He insisted that gay people could be cured. Bergler confronted Kinsey because Kinsey thwarted the possibility of cure by presenting homosexuality as an acceptable way of life, which was the basis of the gay rights activism of the time.[88] Bergler popularised his views in the United States in the 1950s using magazine articles and books aimed at non-specialists.[88][90]

In 1951, the mother who wrote to Freud asking him to treat her son sent Freud's response to the American Journal of Psychiatry, in which it was published.[29] The 1952 first edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) classified homosexuality as a mental disorder.[91]

During the three decades between Freud's death in 1939 and the Stonewall riots in 1969, conversion therapy received approval from most of the psychiatric establishment in the United States.[92] In 1962, Irving Bieber et al. published , in which they concluded that "although this change may be more easily accomplished by some than by others, in our judgment a heterosexual shift is a possibility for all homosexuals who are strongly motivated to change".[93]

There was a riot in 1969 at the Stonewall Bar in New York after a police raid. The Stonewall riot acquired symbolic significance for the gay rights movement and came to be seen as the opening of a new phase in the struggle for gay liberation. Following these events, conversion therapy came under increasing attack. Activism against conversion therapy increasingly focused on the DSM's designation of homosexuality as a psychopathology.[91] In 1973, after years of criticism from gay activists and bitter dispute among psychiatrists, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality as a mental disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Supporters of the change used evidence from researchers such as Kinsey and Evelyn Hooker. Psychiatrist Robert Spitzer, a member of the APA's Committee on Nomenclature, played an important role in the events that led to this decision. Critics argued that it was a result of pressure from gay activists, and demanded a referendum among voting members of the Association. The referendum was held in 1974 and the APA's decision was upheld by a 58% majority.[91]

The APA removed ego-dystonic homosexuality from the DSM-III-R in 1987 and opposes the diagnosis of either homosexuality or ego-dystonic homosexuality as any type of disorder.[94]

Joseph Nicolosi had a significant role in the development of conversion therapy as early as the 1990s, publishing his first book, Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality, in 1991.[95][96] In 1992, Nicolosi, with Charles Socarides and Benjamin Kaufman, founded the National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH), an organization that opposed the mainstream medical view of homosexuality and aimed to "make effective psychological therapy available to all homosexual men and women who seek change".[97] NARTH has operated under the name "Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity" (ATCSI) since 2014.[98]

In 1998, Christian right groups including the Family Research Council and the American Family Association spent $600,000 on advertising promoting conversion therapy.[99] John Paulk and his then wife Anne featured in full-page newspaper spreads.[100]

21st century[]

United States Surgeon General David Satcher in 2001 issued a report stating that "there is no valid scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed".[18] The same year, a study by Robert Spitzer concluded that some highly motivated individuals whose orientation is predominantly homosexual can become predominantly heterosexual with some form of reparative therapy.[101] Spitzer based his findings on structured interviews with 200 self-selected individuals (143 males, 57 females). He told The Washington Post that the study "shows some people can change from gay to straight, and we ought to acknowledge that".[102] Spitzer's study caused controversy and attracted media attention.[1] Spitzer recanted his study in 2012,[103] and apologized to the gay community for making unproven claims of the efficacy of reparative therapy,[104] calling it his only professional regret.[105]

The American Psychoanalytic Association spoke against NARTH in 2004, stating "that organization does not adhere to our policy of nondiscrimination and ... their activities are demeaning to our members who are gay and lesbian".[106] The same year, a survey of members of the American Psychological Association rated reparative therapy as "certainly discredited", though the authors warn that the results should be interpreted carefully as an initial step, not as a final deliberation.[107]

The American Psychological Association in 2007 convened a task force to evaluate its policies regarding reparative therapy.[108]

In 2008, the organizers of an APA panel on the relationship between religion and homosexuality canceled the event after gay activists objected that "conversion therapists and their supporters on the religious right use these appearances as a public relations event to try and legitimize what they do".[109][110]

In 2009, American Psychological Association stated that it "encourages mental health professionals to avoid misrepresenting the efficacy of sexual orientation change efforts by promoting or promising change in sexual orientation when providing assistance to individuals distressed by their own or others' sexual orientation and concludes that the benefits reported by participants in sexual orientation change efforts can be gained through approaches that do not attempt to change sexual orientation".[111]

The ethics guidelines of major mental health organizations in the United States vary from cautionary statements to recommendations that conversion therapy be prohibited (American Psychiatric Association) to recommendations against referring patients to those who practice it (American Counseling Association).[17][112] In a letter dated 23 February 2011 to the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, the Attorney General of the United States stated "while sexual orientation carries no visible badge, a growing scientific consensus accepts that sexual orientation is a characteristic that is immutable".[113]

Gay rights groups and other groups concerned with mental health fear that reparative therapy can increase the chances of depression and suicide. President Barack Obama expressed opposition to the practice in 2015.[114]

Theories and techniques[]

Behavioral modification[]

Before the American Psychiatric Association's 1973 decision to remove homosexuality from the DSM, practitioners of conversion therapy employed aversive conditioning techniques, involving electric shock and nausea-inducing drugs during presentation of same-sex erotic images. Cessation of the aversive stimuli was typically accompanied by the presentation of opposite-sex erotic images, with the objective of strengthening heterosexual feelings. In "Aversion therapy for sexual deviation: a critical review", published in 1966, M. P. Feldman claimed a 58% cure rate, but Douglas Haldeman is skeptical that such stressful methods permit feelings of sexual responsiveness, and notes that Feldman defined success as suppression of homosexuality and increased capacity for heterosexual behavior.[115]

Another method used was the covert sensitization method, which involves instructing patients to imagine vomiting or receiving electric shocks, writing that only single case studies have been conducted, and that their results cannot be generalized. Haldeman writes that behavioral conditioning studies tend to decrease homosexual feelings, but do not increase heterosexual feelings, citing Rangaswami's "Difficulties in arousing and increasing heterosexual responsiveness in a homosexual: A case report", published in 1982, as typical in this respect.[116]

Haldeman concludes that such methods can be called torture, besides being ineffective. He writes that "Individuals undergoing such treatments do not emerge heterosexually inclined; rather they become shamed, conflicted, and fearful about their homosexual feelings."[117]

Ex-gay ministry[]

Some sources describe ex-gay ministries as a form of conversion therapy, while others state that ex-gay organizations and conversion therapy are distinct methods of attempting to convert gay people to heterosexuality.[1][12][118][119] Ex-gay ministries have also been called transformational ministries.[12] Some state that they do not conduct clinical treatment of any kind.[120] Exodus International once believed reparative therapy could be a beneficial tool.[120] The umbrella organization in the United States ceased activities in June 2013, and the three member board issued a statement which repudiated its aims and apologized for the harm their pursuit has caused to LGBT people.[121]

Psychoanalysis[]

Haldeman writes that psychoanalytic treatment of homosexuality is exemplified by the work of Irving Bieber et al. in Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals. They advocated long-term therapy aimed at resolving the unconscious childhood conflicts that they considered responsible for homosexuality. Haldeman notes that Bieber's methodology has been criticized because it relied upon a clinical sample, the description of the outcomes was based upon subjective therapist impression, and follow-up data were poorly presented. Bieber reported a 27% success rate from long-term therapy, but only 18% of the patients in whom Bieber considered the treatment successful had been exclusively homosexual to begin with, while 50% had been bisexual. In Haldeman's view, this makes even Bieber's unimpressive claims of success misleading.[122]

Haldeman discusses other psychoanalytic studies of attempts to change homosexuality. Curran and Parr's "Homosexuality: An analysis of 100 male cases", published in 1957, reported no significant increase in heterosexual behavior. Mayerson and Lief's "Psychotherapy of homosexuals: A follow-up study of nineteen cases", published in 1965, reported that half of its 19 subjects were exclusively heterosexual in behavior four and a half years after treatment, but its outcomes were based on patient self-report and had no external validation. In Haldeman's view, those participants in the study who reported change were bisexual at the outset, and its authors wrongly interpreted capacity for heterosexual sex as change of sexual orientation.[123]

Reparative therapy[]

The term "reparative therapy" has been used as a synonym for conversion therapy generally, but according to Jack Drescher it properly refers to a specific kind of therapy associated with the psychologists Elizabeth Moberly and Joseph Nicolosi.[23] The term reparative refers to Nicolosi's postulate that same-sex attraction is a person's unconscious attempt to "self-repair" feelings of inferiority.[124][125][126]

Most mental health professionals and the American Psychological Association consider reparative therapy discredited, but it is still practiced by some.[4] In 2014 the Republican Party of Texas endorsed "counseling, which offers reparative therapy and treatment" in their party platform.[127] Exodus International regarded reparative therapy as a useful tool to eliminate "unwanted same-sex attraction"[120] but ceased activities in June 2013 and issued a statement repudiating its aims and apologizing for the harm the organization had caused to LGBT people.[121] Psychoanalysts critical of Nicolosi's theories have offered gay-affirmative approaches as an alternative to reparative therapy.[23][128]

Sex therapy[]

Haldeman has described William Masters' and Virginia Johnson's work on sexual orientation change as a form of conversion therapy.[129]

In Homosexuality in Perspective, published in 1979, Masters and Johnson viewed homosexuality as the result of blocks that prevented the learning that facilitated heterosexual responsiveness, and described a study of 54 gay men who were dissatisfied with their sexual orientation. The original study did not describe the treatment methodology used, but this was published five years later. John C. Gonsiorek criticized their study on several grounds in 1981, pointing out that while Masters and Johnson stated that their patients were screened for major psychopathology or severe neurosis, they did not explain how this screening was performed, or how the motivation of the patients to change was assessed. Nineteen of their subjects were described as uncooperative during therapy and refused to participate in a follow-up assessment, but all of them were assumed without justification to have successfully changed.[130]

Haldeman writes that Masters and Johnson's study was founded on heterosexist bias, and that it would be tremendously difficult to replicate. In his view, the distinction Masters and Johnson made between "conversion" (helping gay men with no previous heterosexual experience to learn heterosexual sex) and "reversion" (directing men with some previous heterosexual experience back to heterosexuality) was not well founded. Many of the subjects Masters and Johnson labelled homosexual may not have been homosexual, since, of their participants, only 17% identified themselves as exclusively homosexual, while 83% were in the predominantly heterosexual to bisexual range. Haldeman observed that since 30% of the sample was lost to the follow-up, it is possible that the outcome sample did not include any people attracted mainly or exclusively to the same sex. Haldeman concludes that it is likely that, rather than converting or reverting gay people to heterosexuality, Masters and Johnson only strengthened heterosexual responsiveness in people who were already bisexual.[131]

Lobotomy[]

In the 1940s and 1950s, U.S. neurologist Walter Freeman popularized the ice-pick lobotomy as a treatment for homosexuality. He personally performed as many as 3,439[132] lobotomy surgeries in 23 states, of which 2,500 used his ice-pick procedure,[133] despite the fact that he had no formal surgical training.[134] Up to 40% of Freeman's patients were gay individuals subjected to a lobotomy[135] in order to change their homosexual orientation, leaving most of these individuals severely disabled for the rest of their lives.[136] While promoted at the time as a treatment for various psychoses, the effectiveness of lobotomy in changing sexual orientation was already the subject of critical research in 1948 when a single case was investigated by Joseph Friedlander and Ralph Banay.[137] A video depicting the "ice-pick lobotomy" of a homosexual man was featured in the documentary film, Changing Our Minds: The Story of Dr. Evelyn Hooker.[4][24][25]

Studies of conversion therapy[]

Penile-phallometric assessment studies[]

Sexologist Kurt Freund used penile plethysmographs which measure bloodflow to the penis to test men's claims of sexual reorientation from homosexual to heterosexual. In a study published in 1960, he found no support for the claim that the homosexual men had become heterosexual – they were still aroused by imagery of men.[138] In 1976 Conrad and Wincze found that physiological arousal measurements did not support the positive reports of men who had participated in conversion therapy – they too were still aroused by imagery of men.[138]

In a prominent 2016 review of the scientific literature on sexual orientation, J. Michael Bailey and six other scientists critique claims of sexual reorientation therapy because they rely on self-reports, not scientific tests of automatic responses to erotic stimuli or other men/women. They say that along with tests of penile blood flow, claims of sexual reorientation could also be tested by measuring relative viewing time of pictures of attractive men versus attractive women, but this is complicated by the possibility that "conversion therapy might encourage the individual to avoid looking at same-sex targets and to look more at other-sex targets. If effective, this would change viewing-time patterns but not necessarily sexual orientation".[138] In 2017, psychologist Warren Throckmorton said that Joseph Nicolosi, a prominent practitioner of conversion therapy, had previously been offered the chance to assess the viability of his therapy by J. Michael Bailey. Bailey informed Nicolosi that he could bring his patients to his lab at Northwestern University to test their automatic responses to erotic cues and images of men and women with brain scanning technology. Throckmorton wrote that "Nicolosi never took him up on the offer" and that Bailey confirmed the offer was still open.[139]

Medical treatments[]

Attempts to change sexual orientation of gay adults in medical literature have failed. These attempts usually included various forms of behavioral and aversive therapy, often involving showing erotic or pornographic imagery to homosexuals while they swallowed an emetic drug to induce vomiting. Other medical approaches attempted to "cure" homosexuality through castration (removal of testes), injection of various hormones, electroconvulsive shocks, and lobotomy (a surgical removal of the frontal lobe of the brain). American historian Jonathan Katz counted 36 methods used during the 1900s in North America which attempted to cure homosexuality. No reproducible results could ever be achieved.[140]

"Can Some Gay Men and Lesbians Change Their Sexual Orientation?"[]

In October 2003, Robert Spitzer presented "Can Some Gay Men and Lesbians Change Their Sexual Orientation? 200 Participants Reporting a Change from Homosexual to Heterosexual Orientation", a study of attempts to change homosexual orientation through ex-gay ministries and conversion therapy, at the American Psychiatric Association's convention in New Orleans. The study was partly a response to the APA's 2000 statement cautioning against clinical attempts at changing homosexuality, and was aimed at determining whether such attempts were ever successful rather than how likely it was that change would occur for any given individual. Spitzer wrote that some earlier studies provided evidence for the effectiveness of therapy in changing sexual orientation, but that all of them suffered from methodological problems.[1] Spitzer's study relied exclusively on self-reported sexual orientation change from his interviews with men on the phone.

In 2012, Spitzer renounced[141][142] and retracted this study, stating "I was quite wrong in the conclusions that I made from this study. The study does not provide evidence, really, that gays can change. And that's quite an admission on my part."[103][143][144][145] He also apologized to the gay community for making unproven claims of the efficacy of reparative therapy,[104] calling it his only professional regret.[105] Spitzer has requested that all "ex-gay" therapy organizations such as NARTH, PFOX, American College of Pediatricians, and Focus on the Family stop citing his study as evidence for conversion therapy.[145]

Analysis of the May 2001 Spitzer report[]

Spitzer reported that after intervention, 66% of the men and 44% of the women had achieved "Good Heterosexual Functioning", which he defined as requiring five criteria (being in a loving heterosexual relationship during the last year, overall satisfaction in emotional relationship with a partner, having heterosexual sex with the partner at least a few times a month, achieving physical satisfaction through heterosexual sex, and not thinking about having homosexual sex more than 15% of the time while having heterosexual sex). He found that the most common reasons for seeking change were lack of emotional satisfaction from gay life, conflict between same-sex feelings and behavior and religious beliefs, and desire to marry or remain married.[1][146] This paper was widely reported in the international media and taken up by politicians in the United States, Germany, and Finland, and by conversion therapists.[1]

In 2003, Spitzer published the paper in the Archives of Sexual Behavior. Spitzer's study has been criticized on numerous ethical and methodological grounds, and "press releases from both NGLTF and HRC sought to undermine Spitzer's credibility by connecting him politically to right-wing groups that had backed the ex-gay movement".[147] Gay activists argued that the study would be used by conservatives to undermine gay rights.[1] Spitzer acknowledged that the study sample consisted of people who sought treatment primarily because of their religious beliefs (93% of the sample), served in various church-related functions, and who publicly spoke in favor of changing homosexual orientation (78%), and thus were strongly motivated to overreport success. Critics felt he dismissed this source of bias, without even attempting to measure deception or self-deception (a standard practice in self-reporting psychological tests like MMPI-2).[148] That participants had to rely upon their memories of what their feelings were before treatment may have distorted the findings. It was impossible to determine whether any change that occurred was due to the treatment because it was not clear what it involved and there was no control group.[1] Spitzer's own data showed that claims of change were reflected mostly in changes in self-labelling and behavior, less in attractions, and least in the homoerotic content during the masturbatory fantasies; this particular finding was consistent with other studies in this area.[149] Participants may have been bisexual before treatment. Follow-up studies were not conducted.[1] Spitzer stressed the limitations of his study. Spitzer said that the number of gay people who could successfully become heterosexual was likely to be "pretty low",[150] and conceded that his subjects were "unusually religious".[151]

Previous research which did not rely upon self-reports, but instead used penile plethysmographs to measure bloodflow to the penis (a measure of sexual arousal), has not supported male patients claims of sexual reorientation from homosexual to heterosexual.[138]

"Changing Sexual Orientation: A Consumer's Report"[]

Ariel Shidlo and Michael Schroeder found in "Changing Sexual Orientation: A Consumer's Report", a peer-reviewed study of 202 respondents[152] published in 2002, that 88% of participants failed to achieve a sustained change in their sexual behavior and 3% reported changing their orientation to heterosexual. The remainder reported either losing all sexual drive or attempting to remain celibate, with no change in attraction. Some of the participants who failed felt a sense of shame and had gone through conversion therapy programs for many years. Others who failed believed that therapy was worthwhile and valuable. Many respondents felt harmed by the attempt to change, and reported depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, hypervigilance of gender-deviant mannerisms, social isolation, fear of being a child abuser and poor self-esteem. Of the 8 respondents (out of a sample of 202) who reported a change in sexual orientation, 7 worked as ex-gay counselors or group leaders.[153]

Other[]

A report by Cornell University looked at 47 peer-reviewed studies and concluded "that there is no credible evidence that sexual orientation can be changed through therapeutic intervention."[154]

Medical, scientific and legal views[]

Legal status[]

| Country | Details |

|---|---|

| De facto ban: Albania's national psychological association banned its members from practising conversion therapy in 2020.[155] | |

| Nationwide ban: Since 2010, no diagnosis can be made in the field of mental health on the exclusive basis of "sexual choice or identity".[156] The ban only applies to registered health professionals. | |

| Banned in two states and the Capital Territory: Conversion therapy has been a criminal offence in Queensland since August 2020. Banned in Victoria since February 2021.[157] Bans have been proposed in Western Australia. The ACT law banning conversion therapy went into effect on 4 March 2021.[158]

On 9 February 2016, the Government of Victoria introduced a legislative bill to the lower house of the Victorian Parliament. The bill created a Health Complaints Commissioner with powers to conduct investigations and inquiries into conversion therapy.[65] It passed the lower house on 25 February 2016, passed the upper house on 14 April 2016 with minor amendments and passed the lower house with the attached amendments on 27 April 2016. Royal assent was granted on 5 May 2016. The law, known as the Health Complaints Act 2016,[159] went into effect on 1 February 2017. On 17 May 2018, Health Complaints Commissioner opened an inquiry into conversion therapy,[160] which concluded on 1 February 2019 and which recommended a full ban and support for survivors.[161] On 3 February 2019 the Government of Victoria announced plans to ban conversion therapy. The Bill was passed in February 2021. In April 2018, Health Minister Greg Hunt confirmed that the Australian Government does not support conversion therapy.[162] On 13 August 2020, the state of Queensland became the first state in Australia to criminalise conversion therapy. Under state law, health professionals could face an 18-month jail term for attempting to change or suppress a person's sexual orientation or gender identity using practices such as aversion therapy, hypnotherapy, and psychoanalysis.[163] The state government of Western Australia intend to review whether further legislation is needed.[68] | |

| Nationwide ban: In 1999, the Federal Council of Psychology issued two provisions which state that "psychologists shall not collaborate in events or services offering treatment and cure for homosexuality", and that "psychologists will neither pronounce nor participate in public speeches, in the mass media, reinforcing social prejudice related to homosexuals as pursuing any kind of psychological disorder".[164] Brazil thus became the first country in the world to ban conversion therapy.[165] In 2013, the Commission for Human Rights of Brazil's lower house of Congress, headed by an evangelical Christian man, approved legislation that would nullify the council's provisions and legalize conversion therapy.[165] The bill subsequently died without any more legislative action. In September 2017, a federal judge in Brasília approved the use of conversion therapy by a psychologist to "cure" people of homosexuality, overruling the 1999 decision.[166] However, in December 2017, the same judge changed his decision, keeping the "treatment" banned.[167] In January 2018, the Federal Psychology Council established norms of performance for psychologists in relation to transsexual and transvestite people, also banning any conversion therapy.[168] | |

|

Banned in six provinces and territories and various municipalities: Conversion therapy is banned in the province of Manitoba (since 2015),[169][170] for minors in Ontario (since 2015),[171] for minors (though allowed for "mature minors" between the ages of 16 and 18 if they consent) in Nova Scotia (since 2018),[172][173] for minors in Prince Edward Island (since 2020),[174] in Quebec (since 2020),[175] the territory of Yukon (since 2020),[176] and numerous municipalities including Vancouver (since 2018),[177] Edmonton (since 2019),[178] and Calgary (since 2020).[179] On September 23, 2020. Bill C-6 was introduced by the government in the House of Commons, it would have prohibited performing conversion therapy on a child, forcing someone to undergo conversion therapy against their will, advertising or materially benefiting from conversion therapy, and removing a child from Canada to perform conversion therapy.[180] On 22 June 2021, it passed the lower house (263 to 63), and was sent to the Senate.[181] However the Senate failed to pass the bill after some Senators objected to the government's request to recall the chamber from its summer recess, so that the bill may have been considered before Parliament was dissolved for an expected snap election.[182] The election was called on August 15 and the bill died on the order paper.[183] On November 29, the-elected government introduced a new version of the bill for the 44th Parliament, which broadened the ban's coverage to include adults, and identified it as one of its priority bills it hoped to pass before the end of the year.[184] The bill passed the House of Commons on December 1 without a recorded vote after all parties unanimously agreed to expedite it, and likewise passed the Senate on December 7.[185][186] The bill received royal assent on 8 December, 2021, and will come into effect on 7 January, 2022.[187] | |

| Nationwide ban: Law 21.331 on the Recognition and Protection of the Rights of People in Mental Health Care, enacted on April 23, 2021, states in its article 7: "The diagnosis of the state of mental health must be established as dictated by the clinical technique, considering biopsychosocial variables. It cannot be based on criteria related to the political, socioeconomic, cultural, racial or religious group of the person, nor to the identity or sexual orientation of the person, among others."[188][189]

In February 2016, the Chilean Ministry of Health expressed their opposition to conversion therapy. The statement said: "We consider that practices known as conversion therapies represent a grave threat to health and well-being, including the life, of the people who are affected."[190] | |

| Case-by-case ban: In China, courts have ruled instances of conversion therapy to be illegal on two occasions; however, legal precedents in China are not enforceable in future cases. In December 2014, a Beijing court ruled in favor of a gay man in a case against a conversion therapy clinic. The court ruled that such treatments are illegal and ordered the clinic to apologize and pay monetary compensation.[191] In June 2016, a man from Henan Province sued a hospital in the city of Zhumadian for forcing him to undergo conversion therapy,[192] and was also awarded a public apology and compensation.[193] Following these two successful rulings, LGBT groups are now calling on the Chinese Health Ministry to ban conversion therapy.[194] However, as of April 2019, no measure has been taken by the government to ban conversion therapy, and such treatments are still in fact being actively promoted throughout the country.[195] | |

| Nationwide ban: In Ecuador, the Government's view is that conversion therapy is proscribed by a 1999 law banning anti-gay discrimination.[196] In addition, Article 151 of the 2014 Penal Code prohibits conversion therapy, equating it to torture, and provides 10 years' imprisonment for those practicing it.[197]

In January 2012, the Ecuadorian Government raided three conversion therapy clinics in Quito, rescued dozens of women who were abused and tortured in an effort to "cure their homosexuality", and promised to shut down every such clinic in the country.[198] | |

| Nationwide ban: The Mental Health Decree 2010 states that people are not to be considered mentally ill if they refuse or fail to express a particular sexual orientation, and prohibits any conversion therapy in the field of mental health.[199] The ban only applies to registered health professionals. | |

| Nationwide ban: In 2008, the German Government declared itself completely opposed to conversion therapy.[200]

In February 2019, German Health Minister Jens Spahn said he will seek to ban conversion therapies that claim to change sexual orientation.[201] The government banned conversion therapy for all minors in December 2019. Adult conversion therapy is only deemed illegal if consent was given due to "lack of will power" such as deceit or coercion. Psychotherapeutic and pastoral care "purposefully trying to influence one's sexual orientation" was also banned. The ban also applies to legal guardians "grossly violating their duty of care".[202] On 7 May 2020, German parliament Bundestag banned nationwide conversion therapy for minors until 18 years and forbids advertising of conversion therapy. It also forbids conversion therapy for adults, if they are decided by force, fraud or pressure.[53][203] | |

| Nationwide ban: In February 2014, the Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS) issued a statement, in which it stated that there is no evidence to prove that homosexuality is unnatural: "Based on existing scientific evidence and good practise guidelines from the field of psychiatry, the Indian Psychiatric Society would like to state that there is no evidence to substantiate the belief that homosexuality is a mental illness or a disease."[204][205]

On 7 June 2021, in delivering the verdict for the case S Sushma v. Commissioner of Police, Madras High Court Justice N Anand Venkatesh prohibited Conversion therapy.[206][207] | |

| As of May 2018, the Prohibition of Conversion Therapies Bill 2018 had passed second reading in the Seanad Éireann (Irish Senate), and was awaiting a third reading in that chamber, and passage in the Dáil Éireann.[208] However, the Bill never progressed to third reading in the Seanad, and then lapsed on 14 January 2020 due to the dissolution of the Dáil and Seanad for the 2020 Irish general election.[209] | |

| In October 2014, the Ministry of Health issued a statement announcing that it considers conversion therapy to "create false impressions of scientific recognition even though there is no scientific evidence that it is at all successful. It may also cause harm to the individual."[210]

In February 2016 and in March 2017, the Knesset rejected bills introduced by former Health Minister Yael German that would have banned conversion therapy in Israel for minors. The bills were rejected 37–45 and 26–38, respectively.[211] These efforts were blocked by Orthodox Jewish parties.[212] In 2019, the Israel Medical Association decided to expel members who continue to practice conversion therapy.[213][212] However, as of 2020 conversion therapy continues to be widely offered by religious organizations such as Atzat Nefesh under the euphemism "therapy for reversed inclinations".[212] In July 2020, a bill against conversion therapy passed the initial reading.[214] | |

| In 2013, the Lebanese Psychiatric Society stated that conversion therapy seeking to "convert" gays and bisexuals into straights has no scientific backing and asked health professionals to rely only on science when giving opinion and treatment in this matter.[215] | |

| Legal and state-backed: In February 2017, the Malaysian Government endorsed conversion therapy, claiming homosexuality can be "cured" through extensive training.[216] In June 2017, the Health Ministry began a film competition to find the best way to "cure" and prevent homosexuality. The competition was later cancelled, following massive outrage.[217] | |

| Nationwide ban: In December 2016, the Parliament of Malta unanimously approved the Affirmation of Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Gender Expression Act, becoming the first country in the European Union to ban conversion therapy.[218][219] | |

| Nationwide ban: The Mentally-Disordered Persons (Amendment) Act 2016 states that people are not to be considered mentally disordered if they express or exhibit or refuse or fail to express a particular sexual preference or sexual orientation.[220] The ban only applies to registered health professionals. | |

| Organizations offering conversion therapy in the Netherlands are not eligible for subsidies.[221] In addition, since June 2012, conversion therapies have been blocked from coverage by healthcare insurance.[222] | |

| In August 2018, Justice Minister Andrew Little announced that a conversion therapy ban could be considered as part of a reform to the Human Rights Act 1993.[223] After this plan was voted down by coalition partners New Zealand First, the Labour Party announced in October 2020 it would definitively ban the practise if re-elected.[224]

In late July 2021, Justice Minister Kris Faafoi announced a proposed law banning conversion therapy.[225][226] Youth MP and activist, Shaneel Lal has led the movement to end conversion therapy in New Zealand.[227] | |

| In 2000, the Norwegian Psychiatric Association overwhelmingly voted for the position statement that "homosexuality is no disorder or illness, and can therefore not be subject to treatment. A 'treatment' with the only aim of changing sexual orientation from homosexual to heterosexual must be regarded as ethical malpractice, and should have no place in the health system".[228] | |

| Nationwide ban: The Mental Health Act 2007 states that people are not to be considered mentally ill if they refuse or fail to express a particular sexual orientation, and prohibits any conversion therapy in the field of mental health.[229] The ban only applies to registered health professionals. | |

| The South African Society of Psychiatrists states that "there is no scientific evidence that reparative or conversion therapy is effective in changing a person's sexual orientation. There is, however, evidence that this type of therapy can be destructive".[230]

In February 2015, owners of a conversion therapy camp were found guilty of murder, child abuse and assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm after three teens were found dead at the camp. The teens were beaten with spades and rubber pipes, chained to their beds, not allowed to use the toilet at any time and forced to eat soap and their own feces, all with the aim of "curing" their homosexuality.[231] | |

| Banned in five autonomies: Conversion therapy has been banned in the autonomous communities of Murcia (since 2016),[232] Madrid (since 2017),[233] Valencia (since 2017),[234] Andalusia (since 2018),[235] and Aragon (since 2019).[236] The specifics vary by jurisdiction. For instance, in Murcia, the ban only applies to registered health professionals, but the Madrid ban applies to everyone including religious groups.

The Spanish Psychological Association states that there is no evidence to support conversion therapy. "On the contrary, there is evidence that conversion therapy leads to anxiety, depression and suicide".[237] In April 2019, following an exposé of conversion therapy in Spain, the Spanish health minister Maria Luisa Carcedo said the Spanish government would consider legislating to stamp out the practice.[238] | |

| De facto ban: In Switzerland, it is unlawful for a medical professional to carry out conversion therapy. In 2016, the Swiss Federal Council wrote in response to a parliamentary interpellation that in its view, conversion therapies are "ineffective and cause significant suffering to young people subject to them", and would constitute a breach of professional duties on the part of any care professional undertaking them. As such, in the Government's view, any care professional undertaking such therapies is liable to be sanctioned by the cantonal authorities. Whether such therapies also constitute a criminal offense is to be determined by the criminal courts in the individual case, according to the Federal Council.[239]

Reports emerged in summer 2018 of a therapist claiming to be able to "cure" homosexuality through homoeopathy. He was promptly fired, and an investigation was opened with the Geneva Ministry of Health.[240] According to the Ministry, believing that homosexuality is an illness is sufficient enough to open an investigation. The Association des Médecins du Canton de Genève describes conversion therapy as a form of charlatanism. | |

| Nationwide ban: On 13 May 2016, the Health Bureau of the Taichung City Government announced that medical institutions in Taichung are prohibited from engaging in conversion therapy. According to Shader Liu, a member of Taichung's Gender Equality Committee, any group—medical, civil or religious—that practices the treatment is violating the Taiwanese Physicians Act and Psychologists Act.[241] Regulations banning conversion therapy were expected to bypass Parliament in late January 2017 and take effect in March 2017.[242][243] According to the Physicians Act, doctors who engage in prohibited treatments are subject to fines of between NT$100,000 (US$3,095) to NT$500,000 (US$15,850) and may be suspended for one month to one year.[244] However, the proposed regulations were stalled by fierce resistance from anti-LGBT groups.[245]

Instead of pushing ahead legal amendments or new regulations, on 22 February 2018, the Ministry of Health and Welfare issued a letter to all local health authorities on the matter, which effectively banned conversion 'therapy'.[246] In the letter, the Ministry states that sexual orientation conversion is not regarded as a legitimate healthcare practice and that any individual performing the so-called therapy is liable to prosecution under the or the Protection of Children and Youths Welfare and Rights Act, depending on the circumstances.[247] | |

| In 2007, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the main professional organisation of psychiatrists in the UK, issued a report stating that: "Evidence shows that LGB people are open to seeking help for mental health problems. However, they may be misunderstood by therapists who regard their homosexuality as the root cause of any presenting problem such as depression or anxiety. Unfortunately, therapists who behave in this way are likely to cause considerable distress. A small minority of therapists will even go so far as to attempt to change their client's sexual orientation. This can be deeply damaging. Although there are now a number of therapists and organisations in the USA and in the UK that claim that therapy can help homosexuals to become heterosexual, there is no evidence that such change is possible."[248]

In 2017, the Church of England announced it considers conversion therapy "fundamentally wrong" and demanded the Government ban it.[249] After reports of a Liverpool church starving individuals for three days as a means to "cure" their homosexuality, Parliament heard calls for a legislative ban.[250] Groups such as Stonewall and Humanists UK have also long called for it to be banned. On 3 July 2018, the UK Government announced it would work towards a total ban on conversion therapy across medical, non-medical, and religious settings.[251][252] However, by the time of the 2019 general election, the issue was no longer a priority for the governing Conservative Party.[253] Stonewall notes that "in the UK, all major counselling and psychotherapy bodies, as well as the NHS, have concluded that conversion therapy is dangerous and have condemned it by signing a Memorandum of Understanding".[254] On 11 May 2021 the government stated that conversion therapy was to become a banned practice throughout England and Wales after consultation. In December 2020, the Conservative Party again changed course, this time providing government funding for a conference of faith leaders calling for an end to conversion therapy.[255] The participants are from ten different religions and include nine archbishops, sixty rabbis and senior Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs.[255] In the self-governing British dependent territory the Isle of Man, an amendment to the Sexual Offences and Obscene Publications Bill that would ban gay conversion therapy has been put forward to the House of Keys.[256] | |

|

Banned in 20 states, 2 territories, and local counties/municipalities: As of March 2020, 20 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and some counties and municipalities in the United States have passed laws banning the practice of conversion therapy on minors.[257][258][259][260][261][262][263][264] It is also banned in major cities like Miami and Cincinnati. Subsequently, legal challenges against New Jersey's and California's conversion therapy bans were filed. United States District Court Judge Freda L. Wolfson rejected the claim of New Jersey parents that it violated their rights by keeping them from treating their child for same-sex attraction. In Doe v. Christie, Wolfson wrote: "Surely, the fundamental rights of parents do not include the right to choose a specific medical or mental health treatment that the state has reasonably deemed harmful or ineffective." Wolfson added, "To find otherwise would create unimaginable and unintentional consequences." On 10 February 2015, a New Jersey Superior Court judge ruled that offering conversion services on the basis of a description of homosexuality as abnormal or a mental illness is a violation of the New Jersey Consumer Fraud Act.[265] An article about the ruling on the New Jersey Law Journal web site said the decision is "believed to be the first of its kind in the U.S."[265] On 29 August 2013, in the case of Pickup v. Brown and Welch v. Brown, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld California's ban.[266] In August 2016, the Ninth Circuit again upheld the state's ban, finding that legislation prohibiting conversion therapy is not unconstitutional.[267] The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected challenges against conversion therapy bans.[268] The states of New Jersey (2013), California (2013), Oregon (2015), Illinois (2016), Vermont (2016), New Mexico (2017), Connecticut (2017), Rhode Island (2017), Nevada (2018), Washington (2018), Hawaii (2018), Delaware (2018), Maryland (2018), New Hampshire (2019), New York (2019), Massachusetts (2019),[269] Maine (2019),[270] Colorado (2019),[271] Utah (2019), and Virginia (2020) as well as the District of Columbia (2015) and Puerto Rico (2019) ban the use of conversion therapy on minors.[272] Opinion polls have found that conversion therapy bans enjoy popular support among the American population. As of 2019, no nationwide opinion poll has been carried out, though surveys in three states (Florida, New Mexico and Virginia) show support varying between 60% and 75%. According to a 2014 national poll, only 8% of Americans believed conversion therapies to be successful.[273] | |

| Nationwide ban: Adopted in 2017, the Ley de Salud Mental ("Mental Health Law") states that in no case a diagnosis can be made in the field of mental health on the exclusive basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.[274] |

Legal status by US state[]

Although no national ban exists, several US states and individual counties ban therapy attempting to change sexual orientation as shown in the map below.

Status by health organizations[]

Many health organizations around the world have denounced and criticized sexual orientation and gender identity change efforts.[9][10][275] National health organizations in the United States have announced that there has been no scientific demonstration of conversion therapy's efficacy in the last forty years.[12][276][277][278] They find that conversion therapy is ineffective, risky and can be harmful. Anecdotal claims of cures are counterbalanced by assertions of harm, and the American Psychiatric Association, for example, cautions ethical practitioners under the Hippocratic oath to do no harm and to refrain from attempts at conversion therapy.[277]

Mainstream medical bodies state that conversion therapy can be harmful because it may exploit guilt and anxiety, thereby damaging self-esteem and leading to depression and even suicide.[279] There is also concern in the mental health community that the advancement of conversion therapy can cause social harm by disseminating inaccurate views about gender identity, sexual orientation, and the ability of LGBTQ people to lead happy, healthy lives.[10]

List of health organizations critical of conversion therapy[]

Major health organizations critical of conversion therapy include:

Multi-national health organizations[]

- World Psychiatric Association[280][281]

- Pan American Health Organization regional office of the World Health Organization[282]

- [283]

US health organizations[]

- American Medical Association[284]

- American Psychiatric Association[9][10]

- American Psychological Association[9][10]

- American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy[285]

- American Counseling Association[9][10]

- National Association of Social Workers[9][10]

- American Academy of Pediatrics[286]

- American Academy of Physician Assistants[12][287]

- American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists[288]

UK health organizations[]

- National Association of School Psychologists[275]

- UK Council for Psychotherapy[275]

- British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy[275]

- British Psychological Society[275]

- British Psychoanalytic Council[275]

- Royal College of Psychiatrists[275][289]

- British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies[289]

- [289]

- [289]

- Scottish National Health Service[289]

- English National Health Service[289]

- Royal College of General Practitioners[289]

Australian health organizations[]

- Australian Medical Association[290][291]

- Austrian Society for Public Health[292]

- Australian Psychological Society[293]

- National LGBTI Health Alliance[294]

- Royal Australian College of General Practitioners operates a unit titled "Sex, sexuality, gender diversity and health" as part of its curriculum for aspiring general practitioners and for professional development, which is intended to foster the provision of "non-judgemental holistic care that is affirming and positive when disclosure occurs and based on sound knowledge of any mental or physical health risks and requirements for screening, because like many others in the Australian population, many sex, sexuality and gender diverse individuals do not want to be solely defined by their gender or sexual identity."[295]

- Dr Catherine Yelland, President of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, stated in a press release issued by the College that "[g]ay conversion therapy is unethical, harmful and not supported by medical evidence."[68][296]

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists[297][298]

Other health organizations[]

- Albanian Order of Psychologists[299]

- Brazilian Federal Council of Psychology[164]

- Canadian Psychological Association[300]

- Chilean College of Psychologists[301]

- Hong Kong Association of Doctors in Clinical Psychology

- Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists[302]

- Hong Kong Psychological Society[303]

- Indian Psychiatric Society[204][205]

- Israel Medical Association[304]

- Lebanese Psychiatric Society[215]

- Norwegian Psychiatric Association[305]

- Psychological Society of Ireland[306]

- Public Health Agency of Canada[307]

- Spanish Psychological Association[237]

- South African Society of Psychiatrists[230]

APA taskforce study[]

The American Psychological Association undertook a study of the peer-reviewed literature in the area of sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE) and found myriad issues with the procedures used in conducting the research. The taskforce did find that some participants experienced a lessening of same sex attraction and arousal, but that these instances were "rare" and "uncommon". The taskforce concluded that, "given the limited amount of methodically sound research, claims that recent SOCE is effective are not supported".[308] Two issues with SOCE claims are that conversion therapists falsely assume that homosexuality is a mental disorder and that their research focuses almost exclusively on gay men and rarely includes lesbians.[7][12][126][151][10]

Self-determination[]

The American Psychological Association's code of conduct states that "Psychologists respect the dignity and worth of all people, and the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, and self-determination", but also that "Psychologists are aware that special safeguards may be necessary to protect the rights and welfare of persons or communities whose vulnerabilities impair autonomous decision making."[309] The American Counseling Association says that "it is of primary importance to respect a client's autonomy to request a referral for a service not offered by a counselor".[112] They said that no one should be forced to attempt to change their sexual orientation against their will, including children being forced by their parents.[310]

Supporters of SOCE focus on patient self-determination when discussing whether therapy should be available. Mark Yarhouse, of Pat Robertson's Regent University, wrote that "psychologists have an ethical responsibility to allow individuals to pursue treatment aimed at curbing experiences of same-sex attraction or modifying same-sex behaviors, not only because it affirms the client's rights to dignity, autonomy, and agency, as persons presumed capable of freely choosing among treatment modalities and behavior, but also because it demonstrates regard for diversity".[311] Yarhouse and Throckmorton, of the private Christian school Grove City College, argue that the procedure should be available out of respect for a patient's values system and because they find evidence that it can be effective.[312] Haldeman similarly argues for a client's right to access to therapy if requested from a fully informed position: "For some, religious identity is so important that it is more realistic to consider changing sexual orientation than abandoning one's religion of origin ... and if there are those who seek to resolve the conflict between sexual orientation and spirituality with conversion therapy, they must not be discouraged."[19]

In response to Yarhouse's paper, Jack Drescher argued that "any putative ethical obligation to refer a patient for reparative therapy is outweighed by a stronger ethical obligation to keep patients away from mental health practitioners who engage in questionable clinical practices".[313] Chuck Bright wrote that refusing to endorse a procedure that "has been deemed unethical and potentially harmful by most medical and nearly every professional psychotherapy regulating body cannot be justifiably identified as prohibiting client self-determination".[126] Some commentators, recommending a hard stand against the practice, have found therapy inconsistent with a psychologist's ethical duties because "it is more ethical to let a client continue to struggle honestly with her or his identity than to collude, even peripherally, with a practice that is discriminatory, oppressive, and ultimately ineffective in its own stated ends".[314] They argue that clients who request it do so out of social pressure and internalized homophobia, pointing to evidence that rates of depression, anxiety, alcohol and drug abuse and suicidal feelings are roughly doubled in those who undergo therapy.[153]

Haldeman argues that, due to concern for people whose "spiritual or religious concerns" may assume priority over their sexual orientation, mental health organizations do not ban conversion therapy outright.[19]

Ethics guidelines[]

In 1998, the American Psychiatric Association issued a statement opposing any treatment which is based upon the assumption that homosexuality is a mental disorder or that a person should change their orientation, but did not have a formal position on other treatments that attempt to change a person's sexual orientation. In 2000, they augmented that statement by saying that as a general principle, a therapist should not determine the goal of treatment, but recommends that ethical practitioners refrain from attempts to change clients' sexual orientation until more research is available.[11]

The American Counseling Association has stated that they do not condone any training to educate and prepare a counselor to practice conversion therapy. Counselors who do offer training in conversion therapy must inform students that the techniques are unproven. They suggest counselors do not refer clients to a conversion therapist or to proceed cautiously once they know the counselor fully informs clients of the unproven nature of the treatment and the potential risks. However, "it is of primary importance to respect a client's autonomy to request a referral for a service not offered by a counselor". A counselor performing conversion therapy must provide complete information about the treatment, offer referrals to gay-affirmative counselors, discuss the right of clients, understand the client's request within a cultural context, and only practice within their level of expertise.[112]

NARTH stated in 2012 that refusing to offer therapy aimed at change to a client who requests it, and telling them that their only option is to claim a gay identity, could also be considered ethically unacceptable.[315] In 2012 the British Psychological Society issued a position statement opposing any treatments that are based on an assumption that non-heterosexual orientations are pathological.[316]

A 2013 article by the Committee on Adolescence of the American Academy of Pediatrics stated "Referral for 'conversion' or 'reparative therapy' is never indicated; therapy is not effective and may be harmful to LGBTQ individuals by increasing internalized stigma, distress, and depression."[317][318]