Convoy PQ 16

| Convoy PQ 16 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Arctic naval operations of the Second World War | |||||||

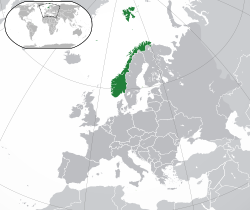

Orthographic projection of Norway (in green) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Allies | Germany | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| seven ships sunk | |||||||

Convoy PQ 16 was an Arctic convoy sent from Great Britain by the Western Allies to aid the Soviet Union during the Second World War. It sailed on 21 May 1942, reaching the Soviet northern ports on 30 May after five days of air attacks that left seven ships sunk and three damaged; 25 of the ships arrived safely.

Background[]

Arctic convoys[]

Following the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the USSR, on 22 June 1941, the UK and USSR signed an agreement in July that they would "render each other assistance and support of all kinds in the present war against Hitlerite Germany".[1] In October 1941, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, made a commitment to send a convoy to the Arctic ports of the USSR every ten days and to deliver 1,200 tanks a month from July 1942 to January 1943, followed by 2,000 tanks and another 3,600 aircraft in excess of those already promised.[1][a] The first convoy was due at Murmansk around 12 October and the next convoy was to depart Iceland on 22 October. A motley of British, Allied and neutral shipping loaded with military stores and raw materials for the Soviet war effort would be assembled at Hvalfjörður in Iceland, convenient for ships from both sides of the Atlantic.[3]

By late 1941, the convoy system used in the Atlantic had been established on the Arctic run; a convoy commodore ensured that the ships' masters and signals officers attended a briefing to make arrangements for the management of the convoy, which sailed in a formation of long rows of short columns. The commodore was usually a retired naval officer or a reservist and would be aboard one of the merchant ships (identified by a white pendant with a blue cross). The commodore was assisted by a Naval signals party of four men, who used lamps, semaphore flags and telescopes to pass signals in code.[b] In large convoys, the commodore was assisted by vice- and rear-commodores with whom he directed the speed, course and zig-zagging of the merchant ships and liaised with the escort commander.[4][c]

During the summer months, convoys went as far north as 75 N latitude then south into the Barents Sea and to the ports of Murmansk in the Kola Inlet and Archangel in the White Sea. In winter, due to the polar ice expanding southwards, the convoy route ran closer to Norway.[6]

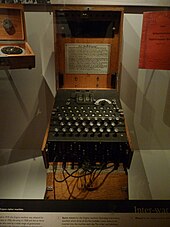

Signals intelligence[]

The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) based at Bletchley Park housed a small industry of code-breakers and traffic analysts that were intercepting and decoding German naval transmissions. By June 1941, the German Enigma machine Home Waters (Heimish) settings used by surface ships and U-boats could quickly be read. On 1 February 1942, the Enigma machines used in U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean were changed but German ships and the U-boats in Arctic waters continued with the older Heimish (Hydra from 1942, code named Dolphin by the British). By mid-1941, British Y-stations were able to read Luftwaffe wireless telegraphy (W/T) transmissions and give advance warning of Luftwaffe operations. In 1941, interception parties (code-named Headaches) were embarked on warships.[7]

From May 1942, computers sailed with the cruiser admirals in command of convoy escorts, to read Luftwaffe W/T signals which could not be intercepted by land stations in Britain. The Admiralty sent details of Luftwaffe wireless frequencies, call signs and the daily local codes to the computers. Combined with their knowledge of Luftwaffe procedures, the computers could give fairly accurate details of German reconnaissance sorties and sometimes predicted attacks twenty minutes before they were detected by radar.[7] In February 1942, the German Beobachtungsdienst B-Dienst, Observation Service) of the Kriegsmarine Marinenachrichtendienst (MND), the German Naval Intelligence Service, broke the British Naval Cypher No 3 and was able to read it until January 1943.[8]

Luftflotte 5[]

In March 1942, Adolf Hitler issued a directive for a greater anti-convoy effort to weaken the Red Army and prevent Allied troops being transferred to northern Russia, preparatory to a landing on the coast of northern Norway. Luftflotte 5 (Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff) was to be reinforced and the Kriegsmarine was ordered to put an end to Arctic convoys and naval incursions. The Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine were to work together with a simplified command structure, which was implemented after a conference; the Navy had preferred joint command but the Luftwaffe insisted on the exchange of liaison officers. Luftflotte 5 was to be reinforced by 2./Kampfgeschwader 30 (KG 30) and KG 30 was to increase its readiness for operations. A squadron of Aufklärungsflieger Gruppe 125 (Aufkl.Fl.Gr. 125) was transferred to Norway and more long range Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Kondor patrol aircraft from Kampfgeschwader 40 (KG 40) were sent from France. At the end of March the air fleet was divided, Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) [Oberst Alexander Holle], the largest command, was based at Kirkenes (2./JG 5, 10.(Z)/JG 5,[d] 1./ and 1./(F) 124) charged with attacks on Murmansk and Archangelsk as well as attacks on convoys.[9]

Part of Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) was based at Petsamo (5./JG 5, 6./JG 5 and 3./Kampfgeschwader 26 (3./KG 26), Banak (2./KG 30, 3./KG 30 and 1./(F) 22) and Billefjord (1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 125). Fliegerführer Lofoten (Oberst Hans Roth) was based at Bardufoss but had no permanently attached units, which were added according to events. At the start of the anti-shipping campaign only the coastal patrol squadrons 3./KüFlGr 125 at Trondheim and 1./Küstenfliegergruppe (1./K��.Fl.Gr. 123) at Tromsø were attached to Fliegerführer Lofoten. Fliegerführer Nord (West) was based at Sola and was responsible for the early detection of convoys and attacks south of a line from Trondheim westwards to Shetland and Iceland, with 1./(F) 22, the Kondors of 1./KG 40, short-range coastal reconnaissance squadrons 1./Küstenfliegergruppe 406 (1./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406) and 2./ Küstenfliegergruppe (2./Kü.Fl.Gr. 406) and a weather reconnaissance squadron.[10]

Prelude[]

Luftwaffe tactics[]

As soon as information was received about the assembly of a convoy, Fliegerführer Nord (West) would sent long-range reconnaissance aircraft to search Iceland and northern Scotland. Once a convoy was spotted aircraft were to keeep contact as far was as possible in the extreme weather of the area. If contact was lost its course at the last sighting would be extrapolated and overlapping sorties would be flown to regain contact. All three Fliegerführer were to co-operate as the convoy moved through their operational areas. Fliegerführer Lofoten would begin the anti-convoy operation east to a line from the North Cape to Spitzergen Island, whence Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) would take over using his and Fliegerführer Lofoten's aircraft, which would to Kirkenes or Petsamo to stay in range. Fliegerführer Nord (Ost) was not allowed to divert aircraft to ground support during the operation. Aas soon as the convoy came into range, the aircraft were to keep up a continous attack until the convoy docked at Murmansk or Archangelsk. From late March to late May the air effort against PQ 13, 14, 15 and QP 9, 10 and 11 had little effect, twelve sinkings out of 16 lost in QP convoys and two out of five sinkings from QP convoys being credited to the Luftwaffe; 166 merchant ships had sailed for Russia and 145 had survived the journey.[11]

Bad weather had been nearly as dangerous as the Luftwaffe, forcing 16 of the ships in PQ 14 to turn back. In April, the spring thaw grounded many Luftwaffe aircraft and in May bad weather led to contact being lost and convoys scattering, being impossible to find in the long Arctic night. When air attacks on convoys had taken place, the formations rarely amounted to more than twelve aircraft, greatly simplifying the task of convoy anti-aircraft gunners, who shot down several aircraft in April and May. Failings in liaison between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine were uncovered and tactical co-operation greatly enhanced, Hermann Böhm (Kommandierender Admiral Norwegen) noting that in the operation against PQ 15 and QP 11, there were no problems in co-operation between aircraft, submarines and destroyers.[12] From 152 aircraft in January, reinforcements to Luftflotte 5 increased its strength to 221 front-line aircraft by March 1942.[10] By May Luftflotte 5 had 264 aircraft based around the North Cape in nothern Norway, consisting of 108 Ju 88 long-range bombers, 42 Heinkel 111 torpedo-bombers, 15 Heinkel He 115 float-plane torpedo-bombers, 30 Junkers Ju 87 dive-bombers and 74 long range Focke Wulf 200s, Junkers 88s and Blohm & Voss BV 138s.[13]

German air–sea rescue[]

The Luftwaffe sea rescue service (Seenotdienst) along with the Kriegsmarine, the Norwegian Norwegian Society for Sea Rescue (RS) and ships on passage recovered aircrew and shipwrecked sailors from the water. The service comprised Seenotbereich VIII at Stavanger covering Stavanger, Bergen and Trondheim and Seenotbereich IX at Kirkenes for Tromsø, Billefjord and Kirkenes. Co-operation was as important in rescues as it was in anti-shipping operations, if people were to be saved before they succumbed to the climate and severe weather. The sea rescue aircraft comprised Heinkel He 59 floatplanes and Dornier Do 18 and Dornier Do 24 seaplanes. Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL, the high command of the Luftwaffe) was not able to increase the number of search and rescue aircraft in Norway, due to a general shortage of aircraft and crews, despite Stumpff pointing out that coming down in such cold waters required extremely swift recovery and that his crews "must be given a chance of rescue" or morale could not be maintained. After the experience of PQ 16, Stumpff gave the task to the coastal reconnaissance squadrons, whose aircraft were not usually engaged in attacks on convoys. They would henceforth stand by to rescue aircrew during anti-shipping operations.[14]

Cruiser and distant escorts[]

After a naval action on 2 May, the Admiralty judged that the threat from German destroyers had declined and that cruisers need not escort PQ 16 beyond Bear Island. HMS Nigeria (Admiral Harold Burrough, commander cruiser covering force) and its destroyers HMS Oribi, Onslow and Marne departed from Seidisfiord on 23 May with the escorting destroyers for PQ 16, Garland (Polish), Volunteer, Achates, Ashanti and Martin. The heavy cruisers HMS Kent, Norfolk and the light cruiser Liverpool arrived later from Hvalfjörður on the west coast of Iceland. The Admiralty anticipated that the main threat to PQ 16/QP 12 were the cruiser Admiral Scheer, which was at Narvik by 10 May and the heavy cruiser Lützow which arrived on 26 May, the oiler (Troßschiff) Dithmarschen, the destroyer Hans Lody and the torpedo boat T7. To guard against a sortie by the battleship Tirpitz the aircraft carrier Victorious, the battleships HMS Duke of York (Admiral John Tovey, commander distant covering force) and USS Washington, the heavy cruisers USS Wichita and HMS London with nine British and four US fleet destroyers were to patrol to the north-east of Iceland. Five British and three Soviet submarines were to patrol off Norway and the Russians promised to attack Luftwaffe airfields in northern Norway with 200 bombers of the Soviet Air Forces (Voyenno-Vozdushnyye Sily, VVS). (The Russians could only provide 20 bombers for an attack after the main German operation against the convoy had ended.)[15]

Convoy escorts[]

Russia-bound[]

The 36 ships of PQ 16, the largest Arctic convoy yet, sailed from Hvalfjörður in Iceland on 21 May 1942; the departure was reported by a German spy in Reykjavik. The convoy formed nine columns with a close escort of the minesweeper and the naval trawlers St Elstan, Lady Madeleine, Northern Spray and the Free French Retriever, which had to return after three days, being too slow to keep up. The merchant ship SS Empire Lawrence a catapult aircraft merchant ship that carried a Hawker Hurricane fighter for air defence. On 23 May, , an auxiliary anti-aircraft cruiser, joined the convoy from Seyðisfjörður (Seidisfiord). A converted steamer, Alynbank was equipped with radar, four pairs of high-angle 4-inch guns with director control, two quadruple QF 2-pounder Mark VIII "pom-pom" guns and 20 mm Oerlikon guns with a Royal Navy crew and acting-captain Henry Nash in comamnd.[16] Alynbank was accompanied by the corvettes Honeysuckle, Starwort, the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) Hyderabad and the Free French Roselys.[17] The T-class submarine HMS Trident and the S-class submarine Seawolf joined the convoy, as did Force Q, the fleet oiler RFA Black Ranger and the Hunt class destroyer HMS Ledbury.[16]

QP 12[]

The returning ships of QP 12 departed from Kola Inlet on the same day, guided out to sea by four British minesweepers. The convoy was led by the destroyer HMS Inglefield with the destroyers HMS Escapade, Venomous, Badsworth and the Norwegian HNoMS St. Albans, the trawlers Cape Palliser, Northern Pride, Northern Wave and Vizalma, the auxiliary anti-aircraft cruiser HMS Ulster Queen and the CAM ship SS Empire Morn; two Russian destroyers accompanied the convoy as far as longitude 30° East.[16]

Convoys PQ 16–QP 12[]

At this time of the year, the convoy would be operating during the Arctic summer in the midnight sun; perpetual daylight lessened the effectiveness of U-boat attacks but made round-the-clock air attacks more likely. It also increased the chance of early detection by German reconnaissance aircraft.[18]

On 25 May, PQ 16 met its cruiser escort but at 6:00 a.m.was spotted by a Focke-Wulf Fw 200 reconnaissance aircraft, which commenced shadowing. That evening the Luftwaffe began attacks which continued for the next five days, when[clarification needed] the convoy came within range of Soviet fighter cover. One ship was damaged and forced to return under escort. On 26 May all air attacks were repulsed but Syros was torpedoed by the submarine U-703. By 27 May the air attacks began to break through; three ships were sunk and another damaged around noon; another sunk and one damaged in mid-afternoon. That evening two more ships were sunk and another damaged. On 28 May, the convoy was joined by the Eastern Local escort, of three Soviet destroyers and four minesweepers. The extra fire-power of the Soviet ships defeated the remaining air attacks.[19]

At the entrance to the White Sea the convoy encountered ice and two icebreakers were required to clear the passage. On 29 May the convoy divided, six ships continuing on to Archangel, while the remainder docked at Murmansk.[19] Of the 125,000 long tons (127,000 t) of cargo that PQ 16 started with 32,400 long tons (32,900 t) were lost. This included 147 of the 468 tanks embarked, 77 of 201 aircraft, and 770 out of 3,277 vehicles.[13] Eight merchant ships had been sunk, six by air attack, one by U-703 and one had struck a mine. Two U-boats had been damaged by the escorts and the convoy QP 12, on the reciprocal journey claimed the certain destruction of a Junkers Ju 88 by Pilot Officer Hay (Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve) from the CAM ship Empire Morn's Hawker Sea Hurricane, who was killed while parachuting. Four more were shot down by anti-aircraft fire, with 16 aircraft claimed as probably destroyed.[19]

Aftermath[]

Analysis[]

When Convoy PQ 16 was assembled off Iceland Churchill declared it would be worthwhile if even 50 per cent[clarification needed] arrived at Russian ports. Despite the losses, the majority of the ships of Convoy PQ 16 did arrive, most ships to Murmansk (30 May 1942) and eight[clarification needed] ships to Archangelsk (1 June 1942). The convoy delivered so much war materiel that the Germans made greater efforts to disrupt later convoys. The heavy lift ships from Convoy PQ 16 including SS Empire Elgar stayed at Archangelsk and Molotovsk unloading ships for over 14 months.

The empty ships of QP 12, on a simultaneous return journey from Russia, had a comparatively uneventful passage; one Russian ship had to turn back and the rest reached Reykjavik on 29 May. Fifty ships had sailed in the convoys and seven had been sunk. Tovey, the commander of the Home Fleet wrote that "This success was beyond expectation." and Admiral Karl Dönitz, the commander of the German U-boat arm (Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote) acknowledged that the convoy escorts had thwarted the U-boats. An exaggerated claim by the Luftwaffe that PQ 16 had been sunk, led Dönitz to the view that aircraft would be more effective in anti-convoy operations during the summer. Onslow, the British escort commander wanted more CAM ships or escort carriers and more anti-aircraft ships on Arctic convoys, because anti-aircraft defence had become just as important as the defence against U-boats and surface ships, given the greater number of Luftwaffe aircraft based in northern Norway.[13]

In 2001 Adam Claasen wrote that the losses inflicted on PQ 16 amounted to half the total of ships sunk by the Luftwaffe during April and May, the reinforcement of Luftflotte 5 and the longer hours of daylight, putting Arctic onvoys at an increasing disadvantage. Hitler anticipated an attempted landing in Norway and ordered that a maximum effort be made against the ships. Stumpff committed the largest air effort against an Arctic convoy since operations had begun.[12] Luftflotte 5 had refined its anti-shipping tactics and used the Golden Comb (Goldene Zange) tactic of combined dive-bombing and torpedo-bombing attacks, the torpedo-bombers flying in line abreast and releasing their torpedos in a salvo. The torpedo-bombers had conducted their first operation against PQ 15 and sunk three ships. The Germans sent 101 Ju 88s and seven He 111 torpedo-bombers against PQ 16 and claimed nine ships sunk, six more so badly damaged that they were claimed as probably sunk and sixteen merchant ships damaged. The Luftflotte 5 diarist wrote,

Thus supplies to Russia from Britain and America have been dealt a severe blow. [27 May 1942] ....the correct combination of torpedo and diving attacks could bring about special success at the cost of modest losses. [1 June 1942][20]

and the Kriegsmarine staff wrote "...the enemy has learned unmistakably what risks he takes by bringing strong expeditionary forcess into the range of the Luftwaffe." under the impression that the convoy had been sunk but only five ships had been sunk by the bombers and one by a torpedo-bomber and one forced to turn back. The U-boats had been at a disadvantage in the perpetual daylight and were easily repulsed by the convoy escorts.[21]

In media[]

In his book The Year of Stalingrad (1946) the British war correspondent Alexander Werth described his experience of Convoy PQ 16 on SS Empire Baffin, which was bombed and damaged by near misses but reached Murmansk under its own power.[22]

Merchant and accompanying ships[]

| Name | Flag | Tonnage (GRT) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alamar | 5,689 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| Alcoa Banner (1919) | 5,035 | Alcoa Steamship Company | |

| American Press (1920) | 5,131 | ||

| American Robin (1919) | 5,172 | ||

| Arcos (1918) | 2,343 | ||

| Atlantic (1939) | 5,414 | ||

| RFA Black Ranger | 3,417 | Ranger-class fleet support oiler with 2,600 long tons (2,600 t) fuel oil capacity | |

| Carlton (1920) | 5,127 | Damaged by near-misses. Towed back to Iceland by Northern Spray. | |

| Chernyshevski (1919) | 3,588 | ||

| City Of Joliet (1920) | 6,167 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| City Of Omaha (1920) | 6,124 | ||

| Empire Baffin (1941) | 6,978 | Damaged by near-misses. | |

| Empire Elgar (1942) | 2,847 | ||

| Empire Lawrence (1941) | 7,457 | Sunk by aircraft. Carried one catapult-launched Hawker Sea Hurricane | |

| Empire Purcell (1942) | 7,049 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| Empire Selwyn (1941) | 7,167 | ||

| Exterminator (1924) | 6,115 | Owned by U.S. War Shipping Administration | |

| Heffron (1919) | 7,611 | ||

| Hybert (1920) | 6,120 | ||

| John Randolph (1941) | 7,191 | ||

| Lowther Castle (1937) | 5,171 | Sunk by aircraft (aerial torpedo) | |

| Massmar (1920) | 5,828 | ||

| Mauna Kea (1919) | 6,064 | ||

| Michigan (1920) | 6,419 | ||

| Minotaur (1918) | 4,554 | ||

| Mormacsul (1920) | 5,481 | Sunk by aircraft | |

| Nemaha (1920) | 6,501 | ||

| Ocean Voice (1941) | 7,174 | Convoy Commodore's vessel Suffered bomb damage but reached port | |

| Pieter De Hoogh (1941) | 7,168 | ||

| Revolutsioner (1936) | 2,900 | ||

| Richard Henry Lee (1941) | 7,191 | ||

| Shchors (1921) | 3,770 | ||

| Stari Bolshevik (1933) | 3,974 | Suffered bomb damage but reached port | |

| Steel Worker (1920) | 5,685 | Reached Murmansk but struck a mine .[24] | |

| Syros (1920) | 6,191 | Sunk by U-703 | |

| West Nilus (1920) | 5,495 | ||

| HMS Alynbank | Auxiliary anti-aircraft cruiser. Escort 23–30 May[e] |

Close convoy escort[]

| Name | Flag | Ship type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Hazard | Minesweeper | 21–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Lady Madeleine (FY 283) | ASW trawler | 21 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS St Elstan (FY 240) | ASW trawler | 21 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS Retriever (FY 261) | ASW trawler | 21–25 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS Northern Spray (FY 129) | ASW trawler | 21–26 May; Western Local Escort | |

| HMS Achates | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Ashanti | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort Senior Officer Escort | |

| HMS Martin | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Volunteer | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| ORP Garland | Destroyer | 23–27 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Honeysuckle | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Roselys | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Starwort | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Hyderabad | Corvette | 23–30 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Seawolf | Submarine | 23–29 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Trident | Submarine | 23–29 May; Ocean Escort | |

| HMS Bramble | Minesweeper[f] | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| HMS Gossamer | Minesweeper | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| Minesweeper | 29–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | ||

| HMS Seagull | Minesweeper | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| Grozny | Destroyer | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| Destroyer | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | ||

| Sokrushitelny | Destroyer | 28–30 May; Eastern Local Escort | |

| RFA Black Ranger | Fleet Oiler | Force "Q". Detached on 27 May to return to Scapa Flow | |

| HMS Ledbury | Destroyer | 23–30 May; Force "Q", escorted RFA Black Ranger |

Cruiser covering force[]

| Name | Flag | Ship type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Kent | Heavy cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Norfolk | Heavy cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Liverpool | Light cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Nigeria | Light cruiser | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Marne | Destroyer | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Onslow | Destroyer | 23–26 May | |

| HMS Oribi | Destroyer | 23–26 May |

Distant covering force[]

| Name | Flag | Ship type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMS Victorious | Aircraft carrier | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Duke of York | Battleship | 23–29 May | |

| USS Washington | Battleship | 23–29 May | |

| USS Wichita | Heavy cruiser | 23–29 May | |

| HMS London | Heavy cruiser | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Blankney | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Eclipse | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Faulknor | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Fury | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Icarus | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Intrepid | Destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Lamerton | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Middleton | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| HMS Wheatland | Escort destroyer | 23–29 May | |

| USS Mayrant | Destroyer | 24–29 May | |

| USS Rhind | Destroyer | 24–29 May | |

| USS Rowan | Destroyer | 24–29 May | |

| USS Wainwright | Destroyer | 24–29 May |

See also[]

- "HMS Ulysses" 1955 novel by Alastair MacLean

- Finnish radio intelligence intercepted planned route of the convoy.

- List of shipwrecks in May 1942

Notes[]

- ^ In October 1941, the unloading capacity of Archangel was 300,000 long tons (304,814 t), Vladivostok (Pacific Route) 140,000 long tons (142,247 t) and 60,000 long tons (60,963 t) in the Persian Gulf (for the Persian Corridor route) ports.[2]

- ^ The codebooks were carried in a weighted bag which was to be dumped overboard to prevent capture.

- ^ By the end of 1941, 187 Matilda II and 249 Valentine tanks had been delivered, comprising 25 percent of the medium-heavy tanks in the Red Army, making 30–40 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks defending Moscow. In December 1941, 16 per cent of the fighters defending Moscow were Hawker Hurricanes and Curtiss Tomahawks from Britain; by 1 January 1942, 96 Hurricane fighters were flying in the Soviet Air Forces (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily, VVS). The British supplied radar apparatus, machine tools, ASDIC and other commodities.[5]

- ^ Z—Zerstörer denotes a heavy fighter or destroyer Staffel.

- ^ A 5000 grt merchant vessel converted to carry eight 4-inch guns and eight 2-pdr (40 mm) guns[25]

- ^ Designated "fleet minesweeping sloops", they were used with the Arctic convoys as both minesweepers and anti-submarine escorts

Footnotes[]

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Howard 1972, p. 44.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Edgerton 2011, p. 75.

- ^ "Russian Convoys 1941-45", Campaign Summaries of World War 2, naval-history.net

- ^ a b Hinsley 1994, pp. 141, 145–146.

- ^ Hinsley 1994, pp. 126, 135.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Roskill 1962, p. 132.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Woodman 2004, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005, p. 167.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 146–148.

- ^ a b c Woodman 2004, pp. 149–158.

- ^ Claasen 2001, p. 203.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Werth 1946, pp. 1–44.

- ^ "Convoy PQ.16". Arnold Hague Convoy Database. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "Convoy PQ.16". Convoyweb. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "HMS Alynbank (F 84)". uboat.net. Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

References[]

- Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939–42. Vol. I. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35260-8.

- Claasen, A. R. A. (2001). Hitler's Northern War: The Luftwaffe's Ill-fated Campaign, 1940–1945. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1050-2.

- Edgerton, D. (2011). Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources and Experts in the Second World War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9918-1.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Howard, M. (1972). Grand Strategy: August 1942 – September 1943. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630075-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Kemp, Paul (1993). Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-130-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Ransome Wallis, R. (1973). Two Red Stripes. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 978-0-7110-0461-0.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (2005) [1972]. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (3rd rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-257-7.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: The War at Sea 1939–1945. Vol. II (3rd impr. ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986. Retrieved 4 June 2018 – via Hyperwar.

- Schofield, Bernard (1964). The Russian Convoys. London: BT Batsford. OCLC 906102591 – via Archive Foundation.

- Werth, A. (1946). The Year of Stalingrad: An Historical Record and a Study of Russian Mentality, Methods and Policies (online scan ed.). London: Hamish Hamilton. OCLC 901982780.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Further reading[]

- Bekker, Cajus (1973) [1964]. The Luftwaffe War Diaries [Angriffshohe 4000]. Translated by Ziegler, F. (4th US ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-22674-7. LCCN 68-19007.

- Richards, Denis; St G. Saunders, H. (1975) [1954]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight Avails. History of the Second World War, Military Series. Vol. II (pbk. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771593-6. Retrieved 4 June 2018 – via Hyperwar Foundation.

- The Rise and Fall of the German Air Force (repr. Public Record Office War Histories ed.). Richmond, Surrey: Air Ministry. 2001 [1948]. ISBN 978-1-903365-30-4. Air 41/10.

- Thiele, Harold (2004). Luftwaffe Aerial Torpedo Aircraft and Operations in World War Two. Ottringham: Hikoki. ISBN 978-1-902109-42-8.

External links[]

- Arctic convoys of World War II

- Naval battles of World War II involving the United Kingdom