Cuckoo clock

A cuckoo clock is, typically, a pendulum clock that strikes the hours with a sound like a common cuckoo call and has an automated cuckoo bird that moves with each note. Some move their wings and open and close their beaks while leaning forwards, whereas others have only the bird's body leaning forward. The mechanism to produce the cuckoo call has been in use since the middle of the 1700s and has remained almost without variation.

It is unknown who invented the cuckoo clock and where the first one was made. It is thought that much of its development and evolution was made in the Black Forest area in southwestern Germany (in the modern state of Baden-Württemberg), the region where the cuckoo clock was popularized. These clocks were exported to the rest of the world from the mid-1850s on. Today, the cuckoo clock is one of the favourite souvenirs of travellers in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and northeastern France. It has become a cultural icon of Germany.[1][2]

Characteristics[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

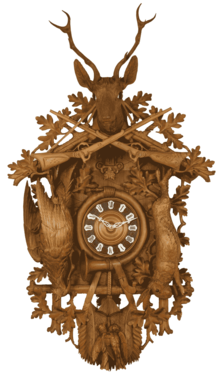

The design of a cuckoo clock is now conventional. Most are made in the "traditional style" (also known as "carved" or "chalet"), which are made to hang on a wall. In the traditional style the wooden case is decorated with carved leaves and animals. They have an automaton of a bird that appears through a small trap door when the clock strikes. The cuckoo bird is activated by the clock movement as the clock strikes by means of an arm that is triggered on the hour and half hour.[3]

There are two kinds of movements: one-day (30-hour) and eight-day clockworks. Some have musical devices, and play a tune on a Swiss music box after striking the hours and half-hours. Usually the melody sounds only at full hours in eight-day clocks and both at full and half hours in the one-day timepieces. Musical cuckoo clocks frequently have other automata which move when the music box plays. Today's cuckoo clocks are almost always weight driven, though a very few are spring driven. The weights are made of cast iron in a pine cone shape and the "cuckoo" sound is created by two tiny gedackt pipes in the clock, with bellows attached to their tops. The clock's movement activates the bellows to send a puff of air into each pipe alternately when the timekeeper strikes.[4]

In recent years, quartz battery-powered cuckoo clocks have become available. As with their mechanical counterparts, the cuckoo bird emerges from its enclosure and moves up and down, but on the quartz timepieces it also flaps its wings and open its beak while it sings. During the call the double doors open and the cuckoo emerges as usual, but only on the full hour, and they do not have a gong wire chime. The movement of the cuckoo in such clocks is regulated by an electromagnet that pulses on and off, attracting a weight, that acts as a fulcrum, connected to the tail of the plastic cuckoo bird, thus moving the bird up and down in his enclosure. Instead of the call being reproduced by the traditional bellows, it is a digital recording of a cuckoo calling in the wild (with a corresponding echo). The cuckoo call is usually accompanied by the sound of a waterfall and other birds in the background.

In musical quartz clocks, the hourly chime is followed by the replay of one of twelve popular melodies (one for each hour). Some musical quartz clocks also reproduce many of the popular automata found on mechanical musical clocks, such as beer drinkers, wood-choppers, and jumping deer.

Uniquely, quartz cuckoo clocks often include a sensor, so that when the lights are turned off at night they automatically silence the hourly chime. Other quartz cuckoo clocks are pre-programmed not to strike between a set of pre-determined hours. Whether this is controlled by a light sensor or pre-programmed, the function is referred to as a "night silence" feature. On quartz clocks the weights are conventionally cast in the shape of Aleppo pine cones made of plastic rather than iron, as are as the cuckoo bird and clock hands. The pendulum bob is often another carved leaf. Here, the weights and pendulum are purely ornamental as the clock is driven by battery power. As with mechanical cuckoo clocks, the dial is usually small, and typically marked with Roman numerals.

History[]

First modern cuckoo clocks[]

In 1629, many decades before clockmaking was established in the Black Forest,[5] an Augsburg nobleman by the name of Philipp Hainhofer (1578–1647) penned the first known description of a modern cuckoo clock.[6] The clock belonged to Prince Elector August von Sachsen.

Likewise, in a widely known handbook on music, Musurgia Universalis (1650), the scholar Athanasius Kircher describes a mechanical organ with several automated figures, including a mechanical cuckoo. This book contains the first documented description—in words and pictures—of how a mechanical cuckoo works.[7] Kircher did not invent the cuckoo mechanism, because this book, like his other works, is a compilation of known facts into a handbook for reference purposes. The engraving clearly shows all the elements of a mechanical cuckoo. The bird automatically opens its beak and moves both its wings and tail. Simultaneously, there is heard the whistle—call of the cuckoo, created by two organ pipes, tuned to a minor or major third. There is only one fundamental difference from the Black Forest-type cuckoo mechanism: The functions of Kircher's bird are not governed by a count wheel in a strike train, but a pinned program barrel synchronizes the movements and sounds of the bird.

On the other hand, in 1669 Domenico Martinelli, in his handbook on elementary clocks Horologi Elementari, suggests using the call of the cuckoo to indicate the hours.[8] Starting at that time the mechanism of the cuckoo clock was known. Any mechanic or clockmaker, who could read Latin or Italian, knew after reading the books that it was feasible to have the cuckoo announce the hours.

Subsequently, cuckoo clocks appeared in regions that had not been known for their clockmaking. For instance, the Historische Nachrichten (1713), an anonymous publication generally attributed to Court Preacher Bartholomäus Holzfuss, mentions a musical clock in the Oranienburg palace in Berlin. This clock, originating in West Prussia, played eight church hymns and had a cuckoo that announced the quarter hours.[9] Unfortunately this clock, like the one mentioned by Hainhofer in 1629, can no longer be traced today.[10]

A few decades later, people in the Black Forest started to build cuckoo clocks.

First cuckoo clocks made in the Black Forest[]

It is not clear who built the first cuckoo clocks in the Black Forest,[11] but there is unanimity that the unusual clock with the bird call very quickly conquered the region. By the middle of the 18th century, several small clockmaking shops produced cuckoo clocks with wooden gears. The first Black Forest examples were created between 1740 and 1750. The earliest Black Forest examples had shields decorated with paper.[12]

It is hard to judge how large the proportion of cuckoo clocks was among the total production of modern movement Black Forest clocks. Based on the proportions of pieces surviving to the present, it must have been a small fraction of the total production.[13]

Regarding its murky origins, there are two main fables from the first two chroniclers of Black Forest horology which tell contradicting stories about it: The first is from Father Franz Steyrer, written in his "Geschichte der Schwarzwälder Uhrmacherkunst" (History of the Art of Clockmaking in the Black Forest) in 1796. He describes a meeting between two clock peddlers from Furtwangen (a town in the Black Forest) who met a travelling Bohemian merchant who sold wooden cuckoo clocks. Both the Furtwangen traders were so excited that they bought one. On bringing it home they copied it and showed their imitation to other Black Forest clock traders. Its popularity grew in the region and more and more clockmakers started producing them. With regard to this chronicle, the historian Adolf Kistner claimed in his book "Die Schwarzwälder Uhr" (The Black Forest Clock), published in 1927, that there is not any Bohemian cuckoo clock in existence to verify the thesis that this clock was used as a sample to copy and produce Black Forest cuckoo clocks. Bohemia had no fundamental clockmaking industry during that period.

The second story is related by another priest, Markus Fidelis Jäck, in a passage extracted from his report "Darstellungen aus der Industrie und des Verkehrs aus dem Schwarzwald" (Descriptions of the Industry and the Traffic of the Black Forest), (1810) said as follows: "The cuckoo clock was invented (in 1730) by a clock-master [Franz Anton Ketterer] from Schönwald [literally "Beautiful Forest", i.e. the Black Forest]. This craftsman adorned a clock with a moving bird that announced the hour with the cuckoo-call. The clock-master got the idea of how to make the cuckoo-call from the bellows of a church organ". Unfortunately, neither Steyrer nor Jäck quote any sources for their claims, making them unverifiable.

As time went on, the second version became the more popular, and is the one generally related today, though evidence suggests its inaccuracy.[14] This type of clock is much older than clockmaking in the Black Forest. As early as 1650, the mechanical cuckoo was part of the reference book knowledge recorded in handbooks. It took nearly a century for the cuckoo clock to find its way to the Black Forest, where for many decades it remained a tiny niche product. In addition, R. Dorer pointed out in 1948 that Franz Anton Ketterer (1734–1806) could not have been the inventor of the cuckoo clock in 1730, because he had not yet been born. This statement was corroborated by Gerd Bender in the most recent edition of the first volume of his work Die Uhrenmacher des hohen Schwarzwaldes und ihre Werke (The Clockmakers of the High Black Forest and their Works) (1998) in which he wrote that the cuckoo clock was not native to the Black Forest and also stated that: "There are no traces of the first production line of cuckoo clocks made by Ketterer". Schaaf, in Schwarzwalduhren (Black Forest Clocks) (1995), provides his own research which leads to the earliest cuckoos having been built in the Franken-Niederbayern area ("Franconia and Lower Bavaria", in the southeast of Germany, forming nowadays the northern two-thirds of the Free State of Bavaria), in the direction of Bohemia (nowadays the main region of the Czech Republic), which he notes, lends credence to the Steyrer version.

Although the idea of placing an automaton cuckoo bird in a clock to announce the passing of time did not originate in the Black Forest, it is necessary to emphasize that the cuckoo clock as we know it today comes from this region located in southwest Germany whose tradition of clockmaking started in the late 17th century. The Black Forest people who created the cuckoo clock industry developed it, and still come up with new designs and technical improvements which have made the cuckoo clock a valued work of art all over the world.

Even though the functionality of the cuckoo mechanism has remained basically unchanged, the appearance has changed as case designs and clock movements evolved in the region. The now traditional Black Forest clock design, the "Schilduhr" (Shield-clock), was characterized by having a painted flat square wooden face behind which all the clockwork was attached. On top of the square was usually a semicircle of highly decorated painted wood which contained the door for the cuckoo. These usually depicted floral patterns (so-called "Rosenuhren", rose clocks) and often had a painted column, on either side of the chapter ring, others were decorated with illustrations of fruit as well. Some pieces also bore the names of the bride and bridegroom on the dial, which were normally painted by women.[15] There was no cabinet surrounding the clockwork in this model. This design was the most prevalent between the end of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century. These timekeepers were typically sold from door to door by "Uhrenträger" (Clock-peddlers, literally "clock carriers") who would carry the dials and movements on their backs displayed on huge backpacks.

Towards the middle of the nineteenth century till the 1870s, cuckoo clocks were also manufactured in the Black Forest type of clock known as "Rahmenuhr" (Framed-clock). As the name suggests, these scarce wall cuckoo clocks consisted of a picture frame, usually with a typical Black Forest scene painted on a wooden background or a sheet metal, lithography and screen-printing were other techniques used. Other common themes depicted were; hunting, love, family, death, birth, mythology, military and Christian religious scenes. Works by painters such as Johann Baptist Laule (1817–1895) and Carl Heine (1842–1882) were used to decorate the fronts of this and other types of clocks. The painting was almost always protected by a glass and some models displayed a person or an animal with blinking or flirty eyes as well, being operated by a simple mechanism worked by means of the pendulum swinging. The cuckoo normally took part in the scene painted, and would pop out in 3D, as usual, to announce the hour.

From the 1860s until the early 20th, cases were manufactured in a rich variety of styles such as; Biedermeier (some models also included a painting of a person or animal with moving eyes), Neoclassical or Georgian (certain pieces also displayed a painting), Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Art Nouveau, etc., becoming a suitable complementary piece for the bourgeois living room. These timepieces, based both on architectural and home decorative styles, are rarer than the popular ones looking like gatekeeper-houses (Bahnhäusle style clocks) and they could be mantel, wall or bracket clocks.

However, the popular house-shaped Bahnhäusleuhr (Railroad house clock) virtually forced the discontinuation of other designs within a few decades.

Early cuckoo clock, Black Forest, 1760–1780 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 03-2002)

Exemplary by Johannes Wildi, Eisenbach, c. 1780. (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 2008-024)

The so-called Shield cuckoo clock, 1790s.

Rahmenuhr by J. Laule depicting a scene of a Black Forest clockmaker's shop. Furtwangen, c. 1860 (Deutsches Uhrenmuseum, Inv. 07-0068)

A Biedermeier style cuckoo clock.

Bahnhäusle style, a successful design from Furtwangen[]

In September 1850, the first director of the Grand Duchy of Baden Clockmakers School in Furtwangen, Robert Gerwig, launched a public competition to submit designs for modern clockcases, which would allow homemade products to attain a professional appearance.

Friedrich Eisenlohr (1805–1854), who as an architect had been responsible for creating the buildings along the then new and first Badenese Rhine valley railway, submitted the most far-reaching design.[16] Eisenlohr enhanced the facade of a standard railroad-guard's residence, as he had built many of them, with a clock dial. His "Wallclock with shield decorated by ivy vines," (in reality the ornament were grapevines and not ivy) as it is referred to in a surviving, handwritten report from the Clockmakers School from 1851 or 1852, became the prototype of today's popular souvenir cuckoo clocks.

Eisenlohr was also up-to-date stylistically. He was inspired by local images; rather than copying them slavishly, he modified them. Contrary to most present-day cuckoo clocks, his case features light, unstained wood and were decorated with symmetrical, flat fretwork ornaments.

Eisenlohr's idea became an instant hit, because the modern design of the Bahnhäusle clock appealed to the decorating tastes of the growing bourgeoisie and thereby tapped into new and growing markets.

While the Clockmakers School was satisfied to have Eisenlohr's clock case sketches, they were not fully realized in their original form. Eisenlohr had proposed a wooden facade; Gerwig preferred a painted metal front combined with an enamel dial. But despite intensive campaigns by the Clockmakers School, sheet metal fronts decorated with oil paintings (or coloured lithographs) never became a major market segment because of the high cost and labour-intensive process,[17] hence only a few were produced (from the 1850s until around 1870), whether wall or mantel versions, and are nowadays sought-after collector pieces.

Characteristically, the makers of the first Bahnhäusle clocks deviated from Eisenlohr's sketch in only one way: they left out the cuckoo mechanism. Unlike today, the design with the little house was not synonymous with a cuckoo clock in the first years after 1850. This is another indication that at that time cuckoo clocks could not have been an important market segment.[17]

Only in December 1854, Johann Baptist Beha, the best known maker of cuckoo clocks of his time, sold two of them, with oil paintings on their fronts, to the Furtwangen clock dealer Gordian Hettich, which were described as Bahnhöfle Uhren ("Railroad station clocks").[18] More than a year later, on January 20, 1856, another respected Furtwangen-based cuckoo clockmaker, Theodor Ketterer, sold one to Joseph Ruff in Glasgow (Scotland, United Kingdom).

Concurrently with Beha and Ketterer, other Black Forest clockmakers must have started to equip Bahnhäusle clocks with cuckoo mechanisms to satisfy the rapidly growing demand for this type of clock. Starting in the mid-1850s there was a real boom in this market.

By 1860, the Bahnhäusle style had started to develop away from its original, "severe" graphic form, and evolve, among other designs, toward the well-known case with three-dimensional woodcarvings, like the Jagdstück ("Hunt piece", design created in Furtwangen in 1861), a cuckoo clock with carved oak foliage and hunting motives, such as trophy animals, guns and powder pouches.[19]

By 1862 the reputed clockmaker Johann Baptist Beha, started to enhance his richly decorated Bahnhäusle clocks with hands carved from bone and weights cast in the shape of fir cones.[20] Even today this combination of elements is characteristic for cuckoo clocks, although the hands are usually made of wood or plastic, white celluloid was employed in the past too. As for the weights, there was during this second half of the 19th century, a few models which featured weights cast in the shape of a Gnome and other curious forms.

Only ten years after its invention by Friedrich Eisenlohr, all variations of the house-theme had reached maturity. There were also Bahnhäusle timepieces and its derived manufactured as mantel clocks but not as many as the wall versions.

The basic cuckoo clock of today is the railway-house (Bahnhäusle) form, still with its rich ornamentation, and these are known under the name of "traditional" (or carved); which display carved leaves, birds, deer heads (Jagdstück design), other animals, etc. The richly decorated Bahnhäusle clocks have become a symbol of the Black Forest that is instantly understood anywhere in the world.

The cuckoo clock became successful and world-famous after Friedrich Eisenlohr contributed the Bahnhäusle design to the 1850 competition at the Furtwangen Clockmakers School.[14]

"Chalet" style, the Swiss contribution[]

The "Chalet" style is an invention from 1920 by Zurich Company Lötscher in Switzerland,[21] at that time they were highly valued as souvenirs. However, "what could come as a surprise however is learning that Switzerland is not in fact the home of the cuckoo clock and that the quartz clocks are made in Germany as well. The Black Forest region of southern Germany is where cuckoo clocks—mostly depicting a hunting scene—have their real nest."[21]

In the English-speaking world, cuckoo clocks are sufficiently identified with Switzerland that the film The Third Man has an oft-quoted speech (and it even had antecedents) in which the villainous Harry Lime mockingly says that "in Switzerland they had brotherly love. They had 500 years of democracy and peace. And what did that produce? The cuckoo clock."[21] A typically wrongly attributed meme by a Hollywood movie. Though, music and jewellery boxes of several sizes as well as timepieces were manufactured in the shape of a typical Swiss chalet, some of those clocks had also the added feature of a cuckoo bird and other automata.

Designer cuckoo clocks: The stylistic revolution[]

The early 21st century has seen a revitalization of this ancient icon with designs, materials, technologies, shapes and colors never seen before in cuckoo clock manufacturing.[22] These timekeepers are distinguished by its functional, schematic and minimalist aesthetic.

Although simplified designs with simple, clear lines had already been produced in the 20th century, the real boom of seeing the cuckoo clock as a designer item, where the creativity and talent of designers are freely expressed and where the only limit seems to be imagination, was initiated in the 2000s (the first examples dating back to the 1990s), particularly in Italy and Germany.[22]

As for the models, there are a great variety, many of them avant-garde and adventurous creations made of different materials and geometric shapes, such as rhombuses, squares, cubes, circles, rectangles, ovals, etc. Without carving, these clocks are usually flat and smooth. Some are painted in a single colour while others are polychromes with abstract or figurative paintings, multicolour lines and stripes, others include text and phrases, etc. About the clockwork, there are quartz, mechanical and sometimes, digital.

In the United States[]

Cuckoo clocks have been imported to the US by German immigrants for a long time, especially in the 19th century. There are two well-known cuckoo clock manufacturers in the USA: was founded in 1958 by . and operated in Bristol, Connecticut. The design of the models is clearly American. The clocks were made with that were imported from Triberg. The printed and colored paper dials of the clocks are unmistakable, as is the early American design. The clocks were designed by . A kit watch was also offered. The second is the of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which originated in the 1890s and imported German clocks. Eventually, the company switched to importing clockworks only and building cuckoo clocks in the USA.[23]

Museums[]

In Europe, museums that display collections are the Cuckooland Museum in the UK with more than 700 clocks,[24] and the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum and Dorf- und Uhrenmuseum Gütenbach in Germany. One of the biggest private collections in the United States that is open to the public is located in Minneapolis. It contains more than 300 cuckoo clocks.[25]

See also[]

- Automaton clock

- Black Forest Clock Association

- Cuckoo clock in culture

- List of largest cuckoo clocks

- Singing bird box

- Striking clock

Citations[]

- ^ Peter Neville-Hadley (2016-04-03). "Germany's Black Forest clock route full of surprises". torontosun.com. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- ^ Ross Sveback (2015-08-25). "Cuckoo for cuckoo clocks". fox9.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- ^ The American Cuckoo Clock Company (2019-03-03), What Makes the Cuckoo Clock Bird Move?, retrieved 2019-03-24

- ^ Stamp, Jimmy. "The Past, Present, and Future of the Cuckoo Clock". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

- ^ For the early history of Black Forest clockmaking, see Gerd Bender, "Die Uhrenmacher des hohen Schwarzwaldes und ihre Werke". Vol. 1 (Villingen, 1975): pp. 1–10.

- ^ Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock. A Success Story. NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 646.

- ^ Athanasius Kircher, Musurgia Universalis sive Ars magna consoni & dissoni, 2 Vol (Rome, 1650), here Vol. 2, p. 343f and Plate XXI.

- ^ Domenico Martinelli, Horologi Elementari (Venezia, 1669): p. 112.

- ^ Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz. Document No.:"I.HA, Rep. 36, Nr. 3048, fol. 21f": "In another room, where the Dutch porcelain is kept, is a singing clock, which was made by a farmer in Kaschuben, which plays eight hymns; but the quarter hours are called out by a cuckoo". See also Claudia Sommer, Schloss Oranienburg. Ein Inventar aus dem Jahre 1743where there is also a reference to a currently missing inventory of 1709. The inventory of 1702 does not yet list this clock; therefore, it is probable that it reached Oranienburg between 1702 and 1709, Verwaltung der Märkischen Schlösser).

- ^ It remains doubtful which is the oldest cuckoo clock before the bird made its appearance in the Black Forest. Again and again old iron or wooden clock movements are discovered, which have automated cuckoos that possibly predate the first wooden movement cuckoo clocks from the Black Forest. (See also Wilhelm Schneider, "Die eiserne Kuckucksuhr" (The Iron Movement Cuckoo Clock), Alte Uhren und Moderne Zeitmessung, No. 5 (1989): pp. 37–44).

- ^ Also refer to the discussion on the origin of the Black Forest cuckoo clock to: Richard Mühe, Helmut Kahlert and Beatrice Techen, Kuckucksuhren (München, 1988): pp. 7–14.

- ^ * Miller, Justin , Rare and Unusual Black Forest Clocks, (Schiffer 2012), p. 30.

- ^ Helmut Kahlert, Die Kuckucksuhren-Saga, Alte Uhren, No. 4 (1983): pp. 347–353; here p. 349.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock: A Success Story. In: NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 651.

- ^ "Pier Van Leeuwen, "Clocks from the Black Forest (1740–1900)" (2005): in the Museum of the Dutch Clock website". Antique-horology.org. 2005-10-31. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ^ The credit for first discovering Eisenlohr's original design goes to Herbert Jüttemann. See Herbert Jüttemann, Die Schwarzwalduhr, 4th ed. (Karlsruhe, 2000): p. 242.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johannes Graf, The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock. A Success Story. In: NAWCC Bulletin, December 2006: p. 649.

- ^ Wilhelm Schneider "Frühe Kuckucksuhren von Johann Baptist Beha aus Eisenbach im Hochschwarzwald" (Remembering the design of a genius. 150 years of Bahnhaeusle clocks), Alte Uhren und moderne Zeitmessung, No. 3 (1987): pp. 45–53, here p. 51.

- ^ Schneider 1987, p. 51. (Within a short time more orders for hunt pieces are recorded, specifically on October 30, November 7 and November 26, 1861.)

- ^ As per Wilhelm Schneider, who had a chance to examine the account books of Beha. See Wilhelm Schneider, "Frühe Kuckucksuhren von Johann Baptist aus Eisenbach im Hochschwarzwald" (Early cuckoo clocks by Johann Baptist Beha of Eisenbach in the high Black Forest). Alte Uhren und moderne Zeitmessung. No 3 (1987): pp. 45–53, here p. 52.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Robert Brookes (24 November 2006). "Going cuckoo about real Swiss cuckoo clocks". Berne, Switzerland: SWI swissinfo.ch, a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation SRG SSR. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Juan F. Déniz, Designer Cuckoo Clocks. In: NAWCC Bulletin, September/October 2013: p. 479" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ Boyett, David. "American Cuckoo Clock Co PA—Knierman Family". PBase. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- ^ Carlson, Leland (2015). Dull Men of Great Britain: Celebrating the Ordinary. Ebury Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-78503-090-1.

Cuckooland has more than 700 cuckoo clocks on display, each one different from the others.

- ^ Marsh, Steve (May 12, 2015). "In Search of Lost Time". Mpls.St.Paul magazine. Accessed 14 December 2021.

General bibliography[]

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1985): "Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Kuckucksuhr". In: Alte Uhren, Fascicle 3, pp. 13–21.

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1987): "Frühe Kuckucksuhren von Johann Baptist Beha in Eisenbach im Hochschwarzwald". In: Uhren, Fascicle 3, pp. 45–53.

- Mühe, Richard, Kahlert, Helmut and Techen, "Beatrice" (1988): Kuckucksuhren. München.

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1988): "The Cuckoo Clocks of Johann Baptist Beha". In: Antiquarian Horology, Vol. 17, pp. 455–462.

- Schneider, Wilhelm, Schneider, Monika (1988): "Black Forest Cuckoo Clocks at the Exhibitions in Philadelphia 1876 and Chicago 1893". In: Watch & Clock Bulletin, Vol. 30/2, No. 253, pp. 116–127 and 128–132.

- Schneider, Wilhelm (1989): "Die eiserne Kuckucksuhr". In: Uhren, 12. Jg., Fascicle 5, pp. 37–44.

- Kahlert, Helmut (2002): "Erinnerung an ein geniales Design. 150 Jahre Bahnhäusle-Uhren". In: Klassik-Uhren, F. 4, pp. 26–30.

- Graf, Johannes (December 2006): "The Black Forest Cuckoo Clock: A Success Story". In: Watch & Clock Bulletin. Volume 49, Issue 365. pp. 646–652.

- Miller, Justin (2012). Rare and Unusual Black Forest Clocks. Atglen, Penn.: Schiffer Pub. ISBN 9780764340918. OCLC 768166840. pp. 27–103.

- Scholz, Julia (2013): Kuckucksuhr Mon Amour. Faszination Schwarzwalduhr. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag, 160 p. ISBN 978-3-8062-2797-0.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuckoo clocks. |

- Black Forest

- Clock designs

- Culture of Baden-Württemberg

- Swiss culture

- Symbols