Cult of the Supreme Being

| Cult of the Supreme Being | |

|---|---|

| Culte de l'Être suprême | |

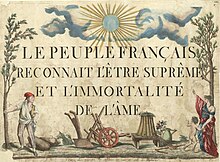

"The French people recognize the Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul" (printed in 1794) | |

| Classification | Deism |

| Orientation | Voltairean |

| Polity | None; absent |

| Governance | None; absent |

| Region | France |

| Language | French |

| Headquarters | Paris |

| Founder | Maximilien Robespierre |

| Origin | 7 May 1794 |

| Merged into | Theophilanthropy |

| Defunct | 28 July 1794 |

| Members | Unknown |

| Church buildings | None; absent |

| Deism |

|---|

The Cult of the Supreme Being (French: Culte de l'Être suprême)[note 1] was a form of deism established in France by Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution. It was intended to become the state religion of the new French Republic and a replacement for Roman Catholicism and its rival, the Cult of Reason. It went unsupported after the fall of Robespierre and was officially proscribed when Napoleon restored Catholicism in France.

Origins[]

The French Revolution had occasioned many radical changes in France, but one of the most fundamental for the hitherto Catholic nation was the official rejection of religion. The first new major organized school of thought emerged under the umbrella name of the Cult of Reason. Advocated by radicals like Jacques Hébert and Antoine-François Momoro, the Cult of Reason distilled a mixture of largely atheistic views into an anthropocentric philosophy. No gods at all were worshipped in the Cult of Reason—the guiding principle was devotion to the abstract concept of Reason itself.[1]

This rejection of all godhead appalled Maximilien Robespierre. Though he was no admirer of Catholicism, he had a special dislike for atheism.[2] He thought that belief in a supreme being was important for social order, and he liked to quote Voltaire: "If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him".[3] To him, the Cult of Reason's philosophical offenses were compounded by the "scandalous scenes" and "wild masquerades" attributed to its practice.[4] In late 1793, Robespierre delivered a fiery denunciation of the Cult of Reason and of its proponents[5] and proceeded to give his own vision of proper Revolutionary religion. Devised almost entirely by Robespierre, the Cult of the Supreme Being was authorized by the National Convention on 7 May 1794 as the civic religion of France.[6][7][8]

Religious tenets[]

Robespierre believed that reason is only a means to an end, and the singular end is virtue. He sought to move beyond simple deism (often described as Voltairean by its adherents) to a new and, in his view, more rational devotion to the godhead. The primary principles of the Cult of the Supreme Being were a belief in the existence of a god and the immortality of the human soul.[9] Though not inconsistent with Christian doctrine, these beliefs were put to the service of Robespierre's fuller meaning, which was of a type of civic-minded, public virtue he attributed to the Greeks and Romans.[10] This type of virtue could only be attained through active fidelity to liberty and democracy.[11] Belief in a living god and a higher moral code, he said, were "constant reminders of justice" and thus essential to a republican society.[12]

Revolutionary impact[]

Robespierre used the religious issue to publicly denounce the motives of many radicals not in his camp, and it led, directly or indirectly, to the executions of Revolutionary de-Christianisers like Hébert, Momoro, and Anacharsis Cloots.[4] The establishment of the Cult of the Supreme Being represented the beginning of the reversal of the wholesale de-Christianization process that had been looked upon previously with official favour.[13] Simultaneously it marked the apogee of Robespierre's power. Though in theory he was just an equal member of the Committee of Public Safety, Robespierre at this point possessed an unrivalled national prominence.[14]

Festival of the Supreme Being[]

To inaugurate the new state religion, Robespierre declared that 20 Prairial Year II (8 June 1794) would be the first day of national celebration of the Supreme Being, and future republican holidays were to be held every tenth day—the days of rest (décadi) in the new French Republican Calendar.[6] Every locality was mandated to hold a commemorative event, but the event in Paris was designed on a massive scale. The festival was organized by the artist Jacques-Louis David and took place around a man-made mountain on the Champ de Mars.[15] Robespierre assumed full leadership of the event, forcefully—and, to many, ostentatiously[16]—declaring the truth and "social utility" of his new religion.[17] While earlier Revolutionary festivals were more spontaneous, the Festival of the Supreme Being was meticulously planned. Historian Mona Ozouf has noted how the "creaking stiffness" of the event has been seen by some to foreshadow "the sclerosis of the Revolution."[18]

Legacy[]

The Cult of the Supreme Being and its festival may have contributed to the Thermidorian Reaction and the downfall of Robespierre.[17] With his death at the guillotine on 28 July 1794, the cult lost all official sanction and disappeared from public view.[19] It was officially banned by Napoleon Bonaparte on 8 April 1802 with his , Year X.[20]

See also[]

- Cult of Reason

- Deism

- Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution

- Gottgläubig

- God-Building

- Theophilanthropy

Notes[]

- ^ The word "cult" in French (culte) means "a form of worship", without any of its negative or exclusivist implications in English: Robespierre intended it to appeal to a universal congregation.

References[]

- ^ Kennedy, p. 343: "Momoro explained, 'Liberty, reason, truth are only abstract beings. They are not gods....'"

- ^ Scurr, p. 293.

- ^ Scurr, p. 294.

- ^ a b Kennedy, p. 344.

- ^ Kennedy, p. 344: "Robespierre lashed out against de-Christianization in the Convention...."

- ^ a b Doyle, p. 276.

- ^ Neely, p. 212: "(T)he Convention authorized the creation of a civic religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being. On 7 May, Robespierre introduced the legislation...."

- ^ Jordan, pp. 199ff.

- ^ Kennedy, p. 345.: "Robespierre followed a consistent line of argument...(that) God exists and that the soul is immortal."

- ^ Žižek, p. 111: "I [Robespierre] am talking about the public virtue that worked such prodigies in Greece and Rome, and that should produce far more astonishing ones in republican France...."

- ^ Lyman, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Doyle, p. 276.: "[Robespierre] proclaim[ed] that the French people recognized the existence of a Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul. These principles, declared Robespierre to applause, were a continual reminder of justice, and were therefore social and republican." See also p.262: "[Robespierre] believed that religious faith was indispensable to orderly, civilized society".

- ^ Kennedy, p. 344.: "Robespierre's influence was such that the de-Chistianization movement rapidly slackened...."

- ^ Doyle, p. 277.: "He seemed to be speaking for the Committee of Public Safety more and more, and was certainly better known in the country at large than any of his colleagues. At Orléans, as well as in Paris, the Festival of the Supreme Being took place to cries of "Vive Robespierre"."

- ^ Hanson, p. 95: "...[T]he Champ de Mars where David had created an enormous symbolic mountain."

- ^ Doyle, p. 277: "'Look at the bugger,' muttered Thuriot, an old associate of Danton. 'It's not enough for him to be master, he has to be God.'"

- ^ a b Kennedy, p. 345.

- ^ Ozouf, Mona. (1988). Festivals and the French Revolution. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0674298837. OCLC 16005069.

- ^ Neely, p. 230: "The fall of Robespierre brought an end to the Cult of the Supreme Being with which he had been closely identified. The new civic religion... had not had a chance to win many converts."

- ^ Doyle, p. 389.

Bibliography[]

- Doyle, William (1989). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822781-6.

The Oxford History of the French Revolution.

- Hanson, Paul R. (2004). Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8108-5052-1.

cult of the supreme being.

- Jordan, David P. (1985). The Revolutionary Career of Maximilien Robespierre. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-41037-1.

- Kennedy, Emmet (1989). A Cultural History of the French Revolution. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04426-3.

A Cultural History of the French Revolution.

- Lyman, Richard W.; Spitz, Lewis W. (1965). Major Crises in Western Civilization, Vol. 2. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Neely, Sylvia (2008). A Concise History of the French Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-7425-3411-7.

The Oxford History of the French Revolution.

- Robespierre, Maximilien. 1793 [Year 2 of the Republic]. "The Festival of the Supreme Being," translated by M. Abidor. Receuil d'hymnes Républicaines. Paris: Chez Barba.

- Scurr, Ruth (2006). Fatal Purity: Robespierre and the French Revolution. Henry Holt. ISBN 9780805082616.

- Žižek, Slavoj (2007). Robespierre: Virtue and Terror. New York: Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-584-5.

Further reading[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cult of the Supreme Being. |

- Maclear, J. F. (1995). "Decree on Worship of the Supreme Being". Church and State in the Modern Age: A Documentary History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508681-2.

- Martin, Elma Gillespie (1918). Rousseau's Religious Ideas with Reference to the Religious Ideas Prominent in the Revolution and to Their Influence on Robespierre and Saint Just (Doctoral dissertation, Cornell University). Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Halsall, Paul. [1996 January 26] 2020 January 21. "Maximilien Robespierre: The Cult of the Supreme Being" (rev.). Internet Modern History Sourcebook. New York: Fordham University.

- Robespierre, Maximilien. 1793 [Year 2 of the Republic]. "The Festival of the Supreme Being," translated by M. Abidor. Receuil d'hymnes Républicaines. Paris: Chez Barba.

External links[]

- The Festival of the Supreme Being at marxists.org Robespierre's two speeches at the Festival In English

- 1794 events of the French Revolution

- Anti-Catholicism in France

- Conceptions of God

- Deism

- Maximilien Robespierre

- Religion and the French Revolution

- Religious organizations disestablished in the 18th century

- Religious organizations established in 1794