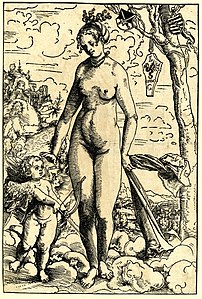

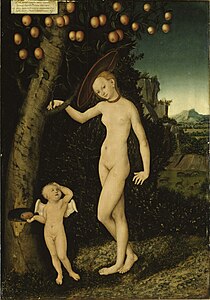

Cupid complaining to Venus

Cupid complaining to Venus is an oil painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Nearly 20 similar works by Cranach and his workshop are known, from the earliest dated version in Güstrow Palace of 1527 to one in the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, dated to 1545, with the figures in a variety of poses and differing in other details. The Metropolitan Museum of Art notes that the number of extant versions suggests that this was one of Cranach's most successful compositions.

A version acquired by the National Gallery, London in 1963 is perhaps the earliest example. Although undated, experts have dated it to c.1526-7. It is more elaborate than the others, and in a larger format than most, except for the similarly sized Güstrow version and a larger (life size) version at the Galleria Borghese, Rome dated to 1531. Cranach had painted Venus and Cupid together since at least his 1509 painting now held by the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

National Gallery painting[]

The work in the National Gallery was originally painted on a wooden panel. The painting is undated, but Koepplin and Falk have suggested a date of 1526–7. Known in German as Venus mit Amor als Honigdieb ("Venus with Cupid as a honey thief"), it depicts two classical gods of love, standing naked amid a verdant landscape under a blue sky. The work has been interpreted as an allegory of the pleasure and pains of love, and possibly also a warning of the risks of venereal disease.

The winged infant Cupid stands the left of a tree which bears red apples. He is holding a honeycomb, possibly taken from a hole towards the bottom of the tree's trunk. He is being assailed by honeybees, infuriated by his theft of their sweet treasure. Venus is depicted as a voluptuous woman to the right of the tree. She is holding up a branch with her left hand, and rests her left foot on another. A stone below Venus's raised foot bears an inscription of a winged serpent with a ring in its mouth, a heraldic device granted to Cranach by Frederick the Wise in 1508. Venus is wearing only a hat of red and gold cloth decorated with a wide circle of ostrich plumes, and two necklaces: a gold chain and a jewelled choker. The pose of Venus, and the apples, allude to paintings of Eve by Cranach.

In the background, a stag and hind hide among the trees to the left, and fortifications on and beside a rocky outcrop to the right are reflected in water.

The subject is inspired by Idyll XIX "Keriokleptes" ("The Honeycomb Stealer") attributed to the Ancient Greek poet Theocritus, in which Cupid complains of the painful stings inflicted by the small insects, and Venus laughingly compares them to the bittersweet darts of love shot by Cupid himself. The text was first translated into German in the 1520s, and the subject may have been suggested to Cranach by a German patron. To the top right is a Latin inscription painted with black words directly on the blue sky, making it difficult to read, but also suggesting this may be the earliest version of the painting, as later versions place the inscription on a white panel. The four line inscription is taken from Latin translations of Theocritus, variously attributed to Ercole Strozzi and Philip Melanchthon or to Georg Sabinus, which reads:

| Latin text | Reconstruction | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

|

DVM PVER ALVE[...] IN C[...] |

DVM PVER ALVEOLO FVRATVR MELLA CVPIDO |

As Cupid was stealing honey from the hive |

The paint was applied to a chalk ground of powdered calcium carbonate bound with glue, which was primed with white lead. Hints of red underdrawing are still visible. The pigments used include azurite and lead white for the blue sky, lead-tin-yellow and verdigris for the green leaves, lead white with red lake and vermilion for the red apples, with yellow highlights of lead-tin yellow, and black underpainting.

In June 1962 the of New York transferred it a Masonite support, with the back veneered in mahogany and cradled to resemble a work on a wooden board. It now measures 82.1 by 55.8 centimetres (32.3 in × 22.0 in). It was cleaned and restored in July 1963.

History[]

The provenance of the National Gallery version is not known for nearly four centuries after its execution in the early 16th century until it was sold from the collection of the Frankfurt art collector after his death in 1909.

At the 1909 sale, it may have been acquired by a Chemnitz businessman Hans Hermann Vogel, and later sold by his widow in 1935 to , president of the Reichsverbandes der deutschen Automobilindustrie (German Association of the Automotive Industry), when it was described as a work by Lucas Cranach depicting Venus und Amor als Honigdieb. It may have been acquired by Adolf Hitler c.1937: indeed, it may be the Cranach that Hitler bought using royalties from his 1925 autobiographical book Mein Kampf. It appears to be the work by Cranach photographed in Hitler's private collection in Berchtesgaden.

The painting was acquired in somewhat unclear circumstances by the American war correspondent in 1945. According to later accounts, Americans soldiers guarding a warehouse in southern Germany allowed her to select a work and take it away. The painting was sold through in New York in 1962, and bought by the National Gallery the following year.[1]

The provenance of the painting from 1909 to 1945 remains uncertain. In 2006 it was identified as possibly being expropriated Nazi plunder. The heirs of the original owners might have a claim for restoration of the painting; if there are any, their identify is not known.

Venus and Cupid, 1508–09

Venus and Cupid, Hermitage, 1509

Version at Schloss Güstrow, 1527

National Gallery, London, 1529

Version at Fondation Bemberg Toulouse, 1531

Version at Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, 1537

Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, after 1537

Metropolitan Museum of Art, follower, 1580-1620

Prague, follower, 1575-1615

References[]

- ^ Bailey, Martin. "Revealed: National Gallery's Cranach is war loot". www.lootedart.com. Archived from the original on 2020-01-23. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Venus with Cupid stealing honey by Lucas Cranach (I). |

- Lucas Cranach the Elder, Cupid complaining to Venus, National Gallery

- Lucas Cranach the Elder, Cupid Complaining to Venus – Susan Foister, National Gallery

- Cupid complaining to Venus, Google Arts and Culture

- Cupid complaining to Venus, National Gallery, London, Cranach Digital Archive

- Lucas Cranach d.Ä. - Venus und Amor als Honigdieb, Technische Universität Berlin, Magistra Artium Melanie List, 2006

- Venus with Cupid the Honey Thief (copy after Lucas Cranach the Elder), Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Venus with Cupid the Honey Thief, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cranach Digital Archive

- Venus and Cupid as Honey Thief, Museum Schloss Güstrow, Cranach Digital Archive

External links[]

- Paintings by Lucas Cranach the Elder

- 1526 paintings

- Christian paintings

- Collections of the National Gallery, London

- Paintings of Venus

- Paintings of Cupid