Cus D'Amato

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

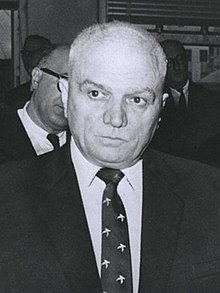

Cus D'Amato | |

|---|---|

D'Amato in 1959 | |

| Born | Constantine D'Amato January 17, 1908 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | November 4, 1985 (aged 77) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Boxing manager and trainer |

| Years active | 1933–1985 |

Constantine "Cus" D'Amato (January 17, 1908 – November 4, 1985) was an American boxing manager and trainer who handled the careers of Mike Tyson, Floyd Patterson, and José Torres, all of whom went on to be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.[1] Several successful boxing trainers, including Teddy Atlas and Kevin Rooney, were tutored by D'Amato. He was a proponent of the peek-a-boo style of boxing, in which the fighter holds his gloves close to his cheeks and pulls his arms tight against his torso, which was criticized by some because it was believed that an efficient attack could not be launched from it.[2][3]

Early life[]

Constantine D'Amato was born into an Italian-American family in the New York City borough of the Bronx on January 17, 1908.[4] His father, Damiano, delivered ice and coal in the Bronx using a horse and cart.[5] At a young age, D'Amato became very involved and interested in Catholicism, and even considered becoming a priest during his youth.

He had a brief career as an amateur boxer, fighting as a featherweight and lightweight, but was unable to get a professional license because of an eye injury he had suffered in a street fight. Although some people believe the eye injury originated from a beating from his father,[citation needed] Cus stated in an interview that he did not hold any grudges towards his father beating him, as the beatings made him a better and a more disciplined man.[5]

Career[]

At age 22, D'Amato opened the Empire Sporting Club with Jack Barrow at the Gramercy Gym.[4] He lived in the gym for years. According to D'Amato, he spent his time at the gym waiting for a "champion", but his best fighters were routinely poached by "connected" managers. One fighter discovered by D'Amato was Italian-American Rocky Graziano, who signed with other trainers and managers and went on to become middleweight champion of the world.[2] D'Amato also confronted boxing politics and decided, along with his friend Howard Cosell, to thwart the International Boxing Club of New York (IBC). Suspicious to the point of paranoia, he refused to match his fighter in any bout promoted by the IBC.[4] The IBC was eventually found to be in violation of and was dissolved.[4][6]

Personal life[]

In the early 1970s, while looking for a mansion big enough to accommodate about 12 of his most aspiring trainees and occasionally receive around 50 others, D'Amato (then in his 60s) met his wife-to-be Camille Ewald; she was thinking about selling her house, a 14-room Victorian mansion, after her family left. D'Amato came around and made a proposition to her. He oversaw all the training and managing of his fighters, while she was responsible for cooking and household chores.[7]

Notable boxers trained[]

Floyd Patterson[]

Under D'Amato's tutelage, Floyd Patterson captured the Olympic middleweight gold medal in the 1952 Helsinki games. D'Amato then guided Patterson through the professional ranks, maneuvering Patterson into fighting for the title vacated by Rocky Marciano. After beating Tommy "Hurricane" Jackson in an elimination fight, Patterson faced Light Heavyweight Champion Archie Moore on November 30, 1956, for the World Heavyweight Championship. He beat Moore by a knockout in five rounds and became the youngest World Heavyweight Champion in history at the time, at the age of 21 years, 10 months, three weeks and five days. He was the first Olympic gold medalist to win a professional Heavyweight title.

Patterson and D'Amato split after Patterson's second consecutive 1st-round KO loss to Sonny Liston, although his influence over the former two-time champion had already begun to diminish.[5]

José Torres[]

D'Amato also managed José Torres who, in May 1965 at Madison Square Garden, defeated International Boxing Hall Of Fame member Willie Pastrano to become world Light Heavyweight champion.[8] With the victory Torres became the third Puerto Rican world boxing champion in history and the first Latin American to win the world Light Heavyweight title.

Mike Tyson[]

I think of a light bulb on Cus that says: 'I have found my Sonny Liston. I'm gonna do everything to coddle him, to protect him, to develop him, because he is my revenge on the world.'

—Jack Newfield on Tyson's special role in the D'Amato's life[9]

After Patterson and Torres' careers ended, D'Amato worked in relative obscurity. He eventually moved to Catskill, New York, where he opened a gym, the Catskill Boxing Club.[4] There he met and began to work with the future heavyweight champion, "Iron" Mike Tyson, who was in a nearby reform school.[2][10] He adopted Tyson after Tyson's mother died. D'Amato trained him over the next few years, encouraging the use of peek-a-boo style boxing, with the hands in front of the face for more protection. D'Amato was briefly assisted by Teddy Atlas, and later Kevin Rooney, a protégé of D'Amato, who emphasized elusive movement.

It is unclear at exactly which age (11 or 12) Tyson first became seriously interested in becoming a professional boxer. "Irish" Bobby Stewart, a former Golden Gloves Champion, was approached by Tyson while working as a counselor at the Tryon School For Boys. Tyson knew of Stewart's former boxing glory and specifically asked to speak with Stewart who immediately took on a gruff attitude of the subject after witnessing Tyson's terrible behavior in his first days at the school. Bobby Stewart introduced Mike Tyson to D'Amato when Tyson was around 12 or 13 years old, after Stewart stated he had taught Tyson all he could about boxing technique and skill.[11][12] D'Amato died a little over a year before Tyson became the youngest world heavyweight titleholder in history at the age of 20 years four months, thus supplanting Patterson's record.[5] Rooney would later guide Tyson to the heavyweight championship twelve months after D'Amato's death. Footage of D'Amato can be seen in Tyson, a 2008 documentary. Tyson credits D'Amato with building his confidence and guiding him as a father figure.[13]

Death[]

D'Amato died of pneumonia at Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan on November 4, 1985. He was 77.[3]

Legacy[]

Cus D'Amato Memorial Award[]

Cus D'Amato Memorial Award was established by the Boxing Writers Association of America. The first was presented to Mike Tyson at the group's 61st annual dinner, May 16, 1986.[14]

Science of Victory Marathon[]

From October 26, 2017, through November 4, 2017, an international, online "Science of Victory" marathon was dedicated to the memory of Cus D'Amato. Journalists and boxers from Russia, Ukraine, Italy, Spain, Germany and the U.S., including Silvio Branco, Patrizio Oliva, Dr. Antonio Graceffo, Avi Nardia, and .[15] The marathon promoted the book Non-compromised Pendulum by Tom Patti and Dr. Oleg Maltsev, which reviewed Cus D'Amato's training style.[16][17][18]

Portrayals in film, theater, fiction[]

George C. Scott portrayed D'Amato in the 1995 HBO movie Tyson.

KNOCKOUT: The Cus D'Amato Story, is a stage and screenplay based on the life of Cus D'Amato, from a concept by boxing trainer Kevin Rooney and written by Dianna Lefas.

The biography Confusing The Enemy[5] tells the story of D'Amato.[1]

Commemoration[]

In 1993, the 14th Street Union[1] Square Local Development Corporation named part of 14th Street, where D'Amato's Gramercy Gym was located, Cus D'Amato Way.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brozan, Nadine (October 29, 1993). "CHRONICLE". The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Heller, Peter (1995). Bad Intentions: The Mike Tyson Story. Da Capo Press. pp. 17–20, 26, 51. ISBN 0-306-80669-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Boxing Manager Cus D'Amato Dies at 77". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Roberts, James (March 14, 2003). The Boxing Register: International Boxing Hall of Fame Official Record Book (3rd ed.). McBooks Press. ISBN 978-1590130209.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Weiss, Scott (August 1, 2013). Confusing The Enemy - The Cus D'Amato Story. Acanthus. ISBN 978-0989000123.

- ^ "D'Amato Misses on Long Shot". The New York Times. January 8, 1982.

- ^ Watch Me Now: A Documentary by Michael Marton (1983).

- ^ "Hall of Fame Friday: Jose Torres". The Ring. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ ESPN SportsCentury – Mike Tyson

- ^ Tyson, Mike (May 30, 2017). Iron Ambition: My Life with Cus D'Amato. Blue Rider Press. ISBN 978-0399177033.

- ^ Heller, Peter(1988). "Bad Intentions: The Mike Tyson Story," p. 13. Da Capo Press, New York, 1988.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (August 3, 1987). "Sports of the Times; 'Time for the New Trainers'". The New York Times.

- ^ Graham Bensinger (March 3, 2016). "Emotional Mike Tyson on trainer who made him champ". Retrieved July 2, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Berger, Phil (May 20, 1986). "Tyson Named Best Rookie". The New York Times. p. 5. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ Guests of the project noncompromisedpendulum.com

- ^ Online marathon dedicated to memory of legendary trainer Cus D'Amato www.worldboxingnews.net

- ^ Internationales Projekt «die Wissenschaft des Sieges»[permanent dead link] www.boxen1.com

- ^ Unique International Project "Science Of Victory" Archived December 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine worldofmartialarts.pro

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cus D'Amato. |

- 1908 births

- 1985 deaths

- Sportspeople from the Bronx

- American boxing trainers

- American boxers of Italian descent

- Deaths from pneumonia

- American male boxers

- Boxers from New York City

- People from Catskill, New York

- Infectious disease deaths in New York (state)