Cyprus–Turkey maritime zones dispute

The Republic of Cyprus (Cyprus) and Turkey have been engaged in a dispute over the extent of their exclusive economic zones (EEZ), ostensibly sparked by oil and gas exploration in the area. Turkey objects to Cypriot drilling in waters that Cyprus has asserted a claim to under international maritime law. The present maritime zones dispute touches on the perennial Cyprus and Aegean disputes; Turkey is the only member state of the United Nations that does not recognise Cyprus, and is one of the few not signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which Cyprus has signed and ratified.

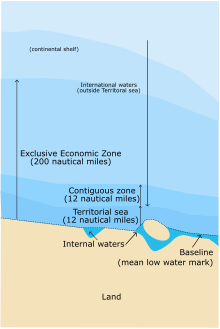

Turkey claims a portion of Cyprus's EEZ based on Turkey's definition that no islands, including Cyprus, can have a full 200 nautical mile EEZ [1][2] authorized to coastal states and should only be entitled to their 12 nautical mile territorial seas. Turkey's definition creates a dispute over the rights to waters south of Cyprus containing an offshore gas field. This definition is not shared by most other states.[3][4][5][6][7] Furthermore, the internationally unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which was created as result of the Turkish Invasion of Cyprus, also claims portions of Cypriot EEZ. Cyprus and other countries including Israel, France, Russia and Greece view these claims[8][9][10][11] on Cyprus's land and sea as illegal under international law[a] and urge Turkey to refrain from illegal drilling for gas in the island's EEZ.[b] The European Union has threatened Turkey with economic and political sanctions for violating the Cypriot EEZ.[28][29]

Since Turkey does not recognise the Republic of Cyprus, there are no diplomatic relations between the two states. The Republic of Cyprus has refused to negotiate the maritime dispute and natural resources found in Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ with the Turkish Cypriot leadership.[30]

Chronology[]

The first discoveries and agreements in the region[]

The first discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean were made between June 1999 and February 2000 offshore Israel. In 2003 Shell made the first significant discoveries of gas, offshore Egypt.[30]

In February 2003 an EEZ delineation agreement was signed between Republic of Cyprus and Egypt.[30] TRNC responded by stating that they do not recognise the agreement.[30]

In February 2004, after performing drillings in the area, Shell's Matthias Bichsel announced that ‘The drilling results have demonstrated that this ultra-deepwater area is a rich hydrocarbon province’.[30]

In April of the same year, in two separate referenda, the Annan Plan was rejected by the Greek Cypriots, while accepted by the Turkish Cypriots. Regarding the maritime dispute, the acceptance of the Annan Plan would mean that after the solution the natural resources would be under the authority of the bicommunal Presidential Council.[30] On May 1, Republic of Cyprus joined the European Union.

In January 2007 an EEZ delineation agreement was reached between Republic of Cyprus and Lebanon.[30] However, it has not been ratified by the Parliament of Lebanon yet. Some argue that the reason is a dispute between Lebanon and Israel over their maritime borders,[31] pressure from Turkey,[30] the relations between Turkey and Lebanon,[32] and a potential trade agreement between Lebanon and Turkey, which was eventually signed in 2010.[33]

First Licensing Round and growing interest in the region[]

In May, 2007, the Republic of Cyprus announced the 1st Licensing Round Offshore Cyprus, for Blocks 1, 2, 4-12, which received 3 bids.[30] In October, 2008, Noble Energy granted a Hydrocarbon Exploration Licence for Block 12.[34]

In November 2008, vessels performing research activities in the Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ under contract with the Republic of Cyprus were intercepted by vessels of the Turkish Navy, and were asked to leave, as they claimed that their activities were conducted in areas under Turkish jurisdiction.[35][36]

In January, 2009 the first big offshore discoveries were made in the Tamar 1, offshore Israel.[30] Later, in March, 2009, new discoveries were made offshore Israel, at the Dalit 1 site.[30]

In March, 2010, the US Geological Survey revealed that “the waters of the Levant Basin […] contain a mean of 122 tcf (3,455 bcm) of recoverable natural gas and 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable crude oil”, increasing the interest in the region.[30]

Break in the Turkish-Israeli relations and form of new alliances[]

On May 31 of 2010, the Mavi Marmara incident took place. In the Mavi Marmara or Flotilla incident, activists’ boats were blocked by Israeli forces in international waters, on their way to provide humanitarian assistance to Gaza. The Israeli soldiers were met with resistance while boarding the Mavi Marmara and opened fire, killing nine Turkish citizens. The incident resulted to the sudden end of all diplomatic relations between Turkey and Israel.[37][38]

The deterioration of Turkish-Israeli relations, which reached its peak with the Mavi Marmara incident; in connection to the discoveries made in the Leviathan field offshore Israel, the greatest discoveries of gas made until then in the region, in October, 2010[30] and the new geopolitical realities in the Eastern Mediterranean;[38] led to an “unprecedented political, military and energy cooperation” between Israel and Cyprus and Greece.[33][37][38] In December 2010, an EEZ agreement was signed between The Republic of Cyprus and Israel,[30] with Turkey reacting by questioning the Greek Cypriots’ willingness to achieve a solution to the Cypriot Problem, stating that they “ignor[e] Turkish Cypriots’rights”.[30]

First explorations, reaction of Turkey and TRNC, and Eroğlu’s proposal[]

During September, 2011, Noble initiated the first exploratory drilling for Republic of Cyprus, in Block 12,[30][35] with Turkey reacting by delineating their EEZ with TRNC.[30] Turkish Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan described the action as a ‘reciprocal decision’ to the actions of Republic of Cyprus.[30] During September, Turkish officials issued harsh warnings towards The Republic of Cyprus in several occasions.[30] On September 22 and 23 of 2011, TPAO received exploration licences from the TRNC, including areas overlapping with blocks licensed by The Republic of Cyprus, and Turkish vessel Piri Reis began seismographic research south of Cyprus and near Noble's platform, accompanied by Turkish warships.[30][35]

In September 2011, Turkish Cypriot leader Derviş Eroğlu submitted a proposal for mutual suspension of activities within the maritime space around Cyprus, or the cooperation between the two communities on hydrocarbons, on issues such as distribution of profits.[30] Republic of Cyprus rejected Eroğlu's proposal, responding that “exploration and exploitation of our natural resources constitutes a sovereign right of the Republic of Cyprus. [...] Our sovereign right is not negotiable”.[30]

In December 2011, Noble announced discoveries in Block 12, close to Israel's Leviathan.[30][35] The discovered gas field, ‘Aphrodite’, was declared ‘commercial’ in June 2015.[35]

Second Licensing Round and new proposal by Eroğlu[]

On February, 2012, Republic of Cyprus announced the 2nd Licensing Round, for 12 blocks, which received 15 bids.[30][35][39] Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in response stated that they would not allow activities in blocks 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, which Turkey also claims theirs, and would “take all necessary measures to protect its rights and interests in the maritime areas falling within its continental shelf”.[30]

On September 29, 2012, a new proposal was submitted by the Turkish Cypriot side but was again rejected by the Greek-Cypriot side. The proposal included a bicommunal technical committee for natural resources and related agreements and revenues, with a chairman appointed by the Secretary General of the UN, and a pipeline transporting hydrocarbons through Turkey.[30]

In January 2013, ENI-Kogas granted Hydrocarbon Exploration Licences for Blocks 2, 3 and 9, and on the following February Total granted Hydrocarbon Exploration Licences for Blocks 10, 11.[35][39]

Barbaros and NAVTEX in Cyprus waters[]

On February, 2013, TPAO finalized the purchase of 3D seismic vessel Polarcus Samur, which was renamed RV Barbaros Hayreddin Paşa.[40] Barbaros was used for explorations within Republic of Cyprus EEZ.[32] In October 2014, Barbaros entered Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ, accompanied by Turkish warships. President of Cyprus Nicos Anastasiades reacted by withdrawing from the bi-communal negotiation process for the Cypriot problem, in protest for Turkey's violation of Republic of Cyprus’ sovereign rights.[35][41]

In January 2015, Turkey issued a NAVTEX for the period between January and April, reserving areas in the Eastern Mediterranean that included parts of Republic of Cyprus's EEZ, while Barbaros conducted research in the region, in the presence of the Turkish navy.[35][41] Negotiations for the Cypriot Problem resumed after Turkey's NAVTEX expired, in May, 2015, with newly elected Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa Akinci.[35]

The Eastern Mediterranean Gas Pipeline[]

In May 2015, the European Commission grants €2 million to Eastern Mediterranean Gas Pipeline (EMGP), a proposed pipeline transferring gas from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe through Greece, for pre-FEED studies.[42] In January 2017, a study by Edison presented to the EU's Directorate-General for Energy described the project as ‘commercially viable and technically feasible’,[35] while in January 2018, the Commission granted the project another €34.5 million for the FEED study and other expenses.[42] In December 2018, a framework agreement regarding the project was signed between the governments of Israel, Republic of Cyprus, Greece and Italy.[35]

Zohr and Third Licensing Round[]

In August, 2015, the biggest to-date discovery in the Eastern Mediterranean was made, within the EEZ of Egypt, in the Zohr gas field, by ENI. Zohr was found six kilometres away from Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ.[43]

In February, 2016, the 3rd licensing round for Republic of Cyprus was announced, for Blocks 6, 8 and 10.[43][35]

Turkey’s new NAVTEX and drillings[]

In March, 2017, Turkey announced their intention to proceed to exploration drillings in areas delimited by the Republic of Cyprus.[43] In April, 2017, Turkey released a NAVTEX for maritime areas east of Cyprus, overlapping with the EEZ of the Republic of Cyprus, for Barbaros to perform seismic surveys between April and June,[35] with Republic of Cyprus again protesting for Turkey's violation of its sovereignty and sovereign rights.[44]

ENI’s discoveries and increasing tensions[]

In April 2017, ENI was granted Block 8, ENI/TOTAL granted Block 6, and Block 10 was given to a cooperative bid of Exxon and Qatar Petroleum.[42] On February 8, 2018, ENI announced discoveries of lean gas within Republic of Cyprus's EEZ, in well ‘Calypso 1’ of Block 6, which is also claimed by Turkey.[43][45]

Three days later, on February 11, 2018, ENI's drill ship was blocked by the Turkish navy on its way to perform drillings within Republic of Cyprus's EEZ, in Block 3, and the drilling was prevented, with the ship returning to the port two weeks later.[43][35] The incident has been described as “the first (and only one until now) serious incident of military activity of this kind since the beginning of the Cypriot exploratory programme”.[43]

In November 2018, Exxon Mobil started exploratory drillings in Block 10, in the Delphyne-1 well.[43][35]

Barbaros seismic surveys, new discoveries, and Fatih’s drilling in Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ[]

In January 2019, Barbaros began a new round of seismic surveys within the EEZ of Republic of Cyprus, while the Turkish navy released a NAVTEX for military exercises within Blocks 7 and 8.[35]

On February 28, 2019, ExxonMobil announced the largest to-date discoveries within the EEZ of Republic of Cyprus, at Glaucus-1, within Block 10.[35]

In early May 2019, Turkish drilling ship Fatih 1 arrived west of Cyprus, in order to perform drillings,[46] with Republic of Cyprus reacting by issuing arrest warrants for the staff of Fatih and accompanying ships.[47]

On June 16, 2019, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu stated that Fatih began performing drillings, while also announcing the arrival of a second drilling ship in the region.[48] Four days later, on June 20, Turkish drilling ship Yavuz began drillings northeast Cyprus, as announced earlier by Turkish officials.[49][50] Republic of Cyprus and Greece reacted by pushing for EU's reaction to Turkey's actions.[49] As a result, on 16 of July 2019, the EU suspended funding of $163 million towards Turkey, as a reaction to Turkey's activities within the EEZ of Republic of Cyprus.[51]

Meanwhile, on July 13, Turkish Cypriot leader Mustafa Akinci submitted a new proposal for a joint committee on hydrocarbons consisting of members from both communities, receiving the support of the Turkish government.[52][53] Akinci's proposal was rejected by president of Cyprus Nicos Anastiasiades, after a meeting with the leaders of Greek-Cypriot political parties.[54]

EU Position[]

In November 2019, European Union foreign ministers have approved a mechanism to sanction entities involved in unauthorized oil drilling in Cypriot waters.[55] The sanctions would involve travel bans and asset freezes on people, companies and organizations. EU citizens and firms will not be allowed to provide any funds or technical support to Turkey for the drilling operations.[56]

US Position[]

The US respects the rights of Cyprus to develop its resources and has repeated caution to Turkeys destabilizing Oil & Gas research within Cyprus EEZ.[57][58] The "US remains deeply concerned by Turkey’s repeated attempts to conduct drilling operations in the waters off Cyprus... This provocative step raises tensions in the region. We urge Turkish authorities to halt these operations and encourage all parties to act with restraint and refrain from actions that increase tensions in the region" stated Morgan Ortagus of the United States Department of State in 2019.[59][60][61]

Republic of Cyprus' perspective[]

The Republic of Cyprus adopted the Territorial Sea Law in 1964. The law established 12-nautical-mile (22 km; 14 mi) territorial sea. Coordinates of the territorial sea were submitted to the United Nations in 1993 and their validity was reconfirmed in 1996.[30] The continental shelf of Cyprus is defined according to the Continental Shelf Law which was adopted in 1974. After ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1988, Cyprus adopted a new law in 2004, which limited its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) by 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi). The EEZ was delimited by bilateral agreements with Israel, Lebanon and Egypt.[30] Cyprus has called on Turkey to delineate the sea boundaries between the two countries.[62][63][64][65]

The area of highest interest to Cyprus is Block 12, approximately 800,000 acres (3,200 km2) in size, and on the border with Israel's own EEZ. Cyprus has actively sought to reinforce its position on the global stage through congress with major international players in the situation. Cypriot Foreign Minister Erato Kozakou-Marcoullis began her term in office in late 2011 by visiting both Greece and Israel to request support for the drilling program,[66] though it is not clear if military support was also requested. It is also widely believed that Cyprus has requested support from the United States of America and the Russian Federation, though the exact specifics of any representations have not been made public.

As of August 2011, the Cypriot media has shown widespread alarm at Turkish threats to intervene against the drilling program, and has remonstrated with the Turkish position as evidence of a violation of national sovereignty and the rights of the Cypriot people. In late February 2014, Cypriot president Nicos Anastasiades threatened to pull out of the new round of negotiations over the Cyprus dispute if Turkish vessels continue to intrude in Cyprus' exclusive economic zone.[67]

Turkish and Turkish Cypriot perspective[]

Turkey is not a party to UNCLOS, mainly due to the Aegean dispute with Greece and due to provisions of the article 121 of UNCLOS which states that maritime zones of islands (except uninhabited rocks) are determined by the same principles as for the other territories.[30][68] It has limited its territorial waters by 6 nautical miles (11 km; 6.9 mi) and by 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) in the Mediterranean Sea, established by the Council of Ministers of Turkey. There is no national legislation on EEZ or continental shelf. No EEZ proclamation exists for the Mediterranean Sea; however, it has signed an agreement in 2011 with the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus to delimit continental shelf.[30]

Turkey does not recognize Cyprus' EEZ agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, and Israel due to the position that as a de facto divided island Republic of Cyprus cannot represent the interests of Northern Cyprus in the case the island will be reunified with a single EEZ.[68] Turkey has disputed the EEZ agreement between Cyprus and Egypt based on its claims to the part of the continental shelf in that area.[30] These claims are based on the viewpoint that the capacity of islands to generate maritime zones should be limited in competition with the continental coastal states.[30] As a result, Turkey's claims are partly overlapping with Cyprus' EEZ blocks 1, 4, 6, and 7.[68] Turkey also supports Northern Cyprus' claims in blocks 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 12, and 13, including seabed within a few kilometers of the Aphrodite gas field. In addition to the blocks contested between Northern Cyprus and Turkey, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus has issued exploration licenses also in above-mentioned disputed blocks.[68] Turkish oil company TPAO has also begun conducting oil and gas exploratory drilling off the shores of Northern Cyprus.[68][69]

The European Union (EU) acquis communautaire requires UNCLOS membership.[70] The European Parliament called on Turkey to sign UNCLOS in adopting the Commission's annual report on paving the ground for EU–Turkey accession negotiations in 2012, 2013 and 2014.[70][71][72]

Turkey has repeatedly threatened to not allow the Republic of Cyprus to proceed with pursuing claims to hydrocarbon deposits in waters south of the island. It has warned international oil companies not to conduct exploration and production activities in disputed zones, under the threat of an exclusion from the business operations in Turkey.[68] It is not clear whether the incident could escalate to violence, as the Turkish Government has not made clear whether it regards oil and gas exploration by the Republic of Cyprus as an act of aggression.

However, in November 2008, Turkish naval vessels harassed Cyprus contracted vessels conducting seismic exploration for hydrocarbon deposits in waters south of the island.[73]

Blue Homeland[]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Needs integration with the rest of the article, following the merger of the Blue Homeland artice. (January 2021) |

The Blue Homeland (Turkish: Mavi Vatan), is an irredentist and expansionist concept and doctrine,[c] created by the Chief of Staff of the Turkish Navy Commander Cihat Yaycı, and developed with Admiral Cem Gurdeniz in 2006.[82][83][84][75] The doctrine is representing Turkey's territorial sea, continental shelf, and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the Black Sea, as well as its claims of continental shelf and EEZ in the eastern Mediterranean, and the Aegean.[85]

- History

On 2 September 2019, Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan appeared in a photograph with a map that depicted nearly half of the Aegean Sea and an area up to the eastern coast of Crete as belonging to Turkey. The map was displayed during an official ceremony at the National Defense University of Turkey in Istanbul[86] and shows an area labelled as "Turkey's Blue Homeland" stretching up to the median line of the Aegean,[87] enclosing the Greek islands in that part of the sea without any indication of the Greek territorial waters around them.

On 13 November 2019, Turkey submitted to the United Nations a series of claims to Exclusive Economic Zones in the Eastern Mediterranean that are in conflict with Greek claims to the same areas – including a sea zone extending west of the southeastern Aegean island of Rhodes and south of Crete. The Turkish claims were made in an official letter by Turkey's Permanent Representative to the UN Feridun Sinirlioglu, which reflect Ankara's notion of a "Blue Homeland" (Mavi Vatan). Greece condemned these claims as legally unfounded, incorrect and arbitrary, and an outright violation of Greece's sovereignty.[88]

- Turkey's view

Turkey's position, unlike most other relevant states,[89][90][91][92][93][94] is that islands cannot have a full Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)[95][96] and should only be entitled to a 12 nautical mile reduced EEZ or no EEZ at all, rather than the usual 200 miles that Turkey and every other country are entitled to according to Article 121 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Turkey has not ratified UNCLOS, and argues that it is not bound by its provisions that award islands maritime zones. In this context, Turkey, for the first time on December 1, 2019, claimed that the Greek island of Kastellorizo shouldn't have any EEZ at all, because, from the equity-based[97][98] Turkish viewpoint, it is a small island immediately across the Turkish mainland (which, according to Turkey, has the longest coastline), and isn't supposed to generate a maritime jurisdiction area four thousand times larger than its own surface. Furthermore, according to Turkey's Foreign Ministry, an EEZ has to be coextensive with the continental shelf, based on the relative lengths of adjacent coastlines[94] and described any opposing views supporting the right of islands to their EEZ as "maximalist and uncompromising Greek and Greek Cypriot claims".[98][97][99] On 20 January 2020, the Turkish President Erdogan challenged even the rights of Crete, Greece's largest island and 5th largest in the Mediterranean, stating that "They talk about a continental shelf around Crete. There is no continental shelf around the islands, there is no such thing, there, it is only sovereign waters."[100]

- International Community's views

The Ambassadors of the United States and Russia to Athens, Geoffrey Pyatt and respectively, while commenting on Turkey's view, stated that all the islands have the same rights to EEZ and continental shelf as the mainland does.[101][102][103] The then US Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, Aaron Wess Mitchell, criticized the Turkish view, stating that it "is a minority of one versus the rest of the world."[104]

6 nautical miles: Current territorial sea limits as recognized by Greece and Turkey in the Aegean.

12 nautical miles: Upper limit of territorial sea limits defined as a legal right by UNCLOS; possible future claims by Greece and Turkey in the Aegean.

Conflicting claims to continental shelf and EEZ areas in the eastern Mediterranean. Blue: areas claimed by Greece and Cyprus; red: areas claimed by Turkey.

Potential for escalation to armed conflict[]

Turkey organised a major air and naval exercise at the same time as drilling by Cypriot contractors was to begin in September 2011.[73]

The Russian Navy in late August 2011 scrambled two nuclear attack submarines to the Eastern Mediterranean to observe the situation,[105] as Cyprus and Russia have enjoyed close political and economic ties recently.[106]

In 2011, Israel has increased the number of surveillance flights in the Eastern Mediterranean,[107][108] though it is not clear if these operations include the Nicosia Flight Information Region.

Views in the academic literature[]

On the dispute[]

Writing in 2018, Michalis Kontos and George Bitsis argue that, despite great asymmetry of power, Turkey will not reach their objective to have relative gains and “revise the status quo offshore Cyprus”, due to the involvement of big oil and gas companies in Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ. Moreover, they argue that Turkey's actions are not compatible with Alexander L. George's notion of ‘coercive diplomacy’, neither are Republic of Cyprus’ actions compatible with George's notion of deterrence, as neither's actions involve the use of military force.[43]

On the approaches[]

Kontos and Bitsis argue that there has been a shift in Turkey's approach on the issue after 2011, from military threats to questioning the sovereign rights of Republic of Cyprus over their EEZ and proceeding with their own explorations in the region, only to shift back to military threats in February, 2018.[43]

Meanwhile, Ayla Gürel, Fiona Mullen and Harry Tzimitras also note a shift on the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot approach, from protesting and warning to block Republic of Cyprus’ activities, to taking reciprocal actions as a reaction to Republic of Cyprus’ unilateral actions.[30]

Prospects for peace and conflict[]

Peace[]

Many academics recognise that discoveries of gas in the region can serve as an economic incentive to resolve long-lasting conflicts, including the Cyprus problem, and form a new energy cooperation.[32][109]

Vedat Yorucu and Özay Mehmet argue that regional geopolitical developments and economic conditions in Cyprus have made the solution to the Cyprus problem more urgent. A solution to the Cyprus problem, and the consequent EEZ dispute would be a win-win scenario for all parties involved, and transform Cyprus to an energy sub-hub, if connected to Ceyhan, Turkey.[32]

Others, however, argue that geopolitical realities don't favour peace and regional cooperation between the actors involved, including Turkey, Greece and Cyprus.[33]

Conflict[]

Academics also recognise the possibility that recent gas discoveries in the region can exacerbate existing conflicts.[32][109]

According to Andreas Stergiou, the actions of Eastern Mediterranean states in regard to their energy projects show that states prioritize security concerns over economic. The discoveries made in the region have only exacerbated existing conflicts and made reconciliation even more improbable.[33]

Cyprus Gas, European Energy security and exploitation options[]

European Energy Security[]

Writing in 2012, ELIAMEP's Thanos Dokos noted that the need for oil and gas for Europe would be a motive for NATO and the EU to actively secure their supply through operations in the Eastern Mediterranean, highlighting the region's importance for European energy and economic security.[110]

Writing in 2018, Theodoros Tsakiris argued that the discoveries made in the Eastern Mediterranean, including those within Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ, could help EU's efforts to diversify their gas supply, in order to decrease their dependency on Russian gas, which limits the EU's energy security and the capacity to act politically and economically against Russia. If transferred as LNG or through the EMGP, EU could also avoid a future overdependence on Turkey's Trans Anatolian pipeline.[42]

Exploitation options[]

According to Tsakiris, despite the interest shown by Italy, Greece, Republic of Cyprus, Israel and EU, the profitability of the EMGP project is debatable due to various reasons, such as the pipeline's length and depth, and limited findings of gas in Republic of Cyprus’ EEZ. Tsakiris argues that the use of Egypt's LNG facilities would be the only realistic option, currently.[42]

Vedat Yorucu and Özay Mehmet argue that Cyprus LNG would not be competitive in the gas market and that the EMGP might present technical difficulties. Instead, they argue that a pipeline between Israel, Cyprus and Turkey would be the most economically beneficial option, acknowledging, however, its improbability due to the Cyprus problem.[32]

See also[]

- 2018 Cyprus gas dispute

- Cyprus dispute

- Northern Cyprus

- Neo-Ottomanism

- Exclusive economic zone of Greece

- Aegean dispute

- Libya (GNA)–Turkey maritime deal

References[]

- ^ "Turkey sends non paper to EU, warning to stay away from Cyprus EEZ". KeepTalkingGreece. 23 June 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "Greece's maritime claims 'maximalist,' violate international boundaries law". Daily Sabah. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "Im östlichen Mittelmeer sollen Erdgasvorkommen von mehreren Billionen Kubikmetern liegen. Das befeuert den Zypernkonflikt". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "NZZ: Boreholes rekindle the Cyprus problem (original: ΝΖΖ: Οι γεωτρήσεις αναζωπυρώνουν το Κυπριακό)". Kathimerini. 13 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Cypriot EEZ and Kastellorizo - Erdogan's geostrategic stakes (Original: "Κυπριακή ΑΟΖ και Καστελλόριζο - Το γεωστρατηγικό διακύβευμα του Ερντογάν"". SLPress. 4 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Turkey-Libya maritime agreement draws Greek ire". ArabNews. 30 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

Last year, Wess Mitchell, US assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, sent a message to Ankara over the drilling activities for hydrocarbons underway in Cyprus’s exclusive economic zone. He said that “Turkey’s view is a minority of one versus the rest of the world.”

- ^ "US official sends clear message to Turkey over Cyprus drilling". Kathimerini. 16 December 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

Turkey’s view “is a minority of one versus the rest of the world,” he said. “The rest of the world has a very clear, straightforward view that the exclusive economic zone of Cyprus is grounded in international law.”

- ^ "Wess Mitchell sends clear message to Turkey over Cyprus". Kathimerini. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ "Gas Partnership: Netanyahu Visits Cyprus". Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Makris, A. "Cyprus Calls on Turkey to Steer Away From Threats – GreekReporter.com". Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ "Athens, Paris, Moscow and Cairo urge Ankara not to violate Cyprus' sovereignty". Kathimerini. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ European Consortium for Church-State Research. Conference (2007). Churches and Other Religious Organisations as Legal Persons: Proceedings of the 17th Meeting of the European Consortium for Church and State Research, Höör (Sweden), 17–20 November 2005. Peeters Publishers. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-429-1858-0.

There is little data concerning recognition of the 'legal status' of religions in the occupied territories, since any acts of the 'Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus' are not recognized by either the Republic of Cyprus or the international community.

- ^ Quigley (2010-09-06). The Statehood of Palestine. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-139-49124-2.

The international community found this declaration invalid, on the ground that Turkey had occupied territory belonging to Cyprus and that the putative state was therefore an infringement on Cypriot sovereignty.

- ^ Nathalie Tocci (January 2004). EU Accession Dynamics and Conflict Resolution: Catalysing Peace Or Consolidating Partition in Cyprus?. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7546-4310-4.

The occupied territory included 70 percent of the island's economic potential with over 50 percent of the industrial ... In addition, since partition Turkey encouraged mainland immigration to northern Cyprus. ... The international community, excluding Turkey, condemned the unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) as a.

- ^ Dr Anders Wivel; Robert Steinmetz (28 March 2013). Small States in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4094-9958-9.

To this day, it remains unrecognised by the international community, except by Turkey

- ^ Peter Neville (22 March 2013). Historical Dictionary of British Foreign Policy. Scarecrow Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8108-7371-1.

...Ecevit ordered the army to occupy the Turkish area on 20 July 1974. It became the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, but Britain, like the rest of the international community, except Turkey, refused to extend diplomatic recognition to the enclave. British efforts to secure Turkey's removal from its surrogate territory after 1974 failed.

- ^ "U.S. and EU concerned by Turkey's plans to drill off Cyprus". Reuters. 2019-05-06. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Southern EU leaders express support for Cyprus amid Turkish energy ambitions". Kathimerini. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "EPP Group urges prompt EU answer to Turkish actions in Cyprus". eppgroup.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "France Urges Turkey to Halt 'Illegal Activities' in Cyprus". aawsat.com. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "France sends strict warning to Turkey on Cyprus EEZ- EP President also expresses support". balkaneu.com. 2019-05-06. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "US urges Turkey against drilling off Cyprus". france24.com. 2019-05-06. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Armenia urges Turkey to cease all activities within Cyprus EEZ". panorama.am. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Israel backs Cyprus as Turkey vows to continue drilling in its waters". Times of Israel. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Israel gives Cyprus 'full support' in gas drilling dispute with Turkey". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "EEZ: Switzerland's Foreign Minister on Cyprus's side: (original: "ΑΟΖ: Στο πλευρό της Κύπρου και ο Ελβετός ΥΠΕΞ")". onalert.gr. 2019-07-10. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: 'We support our ally Cyprus against Turkey's activities in Mediterranean'". Middle East Monitor. 13 September 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "EU leaders blast Turkey over Cyprus' EEZ, order list of sanctions". tovima.gr. 2019-06-21. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Turkey's East Med ambitions facing EU roadblock – Bloomberg". ahvalnews.com. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Gürel, Ayla; Mullen, Fiona; Tzimitras, Harry (2013). The Cyprus Hydrocarbons Issue: Context, Positions and Future Scenarios (PDF). PCC Report. Peace Research Institute Oslo. pp. 1–64. ISBN 9788272884863.

- ^ Bilgin, Mert (2019), "Prospects of Natural Gas in Turkey and Israel", Contemporary Israeli–Turkish Relations in Comparative Perspective, Springer International Publishing, pp. 195–215, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05786-2_8, ISBN 9783030057855

- ^ a b c d e f Yorucu, Vedat; Mehmet, Özay (2018). The Southern Energy Corridor: Turkey's Role in European Energy Security. Lecture Notes in Energy. Vol. 60. Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-63636-8. ISBN 978-3-319-63635-1.

- ^ a b c d Stergiou, Andreas (2017). "Energy security in the Eastern Mediterranean". International Journal of Global Energy Issues. 40 (5): 320. doi:10.1504/ijgei.2017.10008015. ISSN 0954-7118.

- ^ Republic of Cyprus. "1st Licensing Round". www.mcit.gov.cy. Retrieved 2019-07-24.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Hazou, Elias (2016). "Drilling for Cyprus gas, a timeline". Cyprus Mail.

- ^ İnan, Yüksel; Ercan, Pınar Gözen (2017), "Maritime Relations of Peninsular Turkey: Surrounded by Hostile or Peaceful Waters?", Turkish Foreign Policy, Springer International Publishing, pp. 281–301, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50451-3_14, ISBN 9783319504506

- ^ a b Almog, Orna; Sever, Ayşegül (2019), "The Mavi Marmara: An Embattled Voyage and Its Consequences", Contemporary Israeli–Turkish Relations in Comparative Perspective, Springer International Publishing, pp. 61–100, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05786-2_4, ISBN 9783030057855

- ^ a b c Ersoy, Tuğçe (2019), "Emerging Alliances, Deteriorating Relations: Turkey, Israel and Greece in the Eastern Mediterranean", Contemporary Israeli–Turkish Relations in Comparative Perspective, Springer International Publishing, pp. 101–137, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05786-2_5, ISBN 9783030057855

- ^ a b Republic of Cyprus. "2nd Licensing Round". www.mcit.gov.cy. Retrieved 2019-07-24.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Polarcus (11 February 2013). "Polarcus completes sale of Polarcus Samur". www.polarcus.com. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ a b Skordas, Aggelos (2 April 2015). "Turkish Research Vessel 'Barbaros' Leaves Cyprus' EEZ". Greek Reporter. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Tsakiris, Theodoros (2018). "The Importance of East Mediterranean Gas for EU Energy Security: The Role of Cyprus, Israel and Egypt". The Cyprus Review. , 30(1): 23–48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kontos, Michalis; Bitsis, George (2018). "Power Games in the Exclusive Economic Zone of the Republic of Cyprus: The Trouble with Turkey's Coercive Diplomacy". The Cyprus Review. 30 (1): 51–70.

- ^ Republic of Cyprus (19 April 2017). "Press release by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the NAVTEX issued by Turkey on 19/04/2017". www.mfa.gov.cy. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ ENI (2018-02-08). "Eni announces a gas discovery Offshore Cyprus". www.eni.com. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ "Greece, Cyprus pressure EU to act over Turkey gas drilling as..." Reuters. 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ "Fatih arrest warrants paying off, sources say". ekathimerini.com. 15 June 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ "Turkish FM says Fatih has started drilling 'west of Cyprus'". ekathimerini.com. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ a b "Turkey sends second ship to drill near Cyprus, EU warns of action". Reuters. 2019-06-20. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ Smith, Helena (2019-06-18). "Greece and Cyprus call on EU to punish Turkey in drilling dispute". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ Stevis-Gridneff, Matina (2019-07-15). "E.U. Punishes Turkey for Gas Drilling Off Cyprus Coast". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ Christou, Jean (2019-07-13). "Akinci submits gas cooperation proposal through UN (Update 3)". Cyprus Mail. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ Republic of Turkey. "No: 203, 13 July 2019, Press Release Regarding The New Cooperation Proposal of TRNC on Hydrocarbon Resources". Republic of Turkey's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ Christou, Jean (2019-07-16). "Party leaders reject Akinci proposal in joint statement (update 3)". Cyprus Mail. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- ^ Christou. "EU targets Turkey's oil drilling off Cyprus coast". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "EU Unveils Sanctions Plan to Hit Turkey Over Cyprus Drilling". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-11-12.

- ^ "The Race for Natural Gas: Will the Eastern Mediterranean Become a World Center for the Natural Gas?". Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ "US Worry Grows Over Turkey's Drilling Plan Off Cyprus". 2019-06-07. Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ "U.S. Embassy in Cyprus: Statement on Turkish Drilling in Cypriot Claimed Waters". 2019-07-10. Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- ^ "US cautions Turkey over Cyprus". Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- ^ "U.S. tightens links with Cyprus, warns Turkey over EEZ infractions". Retrieved 2019-08-10.

- ^ "U.S. Embassy in Cyprus: Ambassador Garber's Interview with Thanasis Athanasiou, published in Alithia". 2019-07-29. Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ "Cyprus gas discoveries spark US-Russian gamesmanship". Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ "Turkey's Big Energy Grab". Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ "EU draws up measures against Turkey over Cyprus drilling". 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2019-08-22.

- ^ Evripidou, Stefanos (August 26, 2011). "Marcoullis; we got the support we needed and are very satisfied". Cyprus Mail Report. Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ "Negotiations will end if Turkey violates South's EEZ: Anastasiades". LGC news. Lemon Grove Cyprus. 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- ^ a b c d e f Emerson, Michael (2013). "Fishing for Gas and More in Cypriot Waters" (PDF). Insight Turkey. SETA. 15 (1): 165–181. ISSN 1302-177X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-09. Retrieved 2014-03-09.

- ^ Hadjicostis, Menelaos (2012-04-26). "Turkey starts oil, gas search in north Cyprus". Associated Press. Retrieved 2014-03-10.

- ^ a b Gültaşli, Selçuk (2012-01-06). "European Parliament tells EU to cooperate against terrorist PKK". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

- ^ "EP resolution calls for the withdrawal of occupation troops from Cyprus". Famagusta Gazette. 2013-04-19. Archived from the original on 2013-04-30. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

- ^ "Ευρωβουλή: Ψήφισμα για όλα τα γούστα". Ο Φιλελεύθερος. 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2014-03-17.

- ^ a b Evripidou, Stefanos (August 24, 2011). "As drilling looms, Wikileaks reveals previous tensions". Cyprus Mail Report. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ "How two 16th-century pirates inspired Erdogan's foreign policy". David Lepeska. The National News. 14 October 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Turkish admiral's resignation exposes a new showdown in Ankara". Yavuz Baydar. Ahval News. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Turkish presidency releases video promoting Blue Homeland doctrine". Kathimerini. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "Biden and Erdogan: Five Potential Flashpoints in US-Turkish Relations". Aykan Erdemir. Balkan Insight. 19 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "How Erodgan-led Turkey went from NATO ally to liability". David Romano. Arab News. 4 September 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Turkey-Greece tensions: Mediterranean waters roiled by Blue Homeland doctine". Washington Post. 27 September 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Turkey's unfinished war with the West". Simon Schofield. Jerusalem Post. 1 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Nicolas Baverez: "Il faut arrêter Recep Tayyip Erdogan!"". Le Figaro. 1 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Fatih again in the Cypriot EEZ". BalkanEU. 15 November 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Turkey: Erdogan dismisses the "father of the Blue Homeland"". BalkanEU. 16 May 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Blue Homeland: the doctrine behind Turkey's Mediterranean claims". Andrew Wilks. The National News. 14 August 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Aydınlık". 2020-12-04. Archived from the original on 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- ^ "Erdogan takes photograph in front of 'Blue Homeland' map". Kathimerini. 2 September 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ Mariano Giustino, Dentro la dottrina marittima turca della Mavi Vatan che accende lo scontro con la Grecia, huffingtonpost, 26/08/2020.

- ^ "Turkey eyeing area west of Rhodes". Kathimerini. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ "Im östlichen Mittelmeer sollen Erdgasvorkommen von mehreren Billionen Kubikmetern liegen. Das befeuert den Zypernkonflikt". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "NZZ: Boreholes rekindle the Cyprus problem (original: ΝΖΖ: Οι γεωτρήσεις αναζωπυρώνουν το Κυπριακό)". Kathimerini. 13 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Cypriot EEZ and Kastellorizo - Erdogan's geostrategic stakes (Original: "Κυπριακή ΑΟΖ και Καστελλόριζο - Το γεωστρατηγικό διακύβευμα του Ερντογάν"". SLPress. 4 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Turkey-Libya maritime agreement draws Greek ire". ArabNews. 30 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

Last year, Wess Mitchell, US assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, sent a message to Ankara over the drilling activities for hydrocarbons underway in Cyprus's exclusive economic zone. He said that "Turkey's view is a minority of one versus the rest of the world."

- ^ "US official sends clear message to Turkey over Cyprus drilling". Kathimerini. 16 December 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

Turkey's view "is a minority of one versus the rest of the world," he said. "The rest of the world has a very clear, straightforward view that the exclusive economic zone of Cyprus is grounded in international law."

- ^ a b "Turkey, Libya delimitation deal raises geopolitical tensions". New Europe. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

Turkey defines its 'EEZ' to be coextensive with its continental shelf, based the relative lengths of adjacent coastlines, which completely disadvantages islands. It is a 'unique' interpretation not shared by any other country and not in accordance to the United Nations UNCLOS treaty, ratified by 167 countries but not Turkey,"

- ^ "Turkey sends non-paper to EU, warning to stay away from Cyprus EEZ". KeepTalkingGreece. 23 June 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "Greece's maritime claims 'maximalist,' violate international boundaries law". Daily Sabah. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ a b "QA-73, 1 December 2019, Statement of the Spokesperson of the Ministry of the Foreign Affairs, Mr. Hami Aksoy, in Response to a Question Regarding the Statements Made by Greece and Egypt on the Agreement Signed With Libya on the Maritime Jurisdiction Areas". Ministry of the Foreign Affairs of Turkey. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Turkey defends maritime deal with Libya". Kathimerini. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "New provocation by Turkey: disputes openly the continental shelf in Kastellorizo (original: Νέα πρόκληση της Τουρκίας: Αμφισβητεί ανοιχτά την υφαλοκρηπίδα στο Καστελόριζο)". in.gr. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ "Erdogan claims that Crete, islands have no continental shelf". Kathimerini. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "US envoy: Islands are entitled to EEZ, continental shelf". Kathimerini. 8 February 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Geoffrey Pyatt: All Greek islands have EEZ". Ethnos. 20 February 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Russian Ambassador to Athens: The islands have continental shelf and EEZ (Original: Ρώσος πρέσβης στην Αθήνα: Τα νησιά έχουν υφαλοκρηπίδα και ΑΟΖ)". CNN. 14 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Wess Mitchell sends clear message to Turkey over Cyprus". Kathimerini. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Fenwick, Sarah (2011-08-25). "Russia Sends Nuclear Subs To Patrol Cyprus Waters". Cyprus News Report. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ^ Barnes, Taylor (2010-07-01). "Russian spy ring paymaster disappears from Cyprus". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ^ NPR[dead link]

- ^ "Cyprus and Turkey – Oil Troubles". Cyprus Echo. December 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ a b Cohen, Erez (2018). "Development of Israel's natural gas resources: Political, security, and economic dimensions". Resources Policy. 57: 137–146. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.02.011. ISSN 0301-4207.

- ^ Dokos, Thanos (2012-11-26). "The evolving security environment in the eastern Mediterranean: is NATO still a relevant actor?". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 12 (4): 575–590. doi:10.1080/14683857.2012.744160. ISSN 1468-3857.

Further reading[]

- Wählisch, Martin (2011-12-05). "Israel-Lebanon Offshore Oil & Gas Dispute – Rules of International Maritime Law". ASIL Insights. 15 (3).

- Cyprus–Turkey relations

- Disputed waters

- Natural gas field disputes

- 2010s in Cyprus

- 2010s in Northern Cyprus

- 2010s in Turkey

- 2010s in Greece

- Cyprus dispute