Cyril of Alexandria

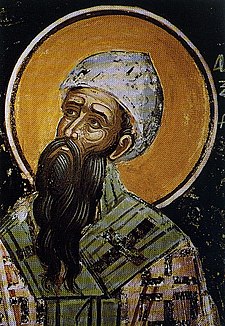

Saint Cyril of Alexandria | |

|---|---|

St Cyril of Alexandria, Patriarch, and Confessor | |

| Archdiocese | Alexandria |

| See | Alexandria |

| Predecessor | St. Theophilus of Alexandria |

| Successor | Dioscorus the Great "The Champion of Orthodoxy" |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 376 Didouseya, Roman Egypt (modern-day El-Mahalla El-Kubra) |

| Died | 444 (aged 67–68) Alexandria |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 18 January and 9 June (Eastern Orthodox Church) 27 June (Coptic Church, Catholic Church, Lutheranism) 9 February (Western Rite Orthodox Church, formerly Catholic Church, 1882–1969) 28 June (Church of England) |

| Venerated in | Latin Christianity Eastern Catholicism Eastern Orthodoxy Oriental Orthodoxy Anglicanism Lutheranism |

| Title as Saint | The Pillar of Faith; Seal of all the Fathers; Bishop, Confessor, Bishop of Alexandria, Teacher of the Faithand and also (in the Catholic Church) Doctor of the Church |

| Attributes | Vested as a Bishop with phelonion and omophorion, and usually with his head covered in the manner of Egyptian monastics (sometimes the head covering has a polystavrion pattern), he usually is depicted holding a Gospel Book or a scroll, with his right hand raised in blessing. |

| Patronage | Alexandria |

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

| Ethics |

|

| Schools |

|

| Philosophers |

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Oriental Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

| Oriental Orthodox churches |

|

|

|

Cyril of Alexandria (Ancient Greek: Κύριλλος Ἀλεξανδρείας; Coptic: Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ Ⲕⲩⲣⲓⲗⲗⲟⲩ ⲁ̅ also ⲡⲓ̀ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲕⲓⲣⲓⲗⲗⲟⲥ; c. 376 – 444) was the Patriarch of Alexandria from 412 to 444.[1][2] He was enthroned when the city was at the height of its influence and power within the Roman Empire. Cyril wrote extensively and was a leading protagonist in the Christological controversies of the late-4th and 5th centuries. He was a central figure in the Council of Ephesus in 431, which led to the deposition of Nestorius as Patriarch of Constantinople. Cyril is counted among the Church Fathers and also as a Doctor of the Church, and his reputation within the Christian world has resulted in his titles Pillar of Faith and Seal of all the Fathers. The Roman Emperor Theodosius II, however, condemned him for behaving like a "proud pharaoh", and the Nestorian bishops at their synod at the Council of Ephesus declared him a heretic, labelling him as a "monster, born and educated for the destruction of the church."[3]

Cyril is well known for his dispute with Nestorius and his supporter, Patriarch John of Antioch, whom Cyril excluded from the Council of Ephesus for arriving late. He is also known for his expulsion of Novatians and Jews from Alexandria and for inflaming tensions that led to the murder of the Hellenistic philosopher Hypatia by a Christian mob. Historians disagree over the extent of his responsibility in this.

Cyril tried to oblige the pious Christian emperor Theodosius II (AD 408–450) to himself by dedicating his Paschal table to him.[4] It is also important to note that Cyril's Paschal table was provided with a Metonic basic structure in the form of a Metonic 19-year lunar cycle adopted by him around AD 425, which was very different from the first Metonic 19-year lunar cycle invented around AD 260 by Anatolius, but exactly equal to the similar lunar cycle which had been introduced around AD 412 by Annianus; the Julian equivalent of this Alexandrian lunar cycle adopted by Cyril and nowadays referred to as the 'classical (Alexandrian) 19-year lunar cycle' would only much later emerge again: a century later in Rome as the basic structure of Dionysius Exiguus’ Paschal table (AD 525) and two more centuries later in England as the one of Beda's Easter table (AD 725).[5]

The Catholic Church did not commemorate Saint Cyril in the Tridentine Calendar: it added his feast only in 1882, assigning to it the date of 9 February. This date is used by the Western Rite Orthodox Church. Yet the 1969 Catholic Calendar revision moved it to 27 June, considered to be the day of the saint's death, as celebrated by the Coptic Orthodox Church.[6] The same date has been chosen for the Lutheran calendar. The Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches celebrate his feast day on 9 June and also, together with Pope Athanasius I of Alexandria, on 18 January.

Cyril is remembered in the Church of England with a commemoration on 28 June.[7]

Early life[]

Little is known for certain of Cyril's early life. He was born circa 376, in the town of Didouseya, Egypt, modern-day El-Mahalla El-Kubra.[8] A few years after his birth, his maternal uncle Theophilus rose to the powerful position of Patriarch of Alexandria.[9] His mother remained close to her brother and under his guidance, Cyril was well educated. His writings show his knowledge of Christian writers of his day, including Eusebius, Origen, Didymus the Blind, and writers of the Church of Alexandria. He received the formal Christian education standard for his day: he studied grammar from age twelve to fourteen (390–392),[10] rhetoric and humanities from fifteen to twenty (393–397) and finally theology and biblical studies (398–402).[10]

In 403, he accompanied his uncle to attend the "Synod of the Oak" in Constantinople,[11] which deposed John Chrysostom as Archbishop of Constantinople.[12] The prior year, Theophilus had been summoned by the emperor to Constantinople to apologize before a synod, over which Chrysostom would preside, on account of several charges which were brought against him by certain Egyptian monks. Theophilus had them persecuted as Origenists.[13] Placing himself at the head of soldiers and armed servants, Theophilus had marched against the monks, burned their dwellings, and ill-treated those whom he captured.[14] Theophilus arrived at Constantinople with twenty-nine of his suffragan bishops, and conferring with those opposed to the Archbishop, drafted a long list of largely unfounded accusations against Chrysostom,[15] who refused to recognize the legality of a synod in which his open enemies were judges. Chrysostom was subsequently deposed.

Patriarch of Alexandria[]

Theophilus died on 15 October 412, and Cyril was made Pope or Patriarch of Alexandria on 18 October 412, but only after a riot between his supporters and those of his rival Archdeacon Timotheus. According to Socrates Scholasticus, the Alexandrians were always rioting.[1]

Thus, Cyril followed his uncle in a position that had become powerful and influential, rivalling that of the prefect in a time of turmoil and frequently violent conflict between the cosmopolitan city's pagan, Jewish, and Christian inhabitants.[16] He began to exert his authority by causing the churches of the Novatianists to be closed and their sacred vessels to be seized.

Controversies[]

Dispute with the Prefect[]

Orestes, Praefectus augustalis of the Diocese of Egypt, steadfastly resisted Cyril's ecclesiastical encroachment onto secular prerogatives.[17]

Tension between the parties increased when in 415, Orestes published an edict that outlined new regulations regarding mime shows and dancing exhibitions in the city, which attracted large crowds and were commonly prone to civil disorder of varying degrees. Crowds gathered to read the edict shortly after it was posted in the city's theater. Cyril sent the grammaticus Hierax to discover the content of the edict. The edict angered Christians as well as Jews. At one such gathering, Hierax read the edict and applauded the new regulations, prompting a disturbance. Many people felt that Hierax was attempting to incite the crowd—particularly the Jews—into sedition.[18] Orestes had Hierax tortured in public in a theatre. This order had two aims: one to quell the riot, the other to mark Orestes' authority over Cyril.[19][17]

Socrates Scholasticus recounts that upon hearing of Hierex's severe and public punishment, Cyril threatened to retaliate against the Jews of Alexandria with "the utmost severities" if the harassment of Christians did not cease immediately. In response to Cyril's threat, the Jews of Alexandria grew even more furious, eventually resorting to violence against the Christians. They plotted to flush the Christians out at night by running through the streets claiming that the Church of Alexander was on fire. When Christians responded to what they were led to believe was the burning down of their church, "the Jews immediately fell upon and slew them" by using rings to recognize one another in the dark and killing everyone else in sight. When the morning came, Cyril, along with many of his followers, took to the city's synagogues in search of the perpetrators of the massacre.[20]

According to Socrates Scholasticus, after Cyril rounded up all the Jews in Alexandria he ordered them to be stripped of all possessions, banished them from Alexandria, and allowed their goods to be pillaged by the remaining citizens of Alexandria. Scholasticus indicates that all the Jews were banished, while John of Nikiû says only those involved in the ambush. Susan Wessel says that, while it is not clear whether Scholasticus was a Novationist (whose churches Cyril had closed), he was apparently sympathetic towards them, and makes clear Cyril's habit of abusing his episcopal power by infringing on the rights and duties of the secular authorities. Wessel says "...Socrates probably does not provide accurate and unambiguous information about Cyril's relationship to imperial authority".[21]

Nonetheless, with Cyril's banishment of the Jews, however many, "Orestes [...] was filled with great indignation at these transactions, and was excessively grieved that a city of such magnitude should have been suddenly bereft of so large a portion of its population."[20] Because of this, the feud between Cyril and Orestes intensified, and both men wrote to the emperor regarding the situation. Eventually, Cyril attempted to reach out to Orestes through several peace overtures, including attempted mediation and, when that failed, showed him the Gospels, which he interpreted to indicate that the religious authority of Cyril would require Orestes' acquiescence in the bishop's policy.[22] Nevertheless, Orestes remained unmoved by such gestures.

This refusal almost cost Orestes his life. Nitrian monks came from the desert and instigated a riot against Orestes among the population of Alexandria. These monks had resorted to violence 15 years before, during a controversy between Theophilus (Cyril's uncle) and the "Tall Brothers"; the monks assaulted Orestes and accused him of being a pagan. Orestes rejected the accusations, showing that he had been baptised by the Archbishop of Constantinople. A monk named Ammonius threw a stone hitting Orestes in the head. The prefect had Ammonius tortured to death, whereupon the Patriarch honored him as a martyr. However, according to Scholasticus, the Christian community displayed a general lack of enthusiasm for Ammonius's case for martyrdom. The prefect then wrote to the emperor Theodosius II, as did Cyril.[23][24]

Murder of Hypatia[]

The Prefect Orestes enjoyed the political backing of Hypatia, an astronomer, philosopher and mathematician who had considerable moral authority in the city of Alexandria, and who had extensive influence. Indeed, many students from wealthy and influential families came to Alexandria purposely to study privately with Hypatia, and many of these later attained high posts in government and the Church. Several Christians thought that Hypatia's influence had caused Orestes to reject all conciliatory offerings by Cyril. Modern historians think that Orestes had cultivated his relationship with Hypatia to strengthen a bond with the pagan community of Alexandria, as he had done with the Jewish one, in order to better manage the tumultuous political life of the Egyptian capital.[25] A mob, led by a lector named Peter, took Hypatia from her chariot and murdered her, hacking her body apart and burning the pieces outside the city walls.[26][27]

Neoplatonist historian Damascius (c. 458 – c. 538) was "anxious to exploit the scandal of Hypatia's death", and attributed responsibility for her murder to Bishop Cyril and his Christian followers.[28] Damascius's account of the Christian murder of Hypatia is the sole historical source attributing direct responsibility to Bishop Cyril.[29] Some modern studies represent Hypatia's death as the result of a struggle between two Christian factions, the moderate Orestes, supported by Hypatia, and the more rigid Cyril.[30] According to lexicographer William Smith, "She was accused of too much familiarity with Orestes, prefect of Alexandria, and the charge spread among the clergy, who took up the notion that she interrupted the friendship of Orestes with their archbishop, Cyril."[31] Scholasticus writes that Hypatia ultimately fell "victim to the political jealousy which at the time prevailed". News of Hypatia's murder provoked great public denunciation, not only of Cyril but of the whole Alexandrian Christian community.

Conflict with Nestorius[]

Another major conflict was between the Alexandrian and Antiochian schools of ecclesiastical reflection, piety, and discourse. This long running conflict widened with the third canon of the First Council of Constantinople which granted the see of Constantinople primacy over the older sees of Alexandria and Antioch. Thus, the struggle between the sees of Alexandria and Antioch now included Constantinople. The conflict came to a head in 428 after Nestorius, who originated in Antioch, was made Archbishop of Constantinople.[32]

Cyril gained an opportunity to restore Alexandria's pre-eminence over both Antioch and Constantinople when an Antiochine priest who was in Constantinople at Nestorius' behest began to preach against calling Mary the "Mother of God" (Theotokos). As the term "Mother of God" had long been attached to Mary, the laity in Constantinople complained against the priest. Rather than repudiating the priest, Nestorius intervened on his behalf. Nestorius argued that Mary was neither a "Mother of Man" nor "Mother of God" as these referred to Christ's two natures; rather, Mary was the "Mother of Christ" (Greek: Christotokos). Christ, according to Nestorius, was the conjunction of the Godhead with his "temple" (which Nestorius was fond of calling his human nature). The controversy seemed to be centered on the issue of the suffering of Christ. Cyril maintained that the Son of God or the divine Word, truly suffered "in the flesh."[33] However, Nestorius claimed that the Son of God was altogether incapable of suffering, even within his union with the flesh.[34] Eusebius of Dorylaeum went so far as to accuse Nestorius of adoptionism. By this time, news of the controversy in the capital had reached Alexandria. At Easter 429 A.D., Cyril wrote a letter to the Egyptian monks warning them of Nestorius's views. A copy of this letter reached Constantinople where Nestorius preached a sermon against it. This began a series of letters between Cyril and Nestorius which gradually became more strident in tone. Finally, Emperor Theodosius II convoked the Council of Ephesus (in 431) to solve the dispute. Cyril selected Ephesus[10] as the venue since it supported the veneration of Mary. The council was convoked before Nestorius's supporters from Antioch and Syria had arrived and thus Nestorius refused to attend when summoned. Predictably, the Council ordered the deposition and exile of Nestorius for heresy.

However, when John of Antioch and the other pro-Nestorius bishops finally reached Ephesus, they assembled their own Council, condemned Cyril for heresy, deposed him from his see, and labelled him as a "monster, born and educated for the destruction of the church".[35] Theodosius, by now old enough to hold power by himself, annulled the verdict of the Council and arrested Cyril, but Cyril eventually escaped. Having fled to Egypt, Cyril bribed Theodosius's courtiers, and sent a mob led by Dalmatius, a hermit, to besiege Theodosius's palace, and shout abuse; the Emperor eventually gave in, sending Nestorius into minor exile (Upper Egypt).[35] Cyril died about 444, but the controversies were to continue for decades, from the "Robber Synod" of Ephesus (449) to the Council of Chalcedon (451) and beyond.

Theology[]

Cyril regarded the embodiment of God in the person of Jesus Christ to be so mystically powerful that it spread out from the body of the God-man into the rest of the race, to reconstitute human nature into a graced and deified condition of the saints, one that promised immortality and transfiguration to believers. Nestorius, on the other hand, saw the incarnation as primarily a moral and ethical example to the faithful, to follow in the footsteps of Jesus. Cyril's constant stress was on the simple idea that it was God who walked the streets of Nazareth (hence Mary was Theotokos, meaning "God bearer", which became in Latin "Mater Dei or Dei Genitrix", or Mother of God), and God who had appeared in a transfigured humanity. Nestorius spoke of the distinct "Jesus the man" and "the divine Logos" in ways that Cyril thought were too dichotomous, widening the ontological gap between man and God in a way that some of his contemporaries believed would annihilate the person of Christ.

The main issue that prompted this dispute between Cyril and Nestorius was the question which arose at the Council of Constantinople: What exactly was the being to which Mary gave birth? Cyril affirmed that the Holy Trinity consists of a singular divine nature, essence, and being (ousia) in three distinct aspects, instantiations, or subsistencies of being (hypostases). These distinct hypostases are the Father or God in Himself, the Son or Word (Logos), and the Holy Spirit. Then, when the Son became flesh and entered the world, the pre-Incarnate divine nature and assumed human nature both remained, but became united in the person of Jesus. This resulted in the miaphysite slogan "One Nature united out of two" being used to encapsulate the theological position of this Alexandrian bishop.

According to Cyril's theology, there were two states for the Son of God: the state that existed prior to the Son (or Word/Logos) becoming enfleshed in the person of Jesus and the state that actually became enfleshed. The Logos Incarnate suffered and died on the Cross, and therefore the Son was able to suffer without suffering. Cyril passionately argued for the continuity of a single subject, God the Word, from the pre-Incarnate state to the Incarnate state. The divine Logos was really present in the flesh and in the world—not merely bestowed upon, semantically affixed to, or morally associated with the man Jesus, as the adoptionists and, he believed, Nestorius had taught.

Mariology[]

Cyril of Alexandria became noted in Church history because of his spirited fight for the title "Theotokos[36]" during the First Council of Ephesus (431).

His writings include the homily given in Ephesus and several other sermons.[37] Some of his alleged homilies are in dispute as to his authorship. In several writings, Cyril focuses on the love of Jesus to his mother. On the Cross, he overcomes his pain and thinks of his mother. At the wedding in Cana, he bows to her wishes. Cyril created the basis for all other mariological developments through his teaching of the blessed Virgin Mary, as the "Mother of God."[38] The conflict with Nestorius was mainly over this issue, and it has often been misunderstood. "[T]he debate was not so much about Mary as about Jesus. The question was not what honors were due to Mary, but how one was to speak of the birth of Jesus."[38] St. Cyril received an important recognition of his preachings by the Second Council of Constantinople (553 d.C.) which declared;

- "St. Cyril who announced the right faith of Christians" (Anathematism XIV, Denzinger et Schoenmetzer 437).

Works[]

Cyril was a scholarly archbishop and a prolific writer. In the early years of his active life in the Church he wrote several exegetical documents. Among these were: Commentaries on the Old Testament,[39] Thesaurus, Discourse Against Arians, Commentary on St. John's Gospel,[40] and Dialogues on the Trinity. In 429 as the Christological controversies increased, the output of his writings was so extensive that his opponents could not match it. His writings and his theology have remained central to the tradition of the Fathers and to all Orthodox to this day.

- Becoming Temples of God (Ναοὶ θεοῦ χρηματιοῦμεν) (in Greek original and English)

- Second Epistle of Cyril to Nestorius

- Third Epistle of Cyril to Nestorius (containing the twelve anathemas)

- Formula of Reunion: In Brief (A summation of the reunion between Cyril and John of Antioch)

- The "Formula of Reunion", between Cyril and John of Antioch

- Five tomes against Nestorius (Adversus Nestorii blasphemias)

- That Christ is One (Quod unus sit Christus)

- Scholia on the incarnation of the Only-Begotten (Scholia de incarnatione Unigeniti)

- Against Diodore of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia (fragments)

- Against the synousiasts (fragments)

- Commentary on the Gospel of Luke

- Commentary on the Gospel of John

- Against Julian the Apostate

- Cyrilli Alexandrini liber Thesaurus adversus hereticos a Georgio Trapesuntio traductus (in Latin and Greek)

Translations[]

- Festal letters 1-12, translated by Philip R. Amidon, Fathers of the Church vol. 112 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2009)

- Commentary on Isaiah, translated with an introduction by Robert Charles Hill (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2008)

- Commentary on the Twelve Prophets, translated by Robert C. Hill, 2 vols, Fathers of the Church vols 115-16 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2008) [translation of In XII Prophetas]

- Against those who are unwilling to confess that the Holy Virgin is Theotokos, edited and translated with an introduction by Protopresbyter George Dion. Dragas (Rollinsford, NH: Orthodox Research Institute, 2004)

- Norman Russell, Cyril of Alexandria (London: Routledge, 2000) [contains translations of selections from the Commentary on Isaiah; Commentary on John; Against Nestorius; An explanation of the twelve chapters; Against Julian]

- On the unity of Christ, translated and with an introduction by John Anthony McGuckin (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1995.)

- J A McGuckin, St Cyril of Alexandria: The Christological Controversy. Its History, Theology and Texts (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994) [contains translations of the Second and Third Letters to Nestorius; the Letters to Eulogius and Succensus; Cyril's Letters to the Monks of Egypt, to Pope Celestine, to Acacius of Beroea and to John of Antioch (containing the Formulary of Reunion), the Festal Homily delivered at St John's basilica, Ephesus, and the Scholia on the Incarnation]

- Letters 1-110, translated by John I McEnerney, Fathers of the Church vols 76-77 (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, c. 1987)

- Cyril of Alexandria. Selected Letters, edited and translated by Lionel R Wickham (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1983). [contains translations of the Second and Third Letters to Nestorius, the Letters to Acacius of Melitene and Eulogius, the First and Second Letters to Succensus, Letter 55 on the Creed, the Answers to Tiberius, the Doctrinal Questions and Answers, and the Letter to Calosirius,]

See also[]

- Catholic Church in Egypt

- Dyophysitism

- General Roman Calendar

- List of early Christian saints

- Saint Cyril of Alexandria, patron saint archive

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Henry Palmer Chapman (1908). "St. Cyril of Alexandria". In Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cyril (bishop of Alexandria)". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 706.

- ^ Gibbon, E., Milman, H. Hart. (1871). The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire. A new ed., Phila.: J. B. Lippincott & co. Volume 4, p. 509.

- ^ Mosshammer (2008) 193-194

- ^ Zuidhoek (2019) 67-74

- ^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice, 1969), pp. 95 and 116.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Norman Russell (2002). Cyril of Alexandria: The Early Church Fathers. Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 9781134673377.

- ^ Farmer, David Hugh (1997). The Oxford dictionary of saints (4. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-280058-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c https://st-takla.org/Saints/Coptic-Orthodox-Saints-Biography/Coptic-Saints-Story_1492.html

- ^ Schaff, Philip. "Cyril of Alexandria", The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. III.

- ^ "Saint Cyril of Alexandria", Franciscan Media

- ^ Palladius, Dialogus, xvi; Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, VI, 7; Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, VIII, 12.

- ^ Chrysostom Baur (1912), "Theophilus, The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. XIV (New York: Robert Appleton Company)

- ^ Photius, Bibliotheca, 59, in Migne, Patrologia Graecae, CIII, 105-113

- ^ Preston Chesser, "The Burning of the Library of Alexandria"., eHistory.com

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wessel, p. 34.

- ^ John of Nikiu, 84.92.

- ^ Socrates Scholasticus, vii.13.6-9

- ^ Jump up to: a b Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, born after 380 AD, died after 439 AD.

- ^ Wessel p. 22.

- ^ Wessel, p. 35

- ^ Socrates Scholasticus, vii.14.

- ^ Wessel, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Christopher Haas, Alexandria in Late Antiquity: Topography and Social Conflict, JHU Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8018-8541-8, p. 312.

- ^ Socrate Scolastico, vii.15.

- ^ Giovanni di Nikiu, 84.88-100.

- ^ "Whitfield, Bryan J., "The Beauty of Reasoning: A Reexamination of Hypatia and Alexandria", The Mathematics Educator, vol. 6, issue 1, p. 14, University of Georgia, Summer 1995" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ Dzielska 1996, p. 18.

- ^ Maria Dzielska, Hypatia of Alexandria, Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press, 1995 (Revealing Antiquity, 8), p. xi, 157. ISBN 0-674-43775-6

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Leo Donald Davis, The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology, Collegeville (Min.): The Liturgical Press, 1983, pp. 136–148. ISBN 0-8146-5616-1

- ^ Thomas Gerard Weinandy, Daniel A. Keating, The theology of St. Cyril of Alexandria: a critical appreciation; New York: T&T Clark Ltd, 2003, p. 49.

- ^ Nestorius, Second Epistle to Cyril "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 47.

- ^ The rejection of the term Theotokos by Nestorius Constantinople

- ^ PG 76,992, Adv. Nolentes confiteri Sanctam Virginem esse Deiparem, PG 76, 259.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gonzalez, Justo L. (1984). The Story of Christianity, Volume 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation. New York: HarperOne. p. 254. ISBN 9780060633158.

- ^ Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on Luke (1859), Preface, pp.i-xx.

- ^ Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on John, LFC 43, 48 (1874/1885). Preface to the online edition

References[]

- "Cyril I (412–444)". Official web site of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

Further reading[]

- Artemi, Eirini, « The mystery of the incarnation into dialogues "de incarnatione Unigenitii" and "Quod unus sit Christus" of St. Cyril of Alexandria », Ecclesiastic Faros of Alexandria, ΟΕ (2004), 145-277.

- Artemi, Eirini, «St Cyril of Alexandria and his relations with the ruler Orestes and the philosopher Hypatia », Ecclesiastic Faros of Alexandria, τ. ΟΗ (2007), 7-15.

- Artemi, Eirini, « The one entity of the Word Incarnate. α. Apollinarius' explanation, β. Cyril's explanation », Ecclesiastic Faros of Alexandria, τ. ΟΔ (2003), 293–304.

- Artemi, Eirini, The historical inaccurancies of the film Agora about the murder of Hypatia, Orthodox Press, τεύχ. 1819 (2010), 7.

- Artemi, Eirini, The use of the ancient Greek texts in Cyril's works, Poreia martyrias, 2010, 114-125.

- Artemi, Eirini, The rejection of the term Theotokos by Nestorius Constantinople more and his refutation by Cyril of Alexandria

- Artemi, Eirini, Свт. Кирилл Александрийский и его отношения с епархом Орестом и философом Ипатией by EIRINI ARTEMI (6 January 2014) Kindle Purchase. ASIN: B00ENJIJ20

- Kalantzis, George (2008). "Is There Room for Two? Cyril's Single Subjectivity and the Prosopic Union". St. Vladimir's Theological Quarterly. 52 (1): 95–110.

- Kalantzis, George (2010). "Single Subjectivity and the Prosopic Union in Cyril of Alexandria and Theodore of Mopsuestia". Studia Patristica. 47: 59–64. ISBN 9789042923744.

- Loon, Hans van (2009). The Dyophysite Christology of Cyril of Alexandria. Leiden-Boston: Basil BRILL. ISBN 978-9004173224.

- McGuckin, John A. (1994). St. Cyril of Alexandria: The Christological Controversy: Its History, Theology, and Texts. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004312906.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410563.

- Alden A. Mosshammer (2008) The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era: Oxford (ISBN 9780199543120)

- Wessel, Susan (2004). Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian Controversy: The Making of a Saint and of a Heretic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199268467.

- Konrad F. Zawadzki, Der Kommentar Cyrills von Alexandrien zum 1. Korintherbrief. Einleitung, kritischer Text, Übersetzung, Einzelanalyse, Traditio Exegetica Graeca 16, Leuven-Paris-Bristol, CT, 2015

- Konrad F. Zawadzki, Syrische Fragmente des Kommentars Cyrills von Alexandrien zum 1. Korintherbrief, Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum 21 (2017), 304-360

- Konrad F. Zawadzki, "Keiner soll die Lektüre der Schrift durcheinanderbringen!" Ein neues griechisches Fragment aus dem Johanneskommentar des Cyrill von Alexandrien, Biblica 99 (2018), 393-413

- Konrad F. Zawadzki, Der Kommentar Cyrills von Alexandrien zum 2. Korintherbrief. Einleitung, kritischer Text, Übersetzung, Einzelanalyse, Traditio Exegetica Graeca 18, Leuven-Paris-Bristol 2019

- Jan Zuidhoek (2019) Reconstructing Metonic 19-year Lunar Cycles (on the basis of NASA's Six Millennium Catalog of Phases of the Moon): Zwolle (ISBN 9789090324678)

External links[]

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Cyril of Alexandria. |

- Early Church Fathers Includes text written by Cyril of Alexandria

- Multilanguage Opera Omnia (Greek Edition by Migne Patrologia Graeca)

- St Cyril the Archbishop of Alexandria Eastern Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- Early Church Fathers: Cyril of Alexandria

- The Monophysism of St Cyril of Alexandria paper by Giovanni Costa on academia.edu

- Works by or about Cyril of Alexandria at Internet Archive

- Works by Cyril of Alexandria at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Five Metonic 19-year lunar cycles

- Dionysius Exiguus' Paschal table

- 376 births

- 444 deaths

- 5th-century Popes and Patriarchs of Alexandria

- Anti-Judaism

- 5th-century Christian saints

- 5th-century Christian theologians

- Church Fathers

- Doctors of the Church

- Saints from Roman Egypt

- Opponents of Nestorianism

- Catholic Mariology

- People from El Mahalla El Kubra

- Hypatia

- 5th-century Byzantine writers

- Anglican saints