Daniel Puente Encina

Daniel Puente Encina | |

|---|---|

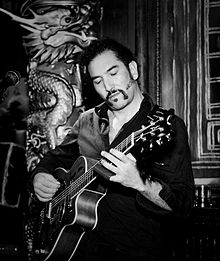

Daniel Puente Encina with Dobro (2013) | |

| Background information | |

| Born | Santiago de Chile |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1984–present |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts | |

| Website | www |

Daniel Puente Encina (Santiago de Chile, 1965) is a Chilean singer-songwriter, guitarist, film composer, producer and actor known for his bands[1] such as the anti-fascist Pinochet Boys from Santiago de Chile, Niños Con Bombas from Hamburg and Polvorosa from Barcelona, where he currently lives.[2]

Biography[]

Education and career[]

Daniel Puente Encina began teaching himself music at the age of four.[3] On his twelfth birthday, he father gave him a guitar and an hour's lesson. As an adolescent, he studied Musicology and Sociology at the University of Chile.[4]

Los Pinochet Boys (1984–1987)[]

In his native Chile, he is better known as "Daniel Puente" [5] o "Dani Puente",[6] founder, lead singer and bass player of the anti-fascist new wave/post-punk group formed with a few friends[7] in the Santiago of the mid-1980s, one of the most repressive[8] periods of Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship.[9] His first group, it formed part of the Chilean revolution, as noted in a number of books, documentaries[10] and the fourth episode of Chilean drama TV series Los 80[11][12] by Canal 13. In 1984, Carlos Fonseca, a friend of the group and presenter of the programme Fusión contemporánea on Santiago's Radio Beethoven station, offered them a contract with the record company Fusión, owned by his father Mario Fonseca, on the condition that they changed its provocative name –something the group refused to do. The contract was later offered to group Los Prisioneros.[13] Los Pinochet Boys' clandestine concerts were routinely broken up by the police shortly after they began, soon sparking to a youth movement[14][15] in the Chilean capital. Its four members were harassed, threatened and persecuted for their irreverent attitude and wild performances, and often arrested for having dyed hair.[13] In 1987, after only three years together, Los Pinochet Boys were unofficially forced by the military regime to leave the country.[16] After almost two years of organising their own concerts and touring with, amongst others, the Inocentes and in Brazil and Todos Tus Muertos in Argentina, the group returned to Chile to play an active role[3] in the No campaign for the 1988 Chilean national plebiscite, which put an end to Pinochet's regime. Their sole musical legacy consisted of two cassette recordings: "Botellas contra el pavimento"/"En mi tiempo libre" and "La música del general"/"Esto es Pinochet Boys", which have been copied on numerous occasions over the past decades.[9] In 2012, record company Hueso Records from New York remastered both to produce a 500-copy limited edition 7-inch record entitled Pinochet Boys.

Niños Con Bombas (1994–1999)[]

In 1989, after travelling through Europe, "Daniel Puente" moved to West Berlin a few months before fall of the Wall. There, he became friends with members of Einstürzende Neubauten, who would later on play an important role introducing him to a wider audience.[17] After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Puente Encina settled in Hamburg, where he founded the multicultural group , sharing the stage with a number of bands from the so-called Hamburger Schule indie scene, such as Tocotronic, Blumfeld and Die Goldenen Zitronen. In 1995, Niños Con Bombas won the "John Lennon Talent Award"[18][19] and signed deals with Stuttgart label , Potomak and New York-based international alternative Latin record company ,[20] founded by Bad Religion's original drummer Jay Ziskrout. The band released two albums: (1996) produced by Chris Rolffsen and (1997) produced by Thies Mynther. Due to the MTV Music Television Video Rotation[21] and radio airplays, songs such as Skreamska and Postcard were popular in Europe, South America and the US, which the group toured in 1997, with concerts in New Jersey, Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, Virginia, New York,[22] Los Angeles and San Francisco. In 1998, they played in front of a crowd of 90,000 at the Rock al Parque festival[23][24] in Bogotá, Colombia and, in 1999, at Austin's South by Southwest (SXSW) Music Festival, with The New York Times saying "one of the most interesting performances was that of Niños Con Bombas".[25] In South America, Puente Encina and his group toured countries such as Chile, Argentina, Mexico, Brazil and Colombia[20] and performed its alternative Latin Jazz-Ska-Rock sound in Europe as openers for Einstürzende Neubauten. In 1999, Niños Con Bombas moved to Los Angeles, but due to internal differences split shortly afterwards.[26]

Polvorosa (2000–2011)[]

In 2000, Puente Encina moved back to Europe and began performing and producing under the name "Polvorosa" in Barcelona, Spain. Once again changing musical direction, he created a new style: "Latin-Elektro-Clash". "Polvorosa" toured Europe and, as openers for Chambao and Ojos de Brujo, the entire Iberian peninsula. In 2004, he released the album . The track Behind de mi House[27][28] became known worldwide after its video, created by German film director , was chosen by MTV Music Television for its 2004 DVD compendium "Los Vídeos Mas Espectaculares"[29] ("The Most Spectacular Videos"). In 2009, Puente Encina abandoned electronica in favour of a more natural feel and more organic sound.[30] The end result was a mix of Latin, desert rock, jazz and world music. In 2011, he was chosen by Spanish nonprofit organization Instituto Cervantes in Tel Aviv to give a number of concerts in Israel.

Solo career[]

In 2012, Daniel Puente Encina recorded his first album under his own name: ,[31] a blues-based work noteworthy for the minimalism of its instrumentation. Its ten tracks included an updated version of "Botellas contra el pavimento" by way of a personal tribute to his first band, "Pinochet Boys". The album was released in spring 2012 and launched in his native Chile, with a subsequent tour of Spain,[32] Germany and Denmark. In 2013, before continuing with his German tour, with the support of Catalan governmental organisation Institut Ramon Llull, he invited New York soul singer Mónica Green, granddaughter of Margaret "Maggie" Price of , to the studio to take part in the recording of new versions of Lío and Mike Tysonboth songs from this album, to give the chorus a touch of Motown.[33]

July 2014 saw Puente Encina release [34][35] (Chocolate with Chilli), the second album under his own name, containing a mixture of genres and described on his website as a personal "Best Of" album, a compilation of his favourite previously unreleased compositions. It reflects a wide variety of styles ranging from South American music, rhythm and blues and Caribbean sounds. He promoted the album in Denmark, during the Copenhagen Jazz Festival, in Germany and Italy and began another European tour in 2015. Puente Encina was invited by the Cuban Music Institute's National Centre for Popular Music to give four performances at the 31st "Jazz Plaza" Havana International Jazz Festival in December 2015.

In 2016, for the International Workers' Day, he published "Freire", an animated music video created by Chilean illustrator and director Cristián Montes Lynch and his team.[36] With the song from his album Chocolate con Ají and its corresponding video clip, Daniel Puente Encina reflects his critical view of "the unjust, dysfunctional system that is capitalism" and draws attention to the exploitation of mining workers throughout the Andes.[37]

In 2017 he invited Majorcan organist and pianist Llorenç Barceló to record a piano version of his smooth-jazz classic Odd Desire.[38]

(Blood and Salt), his third solo album, published in 2019,[39] was inspired by the mark left by Africa on the criolla music of Chile, Peru and Argentina.[40][41] In 2019 Daniel Puente Encina was awarded with , (Latin UK Awards), Runner-up in the category European Jazz/ Folk Act of the year.[42][43]

Style and influences[]

Daniel Puente Encina has created—and recreated—a number of different styles of music. With Los Pinochet Boys, he offered a mix of new wave and post-punk. With Niños Con Bombas, he fused Latin, jazz, ska and rock with punk elements.[18] In 2004, under the name 'Polvorosa, he invented a new style he dubbed "Latin-Elektro-Clash".[44] 2012's Disparo is a minimalist, blues-based album[45] fusing R&B, Son cubano, Reggae and Bolero elements with African and Afro-Peruvian rhythms. His 2014 album Chocolate con Ají mixes South American musical influences, rhythm and blues and Caribbean music,[46] providing a listening experience embracing everything from boogaloo blues, 60s Latin soul, samba funk and Latin rap to Dixie country ska, slow swing and indie-Cuban ballads.[47] According to his website, he calls such creations "Furious Latin Soul", "Dirty Boogaloo", "Rebel Tango", "Flamenco Tex-Mex" and "Dixie Country Ska". (2019) stands out for its organic mixture.[40][39] with Afro-Peruvian rhythms with dashes of Flamenco, Peruvian waltz, Argentinian Zamba, Guaguancó, Cueca, Latin Swing and Boleros.[40] The album is considered as a tribute to Latin American music "inspired by the mark that Africa has left on the Creole music of Peru, Argentina and of course Chile, his country of origin."[41]

Although he mainly sings in Spanish, Puente Encina occasionally uses a mix of different languages in his lyrics. With Niños Con Bombas, he wrote songs such as Ton Ego n'est pas toi, sung partly in French. With Polvorosa, he sang in Portuñol, a mix of Portuguese and Spanish, in English and Spanish alone, and also in Spanglish, the mix of the latter two languages used mainly by the Latino community in the US.

He plays a variety of guitars when performing, frequently swapping between his Dobro, resonator, 1962 Höfner electric and Camps classical guitars. Since 2018 Daniel Puente Encina belongs to the official artist roster of Canadian Godin (guitar manufacturer) in Germany and plays a Godin Multiac Grand Concert Duet Ambiance guitar, a hybrid between electric guitar and acoustic guitar.

Film and TV[]

In the 1990s, Niños Con Bombas caught the eye of Turkish-German film director Fatih Akin, who contacted Daniel Puente Encina, marking the start of long working relationship.[48][49] Puente Encina's songs Cocomoon and Nunca Diré formed part of the soundtrack of the Akin's first feature, 1998's crime film Short Sharp Shock. Puente Encina also composed songs such as El Amor se demora and Ramona for the director's road movie Im Juli (in July 2000), in which he had a cameo role with Niños Con Bombas, singing the song Velocidad. He also wrote the song Not here for the multi-award-winning drama film Head On (2004).

In 2012, Daniel Puente Encina was interviewed during his Chilean tour by Joe Vasconcellos for El baile de los que sobran,[50] a documentary on singer Jorge González, as well as by for the Via X TV programme Red Hot Chilean People,[51] for which he also performed five songs live. Lewin was a famous MTV video jockey[52] and had previously interviewed Puente Encina in the 90s for MTV Latin America in Miami.

In April 2015, Daniel Puente Encina played a supporting role[53] as "Sadler", P.E.N. congress visitor in Buenos Aires, in Maria Schrader's film Stefan Zweig: Farewell to Europe (Original title in German: Vor der Morgenröte), awarded by the European Film Awards ("People’s Choice Award for Best European Film" for Maria Schrader), Bavarian Film Awards (Maria Schrader as Best Director), German Film Critics Award (Josef Hader as Best Actor), German Film Critics Award (Wolfgang Thaler as Best Cinematography) and the Austrian Film Award ( Monika Fischer-Vorauer and Andreas Meixner for Best Make Up) in 2017. In 2016 the narrative film was nominated for the Deutscher Filmpreis (German Film Awards, also called Lola Awards) in two categories: Maria Schrader for Best Director and Barbara Sukowa for Best Supporting Actress and Maria Schrader for the Variety Piazza Grande Award by the Locarno International Film Festival. In 2017 the movie was nominated by the European Film Awards (Josef Hader as Best European Actor), Austrian Film Award (Josef Hader as Best Actor), Palm Springs International Film Festival (FIPRESCI Prize for Maria Schrader as Best Foreign Language Film), German Film Critics Award (Maria Schrader for Best Film, Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg for Best Screenplay, Aenne Schwarz as Best Actress) and by the Jupiter Award (Josef Hader as Best German Actor).

Discography[]

Pinochet Boys[]

- 2012 – Pinochet Boys, 7" Vinyl, recorded 1984

Niños Con Bombas[]

- 1996 – Niños Con Bombas de tiempo en el momento de la explosión (Album)

- 1997 – El Niño (Album)

- 1998 – Short Sharp Shock, crime film by Fatih Akin, (Songs "Cocomoon" and "Nunca Diré": Original Soundtrack)

- 1998 – Skaliente (compilation)

- 1998 – Rolling Stone New Voices, Vol. 21 (compilation)

- 1999 – Elektro Latino Vol.1 (compilation)

- 2000 – Im Juli (English: In July) road movie by Fatih Akin, (Song "Ramona": Original Soundtrack / Cameo: "Velocidad" live)

- 2004 – Head-On, German: "Gegen die Wand", multi-award-winning drama film by Fatih Akin (Songs "Postcard" and "Cocomoon": Original Soundtrack)

Polvorosa[]

- 2000 – "Popkomm Sampler" (compilation)

- 2000 – Im Juli (English: In July) road movie by Fatih Akin, (Song "El amor se demora": Original Soundtrack)

- 2004 – Head-On, German: "Gegen die Wand", multi-award-winning drama film by Fatih Akin (Song "Not here": Original Soundtrack)

- 2004 – Radical Car Dance (Album)

- 2004 – "Electronic Latin Freaks" (compilation)

- 2004 – "Barcelona Raval Sessions" (compilation)

- 2006 – "Sex, City, Music: Barcelona" (compilation)

Solo albums[]

- 2012 – Disparo (Shot), (Album)

- 2014 – Chocolate con Ají (Chocolate with Chili), (Album)

- 2019 – Sangre y sal (Blood and salt), (Album)

Singles[]

- 2013 – Mike Tyson Radio Mix (with Monica Green)

- 2013 – Lío Radio Mix (with Monica Green)

- 2016 – Freire (video clip created by Chilean illustrator Cristián Montes Lynch)

- 2017 – Odd Desire Piano Version (with Majorcan pianist Llorenç Barceló)

- 2019 – Love is the only sound

- 2019 – Frente al mar

- 2019 – Bipolar

- 2019 – Falta de ti

Selected filmography[]

Documentary film[]

|

Awards and Nominations[]

Awards

- 1995: for

- 2004 MTV Spain "The most spectacular videos 2004", Song "Behind de mi House" by Polvorosa. Artdesign

- 2019 , Runner-up in the category "European Jazz/Folk Act of the Year"

References[]

- ^ García, Marisol (April 18, 2012). "Daniel Puente, nómade solitario" [Daniel Puente, solitary nomad]. Qué pasa (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ "Daniel Puente Encina's Official Website".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Damm, Florian (May 1, 2015). "Daniel Puente Encina im Interview mit Florian Damm" [Daniel Puente Encina is interviewed by Florian Damm]. Soundcheck (in German). 120 minutes in. Radio Okerwelle 104,6. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ^ Aguayo, Emiliano (2014). Las Voces de los '80 [The Voices of the 80s] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: RiL. p. 65.

- ^ Ibarz, Joaquim (October 19, 1986). "Los hijós rockeros de Pinochet se rebelan. El movimiento pop chileno sale de las catacumbas a las que fue condenado por la dictadura militar" [Pinochet's rocker children rebel. The Chilean pop movement comes out of the catacombs to which it was condemned by the military dictatorship.]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Ponce, David (December 24, 2012). "Gonzalo Donoso presenta "Retratos músicos chilenos" – Esto es memoria fotográfica" [Gonzalo Donoso presents "Chilean Musician's Portraits" – This is photographic memory.]. El Mercurio on-line (Emol) (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Urzua, Patricio (October 2008). "Los Pinochet Boys en Rolling Stone: Rock y dictadura: bailando en la oscuridad" [Los Pinochet Boys in the Rolling Stone: Rock and dictatorship: dancing in the darkness.]. El Blog de Midia (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Durán, Amanda (May 2012). "Daniel Puente: "Soy el tipo que está encerrado en su taller, porque lo llevo conmigo, en mi guitarra"" [Daniel Puente: "I am the type that is shut up in his studio, because I take it with me, in my guitar"] (PDF). El Ciudadano Nº 124 (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Godoy, José Luis (April 23, 2012). "Señores Pasajeros con José Luis Godoy. Entrevista con Daniel Puente Encina" [Señores Pasajeros with José Luis Godoy. Interview with Daniel Puente Encina]. Señores Pasajeros (in Spanish). 15:49 minutes in. Radio Uno 97.1 FM. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ El documental de Pinochet Boys [The Pinochet Boys documental] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: The Clinic TV / Nuez TV. June 22, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ Jürgensen, Mauricio (November 8, 2010). "La intimidad con que se construye el nuevo ciclo de Los 80" [The intimacy with which the new cycle of The 80's is constructed.]. La Tercera (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Publimetro, Editorial (November 8, 2010). "Los 80' reviven a los "Pinochet boys" y arrasan en sintonía" [The 80s revive the "Pinochet boys" with triumphant reception.]. Publimetro (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cossio, Hector (October 1, 2014). "Daniel Puente Encina: de vocalista de los míticos Pinochet Boys al músico total que se consolida en Europa" [Daniel Puente Encina: from vocalist of mythical Pinochet Boys to total musician becoming consolidated in Europe]. El Mostrador (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ García, Marisol (March 1, 2013). "Pinochet Boys" [Pinochet Boys]. EDA. Educación Antiautoritaria, Edición Nº 9 (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Karweik, Hans (May 21, 2013). ""Musik hat einen unfassbaren Einfluss" – WN-Exklusiv-Gespräch mit Daniel Puente Encina. Der Komponist kreierte den "Furious Latin Soul" in Spanien" ["Music has an unfathomable influence" – WN exclusive interview with Daniel Puente Encina. The composer created the "Furious Latin Soul" in Spain.]. Wolfsburger Nachrichten (in German). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Nurmi, Tilo (April 11, 2012). "Entrevista a Daniel Puente Encina: El amor como acto de rebeldía" [Interview with Daniel Puente Encina: Love as act of rebelliousness.]. Absenta Musical (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Ponce, David (April 11, 2012). "Daniel Puente Encina – Ciudadano (fuera) del mundo" [Daniel Puente Encina – Citizen (outside) of the world]. El Mercurio On-line (Emol) (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stark, Jürgen (April 21, 1995). "Aufstieg aus dem Untergrund" [Rise from the underground]. Hamburger Abendblatt (in German). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Stark, Jürgen (June 3, 1995). "Gewinner des "John Lennon Förderpreises '95": die Gruppen SubOrange Frequency und Ninos Con Bombas" [Winners of the "John Lennon Talent Award '95": the bands SubOrange Frequency and Ninos Con Bombas]. Rolling Stone (in German). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hurtado, Ana María (April 1998). Recuerdos de verano – Niños Con Bombas [Summer memories – Niños Con Bombas] (in Spanish). Revista Rock & Pop Nº47.

- ^ Vidal, Vadim (May 2, 2012). "Daniel Puente Encina: El Pinochet Boys solitario" [Daniel Puente Encina: The solitary Pinochet Boys]. Paula (in Spanish). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Lannert, John (September 13, 1997). Latin Notas [Latin Notes]. Billboard. p. 40.

- ^ Redacción, EL TIEMPO (October 23, 1998). "Tres ángelitos que juegan con material musicalmente explosivo" [Three little angels that play with musically explosive material]. El Tiempo (Colombia) (in Spanish). Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Instituto Distrital de las Artes, Editorial (1998). "1998 Artistas" [1998 Artists]. Rock al Parque (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (March 24, 1999). "Correction: March 29, 1999 – The Pop Life; Tough Times: Rock's Incubator Turns Down the Heat". The New York Times. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Panes, Andrés (May 2012). "Daniel Puente Encina – El retorno del cowboy espacial" [Daniel Puente Encina – The return of the space cowboy]. Rockaxis, Nº 111, pages 82–83 (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Arnold, Florian (February 24, 2015). "Der Rebell, der aus Chile kam" [The rebel who came from Chile]. Braunschweiger Zeitung (in German). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Ordovás, Jesús (May 19, 2004). "Entrevista a Maga y a Polvorosa" [Interview with Maga and Polvorosa]. Diario Pop (in Spanish). La Web de Los Oyentes de Radio3. Radio3, RNE. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ MTV Magazine (2004). "Los Videos Mas Espectaculares" [The Most Spectacular Videos]. Discogs (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Wilke, Katrin; Romero-Castillo, Evan (February 5, 2011). "Polvorosa: el lado oscuro de la música "latina"" [Polvorosa: the dark side of "Latin" music]. Deutsche Welle (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Panes, Andrés (May 15, 2012). "Daniel Puente Encina – Disparo" [Daniel Puente Encina – Disparo (Shot)]. Rockaxis (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Mula, Iván F. (September 14, 2012). "Latin soul de la controversia" [Latin soul of the controversy]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Fierro, Roberto (June 2, 2013). "Monica Green y Daniel Puente Encina graban juntos" [Monica Green and Daniel Puente Encina record together]. The Concert in Concert (in Spanish). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Salazar, Carlos (June 23, 2014). "Daniel Puente, ex Pinochet Boys: "Fuimos los primeros hipsters"" [Daniel Puente, ex-Pinochet Boys: "We were the first hipsters"]. La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Carrasco, Juan Guillermo (September 12, 2014). "Daniel Puente Encina – Chocolate Con Ají" [Daniel Puente Encina – Chocolate Con Ají (Chocolate with Chilli)]. Rockaxis (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ El Mostrador, Cultura+Ciudad (May 2, 2016). "Daniel Puente Encina lanza su video clip de animación "Freire"" [Daniel Puente Encina launches his animated video clip "Freire"]. El Mostrador (in Spanish). Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ "News – Daniel Puente Encina's Official Website".

- ^ "Bio – Daniel Puente Encina's Official Website".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Plasma Magazine, Dano (July 8, 2019). "Sangre y Sal – Daniel Puente Encina" [Sangre y Sal – Daniel Puente Encina]. PlasmaMagazineMX (in Spanish). Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Editorial, Cancioneros (May 18, 2019). "Novedad Discográfica – Daniel Puente Encina anuncia "Sangre y sal", su tercer álbum solista" [New releases – Daniel Puente Encina announces «Sangre y sal», his third solo album]. Cancioneros (in Spanish). Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pérez, Eloy (October 2, 2019). "Daniel Puente Encina – Sangre y Sal (Polvorosa)" [Daniel Puente Encina – Sangre y Sal (Polvorosa)]. Ruta66 (in Spanish). Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ The Lukas, Official website (November 6, 2019). "The winners 2019". The Lukas. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Editorial, Rockaxis (November 14, 2019). "Daniel Puente Encina recibe importante premio en el extranjero – El ex Pinochet Boys fue reconocido en el Reino Unido" [Daniel Puente Encina receives important award abroad – The former Pinochet Boys was recognized in the United Kingdom]. Rockaxis (in Spanish). Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Arbejderen, Editorial (September 11, 2013). "En musikalsk rebel og en latin soul-man kommer til Danmark" [A musical rebel and a Latin soul-man comes to Denmark]. Arbejderen (in Danish). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Knobloch, Andreas (April 25, 2013). "Ein Punker bekommt den (Afro-)Blues" [A punk gets the (Afro-) blues]. Mallorca Zeitung (in German). Palma de Mallorca.

- ^ Steger, Leonie (February 2015). "Daniel Puente Encina im Interview "Immer noch ein musikalischer Rebell"" [Interview with Daniel Puente Encina"Still a musical rebel"]. Indigo (in German). Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Schmidt, Hanna (January 7, 2015). "Daniel Puente Encina "Meine Texte sind ein Urschrei des Seins"" [Daniel Puente Encina "My lyrics are a primal scream of being"]. WAZ (in German). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Sandgathe, Laura (September 5, 2014). "Er schrieb Filmmusik zu "Gegen die Wand" – Daniel Puente Encina bringt Lateinamerika nach Duisburg" [He wrote film music for "Head On" – Daniel Puente Encina brings Latin America to Duisburg]. Rheinische Post (in German). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Kalle, Kathleen (June 2013). "Rebell und Weltbürger" [Rebel and cosmopolite]. Indigo (in German). Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Vasconcellos, Joe; Freund, Cristián; Fuentes, Fernando; Sepúlveda, Rodrigo; Giesen, Werner (September 9, 2012). "El baile de los que sobran" [The dance of those who remain]. Doremix (in Spanish). TVN Chile.

- ^ Lewin, Alfredo (February 4, 2013). "Lunes en Red Hot Chilean People: Daniel Puente Encina" [Monday in Red Hot Chilean People: Daniel Puente Encina]. Red Hot Chilean People (in Spanish). VIA X HD Chile. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Cobo-Hanlon, Leila (November 22, 1994). "Heating Up the MTV Latino Connection: Television: VJ Alfredo Lewin, who has become almost as popular as the rock stars he interviews, wants to take the network to new heights as a cultural force". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ Nurmi, Tilo (May 26, 2015). "Mira el show en vivo de Daniel Puente Encina en Berlín" [Watch Daniel Puente Encina's live show]. Absenta Musical (in Spanish). Retrieved March 29, 2016.

Further reading[]

- Ramón, Emilio; Vargas, Ricardo (2020). Disco punk: 20 postales de una discografía local [Punk album: 20 postcards from a local discography] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Santiago-Ander Editorial. ISBN 978-9-5699-2120-9.

- Canales Cabrera, Jorge (2019). Punk chileno, 1986 – 1996: 10 años de autogestión [Chilean Punk, 1986 – 1996: 10 years of self-management] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Camino y No Patria.

- Greene Jr., James (2017). Brave Punk World: The International Rock Underground from Alerta Roja to Z-Off. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-144-226-984-2.

- Aguayo, Emiliano (2014). Las Voces de los '80 [The Voices of the 80s] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: RiL. ISBN 978-956-284-914-2.

- Vila, Pablo (2014). The Militant Song Movement in Latin America: Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Lexington Books, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7391-8324-3.

- García, Marisol (2013). Canción Valiente 1960–1989. Tres décadas de canto social y político en Chile [Brave Song 1960–1989. Three decades of social and political singing in Chile] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Ediciones B Chile. ISBN 978-956-304-144-6.

- Donoso, Gonzalo (2012). Retratos Músicos Chilenos 1986–2012 [Chilean Musicians Portraits 1986–2012] (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Pehuen. ISBN 978-956-16-0570-1.

- Conejeros, Miguel (2008). Pinochet Boys, Legitimando el mito [Pinochet Boys, legitimizing the myth]. Santiago de Chile: Midia Comunicación. ISBN 978-956-8331-08-5.

- Contardo, Óscar; García, Macarena (2005). La era ochentera [The era of the eighties]. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones B Chile. ISBN 978-956-304-006-7.

External links[]

- Chilean songwriters

- Chilean rock singers

- Living people

- Chilean male singers

- Chilean male actors

- Spanish-language singers