Daphne du Maurier

Daphne du Maurier | |

|---|---|

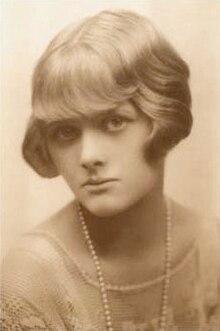

du Maurier around 1930 | |

| Born | 13 May 1907 London, England |

| Died | 19 April 1989 (aged 81) Fowey, Cornwall, England |

| Occupation | Novelist and playwright |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1931–1989 |

| Genre | Literary fiction, thriller |

| Notable works | Rebecca Frenchman's Creek The Scapegoat The Birds Jamaica Inn My Cousin Rachel |

| Notable awards | National Book Award (U.S.) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents | Sir Gerald du Maurier (father) Muriel, Lady du Maurier (mother) |

| Relatives | George du Maurier (grandfather) Angela du Maurier (sister) Jeanne du Maurier (sister) Guy du Maurier (uncle) Sylvia Llewelyn Davies (aunt) |

| Website | |

| www | |

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning, DBE (/duː ˈmɒrieɪ/; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was an English author and playwright.

Although she is classed as a romantic novelist, her stories have been described as "moody and resonant" with overtones of the paranormal. Her bestselling works were not at first taken seriously by critics, but have since earned an enduring reputation for narrative craft. Many have been successfully adapted into films, including the novels Rebecca, Frenchman's Creek, My Cousin Rachel, and Jamaica Inn, and the short stories The Birds and Don't Look Now/Not After Midnight.

Du Maurier spent much of her life in Cornwall, where most of her works are set. As her fame increased, she became more reclusive.[1]

Her parents were actor/manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and stage actress Muriel Beaumont. Her grandfather was writer and cartoonist George du Maurier.

Early life[]

Daphne du Maurier was born in London, the middle of three daughters of prominent actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and actress Muriel Beaumont. Her mother was a maternal niece of journalist, author, and lecturer William Comyns Beaumont.[2] Her grandfather was author and Punch cartoonist George du Maurier, who created the character of Svengali in the 1894 novel Trilby. Her elder sister, Angela du Maurier, also became a writer, and her younger sister Jeanne was a painter.[3]

Du Maurier's family connections helped her establish her literary career, and she published some of her early work in Beaumont's Bystander magazine. Her first novel, The Loving Spirit, was published in 1931. Du Maurier was also a cousin of the Llewelyn Davies boys, who served as J. M. Barrie's inspiration for the characters in the play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up.[3]

As a young child, du Maurier met many prominent theatre actors, thanks to the celebrity of her father. On meeting Tallulah Bankhead, du Maurier was quoted as saying that Bankhead was the most beautiful creature she had ever seen.[4]

Novels, short stories, and biographies[]

The novel Rebecca (1938) was one of du Maurier's most successful works. It was an immediate hit, selling nearly 3 million copies between 1938 and 1965. The novel has never gone out of print, and has been adapted for both stage and screen several times. In the U.S. du Maurier won the National Book Award for favourite novel of 1938 for the book, voted by members of the American Booksellers Association.[5] In the UK, it was listed at number 14 of the "nation's best-loved novel"s on the BBC's 2003 survey The Big Read.[6]

Other significant works include The Scapegoat, The House on the Strand, and The King's General. The last is set in the middle of the first and second English Civil Wars,[clarification needed] written from the Royalist perspective of du Maurier's adopted Cornwall.[clarification needed] Unusually for du Maurier it has a female narrator.[7]

Several of du Maurier's other novels have also been adapted for the screen, including Jamaica Inn, Frenchman's Creek, Hungry Hill, and My Cousin Rachel. The Hitchcock film The Birds (1963) is based on a treatment of one of her short stories, as is the film Don't Look Now (1973). Of the films, du Maurier often complained that the only ones she liked were Hitchcock's Rebecca and Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now.

Hitchcock's treatment of Jamaica Inn was disavowed by both director and author, due to a complete re-write of the ending to accommodate the ego of its star, Charles Laughton. Du Maurier also felt that Olivia de Havilland was wrongly cast as the anti-heroine of My Cousin Rachel.[8] Frenchman's Creek fared better in a lavish Technicolor version released in 1944. Du Maurier later regretted her choice of Alec Guinness as the lead in the film of The Scapegoat, which she partly financed.[9]

Du Maurier was often categorised as a "romantic novelist", a term that she deplored,[10] given her novels rarely have a happy ending, and often have sinister overtones and shadows of the paranormal. In this light, she has more in common with the "sensation novels" of Wilkie Collins and others, which she admired.[9] The obituarist Kate Kellaway wrote: "Du Maurier was mistress of calculated irresolution. She did not want to put her readers' minds at rest. She wanted her riddles to persist. She wanted the novels to continue to haunt us beyond their endings."[11]

Du Maurier's novel Mary Anne (1954) is a fictionalised account of her great-great-grandmother, Mary Anne Clarke née Thompson (1776–1852), who, from 1803 to 1808, was mistress of Frederick Augustus, Duke of York and Albany (1763–1827). He was the "Grand Old Duke of York" of the nursery rhyme, a son of King George III, and brother of King George IV and King William IV. The central character of her last novel, Rule Britannia, is an aging actress, thought to be based on Gladys Cooper (to whom it is dedicated).[citation needed]

Du Maurier's short stories are darker: The Birds, Don't Look Now, The Apple Tree, and The Blue Lenses, are finely crafted tales of terror that shocked and surprised her audience in equal measure.[citation needed] As her biographer Margaret Forster wrote, "She satisfied all the questionable criteria of popular fiction, and yet satisfied too the exacting requirements of 'real literature'."[citation needed]

The discovery, in 2011, of a collection of du Maurier's forgotten short stories, written when the author was 21, provides some insight into her mature style. One of them, The Doll, concerns a young woman's obsession with a mechanical male sex doll; it has been deemed by du Maurier's son Kit Browning to be "quite ahead of its time".[12]

In later life, she wrote non-fiction, including several biographies such as Gerald, her father's biography. The Glass-Blowers traces her French Huguenot ancestry and vividly depicts the French Revolution. The du Mauriers traces the family's move from France to England in the 19th century.[citation needed]

The House on the Strand (1969) combines elements of "mental time-travel", a tragic love affair in 14th-century Cornwall, and the dangers of using mind-altering drugs. Her final novel, Rule Britannia (1972), satirises resentment of British people in general, and Cornish people in particular, at increasing American involvement in UK affairs.[citation needed]

Plays[]

Du Maurier wrote three plays. Her first was an adaptation of her novel Rebecca, which opened at the Queen's Theatre in London on 5 March 1940 in a production by George Devine, starring Celia Johnson and Owen Nares as the De Winters and Margaret Rutherford as Mrs Danvers. After 181 performances, the production transferred to the Strand Theatre, with taking over as the second Mrs De Winter and Mary Merrall as Mrs Danvers, with a further run of 176 performances.

In 1943 she wrote the autobiographically inspired drama The Years Between about the unexpected return of a senior officer, thought killed in action, who finds that his wife has taken his seat as Member of Parliament (MP) and has started a romantic relationship with a local farmer. It was first staged at the Manchester Opera House in 1944 and then transferred to London, opening at Wyndham's Theatre on 10 January 1945, starring Nora Swinburne and Clive Brook. The production, directed by Irene Hentschel, became a long-running hit, completing 617 performances. It was revived by Caroline Smith at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond upon Thames on 5 September 2007, starring Karen Ascoe and Mark Tandy.[13]

Her third play, September Tide, portrays a middle-aged woman whose bohemian artist son-in-law falls in love with her. Again directed by Irene Hentschel, it opened at the Aldwych Theatre on 15 December 1948 with Gertrude Lawrence as Stella. It closed in August 1949 after 267 performances.

Personal names, titles and honours[]

She was known as Daphne du Maurier from 1907 to 1932, when she married Frederick Browning. Still writing as Daphne du Maurier (1932–1946), she was otherwise titled Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning (1946–1969). When she was elevated to the Dame Commander of the British Empire in 1969, she was titled Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning DBE (1969–1989), but she never used the title.

According to her biographer Margaret Forster, she told no one about the honour, so that even her children learned of it only from the newspapers. "She thought of pleading illness for the investiture, until her children insisted it would be a great day for the older grandchildren. So she went through with it, though she slipped out quietly afterwards to avoid the attention of the press."[14]

Accusations of plagiarism[]

Shortly after Rebecca was published in Brazil, critic [pt] and other readers pointed out many resemblances to the 1934 book, A Sucessora (The Successor), by Brazilian writer Carolina Nabuco. According to Nabuco and her editor, not only the main plot, but also situations and entire dialogues had been copied.[15] Du Maurier denied having copied Nabuco's book, as did her publisher, pointing out that the plot elements used in Rebecca said to have been plagiarised were quite common.[16]

The controversy was examined in a 6 November 2002 article in The New York Times.[17] The article said that according to Nabuco's memoirs, when the Hitchcock film Rebecca was first shown in Brazil, United Artists wanted Nabuco to sign a document stating that the similarities were merely a coincidence but she refused.[18]

The Times quoted Nabuco's memoirs as saying, "When the film version of 'Rebecca' came to Brazil, the producers' lawyer sought out my lawyer to ask him that I sign a document admitting the possibility of there having been a mere coincidence. I would be compensated with a quantity described as 'of considerable value.' I did not consent, naturally."[17] The Times article said, "Ms. Nabuco had translated her novel into French and sent it to a publisher in Paris, who she learned was also Ms. du Maurier's [publisher] only after Rebecca became a worldwide success. The novels have identical plots and even some identical episodes."[17]

Author Frank Baker believed that du Maurier had plagiarised his novel The Birds (1936) in her short story "The Birds" (1952). Du Maurier had been working as a reader for Baker's publisher Peter Llewelyn Davies at the time he submitted the book.[citation needed] When Hitchcock's The Birds was released in 1963, based on du Maurier's story, Baker considered, but was advised against, pursuing costly litigation against Universal Studios.[19]

Personal life[]

Du Maurier married Major (later Lieutenant-General) Frederick "Boy" Browning in 1932. They had three children:

- Tessa (b. 1933), who married Major Peter de Zulueta. After they divorced, she married David Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, in 1970.

- Flavia (b. 1937), who married Captain Alastair Tower. After they divorced, she married General Sir Peter Leng.

- Christian (b. 1940), a photographer and filmmaker. He married Olive White (Miss Ireland 1961).

Biographers have noted that du Maurier's marriage was at times somewhat chilly and that she could be aloof and distant to her children, especially the girls, when immersed in her writing.[20][21] Her husband died in 1965 and soon after Daphne moved to Kilmarth, near Par, Cornwall, which became the setting for The House on the Strand.

Du Maurier has often been painted as a frostily private recluse who rarely mixed in society or gave interviews.[21] An exception to this came after the release of the film A Bridge Too Far, in which her late husband was portrayed in a less-than-flattering light. Incensed, she wrote to the national newspapers, decrying what she considered unforgivable treatment.[22] Once out of the public spotlight, however, many remembered her as a warm and immensely funny person who was a welcoming hostess to guests at Menabilly,[9] the house which she had leased for many years (from the Rashleigh family) in Cornwall.

She appeared as a castaway in the BBC Radio programme Desert Island Discs broadcast on 3 September 1977. Her chosen book was The Collected Works of Jane Austen, and her luxury was whiskey and ginger ale.[23]

Du Maurier was an early member of Mebyon Kernow, a Cornish nationalist party.[24]

Alleged secret sexual relationships[]

After her death in 1989, writers began spreading stories about her alleged relationships with various people,[20] including actress Gertrude Lawrence, as well as her supposed attraction to Ellen Doubleday, the wife of her U.S. publisher Nelson Doubleday.[21][a] Du Maurier stated in her memoirs that her father had wanted a son;[20] being a tomboy, she wished to have been born a boy.

The Daphne du Maurier Companion, edited by Helen Taylor, includes Taylor's claims that du Maurier confessed to her in 1965 that she had had an incestuous relationship with her father and that he had been a violent alcoholic.[27]

In correspondence that her family released to biographer Margaret Forster, du Maurier explained to a trusted few people her own unique slant on her sexuality: her personality comprised two distinct people – the loving wife and mother (the side she showed to the world); and the lover (a "decidedly male energy") hidden from virtually everyone and the power behind her artistic creativity. According to Forster's biography, du Maurier believed the "male energy" propelled her writing.[28] Forster wrote that du Maurier's denial of her bisexuality unveiled a "homophobic" fear of her true nature.[21]

The children of both du Maurier and Lawrence have objected strongly to the stories about their mothers' alleged intimate relationship. Two years after Lawrence died, a biography of her authored by her widower, Richard Aldrich, went into detail about a friendship between her and du Maurier that had begun in 1948 when Lawrence had accepted the lead role in du Maurier's new play September Tide.[29] Aldrich said that Lawrence had toured Britain in the play in 1948 and continued with it in London's West End theatre district through 1949, and that later du Maurier visited them at their home in the United States.[29] Aldrich made no mention of a possible same-sex relationship.[29]

Death[]

Du Maurier died on 19 April 1989, aged 81, in Cornwall, which had been the setting for many of her books. Her body was cremated and her ashes scattered off the cliffs around Kilmarth and Menabilly, Cornwall.[30][31]

Cultural references[]

- The dialogue of Nikos Nikolaidis' 1987 film Morning Patrol contains excerpts of du Maurier's published works.

- Daphne du Maurier was one of five "Women of Achievement" selected for a set of British stamps issued in August 1996.[32]

- English Heritage caused controversy in June 2008 by denying an application to commemorate her home in Hampstead with a Blue Plaque. In 2011 a plaque was mounted on Cannon Cottage in Well Street, Hampstead, put up by the Heath and Hampstead Society.[33]

- In 2013, grandson Ned Browning released a collection of men's and women's watches based on characters from the novel Rebecca, under the brand name du Maurier Watches.[34]

- In the 2014 novel The House at the End of Hope Street,[35] du Maurier is featured as one of the women who has lived in the titular house.[36]

- The character of Bedelia Du Maurier in the television series Hannibal was named in part after du Maurier because its creator Bryan Fuller is a fan of Alfred Hitchcock, who had adapted three of du Maurier's books to film.[37]

- Daphne du Maurier appears as a character in the short story "The Housekeeper" by Rose Tremain. The story imagines a lesbian affair between du Maurier and a Polish housekeeper, who is then fictionalised as Mrs Danvers in Rebecca.

Publications[]

Fiction[]

Novels[]

- The Loving Spirit (1931)

- (1932)

- (1933) (later re-published as Julius)

- Jamaica Inn (1936)

- Rebecca (1938)

- Frenchman's Creek (1941)

- Hungry Hill (1943)

- The King's General (1946)

- The Parasites (1949)

- My Cousin Rachel (1951)

- Mary Anne (1954)

- The Scapegoat (1957)

- Castle Dor (1961) (with Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch)[38]

- (1963)

- (1965)

- The House on the Strand (1969)

- Rule Britannia (1972)

Plays[]

- Rebecca (1940) (du Maurier's stage adaptation of her novel)

- The Years Between (1945) (play)

- (1948) (play)

Short fiction[]

- Happy Christmas (1940) (short story)

- (1940) (short story collection)

- The Apple Tree (1952) (short story collection); entitled Kiss Me Again, Stranger (1953) in the US, with two additional stories; later republished as The Birds and Other Stories

- Early Stories (1959) (short story collection, stories written between 1927–1930)[39]

- The Breaking Point (1959) (short story collection, AKA The Blue Lenses)

- The Birds and Other Stories (1963) (republication of The Apple Tree)[40]

- Not After Midnight (1971)[41] (story collection); published as Don't Look Now in the US and later also in the UK

- The Rendezvous and Other Stories (1980) (short story collection)

- (1987) (anthology of earlier stories, illustrated by Michael Foreman, AKA Echoes from the Macabre: Selected Stories)

- The Doll: The Lost Short Stories (2011) (collection of early short stories)

Non-fiction[]

- Gerald: A Portrait (1934)

- The du Mauriers (1937)

- The Young George du Maurier: a selection of his letters 1860–67 (1951)

- The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë (1960)

- Vanishing Cornwall (includes photographs by her son Christian, 1967)

- Golden Lads: Sir Francis Bacon, Anthony Bacon and their Friends (1975)

- The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall (1976)

- Growing Pains – the Shaping of a Writer (a.k.a. Myself When Young – the Shaping of a Writer, 1977)

- The Rebecca Notebook and Other Memories (1983)

- Enchanted Cornwall (1989)

See also[]

- The Queen's Book of the Red Cross

- Category:Novels by Daphne du Maurier

- Maroon beret – She was said to have chosen the colour which is now an international symbol of airborne forces, however in a letter, kept by the British Airborne Assault Archive, she wrote that it was untrue.[42]

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Dunn, Jane. Daphne du Maurier and Her Sisters. HarperPress (2013)

- ^ Daphne du Maurier profile by Richard Kelly (essay date 1987), "The World of the Macabre: The Short Stories", Daphne du Maurier, Twayne Publishers, 1987, pp. 123–40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dunn, Jane Daphne du Maurier and her SistersHarperPress (2013)

- ^ Bret, David (1 January 1998). Tallulah Bankhead: a scandalous life. London/Jersey City, NJ: Robson Books; Parkwest Publications. p. 34. ISBN 1861051905. OCLC 40157558.

- ^ "Book About Plants Receives Award: Dr. Fairchild's 'Garden' Work Cited by Booksellers", The New York Times, 15 February 1939, p. 20. ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851-2007).

- ^ "The Big Read", BBC (April 2003). Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Books, Five. "The Best Daphne Du Maurier Books | Five Books Expert Recommendations". Five Books. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Martyn Shallcross, Daphne du Maurier Country, Bossiney Books.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Oriel Malet (ed.), Letters from Menabilly, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1993.

- ^ BBC Interview, 1979.

- ^ Kate Kellaway, The Observer, 15 April 2007. "Daphne's unruly passions", theguardian.com; retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Bell, Matthew (20 February 2011). "Fan tracks down lost stories of Daphne Du Maurier". The Independent. London, UK.

- ^ John Thaxter, "The Years Between", The Stage, 10 September 2007.

- ^ Margaret Forster, Daphne du Maurier, Chatto & Windus, 1993, p. 370, ISBN 0-7011-3699-5

- ^ Nabuco, Carolina (1985), A Sucessora (6 ed.), Art, archived from the original on 2 October 2011

- ^ "Bull's-Eye for Bovarys". Time. 2 February 1942. Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rohter, Larry (6 November 2002). "Tiger in a Lifeboat, Panther in a Lifeboat: A Furor Over a Novel". The New York Times.

- ^ "Rebecca seria brasileira" [Rebecca would be Brazilian]. Os Filmes (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ^ "Biography". UK: Frank Baker. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Conradi, Peter J (1 March 2013). "Women in love: The fantastical world of the du Mauriers". ft.com. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Margaret Forster, Daphne du Maurier: The Secret Life of the Renowned Storyteller, Chatto & Windus.

- ^ Judith Cook, Daphne, Bantam Press.

- ^ "Desert Island Disks: Dame Daphne Du Maurier". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Watts, Andrew (3 June 2017). "Duchy original: Cornish national consciousness gets stronger by the year | The Spectator". The Spectator. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (11 February 2007). "Du Maurier's lesbian loves on film". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ Kregloeon, Karman (21 May 2007). "BBC2's "Daphne" Explores Du Maurier's Bisexuality". AfterEllen. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Helen (2008). The Daphne du Maurier Companion. London: Virago UK. ISBN 978-1844082353.

- ^ Daphne du Maurier, Myself When Young, Victor Gollancz.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Aldrich, Richard (1954). Gertrude Lawrence As Mrs. A. New York: Greystone Press. pp. 307–8.

- ^ Margaret Forster, ‘Du Maurier, Dame Daphne (1907–1989)’, rev., Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 19 Jan 2009

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 13209). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Women of Achievement" (Royal Mail Special Stamps). Accessed 24 June 2017.

- ^ Adrienne Rice. "Daphne du Maurier commemorated in Hampstead - Heritage - Hampstead Highgate Express". Hamhigh.co.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ "Mens Swiss Watch Collection - Luxury Timepieces". du Maurier Watches. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ van, Praag, Menna (2014). The house at the end of Hope Street : a novel. New York. ISBN 978-0143124948. OCLC 852829959.

- ^ THE HOUSE AT THE END OF HOPE STREET by Menna van Praag | Kirkus Reviews.

- ^ VanDerWerff, Emily (26 June 2013). "Bryan Fuller walks us through Hannibal's debut season (part 4 of 4) · The Walkthrough · The A.V. Club". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ du Maurier.org. "Castle Dor". Dumaurier.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ du Maurier.org. "Early Stories". Dumaurier.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ du Maurier.org. "The Birds". Dumaurier.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ du Maurier.org. "Not After Midnight". Dumaurier.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Rebecca Skinner (20 January 2015). British Paratrooper 1940–45. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4728-0514-0.

Further reading and other sources[]

- Kelly, Richard (1987). Daphne du Maurier. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-6931-5.

- Obituary in The Independent 21 April 1989

- Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, London, 1887– : Du Maurier, Dame Daphne (1907–1989); Browning, Sir Frederick Arthur Montague (1896–1965); Frederick, Prince, Duke of York and Albany (1763–1827); Clarke, Mary Anne (1776?–1852).

- Du Maurier, Daphne, Mary Anne, Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, 1954.

- Rance, Nicholas. "Not like Men in Books, Murdering Women: Daphne du Maurier and the Infernal World of Popular Fiction." In Clive Bloom (ed), Creepers: British Horror and Fantasy in the Twentieth Century. London and Boulder CO: Pluto Press, 199, pp. 86–98.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Daphne du Maurier |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daphne du Maurier. |

- Daphne du Maurier at IMDb

- Daphne du Maurier at the British Library

- 1971 BBC TV interview (alternate link)

- Estate representation and published works

- dumaurier.org – extensive news and information site

- Works by or about Daphne du Maurier at Internet Archive

- Daphne du Maurier at University of Exeter Special Collections

- 1907 births

- 1989 deaths

- 20th-century English women writers

- 20th-century English novelists

- Anthony Award winners

- British historical novelists

- British women short story writers

- Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Daughters of knights

- Du Maurier family

- Edgar Award winners

- English horror writers

- English people of French descent

- English short story writers

- English women novelists

- National Book Award winners

- People involved in plagiarism controversies

- Wives of knights

- Women historical novelists

- Women horror writers

- Writers from London

- Writers of Gothic fiction

- Weird fiction writers