Defender (association football)

In the sport of association football, a defender is an outfield player whose primary roles are to stop attacks during the game and prevent the opposing team from scoring goals.

Centre backs are usually in pairs, with two full-backs to their left and right, but can come in threes with no full backs.

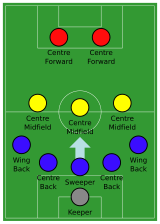

There are four types of defenders: centre-back, sweeper, full-back, and wing-back. The centre-back and full-back positions are essential in most modern formations. The sweeper and wing-back roles are more specialized for certain formations depending on the managers choice of play and adaptation.

Centre-back[]

A centre-back (also known as a central defender or centre-half, as the modern role of the centre-back arose from the centre-half position) defends in the area directly in front of the goal and tries to prevent opposing players, particularly centre-forwards, from scoring. Centre-backs accomplish this by blocking shots, tackling, intercepting passes, contesting headers and marking forwards to discourage the opposing team from passing to them.

With the ball, centre-backs are generally expected to make long and pinpoint passes to their teammates, or to kick unaimed long balls down the field. For example, a clearance is a long unaimed kick intended to move the ball as far as possible from the defender's goal. Due to the many skills centre-backs are required to possess in the modern game, many successful contemporary central-defensive partnerships have involved pairing a more physical defender with a defender who is quicker, more comfortable in possession and capable of playing the ball out from the back; examples of such pairings have included David Luiz, Gary Cahill John Terry and Ricardo Carvalho with Chelsea, Sergio Ramos, Raphaël Varane or Pepe with Real Madrid, Nemanja Vidić and Rio Ferdinand with Manchester United, or Giorgio Chiellini, Leonardo Bonucci, Andrea Barzagli and Medhi Benatia with Juventus.[1][2]

During normal play, centre-backs are unlikely to score goals. However, when their team takes a corner kick or other set pieces, centre-backs may move forward to the opponents' penalty area; if the ball is passed in the air towards a crowd of players near the goal, then the heading ability of a centre-back is useful when trying to score. In this case, other defenders or midfielders will temporarily move into the centre-back positions.

Some centre-backs have also been known for their direct free kicks and powerful shots from distance. Brazilian defenders David Luiz, Alex, and Naldo have been known for using the cannonball free-kick method, which relies more on power than placement.

In the modern game, most teams employ two or three centre-backs in front of the goalkeeper. The 4–2–3–1, 4–3–3, and 4–4–2 formations all use two centre-backs.

There are two main defensive strategies used by centre-backs: the zonal defence, where each centre-back covers a specific area of the pitch; and man-to-man marking, where each centre-back has the job of tracking a particular opposition player. In the now obsolete man–to–man marking systems such as catenaccio, as well as the zona mista strategy that later arose from it, there were often at least two types of centre-backs who played alongside one another: at least one man–to–man marking centre-back, known as the stopper, and a free defender, which was usually known as the sweeper, or libero, whose tasks included sweeping up balls for teammates and also initiating attacks.[3]

Sweeper (libero)[]

The sweeper (or libero) is a more versatile centre-back who "sweeps up" the ball if an opponent manages to breach the defensive line.[4][5] This position is rather more fluid than that of other defenders who man-mark their designated opponents. Because of this, it is sometimes referred to as libero, which is Italian for "free".[6][7]

Austrian manager Karl Rappan is thought to be a pioneer of this role, when he incorporated it into his catenaccio or verrou (also "doorbolt/chain" in French) system with Swiss club Servette during the 1930s, deciding to move one player from midfield to a position behind the defensive line, as a "last man" who would protect the back-line and start attacks again.[8][9] As coach of Switzerland in the 1930s and 1940s, Rappan played a defensive sweeper called the verrouilleur, positioned just ahead of the goalkeeper.[10]

During his time with Soviet club Krylya Sovetov Kuybyshev in the 1940s, Alexander Kuzmich Abramov also used a player similar to a sweeper in his defensive tactic known as the Volzhskaya Zashchepka, or the "Volga Clip." Unlike the verrou, his system was not as flexible, and was a development of the WM rather than the 2–3–5, but it also featured one of the half-backs dropping deep; this allowed the defensive centre-half to sweep in behind the full-backs.[11]

In Italy, the libero position was popularised by Nereo Rocco's and Helenio Herrera's use of catenaccio.[12] The current Italian term for this position, libero, which is thought to have been coined by Gianni Brera, originated from the original Italian description for this role libero da impegni di marcatura (i.e., "free from man-marking tasks");[6][7][13] it was also known as the "battitore libero" ("free hitter," in Italian, i.e. a player who was given the freedom to intervene after their teammates, if a player had gotten past the defence, to clear the ball away).[11][14][15][16][17][18] In Italian football, the libero was usually assigned the number six shirt.[8]

One of the first predecessors of the libero role in Italy was used in the so–called 'vianema' system, a predecessor to catenaccio, which was used by Salernitana during the 1940s. The system originated from an idea that one of the club's players – Antonio Valese – posed to his manager Giuseppe Viani. Viani altered the English WM system – known as the sistema in Italy – by having his centre-half-back retreat into the defensive line to act as an additional defender and mark an opposing centre-forward, instead leaving his full-back (which, at the time, was similar to the modern centre-back role) free to function as what was essentially a sweeper, creating a 1–3–3–3 formation; he occasionally also used a defender in the centre-forward role, and wearing the number nine shirt, to track back and mark the opposing forwards, thus freeing up the full-backs form their marking duties. Andrea Schianchi of La Gazzetta dello Sport notes that this modification was designed to help smaller teams in Italy, as the man–to–man system often put players directly against one another, favouring the larger and wealthier teams with stronger individual players.[19][20][21][22] In Italy, the libero is also retroactively thought to have evolved from the centre-half-back role in the English WM system, or sistema, which was known as the centromediano metodista role in Italian football jargon, due to its association with the metodo system; in the metodo system, however, the "metodista" was given both defensive and creative duties, functioning as both a ball–winner and deep-lying playmaker. Juventus manager Felice Borel used Carlo Parola in the centre-half role, as a player who would drop back into the defence to mark opposing forwards, but also start attacks after winning back possession, in a similar manner to the sweeper, which led to the development of this specialised position.[23][24][25][26][27] Indeed, Herrera's catenaccio strategy with his Grande Inter side saw him withdraw a player from his team's midfield and instead deploy them further-back in defence as a sweeper.[28] Prior to Viani, Ottavio Barbieri is also thought by some pundits to have introduced the sweeper role to Italian football during his time as Genoa's manager. Like Viani, he was influenced by Rappan's verrou, and made several alterations to the English WM system or "sistema", which led to his system being described as mezzosistema. His system used a man-marking back-line, with three man-marking defenders and a full-back who was described as a terzino volante (or vagante, as noted at the time by former footballer and Gazzetta dello Sport journalist Renzo De Vecchi); the latter position was essentially a libero, which was later also used by Viani in his vianema system, and Rocco in his catenaccio system.[29][30][31][32]

Though sweepers may be expected to build counter-attacking moves, and as such require better ball control and passing ability than typical centre-backs, their talents are often confined to the defensive realm. For example, the catenaccio system of play, used in Italian football in the 1960s, often employed a predominantly defensive sweeper who mainly "roamed" around the back line; according to Schianchi, Ivano Blason is considered to be the first true libero in Italy, who – under manager Alfredo Foni with Inter and subsequently Nereo Rocco with Padova – would serve as the last man in his team, positioned deep behind the defensive line, and clearing balls away from the penalty area. Armando Picchi was subsequently also a leading exponent of the more traditional variant of this role in Helenio Herrera's Grande Inter side of the 1960s.[11][19][33][34][35]

The more modern libero possesses the defensive qualities of the typical libero while being able to expose the opposition during counterattacks by carrying or play the ball out from the back.[36] Some sweepers move forward into midfield, and distribute the ball up-field, while others intercept passes and get the ball off the opposition without needing to hurl themselves into tackles. If the sweeper does move up the field to distribute the ball, they will need to make a speedy recovery and run back into their position. In modern football, its usage has been fairly restricted, with few clubs in the biggest leagues using the position.

The modern example of this position is most commonly believed to have been pioneered by Franz Beckenbauer, and subsequently Gaetano Scirea, Morten Olsen and Elías Figueroa, although they were not the first players to play this position. Aside from the aforementioned Blason and Picchi, earlier proponents also included Alexandru Apolzan, Velibor Vasović, and Ján Popluhár.[36][37][38][39][40][41][42] Giorgio Mastropasqua was known for revolutionising the role of the libero in Italy during the 1970s; under his Ternana manager Corrado Viciani, he served as one of the first modern exponents of the position in the country, due to his unique technical characteristics, namely a player who was not only tasked with defending and protecting the back-line, but also advancing out of the defence into midfield and starting attacking plays with their passing after winning back the ball.[14][43] Other defenders who have been described as sweepers include Bobby Moore, Franco Baresi, Ronald Koeman, Fernando Hierro, Miodrag Belodedici, Matthias Sammer, and Aldair, due to their ball skills, vision, and long passing ability.[36][37][38][44] Though it is rarely used in modern football, it remains a highly respected and demanding position.

Recent and successful uses of the sweeper include by Otto Rehhagel, Greece's manager, during UEFA Euro 2004. Rehhagel utilized Traianos Dellas as Greece's sweeper to great success, as Greece became European champions.[45][46][47] For Bayer Leverkusen, Bayern Munich and Inter Milan, Brazilian international Lúcio adopted the sweeper role too, but was also not afraid to travel long distances with the ball, often ending up in the opposition's final third.

Although this position has become largely obsolete in modern football formations, due to the use of zonal marking and the offside trap, certain players such as Daniele De Rossi,[48] Leonardo Bonucci, Javi Martínez and David Luiz have played a similar role as a ball-playing central defender in a 3–5–2 or 3–4–3 formation; in addition to their defensive skills, their technique and ball-playing ability allowed them to advance into midfield after winning back possession, and function as a secondary playmaker for their teams.[48][49]

Some goalkeepers, who are comfortable leaving their goalmouth to intercept and clear through balls, and who generally participate more in play, such as René Higuita, Manuel Neuer, Edwin van der Sar, Fabien Barthez, Marc-André ter Stegen, Bernd Leno and Ederson, among others, have been referred to as sweeper-keepers.[50][51][52]

Full-back[]

The full-backs (the left-back and the right-back) take up the holding wide positions and traditionally stayed in defence at all times, until a set-piece. There is one full-back on each side of the field except in defences with fewer than four players, where there may be no full-backs and instead only centre-backs.[53]

In the early decades of football under the 2–3–5 formation, the two full-backs were essentially the same as modern centre-backs in that they were the last line of defence and usually covered opposing forwards in the middle of the field.[54]

The later 3–2–5 style involved a third dedicated defender, causing the left and right full-backs to occupy wider positions.[55] Later, the adoption of 4–2–4 with another central defender[56] led the wide defenders to play even further over to counteract the opposing wingers and provide support to their own down the flanks, and the position became increasingly specialised for dynamic players who could fulfil that role as opposed to the central defenders who remained fairly static and commonly relied on strength, height and positioning.

In the modern game, full-backs have taken on a more attacking role than was the case traditionally, often overlapping with wingers down the flank.[57] Wingerless formations, such as the diamond 4–4–2 formation, demand the full-back to cover considerable ground up and down the flank. Some of the responsibilities of modern full-backs include:

- Provide a physical obstruction to opposition attacking players by shepherding them towards an area where they exert less influence. They may manoeuvre in a fashion that causes the opponent to cut in towards the centre-back or defensive midfielder with their weaker foot, where they are likely to be dispossessed. Otherwise, jockeying and smart positioning may simply pin back a winger in an area where they are less likely to exert influence.

- Making off-the-ball runs into spaces down the channels and supplying crosses into the opposing penalty box.

- Throw-ins are often assigned to full-backs.

- Marking wingers and other attacking players. Full-backs generally do not commit to challenges in their opponents' half. However, they aim to quickly dispossess attacking players who have already breached the defensive line with a sliding tackle from the side. Markers must, however, avoid keeping too tight on opponents or risk disrupting the defensive organization.[58]

- Maintaining tactical discipline by ensuring other teammates do not overrun the defensive line and inadvertently play an opponent onside.

- Providing a passing option down the flank; for instance, by creating opportunities for sequences like one-two passing moves.

- In wingerless formations, full-backs need to cover the roles of both wingers and full-backs, although defensive work may be shared with one of the central midfielders.

- Additionally, attacking full-backs help to pin both opposition full-backs and wingers deeper in their own half with aggressive attacking intent. Their presence in attack also forces the opposition to withdraw players from central midfield, which the team can seize to its advantage.[59]

Due to the physical and technical demands of their playing position, successful full-backs need a wide range of attributes, which make them suited for adaptation to other roles on the pitch. Many of the game's utility players, who can play in multiple positions on the pitch, are natural full-backs. A rather prominent example is the Real Madrid full-back Sergio Ramos, who has played on the flanks as a full-back and in central defence throughout his career. In the modern game, full-backs often chip in a fair share of assists with their runs down the flank when the team is on a counter-attack. The more common attributes of full-backs, however, include:

- Pace and stamina to handle the demands of covering large distances up and down the flank and outrunning opponents.

- A healthy work rate and team responsibility.

- Marking and tackling abilities and a sense of anticipation.

- Good off-the-ball ability to create attacking opportunities for his team by running into empty channels.

- Dribbling ability. Many of the game's eminent attacking full-backs are excellent dribblers in their own right and occasionally deputize as attacking wingers.

- Player intelligence. As is common for defenders, full-backs need to decide during the flow of play whether to stick close to a winger or maintain a suitable distance. Full-backs that stay too close to attacking players are vulnerable to being pulled out of position and leaving a gap in the defence. A quick passing movement like a pair of one-two passes will leave the channel behind the defending full-back open. This vulnerability is a reason why wingers considered to be dangerous are double-marked by both the full-back and the winger. This allows the full-back to focus on holding his defensive line.[60]

Full-backs rarely score goals, as they often have to stay back to cover for the centre-backs during corner kicks and free kicks, when the centre backs usually go forward to attempt to score from headers. That said, full-backs can sometimes score during counterattacks by running in from the wings, often involving one-two passing moves with midfield players.

Wing-back[]

The wing-back is a variation on the full-back, but with a heavier emphasis on attack. Wing-backs are typically used in a formation with 3 centre-backs and are sometimes classified as midfielders instead of defenders. They can, however, be used in formations with only two centre-backs, such as in Jürgen Klopp's 4–3–3 system that he uses at Liverpool, in which the wing-backs play high up the field to compensate for a lack of width in attack. In the evolution of the modern game, wing-backs are the combination of wingers and full-backs. As such, this position is one of the most physically demanding in modern football. Successful use of wing-backs is one of the main prerequisites for the 3–4–3, 3–5–2 and 5–3–2 formations to function effectively. Wing-backs are often more adventurous than full-backs and are expected to provide width, especially in teams without wingers. A wing-back needs to be of exceptional stamina, be able to provide crosses upfield and defend effectively against opponents' attacks down the flanks. A defensive midfielder may be fielded to cover the advances of wing-backs.[61] It can also be occupied by wingers and side midfielders in a three centre-back formation, as seen by ex-Chelsea and ex-Inter Milan manager Antonio Conte.

See also[]

Association football portal

Association football portal- Association football positions

References[]

- ^ Bagchi, Rob (19 January 2011). "Judges have a blindspot when destroyers like Vidic play a blinder". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Bandini, Paolo (13 June 2016). "Giorgio Chiellini: 'I have a strong temperament but off the pitch I am more serene'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "Soccer positions explained: names, numbers and what they do". bundesliga.com. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ BBC Sports Academy

- ^ Evolution of the Sweeper

- ^ Jump up to: a b "DIZIONARIO DI ITALIANO DALLA A ALLA Z: Battitore". La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Damele, Fulvio (1998). Calcio da manuale. Demetra. p. 104.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fontana, Mattia (7 July 2015). "L'evoluzione del libero: da Picchi a Baresi" (in Italian). Eurosport. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Elbech, Søren Florin. "Background on the Intertoto Cup". Mogiel.net (Pawel Mogielnicki). Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Andy Gray with Jim Drewett. Flat Back Four: The Tactical Game. Macmillan Publishers Ltd, London, 1998.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wilson, Jonathan (2009). Inverting The Pyramid: The History of Soccer Tactics. London: Orion. pp. 159–65. ISBN 978-1-56858-963-3. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "What Nereo Rocco would say about AC Milan and the Azzurri". Calciomercato. 21 November 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Bortolotti, Adalberto. "La Storia del Calcio: Il calcio dalle origini a oggi" (in Italian). Treccani: Enciclopedia dello Sport (2002). Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bedeschi, Stefano (14 July 2018). "Gli eroi in bianconero: Giorgio MASTROPASQUA" (in Italian). Tutto Juve. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "battitóre" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ L'Analisi Linguistica e Letteraria 2011-2. L'Analisi Linguistica e Letteraria : Pubblicazione Semestrale. Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore. 2011. p. 232. ISBN 9788867808625. ISSN 1122-1917. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Falco, Giorgio (2015). Sottofondo italiano. Bari: Laterza Solaris. ISBN 9788858120750. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Veronell, Maurizio (21 December 2016). Caratteri, mentalità e dialettica dei sistemi di gioco nel calcio italiano. Milan: GDS. ISBN 9788867825752. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Andrea Schianchi (2 November 2014). "Nereo Rocco, l'inventore del catenaccio che diventò Paròn d'Europa" (in Italian). La Gazzetta dello Sport. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Nereo Rocco" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ Damiani, Lorenzo. "Gipo Viani, l'inventore del "Vianema" che amava il vizio e scoprì Rivera". Il Giornale (in Italian). Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Chichierchia, Paolo (8 April 2013). "Piccola Storia della Tattica: la nascita del catenaccio, il Vianema e Nereo Rocco, l'Inter di Foni e di Herrera (IV parte)" (in Italian). www.mondopallone.it. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Mario Sconcerti (23 November 2016). "Il volo di Bonucci e la classifica degli 8 migliori difensori italiani di sempre" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Giusto, Antonio (15 March 2010). "C'era una volta il Football - Parola e quella rovesciata IMMORTALE" (in Italian). Goal.com. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Blog: La "Parola" a quella rovesciata: chi era costui?" (in Italian). calciomercato.com. 10 April 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Carlo PAROLA" (in Italian). ilpalloneracconta. 20 September 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Radogna, Fiorenzo (20 December 2018). "Mezzo secolo senza Vittorio Pozzo, il mitico (e discusso) c.t. che cambiò il calcio italiano: Ritiri e regista". Il Corriere della Sera (in Italian). p. 8. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Profilo: Helenio Herrera" (in Italian). UEFA.com. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Storie di schemi: l'evoluzione della tattica" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Genoa: Top 11 All Time" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ cbcsports.com 1962 Chile

- ^ fifa.com Intercontinental Cup 1969

- ^ "La leggenda della Grande Inter" [The legend of the Grande Inter] (in Italian). Inter.it. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Mario Sconcerti (23 November 2016). "Il volo di Bonucci e la classifica degli 8 migliori difensori italiani di sempre" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Aquè, Federico (25 March 2020). "Breve storia del catenaccio" (in Italian). Ultimo Uomo. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "BBC Football - Positions guide: Sweeper". BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 5 January 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Remembering Scirea, Juve's sweeper supreme". FIFA.com. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Franz Beckenbauer Biography". Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Rotting fruit, dying flowers The Guardian

- ^ Czechoslovakia World Cup Hero Jan Popluhar Dies Aged 75 Goal.com

- ^ VELIBOR VASOVIC The Independent

- ^ "Evolution of the Sweeper". Outsideoftheboot.com.

- ^ "Gioco Corto: la Ternana di Corrado Viciani" (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Franchino (detto Franco) BARESI (II)". Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Tosatti, Giorgio (5 July 2004). "La Grecia nel mito del calcio. Con il catenaccio" [Greece in the football legends. With Catenaccio] (in Italian). Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ "Traianos Dellas". BBC Sport. 26 May 2004. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (3 July 2004). "EURO 2004: The stylish Portuguese face Greeks' dark art of defense". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Daniele De Rossi and the strange story of the Libero". forzaitalianfootball. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "L'ANGOLO TATTICO di Juventus-Lazio - Due gol subiti su due lanci di Bonucci: il simbolo di una notte da horror" (in Italian). Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Tim Vickery (10 February 2010). "The Legacy of Rene Higuita" Archived 20 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 11 June 2014

- ^ Early, Ken (8 July 2014). "Manuel Neuer cleans up by being more than a sweeper". The Irish Times. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (13 February 2014). "Tottenham's Hugo Lloris is Premier League's supreme sweeper-keeper". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Football is Coming Home to Die-Hard Translators". Article on the Translation Journal. 1 April 2008. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- ^ "England's Uniforms — Shirt Numbers and Names". Englandfootballonline.com. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Ingle, Sean (15 November 2000). "Knowledge Unlimited: What a refreshing tactic". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Lutz, Walter (11 September 2000). "The 4–2–4 system takes Brazil to two World Cup victories". FIFA. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Pleat, David (6 June 2007). "Fleet-of-foot full-backs carry key to effective attacking". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat explains in a Guardian article how full-backs aid football teams when attacking.

- ^ Pleat, David (18 February 2008). "How Gunners can avoid being pulled apart by Brazilian". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat explains the team effort in marking an attacking player stationed in the outside-wing position.

- ^ Pleat, David (18 May 2006). "How Larsson swung the tie". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat explains how the introductions of Barcelona full-back Juliano Belletti and striker Henrik Larsson in the 2006 UEFA Champions League Final improved Barcelona's presence in wide areas. Belletti eventually scored the winning goal for the final.

- ^ Pleat, David (31 December 2007). "City countered by visitors' Petrov defence". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 December 2008. David Pleat discusses the tactical implications of full-backs and other defenders marking wingers in a Guardian match analysis.

- ^ "Positions guide: Wingback". London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- Association football defenders

- Association football positions

- Association football terminology