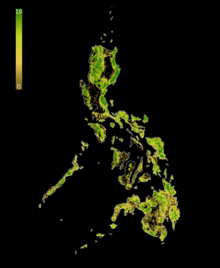

Deforestation in the Philippines

Along with other Southeast Asian countries deforestation in the Philippines is a major environmental issue. Over the course of the 20th century, the forest cover of the country dropped from 70 percent down to 20 percent.[1] Based on an analysis of land use pattern maps and a road map an estimated 9.8 million hectares of forests were lost in the Philippines from 1934 to 1988.[2]

A 2010 land cover mapping by the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) revealed that the total forest cover of the Philippines is 6,839,718 hectares (68,397.18 km2) or 23% of the country's total area of 30,000,000 hectares (300,000 km2).[3]

History[]

Colonial era deforestation[]

It is unknown the percentage of forest the Spaniards found in the Philippines in 1521, before and during the Spanish colonial period, 380 years, some land was cleared for agriculture, roads and cities, and in 1900, more than 70% of the country was still covered by jungles. But after 46 years of American and Japanese occupation, more than 20% of forest was destroyed, and by the end of the 20th century, only 20% of the country was covered by forest.[4]

Forest clearing was notable in the Visayas, particularly in the islands of Negros, Bohol and Cebu, where much of the forest cover had already been lost. Agricultural expansion continued throughout the 20th century.[5]

Deforestation during the martial law era[]

The 1960s and 1970s saw a boom in the logging industry,[6] with the industry reaching its peak during the era of President Ferdinand Marcos.[7]

Under Marcos, logging took on an increasingly central role in the Philippine economy.[8] Following the declaration of martial law in 1972, Marcos handed out concessions to large tracts of land to his senior military officials and cronies. The government encouraged log exportation to Japan resulting from soaring wood demand during Japan's period of rapid economic growth,[9] and pressure to pay foreign debt. Forests resources were exploited by set-up companies and reforestation was rarely undertaken.[6] Japanese log traders purchased massive quantities of cheap logs from unsustainable sources, accelerating deforestation.[10] Log production increased from 6.3 million cubic metres (220×106 cu ft) in 1960 to an average of 10.5 million cubic metres (370×106 cu ft) between 1968 and 1975, peaking at over 15 million cubic metres (530×106 cu ft) in 1975, before declining to about 4 million cubic metres (140×106 cu ft) in 1987.[8] The 1970s and 1980s saw an average of 2.5% of Philippine forests disappearing every year, which was thrice the worldwide deforestation rate.[11]

Deforestation after 1986[]

Deforestation remained very high during the Corazon Aquino and Fidel V. Ramos administrations despite tree-planting efforts due to corruption and inefficiency in the government agencies involved.[6]

Causes[]

Government policies[]

According to scholar Jessica Mathews, short-sighted policies by the Filipino government have contributed to the high rate of deforestation:[12]

The government regularly granted logging concessions of less than ten years. Since it takes 30–35 years for a second-growth forest to mature, loggers had no incentive to replant. Compounding the error, flat royalties encouraged the loggers to remove only the most valuable species. A horrendous 40 percent of the harvestable lumber never left the forests but, having been damaged in the logging, rotted or was burned in place. The unsurprising result of these and related policies is that out of 17 million hectares of closed forests that flourished early in the century only 1.2 million remain today.

Attribution of deforestation to population pressure or agricultural expansion was found not to be backed by existing evidence in a 1992 study.[13] Subsequent research has shown that intensification of existing farmers and improved off-farm income reduced forest pressure.[14] However, in some parts of the country forest encroachment still happens due to high demand for vegetables.[15]

Illegal logging[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (May 2015) |

Illegal logging occurs in the Philippines [16] and intensifies flood damage in some areas.[17]

Conservation efforts[]

Government policies[]

In June 1977, President Ferdinand Marcos signed a law requiring the planting of one tree every month for five consecutive years by every citizen of the Philippines.[18] The law, however, was repealed by President Corazon Aquino in July 1987,[19] with the sole reason that the planting of trees "can be achieved without the compulsion and the penalties for non-compliance therewith as set forth in the Decree".[20]

President Benigno Aquino III established the (NGP)[21] with the signing of Executive Order No. 26 on February 24, 2011.[22] The program aims to increase the country's forest cover in 1.5 million hectares (15,000 km2) of land with 1.5 billion trees from 2011 to 2016. In 2015, the program was expanded to cover all remaining unproductive, denuded and degraded forestlands and its period of implementation extended from 2016 to 2028.[23]

In September 2012, President Benigno Aquino III signed a law requiring all able-bodied citizens of the Philippines, who are at least 12 years of age, to plant one tree every year.[24] Unfortunately, unlike Presidential Decree 1153, there is no provision in the law to enforce and monitor compliance to this requirement.[19]

In May 2019, the House of Representatives of the Philippines has approved House Bill 8728, or the "Graduation Legacy for the Environment Act," principally authored by Magdalo Party-List Representative and Cavite 2nd District Representative Strike Revilla, requiring all graduating elementary, high school, and college students to plant at least 10 trees each before they can graduate.[25] The bill, however, has yet to be signed by the President.[19]

In June 2020, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) started allowing a "family approach" under the National Greening Program, permitting families to establish forest plantations composed of timber and non-timber species which include bamboo and rattan.[26]

Tree planting activities[]

There are tree-planting initiatives conducted in various parts of the country. On March 8, 2012, 1,009,029 mangrove trees were planted within one hour by a team achieved by the joint efforts of Governor Lray Villafuerte of the El Verde Movement and the people of San Rafael of Ragay, Camarines Sur.[27]

On September 26, 2014, the Philippines broke the Guinness World Record for the "Most trees planted simultaneously (multiple locations)", wherein 2,294,629 trees were planted in 29 locations throughout the country by 122,168 participants in an event organized by TreeVolution: Greening MindaNOW (Philippines). Trees planted during the event included rubber, cacao, coffee, timber, mahogany trees, as well as various fruit trees and other species native to the country.[28]

See also[]

- Environmental issues in the Philippines

- Luzon rainforest

References[]

- ^ Lasco, R. D.; R. D. (2001). "Secondary forests in the Philippines: formation and transformation in the 20th century" (PDF). Journal of Tropical Forest Science. 13 (4): 652–670.

- ^ Liu, D; L Iverson; S Brown (1993). "Rates asind patterns of deforestation in the Philippines: application of geographic information system analysis" (PDF). Forest Ecology and Management. 57 (1–4): 1–16. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(93)90158-J. ISSN 0378-1127.

- ^ "County Report; Philippines" (PDF). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. Rome: 4. 2015.

- ^ "Philippine deforestation: A national Spoliarium". Archived from the original on 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Philippine Forests" (PDF). BirdLife. p. 3. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Homer-Dixon, Thomas F. (2010). Environment, Scarcity, and Violence. Princeton University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4008-2299-7. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Inoue, M.; Isozaki, H. (2013). People and Forest — Policy and Local Reality in Southeast Asia, the Russian Far East, and Japan. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-017-2554-5. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ a b Kahl, Colin H. (2006). States, Scarcity, and Civil Strife in the Developing World. Princeton University Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-691-12406-3. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ The Japan Environmental Council (6 December 2012). The State of the Environment in Asia: 2002/2003. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-4-431-67945-5. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Dauvergne, Peter (1997). Shadows in the Forest: Japan and the Politics of Timber in Southeast Asia. MIT Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-262-54087-2. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Dauvergne, Peter (1997). Shadows in the Forest: Japan and the Politics of Timber in Southeast Asia. MIT Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-262-54087-2. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Mathews, Jessica Tuchman (1989). "Redefining Security" (PDF). Foreign Affairs. 68 (2): 162–77. doi:10.2307/20043906. JSTOR 20043906. PMID 12343986.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kummer, D. M. (1992-04-01). "Upland agriculture, the land frontier and forest decline in the Philippines". Agroforestry Systems. 18 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1007/BF00114815. ISSN 1572-9680. S2CID 32324140.

- ^ Shively, Gerald; Pagiola, Stefano (May 2004). "Agricultural intensification, local labor markets, and deforestation in the Philippines". Environment and Development Economics. 9 (2): 241–266. doi:10.1017/S1355770X03001177. ISSN 1355-770X. S2CID 154633988.

- ^ "Averting an agricultural and ecological crisis in the Philippines' salad bowl". Mongabay Environmental News. 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ Teehankee, Julio C. (1993). "The State, Illegal Logging, and Environmental NGOs, in the Philippines". Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies. 9 (1). ISSN 2012-080X.

- ^ "Illegal logging a major factor in flood devastation of Philippines". Terra Daily (AFP). 1 December 2004. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ "Presidential Decree No. 1153, s. 1977". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Pena, Rox (29 August 2019). "Peña: Tree planting requirement for graduation". Sunstar. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 287, s. 1987". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Guarino, Ben (22 January 2020). "The audacious effort to reforest the planet". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 26, s. 2011". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 193, s. 2015". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 12 November 2015. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Republic Act No. 10176". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ "House passes bill requiring graduating students to plant 10 trees on final reading". CNN Philippines. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ De Vera-Ruiz, Ellalyn (23 June 2020). "DENR adopts 'family approach' in National Greening program". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Most mangrove trees planted within one hour (team)". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "Earth Day: Ten incredible environmentally friendly world records". Guinness World Records. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

Further reading[]

- Cavanagh, John; Broad, Robin (1994). Plundering Paradise: The Struggle for the Environment in the Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08921-9.

- Magno, Francisco (April 2001). "Forest Devolution and Social Capital: State-Civil Society Relations in the Philippines". Environmental History. 6 (2): 264–286. doi:10.2307/3985087. JSTOR 3985087. S2CID 73544321.

External links[]

- Philippines Forests at Mongabay

- Illegal logging in the Phililpines

- The Lost Forest at Fieldmuseum.org

- Environmental issues in the Philippines

- Deforestation by region

- Forestry in the Philippines