Diacetyl

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Butane-2,3-dione | |

| Other names

Diacetyl

Biacetyl Dimethyl diketone 2,3-Diketobutane | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 3DMet | |

| 605398 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.428 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2346 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H6O2 | |

| Molar mass | 86.090 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Yellowish green liquid |

| Density | 0.990 g/mL at 15 °C |

| Melting point | −2 to −4 °C (28 to 25 °F; 271 to 269 K) |

| Boiling point | 88 °C (190 °F; 361 K) |

| 200 g/L (20 °C) | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful, flammable |

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements

|

H225, H302, H315, H317, H318, H331, H373 |

| P210, P233, P240, P241, P242, P243, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P272, P280, P301+312, P302+352, P303+361+353, P304+340, P305+351+338, P310, P311, P314, P321, P330, P332+313, P333+313 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

2

3

0 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

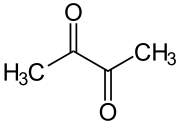

Diacetyl (IUPAC systematic name: butanedione or butane-2,3-dione) is an organic compound with the chemical formula (CH3CO)2. It is a yellow or green liquid with an intensely buttery flavor. It is a vicinal diketone (two C=O groups, side-by-side). Diacetyl occurs naturally in alcoholic beverages and is added to some foods to impart its buttery flavor. Diacetyl is known to cause the lung disease bronchiolitis obliterans in those individuals exposed to it in an occupational setting.[2]

Chemical structure[]

A distinctive feature of diacetyl (and other 1,2-diketones) is the long C–C bond linking the carbonyl centers. This bond distance is about 1.54 Å, compared to 1.45 Å for the corresponding C–C bond in 1,3-butadiene. The elongation is attributed to repulsion between the polarized carbonyl carbon centers.[3]

Occurrence[]

Diacetyl arises naturally as a byproduct of fermentation. In some fermentative bacteria, it is formed via the thiamine pyrophosphate-mediated condensation of pyruvate and acetyl CoA.[4] Sour (cultured) cream, cultured buttermilk, and cultured butter are produced by inoculating pasteurized cream or milk with a lactic starter culture, churning (agitating) and holding the milk until a desired pH drop (or increase in acidity) is attained. Cultured cream, cultured butter, and cultured buttermilk owe their tart flavour to lactic acid bacteria and their buttery aroma and taste to diacetyl.[5]

Production[]

Diacetyl is produced industrially by dehydrogenation of 2,3-butanediol. Acetoin is an intermediate.[6]

Applications[]

In food products[]

Diacetyl and acetoin are two compounds that give butter its characteristic taste. Because of this, manufacturers of artificial butter flavoring, margarines or similar oil-based products typically add diacetyl and acetoin (along with beta-carotene for the yellow color) to make the final product butter-flavored, because it would otherwise be relatively tasteless.[7]

Electronic cigarettes[]

Diacetyl is used as a flavoring agent in some liquids used in electronic cigarettes.[8] and people nearby may be exposed to it in the exhaled aerosol at levels near the limit set for occupational exposure.[9]

In alcoholic beverages[]

At low levels, diacetyl contributes a slipperiness to the feel of the alcoholic beverage in the mouth. As levels increase, it imparts a buttery or butterscotch flavor.[citation needed]

In some styles of beer (e.g. in many beer styles produced in the United Kingdom, such as stouts, English bitters, and Scottish ales), the presence of diacetyl can be acceptable or desirable at low or, in some cases, moderate levels. In other styles, its presence is considered a flaw or undesirable.[10]

Diacetyl is produced during fermentation as a byproduct of valine synthesis, when yeast produces α-acetolactate, which escapes the cell and is spontaneously decarboxylated into diacetyl. The yeast then absorbs the diacetyl, and reduces the ketone groups to form acetoin and 2,3-butanediol.[citation needed]

Beer sometimes undergoes a "diacetyl rest", in which its temperature is raised slightly for two or three days after fermentation is complete, to allow the yeast to absorb the diacetyl it produced earlier in the fermentation cycle. The makers of some wines, such as chardonnay, deliberately promote the production of diacetyl because of the feel and flavor it imparts.[11] Diacetyl is present in some chardonnays known as "butter bombs", although there is a trend back toward the more traditional French styles.[12]

Concentrations from 0.005 mg/L to 1.7 mg/L were measured in chardonnay wines, and the amount needed for the flavor to be noticed is at least 0.2 mg/L.[13][14]

Biochemical toxicity[]

Diacetyl has been shown to alter the amino acid arginine which could interfere with protein structure and function. Additionally diacetyl can bind to DNA and form guanosine adducts which can cause DNA uncoiling and cell death.

The chemical can bypass the blood brain barrier and interfere with cognitive functions, namely causing memory decline in older brains.[citation needed] In vitro studies on human cells also suggest that diacetyl alters the structure and function of the extracellular matrix and modifies epithelial cell responses to growth factors.[15] Human cells exposed to diacetyl also increase secretion of substance P which causes mucus hypersecretion, airway smooth muscle contraction, and edema.[16] Studies in rats have demonstrated significant airway epithelial damage and necrosis after exposure to diacetyl.[15]

Worker safety[]

The United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has suggested diacetyl, when used in artificial butter flavoring (as used in many consumer foods), may be hazardous when heated and inhaled over a long period of time.[17] Workers in several factories that manufacture artificial butter flavoring have been diagnosed with bronchiolitis obliterans, a rare and serious disease of the lungs.[2] As with other end-stage lung diseases, transplantation is currently the most viable treatment option.[18] However, lung transplant rejection is very common and happens to be another setting in which bronchiolitis obliterans is known to occur.[19] The disease has been called "popcorn worker's lung" or "popcorn lung" because it was first seen in former workers of a microwave popcorn factory in Missouri,[20] but NIOSH refers to it by the more general term "flavorings-related lung disease".[20] It has also been called "flavorings-related bronchiolitis obliterans"[20] or diacetyl-induced bronchiolitis obliterans.[21] People who work with flavorings that include diacetyl are at risk for flavorings-related lung disease, including those who work in popcorn factories, restaurants, other snack food factories, bakeries, candy factories, margarine and cooking spread factories, and coffee processing facilities.[22]

In the year 2000 8 cases of bronchiolitis obliterans were detected in former employees of a microwave popcorn plant. Many of these individuals had initially been misdiagnosed as having other pulmonary diseases such as COPD and asthma. NIOSH investigated the worksite and suggested that artificial butter flavoring containing diacetyl was the most likely causative agent for the cases of bronchiolitis obliterans.[23] Follow up investigations at the plant revealed that 25% of employees had abnormal spirometry exams. The plant effectively implemented changes reducing air concentrations of diacetyl by 1 to 3 orders of magnitude in the years following. A stabilization of respiratory symptoms was seen after this point in those who had been exposed to high levels of diacetyl. However, declines in lung function as measured by spirometry continued.[24] Other studies also found cases of bronchiolitis obliterans in workers at 4 other microwave popcorn production facilities.[23] Additionally further studies have demonstrated a large increase in abnormal spirometry values in workers exposed to flavoring chemicals with a clear dose-response relationship.[25][26]

In 2006, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and the United Food and Commercial Workers petitioned the U.S. OSHA to promulgate an emergency temporary standard to protect workers from the deleterious health effects of inhaling diacetyl vapors.[27] The petition was followed by a letter of support signed by more than 30 prominent scientists.[28] The matter is under consideration. On January 21, 2009, OSHA issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking for regulating exposure to diacetyl.[29] The notice requests respondents to provide input regarding adverse health effects, methods to evaluate and monitor exposure, the training of workers. That notice also solicited input regarding exposure and health effects of acetoin, acetaldehyde, acetic acid and furfural.[30]

Two bills in the California Legislature seek to ban the use of diacetyl.[31][32][33]

A 2010 U.S. OSHA Safety and Health Information Bulletin and companion Worker Alert recommend employers use safety measures to avoid exposing employees to the potentially deadly effects of butter flavorings and other flavoring substances containing diacetyl or its substitutes.[34]

A preliminary in vitro study, published in 2012, suggests that diacetyl may exacerbate the effects of beta-amyloid aggregation, a process linked to Alzheimer's disease.[35]

Consumer safety[]

In 2007, the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association recommended reducing diacetyl in butter flavorings.[36] Manufacturers of butter flavored popcorn including Pop Weaver, Trail's End, and ConAgra Foods (maker of Orville Redenbacher's and Act II) began removing diacetyl as an ingredient from their products.[37][38]

In 2012, Wayne Watson, a regular microwavable popcorn consumer for years, was awarded US$7.27 million in damages from a federal jury in Denver, which decided his lung disease was caused by the chemicals in microwave popcorn and that the popcorn's manufacturer, , and the grocery store that sold it should have warned him of its dangers.[39][40][41]

The European Commission has declared diacetyl is legal for use as a flavouring substance in all EU states.[42] As a diketone, diacetyl is included in the EU's flavouring classification Flavouring Group Evaluation 11 (FGE.11). A Scientific Panel of the EU Commission evaluated six flavouring substances (not including diacetyl) from FGE.11 in 2004.[43] As part of this study, the panel reviewed available studies on several other flavourings in FGE.11, including diacetyl. Based on the available data, the panel reiterated the finding that there were no safety concerns for diacetyl's use as a flavouring.[citation needed]

In 2007, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), the EU's food safety regulatory body, stated its scientific panel on food additives and flavourings (AFC) was evaluating diacetyl along with other flavourings as part of a larger study.[44]

In 2016, diacetyl was banned in eliquids / ecigarettes in the EU under the EU Tobacco Products Directive.[45]

See also[]

- Acetylpropionyl, a similar diketone

- Bronchiolitis obliterans

References[]

- ^ Merck Index (11th ed.). p. 2946.

- ^ a b Kreiss, Kathleen (August 2017). "Recognizing occupational effects of diacetyl: What can we learn from this history?". Toxicology. 388: 48–54. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2016.06.009. PMC 5323392. PMID 27326900.

- ^ Eriks K, Hayden TD, Yang SH, Chan IY (1983). "Crystal and molecular structure of biacetyl (2,3-butanedione), (H3CCO)2, at −12 and −100 °C". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105 (12): 3940–3942. doi:10.1021/ja00350a032.

- ^ Speckman RA, Collins EB (January 1968). "Diacetyl biosynthesis in Streptococcus diacetilactis and Leuconostoc citrovorum". Journal of Bacteriology. 95 (1): 174–80. doi:10.1128/JB.95.1.174-180.1968. PMC 251989. PMID 5636815.

- ^ Jay, James M (2000). Modern food microbiology. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen Publishers. pp. 120. ISBN 978-0834216716. OCLC 42692251.

- ^ Siegel H, Eggersdorfer M. "Ketones". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_077.

- ^ Pavia DL. Introduction to Organic Laboratory Techniques (4th ed.). ISBN 978-0-495-28069-9.

- ^ Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, National Academies of Sciences (2018). "Chapter 5: Toxicology of E-Cigarette Constituents". In Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K (eds.). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. National Academies Press. p. 175. ISBN 9780309468343. PMID 29894118.

- ^ Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, National Academies of Sciences (2018). "Chapter 3: E-Cigarette Devices, Uses, and Exposures". In Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K (eds.). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. National Academies Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780309468343. PMID 29894118.

- ^ Janson L (1996). Brew Chem 101. Storey Books. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-0-88266-940-3.

- ^ "Diacetyl". E. coli Metabolome Database. ECMDB. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Trends in Chardonnay". Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards. Retrieved December 2, 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Nielsen JC, Richelieu M (February 1999). "Control of flavor development in wine during and after malolactic fermentation by Oenococcus oeni". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 65 (2): 740–5. doi:10.1128/AEM.65.2.740-745.1999. PMC 91089. PMID 9925610.

- ^ Martineau B, Henick-Kling T, Acree T (1995). "Reassessment of the Influence of Malolactic Fermentation on the Concentration of Diacetyl in Wines". Am. Soc. Enol. Vitic. 46 (3): 385–8.

- ^ a b Brass DM, Palmer SM (August 2017). "Models of toxicity of diacetyl and alternative diones". Toxicology. 388: 15–20. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2017.02.011. PMC 5540796. PMID 28232124.

- ^ Holden VK, Hines SE (March 2016). "Update on flavoring-induced lung disease". Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 22 (2): 158–64. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000250. PMID 26761629. S2CID 23095196.

- ^ "CDC - Flavorings-Related Lung Disease: Exposures to Flavoring Chemicals - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-21. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- ^ Aguilar, Patrick R.; Michelson, Andrew P.; Isakow, Warren (February 2016). "Obliterative Bronchiolitis". Transplantation. 100 (2): 272–283. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000892. ISSN 0041-1337. PMID 26335918. S2CID 26319101.

- ^ Aguilar PR, Michelson AP, Isakow W (February 2016). "Obliterative Bronchiolitis". Transplantation. 100 (2): 272–83. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000892. PMID 26335918. S2CID 26319101.

- ^ a b c Levy BS, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK, eds. (2011). Occupational and environmental health recognizing and preventing disease and injury (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 414. ISBN 9780199750061. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Committee to Review the Respiratory Diseases Research Program, Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2008). Respiratory diseases research at NIOSH : reviews of research programs of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780309118736. Retrieved June 23, 2015.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "CDC - Flavorings-Related Lung Disease: Exposures to Flavoring Chemicals - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Kreiss K (August 2017). "Recognizing occupational effects of diacetyl: What can we learn from this history?". Toxicology. 388: 48–54. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2016.06.009. PMC 5323392. PMID 27326900.

- ^ Kanwal R, Kullman G, Fedan KB, Kreiss K (2011). "Occupational lung disease risk and exposure to butter-flavoring chemicals after implementation of controls at a microwave popcorn plant". Public Health Reports. 126 (4): 480–94. doi:10.1177/003335491112600405. PMC 3115208. PMID 21800743.

- ^ Kreiss K (February 2014). "Work-related spirometric restriction in flavoring manufacturing workers". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 57 (2): 129–37. doi:10.1002/ajim.22282. PMC 4586123. PMID 24265107.

- ^ Lockey JE, Hilbert TJ, Levin LP, Ryan PH, White KL, Borton EK, et al. (July 2009). "Airway obstruction related to diacetyl exposure at microwave popcorn production facilities". The European Respiratory Journal. 34 (1): 63–71. doi:10.1183/09031936.00050808. PMID 19567602.

- ^ "UFCW and Teamsters' Petition to OSHA" (PDF). Defending Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- ^ "Scientists' Letter to Secretary Chao" (PDF). Defending Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- ^ Federal Register, January 21, 2009 issue

- ^ "OSHA begins rule on diacetyl". Chemical & Engineering News. 87 (4): 24. January 26, 2009.

- ^ McKinley J (May 6, 2007). "Flavoring-Factory Illnesses Raise Inquiries". The New York Times.

- ^ "Bill Text - SB-456 Diacetyl". California Legislative Information.

- ^ "Bill Text - AB-514 Workplace safety and health". California Legislative Information.

- ^ OSHA Recommends Safety Measures to Protect Workers from Diacetyl Exposure, EHS Today, December 10, 2010.

- ^ More SS, Vartak AP, Vince R (October 2012). "The butter flavorant, diacetyl, exacerbates β-amyloid cytotoxicity". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 25 (10): 2083–91. doi:10.1021/tx3001016. PMID 22731744.

- ^ "Comments of the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association of the United States on New Information on Butter Flavored Microwave Popcorn" (PDF) (press release). FEMA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ^ Weaver Popcorn Company. Press Release: Pop Weaver introduces first microwave popcorn with flavoring containing no diacetyl Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ConAgra Foods Press Release ConAgra Foods press release announcing removal of added diacetyl

- ^ ABC News: 'Popcorn Lung' Lawsuit Nets $7.2M Award

- ^ NewsFeed Researcher: 'Popcorn Lung' Lawsuit Nets $7.2M Award[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jaffe M (September 21, 2012). "Centennial man with "popcorn lung" disease gets $7.3 million award". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Adopting a register of flavouring substances used in or on foodstuffs drawn up in application of Regulation (EC) No 2232/96 of the European Parliament and of the Council" (PDF). 28 October 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 19, 2007.

- ^ "Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids and Materials in contact with Food (AFC) on a request from the Commission" (PDF). The EFSA Journal. 166: 1–44. 2004.

- ^ Europe takes 'wait-and-see' stance on diacetyl flavouring. Oct 2007

- ^ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - 10 key changes for tobacco products sold in the EU".

Further reading[]

- Harber P, Saechao K, Boomus C (2006). "Diacetyl-induced lung disease". Toxicological Reviews. 25 (4): 261–72. doi:10.2165/00139709-200625040-00006. PMID 17288497. S2CID 42169510.

External links[]

- Toxicology data

- NIOSH Alert: Preventing Lung Disease and Workers who Use or Make Flavorings

- A Case of Regulatory Failure - Popcorn Workers Lung, from www.defendingscience.org.

- Scientists Urge Secretary of Labor to Protect Workers from Diacetyl, a press release from defendingscience.org. Links to studies on the health effects of diacetyl, and to a variety of related documents including the recent OSHA petition and the scientists' letter of support may be found here.

- Flavoring suspected in illness, Washington Post, May 7, 2007.

- NIOSH International Safety Card for 2,3-butanedione

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health - Flavorings-Related Lung Disease

- IFIC - Diacetyl

- Diketones

- Flavors

- Popcorn

- Occupational safety and health

- Conjugated ketones