Dicraeosauridae

| Dicraeosaurids Temporal range: Early Jurassic/Middle Jurassic - Early Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Amargasaurus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Diplodocoidea |

| Clade: | †Flagellicaudata |

| Family: | †Dicraeosauridae Janensch, 1929 |

| Genera | |

| |

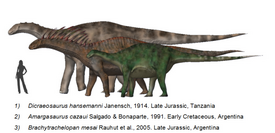

Dicraeosauridae is a family of diplodocoid sauropods who are the sister group to Diplodocidae. Dicraeosaurids are a part of the Flagellicaudata, along with Diplodocidae. Dicraeosauridae includes genera such as Amargasaurus, Suuwassea, Dicraeosaurus, and Brachytrachelopan. Specimens of this family have been found in North America, Asia, Africa, and South America.[1] Their temporal range is from the Early or Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous.[2][3][4] Few dicraeosaurids survived into the Cretaceous, the youngest of which was Amargasaurus.[5]

The group was first described by German paleontologist Werner Janensch in 1914 with the discovery of Dicraeosaurus in Tanzania.[6] Dicraeosauridae are distinct from other sauropods because of their relatively short neck size and small body size.[2]

The clade is monophyletic and well-supported phylogenetically with thirteen unambiguous synapomorphies uniting it.[5] They diverged from Diplodocidae in the Mid-Jurassic, as evidenced by the diversity of dicraeosaurids in both South America and East Africa when Gondwana was still united by land.[5] However, there is some disagreement among paleontologists on the phylogenetic placement of Suuwassea, the only genus of the Dicraeosauridae to be found in North America. It has been characterized as a basal dicraeosaurid by some and a member of the Diplodocidae by others.[5][7] The placement of Suuwassea within Dicraeosauridae or Diplodocidae has substantial biogeographic implications for the evolution of Dicraeosauridae.[8]

Classification[]

Dicraeosaurids are a part of Diplodocoidea and are the sister group to Diploidocidae. In the past two decades, the known diversity of the group has doubled.[5] However, the classification of Suuwassea as a dicraeosaurid is not universally agreed upon.[5][7] Some phylogenetic analyses have found Suuwassea to be a basal diplodocoid instead of a dicraeosaurid.[7] One 2015 analysis has even found Dyslocosaurus as a member of Dicraeosauridae.[9] A 2016 reappraisal of Amargatitanis has placed it into the Dicraeosauridae, as well.[10] In 2018 a new genus, Pilmatueia, was described.[11]

Dicraeosaurids are differentiated from their sister group, diplodocids, and from most sauropods by their relatively small body size and short necks.[12] Dicraeosaurids are advanced sauropods within the monophyletic clade Neosauropoda, which is generally characterized by gigantism. The relatively small body size of dicraeosaurids make them an important outlier relative to other taxa in Neosauropoda.[13]

Phylogeny[]

There have been several different proposed phylogenies of Dicraeosauridae and the intra-group cladistics are not resolved. Suuwassea is variably positioned as either a basal dicraeosaurid or a basal diplodocoid. The most recently published phylogeny by Tschopp et al. (2015) is as follows:[9]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tschopp includes Dyslocosaurus and Dystrophaeus as dicraeosaurids, two genera traditionally not considered to be part of Dicraeosauridae. The specimens of Dystrophaeus viamelae are highly fragmentary, with only a few bones available for study including an ulna, partial scapula, partial dorsal vertebrae, a distal radius, and some metacarpals. Dyslocosaurus polyonychius also has extremely limited fossil evidence that only includes appendicular elements, and the position of it in Tschopp's phylogeny is therefore considered "preliminary".[9]

Several studies, however, do not include even Suuwassea in Dicraeosauridae, such as Sereno et al. (2007);[12] and JD Harris (2006).[8] Other studies, however, recover Suuwassea as a basal dicraeosaurid, including Whitlock (2010)[5] and Salgado et al. (2006).[14]

Paleobiology[]

Feeding behavior[]

As sauropods, dicraeosaurids are obligate herbivores. Due to their relatively small necks and skull shape, it has been deduced that dicraeosaurids and diplodocids primarily browsed close to the ground or at mid height.[5][12] Among the dicraeosurids, only Dicraeosaurus has well-preserved dentition. This makes it difficult for paleontologists to make definitive statements about Dicraeosauridae feeding behavior compared to diplodocid feeding behavior.[15] However, compared to its known relatives, Dicraeosaurus is unique in that it has an equal number of teeth in the upper and lower jaw, though teeth in the lower jaw are replaced more slowly.[15]

Anatomy[]

Dicraeosaurids are characterized by their relatively small body size, short necks, and long neural spines.[16] They are 10–13 meters in body length.[16] They share thirteen unambiguous synapomorphies including dorsal vertebrae without pleurocoels, the presence of a ventrally directed prong on the squamosal, and a subtriangular-shaped dentary symphysis.[5]

Distribution and evolution[]

Dicraeosaurid specimens have been found in three continents - Africa, South America, and North America. The distribution of species is primarily Gondwonan, with the exception of the North American Suuwassea. The presence of Suuwassea in North America is unique among dicraeosaurids, therefore making the proper taxonomic classification of Suuwassea essential. The group likely first diverged from the diplodocids in the middle Jurassic in North America and subsequently dispersed into Gondwana, with the most diversity in East Africa and South America.[5] Amargasaurus was the latest surviving dicraeosaurid genus, living into the Early Cretaceous period.[5]

Timeline of genera descriptions[]

Sources[]

- ^ Gallina, Pablo A.; Apesteguía, Sebastián; Haluza, Alejandro; Canale, Juan I. (2014-05-14). "A Diplodocid Sauropod Survivor from the Early Cretaceous of South America". PLOS ONE. 9 (5): e97128. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...997128G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097128. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4020797. PMID 24828328.

- ^ a b Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Remes, Kristian; Fechner, Regina; Cladera, Gerardo; Puerta, Pablo (2005-06-02). "Discovery of a short-necked sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period of Patagonia". Nature. 435 (7042): 670–672. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..670R. doi:10.1038/nature03623. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15931221. S2CID 4385136.

- ^ Carabajal, Ariana Paulina; Carballido, José L.; Currie, Philip J. (2014-06-07). "Braincase, neuroanatomy, and neck posture of Amargasaurus cazaui (Sauropoda, Dicraeosauridae) and its implications for understanding head posture in sauropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (4): 870–882. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.838174. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 85748606.

- ^ Xing Xu; Paul Upchurch; Philip D. Mannion; Paul M. Barrett; Omar R. Regalado-Fernandez; Jinyou Mo; Jinfu Ma; Hongan Liu (2018). "A new Middle Jurassic diplodocoid suggests an earlier dispersal and diversification of sauropod dinosaurs". Nature Communications. 9 (1): Article number 2700. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.2700X. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05128-1. PMC 6057878. PMID 30042444.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Whitlock, John A. (2011-04-01). "A phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocoidea (Saurischia: Sauropoda)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (4): 872–915. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00665.x. ISSN 1096-3642.

- ^ Weishampel, DB; Dodson, P; Osmolska, H (2007). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520254084.

- ^ a b c Woodruff, D. Cary; Fowler, Denver W. (2012-07-01). "Ontogenetic influence on neural spine bifurcation in Diplodocoidea (Dinosauria: Sauropoda): a critical phylogenetic character". Journal of Morphology. 273 (7): 754–764. doi:10.1002/jmor.20021. ISSN 1097-4687. PMID 22460982. S2CID 206091560.

- ^ a b Harris, Jerald D. (2006-01-01). "The significance of Suuwassea emilieae (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) for flagellicaudatan intrarelationships and evolution". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001805. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 9646734.

- ^ a b c Tschopp, Emanuel; Mateus, Octávio; Benson, Roger B.J. (2015-04-07). "A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". PeerJ. 3: e857. doi:10.7717/peerj.857. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4393826. PMID 25870766.

- ^ Gallina, Pablo Ariel (2016-09-01). "Reappraisal of the Early Cretaceous sauropod dinosaur Amargatitanis macni (Apesteguía, 2007), from northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 64: 79–87. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.04.002.

- ^ Coria, Rodolfo A; Windholtz, Guillermo J; Ortega, Francisco; Currie, Philip J (2018). "A new dicraeosaurid sauropod from the Lower Cretaceous (Mulichinco Formation, Valanginian, Neuquén Basin) of Argentina". Cretaceous Research. 93: 33–48. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.08.019.

- ^ a b c Sereno, Paul C.; Wilson, Jeffrey A.; Witmer, Lawrence M.; Whitlock, John A.; Maga, Abdoulaye; Ide, Oumarou; Rowe, Timothy A. (2007-11-21). "Structural Extremes in a Cretaceous Dinosaur". PLOS ONE. 2 (11): e1230. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1230S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001230. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2077925. PMID 18030355.

- ^ Sander, P. Martin; Christian, Andreas; Clauss, Marcus; Fechner, Regina; Gee, Carole T.; Griebeler, Eva-Maria; Gunga, Hanns-Christian; Hummel, Jürgen; Mallison, Heinrich (2011-02-01). "Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: the evolution of gigantism". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 86 (1): 117–155. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00137.x. ISSN 1469-185X. PMC 3045712. PMID 21251189.

- ^ Salgado, Leonardo; Carvalho, Ismar de Souza; Garrido, Alberto C. (2006). "Zapalasaurus bonapartei, un nuevo dinosaurio saurópodo de La Formación La Amarga (Cretácico Inferior), noroeste de Patagonia, Provincia de Neuquén, Argentina". Geobios. 39 (5): 695–707. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2005.06.001.

- ^ a b Schwarz, Daniela; Kosch, Jens C. D.; Fritsch, Guido; Hildebrandt, Thomas (2015-11-02). "Dentition and tooth replacement of Dicraeosaurus hansemanni (Dinosauria, Sauropoda, Diplodocoidea) from the Tendaguru Formation of Tanzania". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (6): e1008134. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1008134. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 85579166.

- ^ a b Daniela Schwarz-Wings, 10th Annual Meeting of the European Association of Vertebrate Paleontologists. Royo-Torres, R, Gascó, F, and Alcalá, L., coord. ¡Fundamental! 20: 1-290. 2012.

- Diplodocoids

- Dicraeosaurids

- Early Jurassic first appearances

- Early Jurassic taxonomic families

- Late Jurassic taxonomic families

- Early Cretaceous taxonomic families

- Early Cretaceous extinctions

- Prehistoric dinosaur families