Dime Mystery Magazine

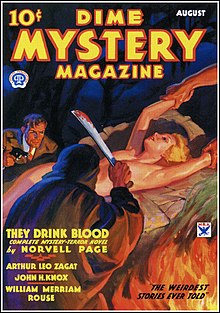

Dime Mystery Magazine was an American pulp magazine that was published from 1932 to 1950. It was the first terror fiction pulp magazine, and was the instigator of a trend in pulp fiction that came to be called weird menace fiction, in which the protagonist struggles against something that appears to be supernatural, but ultimately can be explained in everyday terms. Initially Dime Mystery contained ordinary mystery stories, but with the October 1933 issue it began publishing terror fiction. The publisher, Harry Steeger, later said he was inspired to create the new genre by the Grand Guignol theater in Paris. In 1938 it returned to detective stories once again. The stories occasionally included science fiction elements, such as robots, and drugs that can alter the flow of time. In 1950 it briefly changed its title to 15 Mystery, but ceased publication at the end of that year.[1][2]

Publishing history[]

In 1930, Harry Steeger and Harold Goldsmith set up a pulp magazine publishing company, Popular Publications.[3] The pulp market at the time was changing focus, with detective stories becoming more popular, so two of the first four magazines launched by Popular were in the detective genre: and . These were followed in 1932 by , which quickly became one of Popular's most successful pulps, focusing on lurid crimes. Dime Mystery Book Magazine was begun at the end of 1932 as a sister magazine to Dime Detective, with a novel in each issue.[4] The new magazine struggled,[5] but rather than cancel it, Steeger decided to change it to focus more on horror.[4] The lead novel was eliminated, and replaced with a story of no more than half novel length, allowing more fiction to be included.[4]

The new policy, which began with the October 1933 issue, was a success,[1][6] and the magazine stayed on a monthly schedule for the next seven years.[1] Popular soon launched more titles in the same genre, which has since become known as "weird menace" fiction; the first was Terror Tales, launched in September 1934; it was followed by Horror Stories, in January 1935.[6][7][8] Popular's competitors were not far behind, with Thrilling Mystery appearing in October 1935 from Thrilling Publications.[6][9]

In a 1977 interview, Steeger recalled paying between three-quarters of a cent and a cent per word for fiction during the 1930s, although there were a handful of authors such as Erle Stanley Gardner who could command higher rates. The rate increased in the 1940s, going up by at least a half cent per word, and more in some cases and for some writers.[10] The schedule changed from monthly to bimonthly starting in early 1941.[11] World War II brought paper shortages, but Steeger recalled that the effect was to increase the percentage of each print run that sold, and as a result Popular's sales were higher than at any other time in the company's life.[12]

Contents and reception[]

For the first year, Dime Mystery focused on straightforward detective and mystery fiction.[5] The title was initially Dime Mystery Book Magazine,[11] and the selling point was "A New $2.00 Detective Novel", as the cover declared, complete in each issue.[5] The cover art reinforced this message by depicting a hardcover book, with the detective or mystery scene painted as the cover of the book. Dime Mystery competed with two existing magazines that also published a complete novel in each issue: and .[5] Both were published by Fiction House, and although both cost twice as much as Dime Mystery, at 20 cents, they were well-established, with stories by well-known writers such as Edgar Wallace and Ellery Queen,[5] while Dime Mystery's fiction was "slow, boring and unpopular", in the opinion of pulp historian Jess Nevins.[6]

Rather than giving up on the magazine, which would have meant losing its second-class mailing permit, Steeger decided to change its focus to horror. In a later recollection, Steeger said he was inspired by the Grand Guignol Theater in Paris, which provided gory dramatizations of murder, and torture. The new policy took effect with the October 1933 issue. There were no more complete novels; the word "Book" had already been dropped from the title two issues earlier,[1][11] and the editor, Rogers Terrill now wanted lead stories no longer than about thirty-five thousand words, instead of about fifty-five thousand words.[4] Terrill had a novel he wanted to use, but it had been written for the old policy, and needed to be cut down from sixty thousand words in only a few days. The author mentioned his predicament to Norvell Page, a fast and prolific pulp writer, and Page produced a thirty-five thousand word novel, "Dance of the Skeletons", for Terrill by the deadline.[4] Along with terror and mystery, Terrill insisted on a mundane explanation for the mysterious events in the story. The plot of "Dance of the Skeletons" satisfied all three requirements: Wall Street financiers are disappearing, and their skeletons, stripped of flesh, mysteriously appear on the streets of Manhattan. The explanation is that the villain in the story is killing key businessmen to depress stock prices, and to distract attention from his financial operations he gives the bodies to piranhas. The piranhas reduce the corpses to skeletons, which are secretly left on the city streets.[4]

Terrill gave his authors a working definition of the terms he was using: "Horror is what a girl would feel if, from a safe distance, she watched the ghoul practice diabolical rites upon a victim. Terror is what the girl would feel if, on a dark night, she heard the steps of the ghoul coming toward here and knew she was marked for the next victim. Mystery is the girl wondering who done it and why."[4]

| Issue data for Dime Mystery Magazine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 1932 | 1/1 | |||||||||||

| 1933 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 4/1 |

| 1934 | 4/2 | 4/3 | 4/4 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | 7/1 |

| 1935 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 7/4 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | 8/4 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 9/4 | 10/1 |

| 1935 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 10/4 | 11/1 | 11/2 | 11/3 | 11/4 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | 12/4 | 13/1 |

| 1937 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 13/4 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | 14/4 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 15/4 | 16/1 |

| 1938 | 16/2 | 16/3 | 16/4 | 17/1 | 17/2 | 17/3 | 17/4 | 18/1 | 18/2 | 18/3 | 18/4 | 19/1 |

| 1939 | 19/2 | 19/3 | 19/4 | 20/1 | 20/2 | 20/3 | 20/4 | 21/1 | 21/2 | 21/3 | 21/4 | 22/1 |

| 1940 | 22/2 | 22/3 | 22/4 | 23/1 | 23/2 | 23/3 | 23/4 | 24/1 | 24/2 | 24/3 | 24/4 | |

| 1941 | 25/1 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 25/4 | 26/1 | 26/2 | 26/3 | |||||

| 1942 | 26/4 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/3 | 27/4 | 28/1 | ||||||

| 1943 | 28/3 | 28/3 | 28/4 | 29/1 | 29/2 | 29/3 | ||||||

| 1944 | 29/4 | 30/1 | 30/2 | 30/3 | 30/4 | 31/1 | ||||||

| 1945 | 31/2 | 31/3 | 31/4 | 32/1 | 322/2 | 32/3 | ||||||

| 1946 | 32/4 | 33/1 | 33/2 | 33/3 | 33/4 | 34/1 | ||||||

| 1947 | 34/2 | 34/3 | 34/4 | 35/1 | 35/2 | 35/3 | 35/4 | 36/1 | ||||

| 1948 | 36/2 | 36/3 | 36/4 | 37/1 | 37/2 | 37/3 | 37/4 | |||||

| 1949 | 38/1 | 38/2 | 38/3 | 38/4 | 39/1 | 39/2 | ||||||

| 1950 | 39/3 | 39/4 | 40/1 | 40/2 | 40/3 | |||||||

| Issues of Dime Mystery Magazine, showing volume and issue number. The sequence of editors is not well-documented.[13] | ||||||||||||

This was the start of what became known as the "weird menace" genre.[1] An article by Richard Tooker in the writers' magazine described the requirements of weird menace stories later in the decade: "A fearful menace, apparently due to supernatural agencies, must terrify the characters (and reader, but not the writer) at the start, but the climax must demonstrate convincingly that the menace was natural after all".[4] The stories grew more extreme over time, and the monsters and perils more bizarre and more deadly. Pulp historian Robert Jones quotes a typical description of a monster: "Grey-green was the face, with hollow cheeks and lank, lean jaws. The lips were red with blood, as if the teeth they hid had crunched on unmentionable things. But the eyes—dear God, the eyes—were bottomless pits of darkness, from whose stygian depths Death peered and leered". The cover art for the magazine took full advantage of the new policy, with the heroines depicted in every possible kind of danger.[4] The covers during the weird menace phase were all painted by Walter M. Baumhofer until 1936, with interior art contributed by .[2][11] Baumhofer was succeeded by Tom Lovell for 1936 and much of 1937,[2][14] and Sewell by , David Berger, and Ralph Carlson.[2]

Although most of the fiction was low-quality pulp writing, magazine historian Michael Cook singles out three authors as having produced worthwhile stories for the magazine: , Hugh B. Cave, and Wyatt Blassingame, whom Cook describes as "the most consistently satisfying" weird menace writer.[2] Jones lists "The Corpse-Maker", from the November 1933 issue, as one of Cave's best stories: "A criminal who was horribly disfigured when making his escape from prison...directs the murder of the jurors who convicted him. The are brought to him to be tortured to death."[15]

Blassingame began selling to the pulps in 1933, and wrote an article for the trade press about how to plot a weird menace story. He listed the two plot devices he used: in the first, the hero is pursued by the villain, and repeatedly fails to escape, finally overcoming the villain when all seems lost; in the second, the hero is trapped and menaced on all sides, and must escape. Jones gives two examples of the way Blassingame would vary these basic plots. In "Three Hours to Live", which appeared in the October 1934 Dime Mystery, the hero's family is cursed, and his relatives die, each death preceded by a mysterious bumping noise. When the curse is about to strike, a friend intervenes to reveal that the curse is actually the hero's uncle, who was killing off other family members to get their money. The second plot device is used in Blassingame's "The Black Pit", from the June 1934 Dime Mystery. The hero visits a deserted house and finds a girl there, and the two are attacked by a dangerous escapee from an asylum, who batters down doors to get at them, and climbs down the chimney when foiled. The hero finally manages to kill the attacker by pushing him into a pit.[16]

In 1937, the weird menace magazines as a whole began to feature more sexual images and more sadistic villains. Jones cites Russell Gray's "Burn—Lovely Lady!" as an example of the "sex-sadistic phase" of the genre. It appeared in the June 1938 Dime Mystery, and featured a young married couple being tortured. The wife must agree to endure the pain for two hours to win their freedom: needles are inserted in her breast and "other tender parts of her body", and she is stretched on a rack, and woken by drugs when she faints.[17]

During the weird menace period, the stories were a mixture of mystery and horror, but the protagonist was never a detective. In October 1938 the policy changed again, this time to detective stories with a horror element. The detectives frequently had unusual problems or disabilities: one had hemophilia and had to avoid even the slightest scratch; another was an insomniac when working on a mystery; another was deaf and had to lip-read; another was an amnesiac.[2][18] There was a brief return to weird menace stories in the 1940s.[2]

Bibliographic details[]

Dime Mystery Magazine was published by Popular Publications, and produced 158 issues between December 1932 and October 1950. It was pulp format for all issues; the page count varied between 128 and 144 pages. The price began at 10 cents, increased to 15 cents in November 1944, to 20 cents in December 1948, and finally to 25 cents in February 1950. The title began as Dime Mystery Book Magazine and changed to Dime Mystery Magazine in July 1933; it stayed under that title until 1950 when it changed to 15 Mystery Stories for the last five issues. The volume numbering was completely regular, with each volume having four issues; the final issue was volume 40, number 3. It began as a monthly magazine, and stayed on that schedule till March 1941, omitting only the June 1940 issue. From March 1941 to September 1947 it was bimonthly, except that in 1946 a February issue appeared instead of a March issue. A brief monthly sequence ran from September 1947 until February 1948, followed by another bimonthly sequence that lasted to the end of the run.[19]

The sequence of editors is not well-documented. Pulp historian Robert Kenneth Jones lists Rogers Terrill as the first editor, with the editorship passed to Chandler H. Whipple in about 1941, and Loring Dowst in about 1943;[2] he also lists Henry Sperry as an editor, with Leon Byrne as associate editor: he does not give dates, but notes that both Sperry and Byrne died in 1939.[20] Bibliographer Phil Stephensen-Payne gives the sequence of editors as Rogers Terrill, Henry Sperry, Leon Byrne, Chandler H. Whipple, and Loring Dowst, but gives no dates for the transitions.[21] Pulp historian Robert Weinberg lists Terrill as the editor of all the weird menace issues, from October 1933 to September 1938.[22]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e Ashley (1985a), pp. 180-183.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jones (1983), pp. 170-173.

- ^ Hulse (2013), p. 276.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jones (1975), pp. 3-11.

- ^ a b c d e Weinberg (1981), pp. 372-373.

- ^ a b c d Nevins (2020), p. 42.

- ^ Ashley (1985b), pp. 326-328.

- ^ Ashley (1985c), pp. 660-661.

- ^ Ashley (1985d), pp. 666-667.

- ^ Hardin (1977), pp. 10-11.

- ^ a b c d Stephensen-Payne, Phil (January 6, 2022). "Dime Mystery Magazine". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on 2006-11-04. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ Hardin (1977), p.14.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (February 17, 2022). "Dime Mystery Magazine". Galactic Central. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (February 26, 2022). "Magazines, Listed by Title: Dime Mystery Magazine". Galactic Central. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Jones (1975), pp. 43-44.

- ^ Jones (1975), 51-54.

- ^ Jones (1975), p. 125.

- ^ Weinberg (1981), p. 383.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (January 2, 2022). "Dime Mystery Magazine". Galactic Central. Archived from the original on 2006-11-04. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Jones (1975), p. 23.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil (February 17, 2022). "Magazine Data File: Dime Mystery Magazine". Galactic Central. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Weinberg (1981), pp. 374, 388.

Sources[]

- Ashley, Mike (1985a). "Dime Mystery Magazine". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 180–183. ISBN 0-3132-1221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (1985b). "Horror Stories (1935-1941)". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 326–328. ISBN 0-3132-1221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (1985c). "Terror Tales". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 660–661. ISBN 0-3132-1221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (1985d). "Thrilling Mystery". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (eds.). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 666–667. ISBN 0-3132-1221-X.

- Hardin, Nils (July 1977). "An Interview with Henry Steeger". Xenophile (33): 3–18.

- Hulse, Ed (2013). The Blood'n'Thunder Guide to Pulp Fiction. Murania Press. ISBN 978-1491010938.

- Jones, Robert Kenneth (1975). The Shudder Pulps. West Linn, Oregon: FAX Collector's Editions. ISBN 0-913960-04-7.

- Jones, Robert Kenneth (1983). "Dime Mystery Book". In Cook, Michael L. (ed.). Mystery, Detective, and Espionage Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 170–173. ISBN 0-313-23310-1.

- Nevins, Jess (2020). Horror Fiction in the 20th Century: Exploring Literature's Most Chilling Genre. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440862069.

- Weinberg, Robert (1981). "The Horror Pulps: 1933-1940". In Tymn, Marshall B. (ed.). Horror Literature: A Core Collection and Reference Guide. New York: R.R. Bowker Company. pp. 370–397. ISBN 0-8352-1341-2.

- Magazines established in 1932

- Magazines disestablished in 1950

- Magazines published in New York City