Diplomacy and commerce during the Ming treasure voyages

The Ming treasure voyages had a diplomatic as well as a commercial aspect.[1]

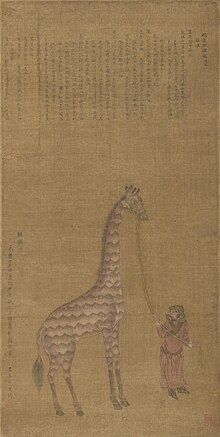

The treasure ships had an enormous cargo of various products.[2] Admiral Zheng returned to China with many kinds of tribute goods, such as silver, spices, sandalwood, precious stones, ivory, ebony, camphor, tin, deer hides, coral, kingfisher feathers, tortoise shells, gums and resin, rhinoceros horn, sapanwood and safflower (for dyes and drugs), Indian cotton cloth, and ambergris (for perfume).[2] They even brought back exotic animals, such as ostriches, elephants, and giraffes.[2] The imports from the voyages provided the large quantities of economic goods that fueled China's own industries.[3] There was so much cobalt oxide from Persia that the porcelain center Jingdezhen had a plentiful supply for decades after the voyages.[2] The fleet also returned with such a large amount of black pepper that the once-costly luxury became a common commodity in Chinese society.[2] There were sometimes so many Chinese goods unloaded into an Indian port that it could take months to price everything.[4][5] The treasure voyages resulted in a flourishing Ming economy,[6] while boosting the lucrative maritime commerce to an all-time high.[7] The voyages also induced a sudden supply shock in the Eurasian market, where the Chinese maritime exploits in Asia led to disruptions of European imports with sudden price spikes in the early 15th century.[8]

The commodities that the ships carried included three major categories: gifts to be bestowed on rulers, items for exchange of goods or payment of goods with fixed prices at low rates (e.g. gold, silver, copper coins, and paper money), and items in which China had the monopoly (e.g. musks, ceramics, and silks).[9] However, the Ming trade enterprise also saw significant changes and developments in which the Chinese themselves began trading and supplying the commodities that were non-Chinese in origin and earlier entirely in the hands of the Indians, Arabs, and other foreigners.[9] For instance, they shipped Southeast Asian sandalwood and Indian pepper to Aden and Dhofar, Indian putchuk and pepper to Hormuz, sandalwood and rice to Mogadishu, and iron cauldrons and pans to Mecca.[9] This highlighted the commercial character of the voyages, in which the Chinese further expanded upon the already large profits from their trade.[9]

The impact of the Ming expeditions on commerce was on multiple levels: it established imperial control over local private commercial networks, expanded tributary relations and thereby brought commerce under state supervision, established court-supervised transactions at foreign ports and thereby generate substantial revenue for both parties, and increased production and circulation of commodities across the region.[10]

Imperial proclamations were issued to the foreign kings, which meant that they could either submit and be bestowed with rewards or refuse and be pacified under the threat of an overwhelming military force.[11][12] Foreign kings had to reaffirm their recognition of the Chinese emperor's superior status by presenting tribute.[13] Many countries were enrolled as tributaries.[14] The treasure fleet conducted the transport of the many foreign envoys to China and back, but some envoys traveled independently.[15] Those rulers who submitted received political protection and material rewards.[16]

During the Hongwu reign, the situation in the Malay-Indonesian world was viewed with a negative attitude.[17] However, the treasure fleet came to dominate the Malay-Indonesian sphere via Java, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula.[17] In Ceylon and southern India, the treasure fleet forced the political situation of the region into their favor, while making the maritime routes safe for commerce and diplomacy.[17]

Overview[]

In Malacca, the Chinese actively sought to develop a commercial hub and a base of operation for the voyages into the Indian Ocean.[18] Malacca had been a relatively insignificant region, not even qualifying as a polity prior to the voyages according to both Ma Huan and Fei Xin, and was a vassal region of Siam.[18] In 1405, the Ming court dispatched Zheng He with a stone tablet enfeoffing the Western Mountain of Malacca as well as an imperial order elevating the status of the port to a country.[18] The Chinese also established a government depot (官廠) as a fortified cantonment for their soldiers.[18] It served as a storage facility as the fleet traveled and assembled from other destinations within the maritime region.[19] Ma Huan reports that Siam did not dare to invade Malacca thereafter.[18] The rulers of Malacca, such as King Paramesvara in 1411, would pay tribute to the Chinese emperor in person.[18] In 1431, when a Malaccan representative complained that Siam was obstructing tribute missions to the Ming court, the Xuande Emperor dispatched Zheng He carrying a threatening message for the Siamese king saying "You, king should respect my orders, develop good relations with your neighbours, examine and instruct your subordinates and not act recklessly or aggressively."[18]

In 1404, the eunuch envoy Yin Qing was sent on a mission from Ming China to Malacca.[20] King Paramesvara of Malacca (r. 1399–1413), delighted by this, reciprocated with an envoy bearing tribute in local products.[20] A year later during the first treasure voyage, Admiral Zheng He arrived at Malacca to formally confer Paramesvara's investiture as King of Malacca.[20] Malacca's ruling house would be on friendly terms with Ming China and collaborate with the treasure fleet.[20] The Ming recognition and alliance was a factor that ensured stability in Malacca.[21] Malacca prospered and gradually came to replace Palembang as the regional trading center.[22]

The Taizong Shilu entry of 12 August 1406 noted that Chen Zuyi and Liang Daoming sent envoys to the Ming court, possibly while Admiral Zheng He was commanding the treasure fleet through Indonesian waters to return home.[23] Chen Zuyi sent his son Chen Shiliang to the Ming court.[23] Liang Daoming sent his nephew Liang Guanzheng, Xigandaliye, and Hajji Muhammad to the Ming court.[23] The Ming court understood that Liang Daoming was the leader of the Chinese community at Palembang, but ranked Chen Zuyi above Liang as they saw Chen as the Chieftain (toumu) of Palembang, which was not an official Ming title.[23] It is possible that Chen Zuyi had hoped for official recognition by the Ming court, but it never came to be.[23] Admiral Zheng He was informed by Shi Jinqing about Chen Zuyi's piracy, causing Chen to be classified as a pirate in the eyes of the Chinese authorities.[24] During the first voyage, Admiral Zheng He established order in Palembang under Chinese rule.[25] The Ming court recognized Shi Jinqing as the Grand Chieftain (da toumu) of Palembang after Admiral Zheng He had captured Chen Zuyi.[26] After Shi Jinqing's death, his daughter Shi Erjie became king (wang)—a title normally not held by women—rather than his son, a very uncommon situation for both the patriarchal Chinese and Muslims.[26]

On 27 February 1425, according to the Taizong Shilu, Admiral Zheng He was sent on a diplomatic mission to confer a gauze cap, a ceremonial robe (with floral gold woven into gold patterns in the silk), and a silver seal on Shi Jisun (Shi Jinqing's son), who had received the Yongle Emperor's approval to succeed his father's office of Pacification Commissioner.[27] The Taizong Shilu didn't define Palembang as a separate country on its own right.[28] In contemporary Chinese sources, Palembang was mostly known as Jiugang (lit. "Old Harbor").[25]

During the second voyage, the rulers of Calicut, Malacca, and Champa had made it a policy to cooperate with Ming China and gave the treasure fleet a series of bases from where they could operate during their travels.[29] For the second voyage, one of the main responsibilities was to confer formal investiture on the King of Calicut.[30][31] Early in the voyages, Ceylon was perceived with considerable enmity by China.[22] Its rulers were even actively hostile towards the treasure fleet when they arrived during the third voyage.[22]

On the Malabar coast, Calicut and Cochin were in an intense rivalry, so the Ming decided to intervene by granting special status to Cochin and its ruler Keyili (可亦里).[32] For the fifth voyage, Zheng He was instructed to confer a seal upon Keyili of Cochin and enfeoff a mountain in his kingdom as the Zhenguo Zhi Shan (鎮國之山, Mountain Which Protects the Country).[32] He delivered a stone tablet, inscribed with a proclamation composed by the Yongle Emperor, to Cochin.[32] As long as Cochin remained under the protection of Ming China, the Zamorin of Calicut was unable to invade Cochin and a military conflict was averted.[32] The cessation of the Ming treasure voyages consequently had a negative outcome for Cochin, because the Zamorin would eventually launch an invasion against Cochin.[32]

Coinciding with the first voyage, China was in war with Vietnam and was set on conquering it.[22] Champa was an ally of China and in state of conflict with Vietnam, thus they received the support of China.[33]

In 1408, King Ghiyath-ud-Din of Bengal sent a tribute mission to China.[34] In 1412, an envoy was sent to announce the death of King Ghiyath-ud-Din and the accession of his son Sa'if-ud-Din as the new king.[34] In 1414, King Jalal-ud-Din (r. 1414–1431) sent a giraffe as tribute to China.[34] In 1415, the Yongle Emperor sent Hou Xian to confer gifts to the king, queen, and ministers of Bengal.[34] Hou Xian was a Grand Director who had accompanied Zheng He during the second and third voyage.[34] In 1438, Bengal sent a giraffe as tribute to China.[34] In 1439, Bengal sent a tribute mission to China.[34]

Ma Huan and the Mingshi described Aden as a Muslim country whose people were overbearing and whose ruler had 7 to 8 thousand well-drilled horsemen and foot soldiers, thus the country was relatively powerful and its neighbors were fearful of it.[35] Aden's king was al-Malik an-Nasir Salah-ad-Din Ahmad (r. 1400–1424) of the Rasulid dynasty, who earlier had taken control of Yemen from the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt.[35] King Ahmad accepted the imperial edict and gifts that he received from the Chinese envoys and greeted them "with great reverence and humility" when they visited Aden during the treasure fleet's fifth voyage.[35] He may have hoped for military assistance against the threat that the Mamluk Sultanate posed at the time.[35] Even though the fleet returned in the sixth voyage, Yemen fell apart when their slave soldiers repeatedly rebelled under the reigns of King Ahmed's descendants: Abdallah, (r. 1424–1427, his son), Isma'il II (r.1427–1428, his son), and Yahya (r. 1428–1439, son of Isma'il II).[35] The Mingshi noted that Aden had sent a total of four tribute missions to China.[35]

In reference to the last expedition in connection to the Mamluk Sultanate, Ibn Taghribirdi's account, dated 21 June 1432, recorded a report that came from Mecca about two Chinese ships that had anchored at Aden after departing from India.[36] The two captains of the ships had written to Sharif Barakat ibn Hasan ibn Ajlan (Emir of Mecca) and Sa'd al-Din Ibrahim ibn al-Marra (controller of Jeddah) for permission to come to Jeddah, as stated by the report, since the cargo was not loaded off the ships in Aden due to the disorder in Yemen.[36] The account noted that the latter two wrote to the sultan about this, making him eager for the many Chinese goods, thus the sultan wrote back that the Chinese may come to Jeddah and are to be treated with honor.[36]

Several African nations sent ambassadors who presented elephants and rhinoceroses as tribute to China.[37] In 1415, Malindi presented a giraffe.[38] The final tribute mission from Malindi was in 1416, but it is not known which local products were presented to the Ming court.[39]

According to Zheng He's two inscriptions, Mogadishu presented zebras (huafulu) and lions as tribute to them during the fifth voyage.[40] The inscriptions also noted that Brava presented camels and ostriches as tribute during the voyage.[40] Brava sent a total of four tribute missions to China from 1416 to 1423.[40]

Aden had sent tribute giraffes on the fifth and sixth voyages, but the one on the fifth never arrived in China.[39] Mecca had also sent them on the seventh voyage.[39] The giraffes were not likely to be native to Aden or Mecca.[39] Bengal also sent a tribute giraffe, although it was said that it was a re-export from Malindi.[39]

Between 30 December 1418 and 27 January 1419, Ming China's treasure fleet visited Yemen under the reign of Al Malik al Nasir.[41] The Chinese envoy, presumably Admiral Zheng He, was accompanied by the Yemeni envoy Kadi Wazif al-Abdur Rahman bin-Zumeir who escorted him to the Yemeni court.[41] The Chinese brought gifts equivalent to 20,000 miscals, comprising expensive perfumes, scented wood, and Chinese potteries.[41] The Yemeni ruler sent luxury goods made from coral at the port of Ifranza, wild cattle and donkeys, domesticated lion cubs, and wild and trained leopards in exchange.[41] The Yemeni envoy accompanied the Chinese to the port of Aden with the gifts, which maintained trade under the facade of gift exchange.[41]

In 1405–1406, 1408-1410 and 1417, the treasure fleet under Zheng He visited the kingdoms of the Philippines such as Pangasinan, Manila, Mindoro and Sulu, establishing tributary relations and even stationing a "governor", Ko-ch'a-lao, to oversee them. These visits helped to elevate Sulu into a major centre of commerce.[42][43]

The passage of the treasure fleet precipitated the formation of a tributary relationship with Brunei in 1405. The Ming subsequently invested the new ruler of Brunei in 1408 while the Bruneian royals were visiting China, and freed Brunei from paying tribute to the Majapahit, which in 1407 had been successfully pressured by show of force into apologising for the mistaken killing of Ming soldiers.[44]

References[]

- ^ Finlay (2008), 330–331.

- ^ a b c d e Finlay 2008, 337.

- ^ Ray 1987b, 158.

- ^ Ray (1987b), 158.

- ^ Brook 1998, 616.

- ^ Cited in Finlay 2008, 337.

- ^ Mills 1970, 3–4.

- ^ O'Rourke & Williamson (2009), 661–663.

- ^ a b c d Ray (1987a), 81–85.

- ^ Sen (2016), 624–626.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 33.

- ^ Mills 1970, 1–2.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 343.

- ^ Fairbank 1942, 140.

- ^ Church 2004, 8.

- ^ Mills 1970, 2.

- ^ a b c Dreyer 2007, 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sen (2016), 615.

- ^ Tan (2005), 49.

- ^ a b c d Dreyer 2007, 42.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 42–43 & 61.

- ^ a b c d Dreyer 2007, 61.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer 2007, 58.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 42 & 58.

- ^ a b Dreyer 2007, 30.

- ^ a b Dreyer 2007, 57.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 57–58.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 93.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 65.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 59.

- ^ Mills 1970, 11.

- ^ a b c d e Sen (2016), 616–617.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dreyer 2007, 157.

- ^ a b c d e f Dreyer 2007, 87.

- ^ a b c Chaudhuri 1989, 112.

- ^ Dreyer 2007, 89.

- ^ Church 2004, 24.

- ^ a b c d e Dreyer 2007, 90.

- ^ a b c Dreyer 2007, 88.

- ^ a b c d e Ray 1987b, 159.

- ^ Juliet Lee Uytanlet; Michael Rynkiewich (2016). The Hybrid Tsinoys: Challenges of Hybridity and Homogeneity as Sociocultural Constructs among the Chinese in the Philippines. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 222. ISBN 1498229069.

- ^ Ho Khai Leong (2009). Connecting and Distancing: Southeast Asia and China. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 33. ISBN 9812308563.

- ^ Marie-Sybille de Vienne (2015). Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. NUS Press. pp. 40–43. ISBN 9971698188.

Bibliography[]

- Brook, Timothy (1998). "Communications and Commerce". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1398–1644, Part 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243339.

- Chaudhuri, K.N. (1989). "A Note on Ibn Taghrī Birdī's Description of Chinese Ships in Aden and Jedda". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 121 (1): 112. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00167899. JSTOR 25212419.

- Church, Sally K. (2004). "The Giraffe of Bengal: A Medieval Encounter in Ming China". The Medieval History Journal. 7 (1): 1–37. doi:10.1177/097194580400700101. S2CID 161549135.

- Dreyer, Edward L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. ISBN 9780321084439.

- Duyvendak, J.J.L. (1938). "The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century". T'oung Pao. 34 (5): 341–413. doi:10.1163/156853238X00171. JSTOR 4527170.

- Fairbank, John King (1942). "Trade and China's Relations with the West". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 1 (2): 129–149. doi:10.2307/2049617. JSTOR 2049617.

- Finlay, Robert (1992). "Portuguese and Chinese Maritime Imperialism: Camoes's Lusiads and Luo Maodeng's Voyage of the San Bao Eunuch". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 34 (2): 225–241. doi:10.1017/S0010417500017667. JSTOR 178944.

- Finlay, Robert (2008). "The Voyages of Zheng He: Ideology, State Power, and Maritime Trade in Ming China". Journal of the Historical Society. 8 (3): 327–347. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2008.00250.x.

- Mills, J.V.G. (1970). Ying-yai Sheng-lan: 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores' [1433]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01032-2.

- O'Rourke, Kevin H.; Williamson, Jeffrey G. (2009). "Did Vasco da Gama matter for European markets?". The Economic History Review. 62 (3): 655–684. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00468.x. S2CID 154740598.

- Ray, Haraprasad (1987a). "An Analysis of the Chinese Maritime Voyages into the Indian Ocean during Early Ming Dynasty and their Raison d'Etre". China Report. 23 (1): 65–87. doi:10.1177/000944558702300107. S2CID 154116680.

- Ray, Haraprasad (1987b). "The Eighth Voyage of the Dragon that Never Was: An Enquiry into the Causes of Cessation of Voyages During Early Ming Dynasty". China Report. 23 (2): 157–178. doi:10.1177/000944558702300202. S2CID 155029177.

- Sen, Tansen (2016). "The Impact of Zheng He's Expeditions on Indian Ocean Interactions". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 79 (3): 609–636. doi:10.1017/S0041977X16001038.

- Tan, Ta Sen (2005). "Did Zheng He Set Out To Colonize Southeast Asia?". Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia. Singapore: International Zheng He Society. ISBN 981-230-329-4.

- Maritime history of China

- 15th century in China

- History of foreign trade in China

- Foreign relations of the Ming dynasty

- Treasure voyages