Directional selection

In population genetics, directional selection, is a mode of negative natural selection in which an extreme phenotype is favored over other phenotypes, causing the allele frequency to shift over time in the direction of that phenotype. Under directional selection, the advantageous allele increases as a consequence of differences in survival and reproduction among different phenotypes. The increases are independent of the dominance of the allele, and even if the allele is recessive, it will eventually become fixed.[1]

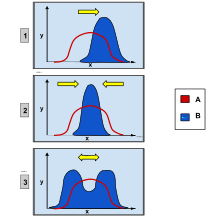

Directional selection was first described by Charles Darwin in the book On the Origin of Species as a form of natural selection.[2] Other types of natural selection include stabilizing and disruptive selection. Each type of selection contains the same principles, but is slightly different. Disruptive selection favors both extreme phenotypes, different from one extreme in directional selection. Stabilizing selection favors the middle phenotype, causing the decline in variation in a population over time.[3]

Evidence[]

Directional selection occurs most often under environmental changes and when populations migrate to new areas with different environmental pressures. Directional selection allows for fast changes in allele frequency, and plays a major role in speciation. Analysis on QTL effects has been used to examine the impact of directional selection in phenotypic diversification. This analysis showed that the genetic loci correlating to directional selection was higher than expected; meaning directional selection is a primary cause of phenotypic diversification, which leads to speciation.[4]

Detection methods[]

There are different statistical tests that can be run to test for the presence of directional selection in a population. A few of the tests include the QTL sign test, Ka/Ks ratio test and the relative rate test. The QTL sign test compares the number of antagonistic QTL to a neutral model, and allows for testing of directional selection against genetic drift.[5] The Ka/Ks ratio test compares the number of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions, and a ratio that is greater than 1 indicates directional selection.[6] The relative ratio test looks at the accumulation of advantageous against a neutral model, but needs a phylogenetic tree for comparison.[7]

Examples[]

An example of directional selection is fossil records that show that the size of the black bears in Europe decreased during interglacial periods of the ice ages, but increased during each glacial period. Another example is the beak size in a population of finches. Throughout the wet years, small seeds were more common and there was such a large supply of the small seeds that the finches rarely ate large seeds. During the dry years, none of the seeds were in great abundance, but the birds usually ate more large seeds. The change in diet of the finches affected the depth of the birds’ beaks in future generations. Their beaks range from large and tough to small and smooth.[8]

African cichlids[]

African cichlids are known to be some of the most diverse fish and evolved extremely quickly. These fish evolved within the same habitat, but have a variety of morphologies, especially pertaining to the mouth and jaw. Albertson et al. 2003 tested this by crossing two species of African cichlids with very different mouth morphologies. The cross between Labeotropheus fuelleborni (subterminal mouth for biting algae off rocks) and Metriaclima zebra (terminal mouth for suction feed) allowed for mapping of QTLs affecting feeding morphology. Using the QTL sign test definitive evidence was shown to prove that directional selection was occurring in the oral jaw apparatus. However, this was not the case for the suspensorium or skull (suggesting genetic drift or stabilizing selection).[9]

Sockeye salmon[]

Sockeye salmon are one of the many species of fish that are anadromous. Individuals migrate to the same rivers in which they were born to reproduce. These migrations happen around the same time every year, but Quinn et al. 2007 shows that sockeye salmon found in the waters of the Bristol Bay in Alaska have recently undergone directional selection on the timing of migration. In this study two populations of sockeye salmon were observed (Egegik and Ugashik). Data from 1969-2003 provided by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game were divided into five sets of seven years and plotted for average arrival to the fishery. After analyzing the data it was determined that in both populations average migration date was earlier and was undergoing directional selection. The Egegik population experienced stronger selection and shifted 4 days. Water temperature is thought to cause earlier migration date, but in this study there was no statistically significant correlation. The paper suggests that fisheries can be a factor driving this selection because fishing occurs more in the later periods of migration (especially in the Egegik district), preventing those fish from reproducing.[10]

Ecological impact[]

Directional selection can quickly lead to vast changes in allele frequencies in a population. Because the main cause for directional selection is different and changing environmental pressures, rapidly changing environments, such as climate change, can cause drastic changes within populations.

Timescale[]

Typically directional selection acts strongly for short bursts and is not sustained over long periods of time.[11] If it did, a population might hit biological constraints such that it no longer responds to selection. However, it is possible for directional selection to take a very long time to find even a local optimum on a fitness landscape.[12] A possible example of long-term directional selection is the tendency of proteins to become more hydrophobic over time,[13] and to have their hydrophobic amino acids more interspersed along the sequence.[14]

See also[]

- Adaptive evolution in the human genome

- Balancing selection

- Disruptive selection

- Frequency-dependent foraging by pollinators

- Negative selection (natural selection)

- Stabilizing selection

- Peppered moth evolution

- Fluctuating selection

References[]

- ^ Molles, MC (2010). Ecology Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill Higher Learning.

- ^ Darwin, C (1859). On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: John Murray.

- ^ Mitchell-Olds, Thomas; Willis, John H.; Goldstein, David B. (2007). "Which evolutionary processes influence natural genetic variation for phenotypic traits?". Nature Reviews Genetics. Springer Nature. 8 (11): 845–856. doi:10.1038/nrg2207. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 17943192. S2CID 14914998.

- ^ Rieseberg, Loren H.; Widmer, Alex; Arntz, A. Michele; Burke, John M. (2002-09-17). "Directional selection is the primary cause of phenotypic diversification". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (19): 12242–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9912242R. doi:10.1073/pnas.192360899. PMC 129429. PMID 12221290.

- ^ Orr, H.A. (1998). "Testing Natural Selection vs. Genetic Drift in Phenotypic Evolution Using Quantitative Trait Locus Data". Genetics. 149 (4): 2099–2104. doi:10.1093/genetics/149.4.2099. PMC 1460271. PMID 9691061.

- ^ Hurst, Laurence D (2002). "The Ka/Ks ratio: diagnosing the form of sequence evolution". Trends in Genetics. Elsevier BV. 18 (9): 486–487. doi:10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02722-1. ISSN 0168-9525. PMID 12175810.

- ^ Creevey, Christopher J.; McInerney, James O. (2002). "An algorithm for detecting directional and non-directional positive selection, neutrality and negative selection in protein coding DNA sequences". Gene. Elsevier BV. 300 (1–2): 43–51. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01039-9. ISSN 0378-1119. PMID 12468084.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2002). Biology (6th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. pp. 450–451. ISBN 978-0-8053-6624-2.

- ^ Albertson, R. C.; Streelman, J. T.; Kocher, T. D. (2003-04-18). "Directional selection has shaped the oral jaws of Lake Malawi cichlid fishes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (9): 5252–5257. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.5252A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0930235100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 154331. PMID 12704237.

- ^ Quinn, Thomas P.; Hodgson, Sayre; Flynn, Lucy; Hilborn, Ray; Rogers, Donald E. (2007). "Directional Selection by Fisheries and the Timing of Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus Nerka) Migrations". Ecological Applications. Wiley. 17 (3): 731–739. doi:10.1890/06-0771. ISSN 1051-0761. PMID 17494392.

- ^ Hoekstra, H. E.; Hoekstra, J. M.; Berrigan, D.; Vignieri, S. N.; Hoang, A.; Hill, C. E.; Beerli, P.; Kingsolver, J. G. (2001-07-24). "Strength and tempo of directional selection in the wild". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (16): 9157–9160. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.9157H. doi:10.1073/pnas.161281098. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 55389. PMID 11470913.

- ^ Kaznatcheev, Artem (May 2019). "Computational Complexity as an Ultimate Constraint on Evolution". Genetics. 212 (1): 245–265. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302000. PMC 6499524. PMID 30833289.

- ^ Wilson, Benjamin A.; Foy, Scott G.; Neme, Rafik; Masel, Joanna (24 April 2017). "Young genes are highly disordered as predicted by the preadaptation hypothesis of de novo gene birth" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (6): 0146–146. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0146. hdl:10150/627822. PMC 5476217. PMID 28642936.

- ^ Foy, Scott G.; Wilson, Benjamin A.; Bertram, Jason; Cordes, Matthew H. J.; Masel, Joanna (April 2019). "A Shift in Aggregation Avoidance Strategy Marks a Long-Term Direction to Protein Evolution". Genetics. 211 (4): 1345–1355. doi:10.1534/genetics.118.301719. PMC 6456324. PMID 30692195.

Further reading[]

- Sabeti PC; et al. (2006). "Positive Natural Selection in the Human Lineage". Science. 312 (5780): 1614–1620. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1614S. doi:10.1126/science.1124309. PMID 16778047. S2CID 10809290.

- Pickrell JK, Coop G, Novembre J, et al. (May 2009). "Signals of recent positive selection in a worldwide sample of human populations". Genome Research. 19 (5): 826–837. doi:10.1101/gr.087577.108. PMC 2675971. PMID 19307593.

- Types of Selection

- Natural Selection

- Modern Theories of Evolution

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Directional selection. |

- Selection