District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

|

The District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution that would have given the District of Columbia full representation in the United States Congress, full representation in the Electoral College system, and full participation in the process by which the Constitution is amended. It would have also repealed the Twenty-third Amendment, which granted the District of Columbia the same number of electoral votes as that of the least populous state, but gave it no role in contingent elections.

The amendment was proposed by the U.S. Congress on August 22, 1978, and the legislatures of the 50 states were given seven years to consider it. Ratification by 38 states was necessary for the amendment to become part of the Constitution; only 16 states had ratified it when the seven-year time limit expired on August 22, 1985. This proposed constitutional amendment is the most recent one to have been sent to the states for their consideration.[1]

Text[]

Section 1. For purposes of representation in the Congress, election of the President and Vice President, and article V of this Constitution, the District constituting the seat of government of the United States shall be treated as though it were a State.

Section 2. The exercise of the rights and powers conferred under this article shall be by the people of the District constituting the seat of government, and as shall be provided by the Congress.

Section 3. The twenty-third article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

Section 4. This article shall be inoperative, unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States within seven years from the date of its submission.[2]

Legislative history[]

Representative Don Edwards of California proposed House Joint Resolution 554 in the 95th Congress. The United States House of Representatives passed it on March 2, 1978, by a 289–127 vote, with 18 not voting.[3] The United States Senate passed it on August 22, 1978, by a 67–32 vote, with 1 not voting.[4] With that, the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment was submitted to the state legislatures for ratification. The Congress, via Section 4, included in the text of the proposed amendment the requirement that ratification by three-fourths (38) of the states be completed within seven years following its passage by the Congress (i.e., August 22, 1985) in order for the proposed amendment to become part of the Constitution.[5] By placing the ratification deadline in the text of the proposed amendment the deadline could not be extended without a separate amendment to the Constitution, different from what had been done regarding the Equal Rights Amendment which was on restricted by statute and not the amendment itself.[6]

Ratification history[]

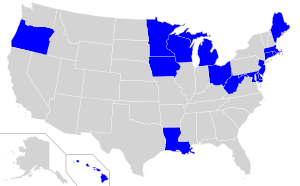

Ratification status of the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment Ratified amendment |

Ratification by the legislatures of at least 38 of the 50 states by August 22, 1985, was necessary for the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment to become part of the Constitution. During the seven-year period specified by Congress it was ratified by only 16 states and so failed to be adopted.[7] The amendment was ratified by the following states:

- New Jersey on September 11, 1978

- Michigan on December 13, 1978

- Ohio on December 21, 1978

- Minnesota on March 19, 1979

- Massachusetts on March 19, 1979

- Connecticut on April 11, 1979

- Wisconsin on November 1, 1979

- Maryland on March 19, 1980

- Hawaii on April 17, 1980

- Oregon on July 6, 1981

- Maine on February 16, 1983

- West Virginia on February 23, 1983

- Rhode Island on May 13, 1983

- Iowa on January 19, 1984

- Louisiana on June 24, 1984

- Delaware on June 28, 1984

Effects if it had been adopted[]

Had it been adopted, this proposed amendment would have given the District of Columbia most of the same rights as a state, but it would not have made the district into a state, or affected Congress's authority over it. The District of Columbia would have been given full representation in both houses of Congress, so that it would have two senators and a variable number of representatives based on population.

The proposed amendment would also have repealed the Twenty-third Amendment. The Twenty-third Amendment does not allow the district to have more electoral votes "than the least populous State", nor does it grant the District of Columbia any role in contingent elections of the president by the House of Representatives (or of the vice president by the Senate). In contrast, this proposed amendment would have provided the district full participation in presidential elections.

Finally, the proposed amendment would have allowed the Council of the District of Columbia, the Congress, or the people of the district (depending on how the amendment would have been interpreted) to decide whether to ratify any proposed amendment to the Constitution, or to apply to the Congress for a convention to propose amendments to the United States Constitution, just as a state's legislature can under the Constitutional amendment process laid out in Article V of the Constitution.[8]

See also[]

- District of Columbia voting rights

- List of amendments to the United States Constitution, amendments sent to the states, both ratified and unratified

- List of proposed amendments to the United States Constitution, amendments proposed in Congress but never sent to the states for ratification

References[]

- ^ DeSilver, Drew (April 12, 2018) [Update, originally published September 17, 2014]. "Proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution seldom go anywhere". Pew Research Center. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ^ "Constitutional Amendments Not Ratified". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ 124 Congressional Record 5272–5273

- ^ 124 Congressional Record 27260

- ^ In Dillon v. Gloss, 256 U.S. 368 (1921), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Congress's authority to impose time limits on ratification.

- ^ Neale, Thomas (May 9, 2013). "The Proposed Equal Rights Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. pp. 24–26. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "The 1978 D.C. Voting Representation Constitutional Amendment". DC Vote. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "Nevada State Legislature - Background Paper 79-3" (PDF).

- Unratified amendments to the United States Constitution

- History of the District of Columbia

- Home rule and voting rights of the District of Columbia

- 1978 documents

- 95th United States Congress

- Legal history of the District of Columbia