Dracula (1979 film)

| Dracula | |

|---|---|

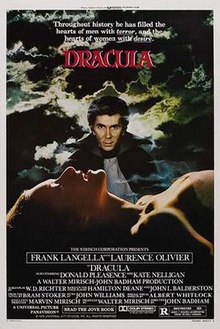

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Badham |

| Screenplay by | W. D. Richter |

| Based on |

|

| Produced by | Marvin Mirisch Walter Mirisch |

| Starring | Frank Langella Laurence Olivier Donald Pleasence Kate Nelligan |

| Cinematography | Gilbert Taylor |

| Edited by | John Bloom |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | The Mirisch Company |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12.2 million |

| Box office | $31.2 million |

Dracula is a 1979 British-American horror film directed by John Badham. The film starred Frank Langella in the title role as well as Laurence Olivier, Donald Pleasence and Kate Nelligan.

The film was based on Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula and its 1924 stage adaptation, though much of Stoker's original plot was revised to make the film—which was advertised with the tagline "A Love Story"—more romantic. The film won the 1979 Saturn Award for Best Horror Film.

Plot[]

In Whitby, England in 1913, Count Dracula arrives from Transylvania via the ship Demeter one stormy night. Mina van Helsing, who is visiting her friend Lucy Seward, discovers Dracula's body after his ship has run aground and rescues him. The Count visits Mina and her friends at the household of Lucy's father, Dr. Jack Seward, whose clifftop mansion also serves as the local asylum. At dinner, he proves to be a charming guest and leaves a strong impression on the hosts, especially Lucy. Less charmed by this handsome Romanian count is Jonathan Harker, Lucy's fiancé.

Later that night, while Lucy and Jonathan are having a secret rendezvous, Dracula reveals his true nature as he descends upon Mina to drink her blood. The following morning, Lucy finds Mina awake in bed, struggling for breath. Powerless, she watches her friend die, only to find wounds on her throat. Lucy blames herself for Mina's death, as she had left her alone.

At a loss for the cause of death, Dr. Seward calls for Mina's father, Professor Abraham van Helsing, who suspects what might have killed his daughter: a vampire. He begins to worry about what fate his seemingly dead daughter may now have. Seward and van Helsing investigate their suspicions and discover a roughly clawed opening within Mina's coffin which leads to the local mines. It is there that they encounter the ghastly form of an undead Mina and it is up to a distraught van Helsing to destroy what remains of his daughter.

Lucy has in the meantime been summoned to Carfax Abbey, Dracula's new home. She reveals herself to be in love with this foreign prince and openly offers herself to him as his bride. After a surreal "wedding night" sequence, Lucy, like Mina before her, is now infected by Dracula's blood. The two doctors manage to give Lucy a blood transfusion to slow her descent into vampirism but she remains under Dracula's spell.

Now aided by Jonathan, the elderly doctors realize that the only way to save Lucy is by destroying Dracula. They manage to locate his coffin within the grounds of Carfax Abbey but the vampire is waiting for them. Despite it being daylight, Dracula is still a very powerful adversary. Dracula escapes their attempts to kill him, bursts into the asylum to free the captive Lucy and also scolds his slave, Milo Renfield, for warning the others about him. Renfield apologises and pleads for his life, but Dracula kills him by breaking his neck. Dracula makes preparations for him and Lucy to return to Transylvania.

Harker and van Helsing make it on board a ship carrying Dracula and Lucy cargo bound for Romania. Below decks, Harker and van Helsing find Dracula and Lucy sleeping together in the coffin. Van Helsing attempts to stake Dracula, but Lucy protests, waking Dracula. In the struggle, van Helsing is fatally wounded by Dracula as he is impaled with the stake intended for the vampire. Dracula now draws his attention on Harker. Van Helsing uses his remaining strength to throw a hook attached to a rope, tied to the ship's rigging, into Dracula's back. Harker seizes his chance and hoists the count up through the cargo hold to the top of the ship's rigging, where he dies a painful death when the rays of the sun burn his body.

Van Helsing dies from his wounds. Lucy is now apparently herself again, and Harker comforts her. Lucy smiles as she notices Dracula's cape blow away into the horizon, hinting Dracula may have survived.

Cast[]

- Frank Langella as Count Dracula

- Laurence Olivier as Professor Abraham Van Helsing

- Donald Pleasence as Dr. Jack Seward

- Kate Nelligan as Lucy Seward

- Jan Francis as Mina Van Helsing

- Trevor Eve as Jonathan Harker

- Tony Haygarth as Milo Renfield

- Sylvester McCoy as Walter Myrtle

- Janine Duvitski as Annie

- Teddy Turner as Swales

Production[]

Like Universal's earlier 1931 version starring Bela Lugosi, the screenplay for this adaptation of Bram Stoker's novel Dracula is based on the stage adaptation by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston, which ran on Broadway and also starred Langella in a Tony Award-nominated performance. Set in the Edwardian period, and strikingly designed by Edward Gorey, the play ran for over 900 performances between October 1977 and January 1980. It is also known for switching names of characters of Mina Harker and Lucy Westenra. When Badham was asked, why he switched their names in his film, he said that he couldn't quite remember and that maybe he and Richter felt like Mina was a dopey name and that Lucy was kind of a nice name, so they rearranged it.[1]

The film was shot on location in England: at Shepperton Studios and Black Park, Buckinghamshire. Cornwall doubled for the majority of the exterior Whitby scenes; Tintagel (for Seward's Asylum), and St Michael's Mount (for Carfax Abbey). The Castle Dracula was a glass matte painted by Albert Whitlock.[2]

Gilbert Taylor was the cinematographer, while the original music score was contributed by John Williams.

According to Frank Langella, Count Dracula was "a dominant, aggressive force. He must have Miss Lucy or he dies. He wants what he wants and he doesn't analyze it. Dracula as a character is very erotic. ... A woman can be totally passive with Dracula: 'he made me drink, I couldn't help it.' ... Dracula seems to represent a kind of doorway to sexual abandonment not possible with a mere mortal. Besides, he's offering immortality. Actually, I can't think of a woman who wouldn't like to be taken if it's with love. If you take a woman by force and at the same time gently, you can't fail."[3]

Langella wanted to explore sides of the character which weren't shown before: "I decided he was a highly vulnerable and erotic man, not cool and detached and with no sense of humour or humanity. I didn't want him to appear stilted, stentorian or authoritarian as he's often presented. I wanted to show a man who, while evil, was lonely and could fall in love".[4]

Langella holds this view many years after the release of the movie. In his 2017 interview during SITGES film festival he said that he "saw a gentleman in [Dracula], while the bad guys were the ones who wanted to destroy him, and we see that today in many instances: ignorance leads to the desire to destroy different people, there is the suffering of homosexuals, or women." Langella remembers that the beginning of shooting was very disorganized. The cinematographer was changed and they had continual changes of plans. However, the actor mentioned that the process "turned out well" in the end.[5]

However, the most vivid memories were Langella's efforts to create a different Dracula. "I did not want to look like Bela Lugosi, or Christopher Lee", remembers Langella. He thus read the novel and found the character to be "gothic, elegant, lonely, without anyone who understood his problem, which consisted of the need for blood to survive." Langella also understood that the attraction that the character produced among women was key to realize his enormous "power of seduction", which Langella did not hesitate to use.[6]

Reception[]

Box office[]

In 1979, at least three Dracula films were released around the world: West German director Werner Herzog's retelling as Nosferatu the Vampyre, this film, and the comedy Love at First Bite. The success of the jokey Love at First Bite, starring George Hamilton, may have had something to do with the muted response this version would subsequently experience. The film opened at number one at the US box office with an opening weekend gross of $3,141,281 nationally from 455 theaters[7][8] but performed modestly at the box office, grossing $20,158,970 domestically, and was seen as something of a disappointment by the studio.

Critical Response[]

Some critics reacted toward the film with praise, such as Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, who gave it 3½ stars out of 4 and wrote: "What an elegantly seen Dracula this is, all shadows and blood and vapors and Frank Langella stalking through with the grace of a cat. The film is a triumph of performance, art direction and mood over materials that can lend themselves so easily to self-satire...This Dracula restores the character to the purity of its first film appearances..."[9] Others reacted with less praise, such as Janet Maslin of The New York Times, who wrote: "In making this latest trip to the screen in living color, Dracula has lost some blood. The movie version ... is by no means lacking in stylishness; if anything, it's got style to spare. But so many of its sequences are at fever pitch, and the mood varies so drastically from episode to episode, that the pace becomes pointless, even taxing, after a while."[10] Film historian Leonard Maltin seemed to agree with Maslin, giving the picture 1.5 out of a possible 4 stars, and describing it as "Murky...with Langella's acclaimed Broadway interpretation sabotaged by trendy horror gimmicks and ill-conceived changes to Bram Stoker's novel."[11]

Accolades[]

| Year | Award / Film Festival | Category | Recipient(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 9th Paris International Festival of Fantastic and Science-Fiction Film | Golden Licorn (Best Film) | Dracula | Won |

| 1979 | Saturn Awards | Best Horror Film | Dracula | Won |

| Best Actor | Frank Langella | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Donald Pleasence | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | John Badham | Nominated | ||

| Best Make-up | Peter Robb-King | Nominated |

Home video[]

The movie made it onto Variety's All-Time Horror Rentals in 1993, but it eventually seemed to fall into relative cinematic obscurity for several years, partly due to it having a very limited video release outside of the USA.[citation needed]

Video recoloring[]

The 1979 theatrical version looks noticeably different from later prints. When the film was reissued for a widescreen laserdisc release in 1991, the director chose to alter the color timing, desaturating the look of the film.

John Badham had intended to shoot the film in black and white (to mirror the monochrome 1931 film and the stark feel of the Gorey stage production), but Universal executives objected. Cinematographer Gilbert Taylor was prompted to shoot the movie in warm, "golden" colours, to show off the distinctive production design. The original version has not been widely screened since the 1980s. Other than an occasional broadcast, such as on TCM in a pan and scan format, the movie has effectively been out of print.

In 2018 a 2.35:1 aspect ratio fan edit restored the theatrical color timing based on the original laserdisc and VHS releases, as well as set photography and reference materials prompting an official release the following year.

A July 2019 Shout! Factory announcement revealed that the movie had been licensed to release the original 1979 theatrical color version of Dracula on blu-ray; it was released in November of 2019.[citation needed] This is the first time the original 1979 Dracula has been made commercially available since first being released on VHS and laserdisc in 1982.[citation needed] It also includes the previously available desaturated version on another disc.

In November 2020, Black Hill Pictures and KOCH Media released a newly restored "cinema edition" featuring the 1979 color version of Dracula on Blu-ray (Region B/2). This is the second time the original 1979 version has been made commercially available making use of higher quality source materials after the release of Shout! Factory's more aged color print.[citation needed]

See also[]

- Vampire films

References[]

- ^ Tom Weaver (2004): "Science Fiction and Fantasy Film Flashbacks", p.36

- ^ Mooser, Stephen (1983). Lights! Camera! Scream!. Julian Messner. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-671-43017-7.

- ^ "Dracula 1979: Celebrating Frank Langella's Rock Star Count". Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Film Review: 25. October 1979. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Sitges 2017: Press conference – Frank Langella". YouTube.

- ^ "Frank Langella: Drácula no era un chupasangre, sólo era un hombre con miedo". La Vanguardia. 13 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "50 Top-Grossing Films". Variety. 25 July 1979. p. 9.

- ^ "New No. 1 Fang". Variety. 18 July 1979. p. 5.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (20 July 1979), "Dracula", Review, rogerebert.com

- ^ Maslin, Janet (13 July 1979), "Screen: Langella's Seductive 'Dracula' Adapted From Stage", The New York Times

- ^ Maltin's TV, Movie, & Video Guide

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dracula (1979 film) |

- Dracula at IMDb

- Dracula at the Internet Broadway Database

- Dracula at AllMovie

- Dracula at Box Office Mojo

- Dracula at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1979 films

- English-language films

- Dracula films

- 1979 horror films

- American supernatural horror films

- American films

- British supernatural horror films

- British films

- Films scored by John Williams

- Films directed by John Badham

- Films produced by Walter Mirisch

- British films based on plays

- American films based on plays

- Films set in 1913

- Films set in England

- Romantic horror films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films with screenplays by W. D. Richter

- Films based on adaptations

- Films based on multiple works