Dracunculiasis

| Dracunculiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Guinea-worm disease |

| |

| Using a matchstick to wind up and remove a guinea worm from the leg of a human | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Painful blister on lower leg[1] |

| Usual onset | Average time of one year after exposure[1] |

| Causes | Guinea worms spread by water fleas[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptom[2] |

| Prevention | Preventing those infected from putting the wound in drinking water, treating contaminated water[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[1] |

| Frequency | 54 reported cases (2019)[3][4] |

| Deaths | Rare |

Dracunculiasis, also called Guinea-worm disease, is a parasitic infection by the Guinea worm.[1] A person becomes infected from drinking water that contains water fleas infected with guinea worm larvae.[1] Initially there are no symptoms.[5] About one year later, the female worm forms a painful blister in the skin, usually on a lower limb.[1] Other symptoms at this time may include vomiting and dizziness.[5] The worm then emerges from the skin over the course of a few weeks.[6] During this time, it may be difficult to walk or work.[5] It is very uncommon for the disease to cause death.[1]

In humans, the only known cause is Dracunculus medinensis.[5] The worm is about one to two millimeters wide, and an adult female is 60 to 100 centimeters long (males are much shorter at 12–29 mm or 0.47–1.14 in).[1][5] Outside humans, the young form can survive up to three weeks,[7] during which they must be eaten by water fleas to continue to develop.[1] The larva inside water fleas may survive up to four months.[7] Thus, for the disease to remain in an area, it must occur each year in humans.[8] A diagnosis of the disease can usually be made based on the signs and symptoms.[2]

Prevention is by early diagnosis of the disease followed by keeping the infected person from putting the wound in drinking water, thus decreasing the spread of the parasite.[1] Other efforts include improving access to clean water and otherwise filtering water if it is not clean.[1] Filtering through a cloth is often enough to remove the water fleas.[6] Contaminated drinking water may be treated with a chemical called temefos to kill the water flea larva.[1] There is no medication or vaccine against the disease.[1] The worm may be slowly removed over a few weeks by rolling it over a stick.[5] The ulcers formed by the emerging worm may get infected by bacteria.[5] Pain may continue for months after the worm has been removed.[5]

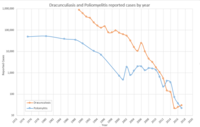

In 2019, 54 cases were reported across 4 countries.[4][3] This is down from an estimated 3.5 million cases in 1986.[5] In 2016 the disease occurred in three countries, all in Africa, down from 20 countries in the 1980s.[1][9] It will likely be the first parasitic disease to be globally eradicated.[10] Guinea worm disease has been known since ancient times.[5] The method of removing the worm is described in the Egyptian medical Ebers Papyrus, dating from 1550 BC.[11] The name dracunculiasis is derived from the Latin "affliction with little dragons",[12] while the name "guinea worm" appeared after Europeans saw the disease on the Guinea coast of West Africa in the 17th century.[11] Other Dracunculus species are known to infect various mammals, but do not appear to infect humans.[13][14] Dracunculiasis is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[15] Because dogs may also become infected,[16] the eradication program is monitoring and treating dogs as well.[17]

Signs and symptoms[]

The first signs of dracunculiasis usually occur around a year after infection, as the full-grown female worm prepares to leave the infected person's body.[18] As the worm migrates to its final site – typically the lower leg – some people have allergic reactions to the worm, including hives, fever, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.[19] When the worm reaches its destination, it forms a fluid-filled blister under the skin.[20] Over several days, the blister grows larger and begins to cause severe burning pain.[18] When an infected person submerges the blister in water to soothe the pain, the blister ruptures and the female worm begins to emerge.[20] The wound remains intensely painful as the female worm slowly emerges from the wound over the course of several weeks to months.[21] An infected person can often harbor multiple worms – up to 40 at a time – which will emerge from separate blisters at the same time.[19]

Open wounds that the worms are emerging from often become infected with bacteria, resulting in redness and swelling, the formation of abscesses, or in severe cases gangrene, sepsis or lockjaw.[18][22] When the secondary infection is near a joint (typically the ankle), the damage to the joint can result in stiffness, arthritis, or contractures.[22][23]

Cause[]

Dracunculiasis is caused by infection with the roundworm Dracunculus medinensis.[24] D. medinensis larvae reside within small aquatic crustaceans called copepods. When humans drink the water, they can unintentionally ingest infected copepods. During digestion the copepods die, releasing the D. medinensis larvae. The larvae exit the digestive tract by penetrating the stomach and intestine, taking refuge in the abdomen or retroperitoneal space.[25] Over the next two to three months the larvae develop into adult male and female worms. The male remains small at 4 cm (1.6 in) long and 0.4 mm (0.016 in) wide; the female is comparatively large, often over 100 cm (39 in) long and 1.5 mm (0.059 in) wide.[20] Once the worms reach their adult size they mate, and the male dies.[19] Over the ensuing months, the female migrates to connective tissue or along bones, and continues to develop.[19]

About a year after initial infection, the female migrates to the skin, forms an ulcer, and emerges. When the wound touches freshwater, the female spews a milky-white substance containing hundreds of thousands of larvae into the water.[21][19] Over the next several days as the female emerges from the wound, she can continue to discharge larvae into surrounding water.[21] The larvae are eaten by copepods, and after two to three weeks of development, they are infectious to humans again.[26]

Diagnosis[]

Dracunculiasis is diagnosed by visual examination – the thin white worm emerging from the blister is unique to guinea worm disease.[27] Dead worms sometimes calcify and can be seen in the subcutaneous tissue by x-ray.[22][27]

Treatment[]

There is no vaccine or medicine to treat or prevent Guinea worm disease.[28] Instead, treatment focuses on slowly and carefully removing the worm from the wound over days to weeks.[29] Once the blister bursts and the worm begins to emerge, the wound is soaked in a bucket of water, allowing the worm to empty itself of larvae away from a source of drinking water.[29] As the first part of the worm emerges, it is typically wrapped around a piece of gauze or a stick to maintain steady tension on the worm, encouraging its exit.[29] Each day, several centimeters of the worm emerge from the blister, and the stick is wound to maintain tension.[19] This is repeated daily until the full worm emerges, typically within a month.[19] If too much pressure is applied at any point, the worm can break and die, leading to severe swelling and pain at the site of the ulcer.[19]

Treatment for dracunculiasis also tends to include regular wound care to avoid infection of the open ulcer while the worm is leaving. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends cleaning the wound before the worm emerges. Once the worm begins to exit the body, the CDC recommends daily wound care: cleaning the wound, applying antibiotic ointment, and replacing the bandage with fresh gauze.[29] Painkillers like aspirin or ibuprofen can help ease the pain of the worm's exit.[19][29]

Outcomes[]

Dracunculiasis is a debilitating disease, causing substantial disability in around half of those infected.[22] People with worms emerging can be disabled for the three to ten weeks it takes the worms to fully emerge.[22] When worms emerge near joints, the inflammation around a dead worm, or infection of the open wound can result in permanent stiffness, pain, or destruction of the joint.[22] Some people with dracunculiasis have continuing pain for the 12 to 18 months after the worm has emerged.[19] Around 1% of dracunculiasis cases result in death from secondary infections of the wound.[22]

When dracunculiasis was widespread, it would often affect entire villages at once.[23] Outbreaks occurring during planting and harvesting seasons could severely impair a community's agricultural operations – earning dracunculiasis the moniker "empty granary disease" in some places.[23]

Dracunculiasis prevents many people from working or attending school for as long as three months. In heavily burdened agricultural villages fewer people are able to tend their fields or livestock, resulting in food shortages and lower earnings.[10][30] A study in southeastern Nigeria, for example, found that rice farmers in a small area lost US$20 million in just one year due to outbreaks of Guinea worm disease.[10]

Infection does not create immunity, so people can repeatedly experience Dracunculiasis throughout their lives.[31]

Prevention[]

There is no vaccine to prevent dracunculiasis. Once infected with D. medinensis there is no way to prevent the disease from running its full course. Consequently, nearly all effort to reduce the burden of dracunculiasis focuses on preventing the transmission of D. medinensis from person to person. This is primarily accomplished by filtering drinking water to physically remove copepods. Nylon filters, finely woven cloth, or specialized filter straws can all effectively remove copepods from the water.[19][32] Additionally, sources of drinking water can be treated with the larvicide temephos, which kills copepods.[33] Where possible, open sources of drinking water are replaced by deep wells that can serve as new sources of clean water.[33]

Sources of drinking water can be protected through public education campaigns, informing people in affected areas how dracunculiasis spreads, and encouraging those with the disease to avoid soaking their wound in bodies of water that are used for drinking.[19]

Since humans are the principal host for Guinea worm, and there is no evidence that D. medinensis has ever been reintroduced to humans in any formerly endemic country as the result of non-human infections, the disease can be controlled by identifying all cases and modifying human behavior to prevent it from recurring.[10][34]

Prevention methods include:

- Filter all drinking water, using a fine-mesh cloth filter, to remove the guinea worm-containing crustaceans. Regular cotton cloth folded over a few times is an effective filter. A portable plastic drinking straw containing a nylon filter has proven popular.[35]

- Filter the water through ceramic or sand filters.

- Boil the water.

- Community-level case detection and containment is key. For this, staff must go door to door looking for cases, and the population must be willing to help and not hide their cases.

- Immerse emerging worms in buckets of water to reduce the number of larvae in those worms, and then discard that water on dry ground.

- Discourage all members of the community from setting foot in the drinking water source.

- Guard local water sources to prevent people with emerging worms from entering.

Epidemiology[]

In 2020 there were just 27 cases of dracunculiasis worldwide: 12 in Chad, 11 in Ethiopia, and 1 each in Angola, Cameroon, Mali, and South Sudan.[37] This is down from 54 cases reported in 2019, and dramatically less than the estimated 3.5 million annual cases in 20 countries in 1986 – the year the World Health Assembly called for dracunculiasis' eradication.[38] Dracunculiasis is a disease of extreme poverty, occurring in places where there is poor access to clean drinking water.[39]

In December 1996, Cuba was certified free of the disease. By 1997 and 1998 further countries in the Americas were similarly certified, including Barbados, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Jamaica and Mexico.[40] Worldwide, in 2017 the number of cases had been reduced by more than 99.999% to 30 occurrences in four remaining countries in Africa: South Sudan, Chad, Mali and Ethiopia.[41]

Endemic countries must document the absence of indigenous cases of Guinea worm disease for at least three consecutive years to be certified as Guinea worm-free.[42] The results of this certification scheme have been remarkable: by 2017, 15 formerly endemic countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Cote d'lvoire, Ghana, India, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal, Togo, Uganda and Yemen—were certified to have eradicated the disease.[43]

In drier areas just south of the Sahara desert, cases of the disease often emerge during the rainy season, which for many agricultural communities is also the planting or harvesting season. Elsewhere, the emerging worms are more prevalent during the dry season, when ponds and lakes are smaller and copepods are thus more concentrated in them. Guinea worm disease outbreaks can cause serious disruption to local food supplies and school attendance.[44]

Current situation[]

In 2017, 30 human cases were reported — 15 in Chad and 15 in Ethiopia; 13 of which were fully contained. For the first time ever, South Sudan reported no human infections for a whole calendar year: the last reported case was on 20 November 2016. No human cases were reported in Mali for the second year in a row.[45] In addition to their human cases, Chad reported 817 infected dogs and 13 infected domestic cats, and Ethiopia reported 11 infected dogs and 4 infected baboons. Despite no human infections, Mali reported 9 infected dogs and 1 infected cat.[45]

By May 2018, only three human cases had been reported worldwide. All three were in Chad according to The Carter Center.[46] According to WHO, as of 31 October 2018, that number had increased to 21 human cases in 18 villages (8 villages in Chad, 9 in South Sudan and one in Angola). Over 1000 infected dogs were reported from Chad (1001), Ethiopia (11) and Mali (16) compared with 748 infected dogs for the same period in 2017. The increase in number does not necessarily mean that there are more infections - detection in animals only recently started and was likely under-reported.[citation needed]

There were 54 cases in 2019.[3][4] Provisional figures for 2020 indicate 27 cases from January to November, primarily in Chad and Ethiopia.[4]

There was evidence of re-emergence in Ethiopia (2008) and in Chad (2010) where transmission re-occurred after the country reported zero cases for almost 10 years.[28] These two countries accounted for 24 of 27 cases worldwide reported from January 1, 2020, to November 30, 2020.[4]

Endemic countries[]

At the end of 2015, South Sudan, Mali, Ethiopia and Chad still had endemic transmissions. For many years the major focus was South Sudan (independent after 2011, formerly the southern region of Sudan), which reported 76% of all cases in 2013.[41] In 2017 only Chad and Ethiopia had cases.[47]

| Date | South Sudan | Mali | Ethiopia | Chad | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||

| 2011 | 1,028[48] | 12[48] | 8[48] | 10[48] | 1058 |

| 2012 | 521[48] | 7[48] | 4[48] | 10[48] | 542 |

| 2013 | 113[48] | 11[48] | 7[48] | 14[48] | 148 (including 3 exported to Sudan) |

| 2014 | 70[48] | 40[48] | 3[48] | 13[48] | 126 |

| 2015 | 5[48] | 5[48] | 3[48] | 9[48] | 22 |

| 2016 | 6[48] | 0[48] | 3[48] | 16[48] | 25 |

| 2017 | 0[45] | 0[45] | 15[45] | 15[45] | 30 |

| 2018 | 10[49] | 0[49] | 0[49] | 17[49] | 28 (including one isolated case in Angola) |

| 2019 | 4[49] | 0[49] | 0[49] | 47[49] | 54[4][3] (including one isolated case each in Angola and Cameroon)[51] |

| 2020 | 1[52] | 1[52] | 11[52] | 12[52] | 27[52] (including one isolated case each in Angola and Cameroon; 2020 figures provisional until certified) |

History[]

Dracunculiasis has been a recognized disease for thousands of years:

- Guinea worm has been found in calcified Egyptian mummies.[10]

- An Old Testament description of "fiery serpents" may have been referring to Guinea worm: "And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died." (Numbers 21:4–9).[11]

- In the 2nd century BC, the Greek writer Agatharchides described this affliction as being endemic amongst certain nomads in what is now Sudan and along the Red Sea.[53][11]

- In the 18th century, Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus identified D. medinensis in merchants who traded along the Gulf of Guinea (West African Coast).

- Guinea worms were described by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr as "[burrowing] into the naked feet of West-Indian slaves..."[54]

This is nearly the same treatment that is noted in the famous ancient Egyptian medical text, the Ebers papyrus from c. 1550 BC.[11]

It has been suggested that the Rod of Asclepius (a symbol that represents medical practice) represents a Guinea worm wrapped around a stick for extraction.[55] According to this thinking, physicians might have advertised this common service by posting a sign depicting a worm on a rod. However plausible, there is no concrete evidence in support of this notion.

The Russian scientist Alexei Pavlovich Fedchenko (1844–1873) during the 1860s while living in Samarkand was provided with a number of specimens of the worm by a local doctor which he kept in water. While examining the worms Fedchenko noted the presence of water fleas with embryos of the guinea worm within them.[56]

In modern times, the first to describe dracunculiasis and its pathogenesis was the Bulgarian physician Hristo Stambolski, during his exile in Yemen (1877–1878).[57] He correctly inferred that the cause was infected water which people were drinking.

Eradication program[]

The campaign to eradicate dracunculiasis began at the urging of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1980.[58] Following smallpox eradication (last case in 1977; eradication certified in 1981), dracunculiasis was considered an achievable eradication target since it was relatively uncommon and preventable with only behavioral changes.[59] In 1986, the 39th World Health Assembly issued a statement endorsing dracunculiasis eradication and calling on member states to craft eradication plans.[59]

Over the years, the eradication program has faced several challenges:

- Inadequate security in some endemic countries

- Lack of political will from the leaders of some of the countries in which the disease is endemic

- The need for change in behaviour in the absence of a magic bullet treatment like a vaccine or medication

- Inadequate funding at certain times[12]

- The newly recognised transmission of guinea worm through non-human hosts (both domestic and wild animals)

Etymology[]

Dracunculiasis once plagued a wide band of tropical countries in Africa and Asia. Its Latin name, Dracunculus medinensis ("little dragon from Medina"), derives from its one-time high incidence in the city of Medina (in modern Saudi Arabia), and its common name, Guinea worm, is due to a similar past high incidence along the Guinea coast of West Africa.[11] It is no longer endemic in either location.[60]

Other animals[]

Until recently humans and water fleas (Cyclops) were regarded as the only animals this parasite infects. It has been shown that baboons, cats, dogs, frogs and catfish (Synodontis) can also be infected naturally. Ferrets have been infected experimentally.[61]

In March 2016, the World Health Organization convened a scientific conference to study the emergence of cases of infections of dogs. The worms are genetically indistinguishable from the Dracunculus medinensis that infects humans. The first case was reported in Chad in 2012; in 2016, there were more than 1,000 cases of dogs with emerging worms in Chad, 14 in Ethiopia, and 11 in Mali.[62] It is unclear if dog and human infections are related. It is possible that dogs may spread the disease to people, that a third organism may be able to spread it to both dogs and people, or that this may be a different type of Dracunculus. The current (as of 2014) epidemiological pattern of human infections in Chad appears different, with no sign of clustering of cases around a particular village or water source, and a lower average number of worms per individual.[63]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease) Fact sheet N°359 (Revised)". World Health Organization. March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cook, Gordon (2009). Manson's tropical diseases (22nd ed.). Edinburgh: Saunders. p. 1506. ISBN 978-1416044703. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". World Health Organization. 16 March 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "View Latest Worldwide Guinea Worm Case Totals". www.cartercenter.org. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Greenaway, C (February 17, 2004). "Dracunculiasis (guinea worm disease)". CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (4): 495–500. PMC 332717. PMID 14970098.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cairncross, S; Tayeh, A; Korkor, AS (June 2012). "Why is dracunculiasis eradication taking so long?". Trends in Parasitology. 28 (6): 225–230. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.03.003. PMID 22520367.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Junghanss, Jeremy Farrar, Peter J. Hotez, Thomas (2013). Manson's tropical diseases (23rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier/Saunders. p. e62. ISBN 978-0702053061. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ "Parasites – Dracunculiasis (also known as Guinea Worm Disease) Eradication Program". CDC. November 22, 2013. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ "Guinea Worm Cases Left in the World". Carter Center. Jan 12, 2015. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Guinea Worm Eradication Program". Carter Center. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Tropical Medicine Central Resource. "Dracunculiasis". Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Archived from the original on 2008-12-29. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barry M (June 2007). "The tail end of guinea worm – global eradication without a drug or a vaccine". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (25): 2561–2564. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078089. PMID 17582064.

- ^ Junghanss, Jeremy Farrar, Peter J. Hotez, Thomas (2013). Manson's tropical diseases (23rd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 763. ISBN 978-0702053061. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ^ "North American Guinea Worm". Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. June 6, 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and, Prevention (25 October 2013). "Progress toward global eradication of dracunculiasis – January 2012 – June 2013". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 62 (42): 829–833. PMC 4585614. PMID 24153313.

- ^ WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis, CDC (March 25, 2016). "Guinea Worm Wrap-Up #239" (PDF). Carter Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Guinea Worm - Disease". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 August 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Spector & Gibson 2016, p. 110.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Despommier et al. 2019, p. 287.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hotez 2013, p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Despommier et al. 2019, p. 288.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hotez 2013, p. 68.

- ^ "Guinea Worm Disease Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 September 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Guinea Worm - Biology". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Despommier et al. 2019, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pearson RD (September 2020). "Dracunculiasis". Merck Manual. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Management of Guinea Worm Disease". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 May 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Hopkins DR; Ruiz-Tiben E; Downs P; Withers PC Jr.; Maguire JH (2005-10-01). "Dracunculiasis Eradication: The Final Inch". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 73 (4): 669–675. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.669. PMID 16222007.

- ^ Callahan et al. 2013, Introduction.

- ^ Despommier et al. 2019, p. 289.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Spector & Gibson 2016, p. 111.

- ^ Bimi, L.; Freeman, A. R.; Eberhard, M. L.; Ruiz-Tiben, E.; Pieniazek, N. J. (10 May 2005). "Differentiating Dracunculus medinensis from D. insignis, by the sequence analysis of the 18S rRNA gene" (PDF). Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 99 (5): 511–517. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.603.9521. doi:10.1179/136485905x51355. PMID 16004710. S2CID 34119903. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

swas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Number of Reported Cases of Guinea Worm Disease by Year: 1989–2017*" (PDF). Guinea Worm Eradication Program. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ^ WHO 2021, p. 173.

- ^ Despommier et al. 2019, p. 299.

- ^ Spector & Gibson 2016, p. 109.

- ^ Watts S (2000). "Dracunculiasis in the Caribbean and South America:A Contribution to the History of Dracunculiasis Eradication". Med Hist. 44 (2): 227–250. doi:10.1017/s0025727300066412. PMC 1044253. PMID 10829425.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-03. Retrieved 2014-06-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ CDC (2000-10-11). "Progress Toward Global Dracunculiasis Eradication, June 2000". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 49 (32): 731–735. PMID 11411827.

- ^ The Carter Center. "Activities by Country—Guinea Worm Eradication Program". The Carter Center. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

CDCwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Guinea Worm Wrap-up #252" (PDF). The Carter Center. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ "Guinea Worm Disease (Dracunculiasis) Worldwide Case Numbers" (PDF). The Carter Center. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ Donald G. McNeil Jr. (22 March 2018). "South Sudan Halts Spread of Crippling Guinea Worms". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Guinea Worm Disease: Case Countdown". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2014-01-21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Guinea Worm Disease: Case Countdown". Carter Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-19.

- ^ "54* Cases of Guinea Worm Reported in 2019". Carter Center. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ A footnote to the Carter Center press release says it "originally stated that 53 cases of Guinea worm were reported in 2019", but it now reads "54* cases of Guinea worm disease were reported in 2019"; however, the case numbers by country continue to read "47 human cases of the disease were reported in Chad, four in South Sudan, one in Angola, and one in Cameroon that is believed to have been imported from Chad", which adds up to only 53.[50]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Guinea Worm Case Totals". The Carter Center. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Plutarch; Goodwin, William W., ed. (1871). "Symposiacs, Book VIII, Question 9, §. 3". Plutarch's Morals. 3. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Little, Brown, and Co. p. 430.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) From p. 430: "Those that fell sick about the Red Sea, if we believe Agatharcides, besides other strange and unheard diseases, had little serpents in their legs and arms, which did eat their way out, but when touched shrunk in again, and raised intolerable inflammations in the muscles; … "

- ^ Holmes, Oliver Wendell (1952). The Autocrat of the Breakfast Table (1858). London: J.M Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 180. ISBN 1406813176.

- ^ Emerson, John (27 July 2003). "Eradicating Guinea Worm Disease". Social Design Notes. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- ^ See:

- Fedchenko (Федченко), Alexei (Алексей) (1870). "О строении и размножении ришты (Filaria medinensis L.)" [On the structure and reproduction of the Guinea worm (Filaria medinensis L.)]. Известия Императорского Общества Любителей Естествознания, Антропологии и Этнографии [News of the Imperial Society of Devotees of Natural Science, Anthropology and Ethnography (Moscow)] (in Russian). 8 (1): 71–82.

- English translation: Fedchenko, A. P. (1971). "Concerning the structure and reproduction of the guinea-worm (Filaria medinensis L.)". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 20 (4): 511–523. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1971.20.511.

- ^ Христо Стамболски: Автобиография, дневници и mспомени. (Autobiography of Hristo Stambolski. Sofia : Dŭržavna pečatnica, 1927–1931)

- ^ Hopkins et al. 2018, Introduction.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hotez 2013, p. 69.

- ^ "Guinea Worm Infection (Dracunculiasis)". The Imaging of Tropical Diseases. International Society of Radiology. 2008. Archived from the original on November 29, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ "Chad holds annual review; focal distribution of dog infections" (PDF). 17 February 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". WHO. January 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Eberhard, ML; Ruiz-Tiben, E; Hopkins, DR; Farrell, C; Toe, F; Weiss, A; Withers PC, Jr; Jenks, MH; Thiele, EA; Cotton, JA; Hance, Z; Holroyd, N; Cama, VA; Tahir, MA; Mounda, T (January 2014). "The peculiar epidemiology of dracunculiasis in Chad". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 90 (1): 61–70. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0554. PMC 3886430. PMID 24277785.

Works cited[]

- Callahan K, Bolton B, Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Withers PC, Meagley K (30 May 2013). "Contributions of the Guinea Worm Disease eradication campaign toward achievement of the Millennium Development Goals". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002160. PMC 3667764.

- Despommier DD, Griffin DO, Gwadz RW, Hotez PJ, Knirsch CA (2019). "25. Dracunculus medinensis". Parasitic Diseases (PDF) (7 ed.). New York: Parasites Without Borders. p. 201. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Eberhard ML, Weiss A, Withers PC, Roy SL, Sienko DG (August 2018). "Dracunculiasis Eradication: Are We There Yet?". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 99 (2): 388–395. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-0204. PMC 6090361. PMID 29869608.

- Hotez PJ (2013). "The Filarial Infections: Lymphatic Filariasis (Elephantiasis) and Dracunculiasis (Guinea Worm)". Forgotten People, Forgotten Diseases: The Neglected Tropical Diseases and Their Impact on Global Health and Development. ASM Press.

- Spector JM, Gibson TE, eds. (2016). "Dracunculiasis". Atlas of Pediatrics in the Tropics and Resource-Limited Settings (2 ed.). American Academy of Pediatrics. ISBN 978-1-58110-960-3.

- Dracunculiasis Eradication: Global Surveillance Summary, 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

External links[]

- "Guinea Worm Disease Eradication Program". Carter Center.

- Nicholas D. Kristof from the New York Times follows a young Sudanese boy with a Guinea Worm parasite infection who is quarantined for treatment as part of the Carter program

- Tropical Medicine Central Resource: "Guinea Worm Infection (Dracunculiasis)"

- World Health Organization on Dracunculiasis

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Infectious diseases with eradication efforts

- Helminthiases

- Neglected tropical diseases

- Parasitic infestations, stings, and bites of the skin

- Rare infectious diseases

- Tropical diseases

- Waterborne diseases