Early Cornish texts

Specimens of Middle Cornish texts are given here in Cornish and English. Both texts have been dated within the period 1370–1410 and the Charter Fragment is given in two Cornish orthographies. (Earlier examples of written Cornish exist but these are the first in continuous prose or verse.)

Background[]

It was not until the reign of Athelstan that the Cornish kings became subject to the rulers of Wessex: even so the border was established irrevocably on the east bank on the Tamar and in ecclesiastical matters Cornwall was added to the territory of the Bishops of Sherborne. Under Canute it ceased to be subject to the King of England and only later, at an unknown date in Edward the Confessor's reign was annexed again. After the Conquest the Earldom of Wessex was broken up and soon Cornwall was established as a Norman earldom of importance. Cornwall was regarded as a separately named province, with its own subordinated status and title under the English crown, with separate ecclesiastical provision in the earliest phase. There were subsequent constitutional provisions under the Stannary Parliament, which had its origins in provisions of 1198 and 1201 separating the Cornish and Devon tin interests and developing into a separate parliament for Cornwall maintaining Cornish customary law. From 1337, Cornwall was further administered as a 'quasi-sovereign' royal Duchy during the later medieval period.

The implication of these processes for the Cornish language was to ensure its integrity throughout this period. It was until early modern times the general speech of essentially the whole population and all social classes. The situation changed rapidly with the far-reaching political and economic changes from the end of the medieval period onwards. Language-shift from Cornish to English progressed through Cornwall from east to west from this period onwards.

Growth in population continued to a likely peak of 38,000 before the demographic reversal of the Black Death in the 1340s. Thereafter numbers of Cornish speakers were maintained at around 33,000 between the mid-fourteenth and mid-sixteenth centuries against a background of substantial increase in the total Cornish population. From this position the language then inexorably declined until it died out as community speech in parts of Penwith at the end of the eighteenth century.

Linguistic changes[]

During this middle period, Cornish underwent changes in its phonology and morphology. An Old Cornish vocabulary survives from ca. 1100, and manumissions in the Bodmin Gospels from even earlier (ca. 900). Placename elements from this early period have been 'fossilised' in eastern Cornwall as the language changed to English, as likewise did Middle Cornish forms in Mid-Cornwall, and Late Cornish forms in the west. These changes can be used to date the changeover from Cornish to English in local speechways, which together with later documentary evidence enables the areas within which Cornish successively survived to be identified.

Middle Cornish is best represented by the Ordinalia, which comprise a cycle of mystery plays written in Cornish, it is believed at Glasney College, Kerrier, in west Cornwall, between 1350 and 1450, and performed throughout areas where the language was still extant in open-air amphitheatres (playing-places or 'rounds' - plenys-an-gwary in Cornish) which still exist in many places.

There is also a surviving religious poem Pascon agan Arluth (The Passion of Our Lord) which enable a linguistic corpus of Middle Cornish to be ascertained. Later miracle play compositions include: Beunans Meriasek (the Life of St. Meriadoc) datable to 1504; and William Jordan of Helston's Gwreans an Bys (The Creation of the World). These may hark back to older forms of the language, for other writings in the sixteenth century show the language to have been undergoing substantial changes which brought it into its latest surviving form (Late or Modern Cornish). These writings include 's translation of Bishop Bonner's 'Homilies' c. 1556. [1]

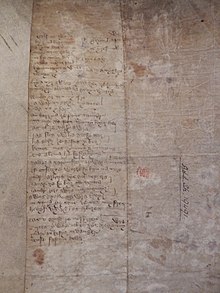

The Charter Fragment, ca. 1400[]

The Charter Fragment is a short poem about marriage, believed to be the earliest extant connected text in the language. It was identified in 1877 by Henry Jenner among charters from Cornwall in the British Museum and published by Jenner and by Whitley Stokes.[1]

Manuscript

1 golsoug ty coweȝ

2 byȝ na borȝ meȝ

3 dyyskyn ha powes

4 ha ȝymo dus nes

5 mar coȝes ȝe les

6 ha ȝys y rof mowes

7 ha fest unan dek

8 genes mar a plek

9 ha, tanha y

10 kymmerr y ȝoȝ wrek

11 sconya ȝys ny vek

12 ha ty a vyȝ hy

13 hy a vyȝ gwreg ty da

14 ȝys ȝe synsy

15 pur wyr a lauara

16 ha govyn worty

17 Lemen yȝ torn my as re

18 ha war an greyȝ my an te

19 nag usy far

20 an barȝ ma ȝe pons tamar

21 my ad pes worty byȝ da

22 ag ol ȝe voȝ hy a wra

23 rag flog yw ha gensy soȝ

24 ha gassy ȝe gafus hy boȝ

25 kenes mos ȝymmo

25a ymmyug

26 eug alema ha fystynyug

27 dallaȝ a var infreȝ dar war

28 oun na porȝo

29 ef emsettye worȝesy

30 kam na veȝo

31 mar aȝ herg ȝys gul nep tra

32 lauar ȝesy byȝ ny venna

33 lauar ȝoȝo gwra mar mennyȝ

34 awos a gallo na wra tra vyȝ

35 in vrna yȝ sens ȝe ves meystres

36 hedyr vywy hag harluȝes

37 cas o ganso re nofferen

38 curtes yw ha deboner

39 ȝys dregyn ny wra

40 mar an kefyȝ in danger

41 sense fast indella

1 Golsow ty goweth

2 Byth na borth meth

3 Diyskynn ha powes

4 Ha dhymmo deus nes

5 Mar kodhes dha les

6 Ha dhis y rov mowes

7 Ha fest onan deg

8 Genes mara pleg

9 A tann hi

10 Kemmer hi dhe'th wreg

11 Skonya dhis ny veg

12 Ha ty a'fydh hi

13 Hi a vydh gwre'ti dha

14 Dhis dhe synsi

15 Pur wir a lavarav

16 ha govynn orti

17 Lemmyn y'th torn my a's re

18 Ha war an gres my a'n te

19 Nag usi hy far

20 A'n barth ma dhe bons Tamar

21 My a'th pys orti bydh da

22 Hag oll dha vodh hi a wra

23 Rag flogh yw ha gensi doeth

24 ha gas hi dhe gavoes hy bodh

25 Kyn es mos dhymmo ymmewgh

26 Ewgh alemma ha fistenewgh

27 Dalleth a-varr yn freth darwar

28 Own na borthho

29 Ev omsettya orthis sy

30 kamm na vedho

31 Mara'th ergh dhis gul neb tra

32 Lavar dhiso byth ny vynnav

33 Lavar dhodho gwrav mar mynnydh

34 Awos a allo ny wra travyth

35 Y'n eur na y'th syns dhe vos mestres

36 Hedra vywi hag arlodhes

37 Kas o ganso re'n Oferenn

38 Kortes yw ha deboner

39 Dhis dregynn ny wra

40 Mara'n kevydh yn danjer

41 Syns ev fast yndella

- Translation

1 Listen friend,

2 Do not be shy!

3 Come down and rest

4 and come closer to me

5 if you know what is to your advantage,

6 and I will give you a girl,

7 one who is very beautiful.

8 If you like her,

9 go and get her;

10 take her for your wife.

11 She will not murmur to refuse you

12 and you will have her

13 She will be a good wife

14 to keep house for you.

15 I tell you the complete truth.

16 Go and ask her

17 Now I give her into your hand

18 and on the Creed I swear

19 there is not her equal

20 from here to the Tamar Bridge.

21 I beg you to be good to her

22 and she will all you want,

23 for she is a child and truthful withal.

24 Go and let her have her own way.

25 Before going,

25a have a kiss for me!

26 Go away and be quick!

27 Begin promptly, eagerly. Take care

28 to make him nervous

29 so that he dare not

30 oppose you at all.

31 If he bids you do something,

32 say to yourself, "I never will."

33 Say to him "I will do it if you wish."

34 For all he can, he will do nothing.

35 Then he will esteem you as Mistress

36 and Lady as long as you live.

37 He was troubled, by the Mass.

38 Courteous and kind is he

39 He will not do you any harm

40 If you (can) enthral him

41 hold him tightly so!

Pascon agan Arluth—The Passion Poem—Mount Calvary[]

Pascon agan Arluth ('The Passion of our Lord'), a poem of 259 eight-line verses probably composed around 1375, is one of the earliest surviving works of Cornish literature. Five manuscripts are known to exist, the earliest dating to the 15th century.[2]

References[]

- Middle Cornish literature

- Christianity in Cornwall