Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation (Memling)

| Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Hans Memling |

| Year | circa 1485 |

| Medium | oil painting on wood panel (oak) |

| Movement | Early Netherlandish painting Catholic art |

| Subject | Vanity or Lust Death Hell Memento mori Christ in Majesty/Salvator Mundi Coat of arms |

| Dimensions | 20 cm × 13 cm (7.9 in × 5.1 in); average measurement; millimetric differences exist between some of the six panels[1] |

| Location | Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg |

| Accession | 1890 |

Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation is a 1480s painting by the German-born citizen of Bruges, Hans Memling. It is on display in the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Strasbourg, France. Its inventory number is 185.[2]

Overview[]

The work consists of six isolated panels which had originally been arranged recto-verso as pairs and were sawn apart at some point before 1890. Neither the order of the panels from left to right, nor the coupling of the pairs of paintings, is known with certainty; and because of the work's theological content, it is disputed if it was designed as a triptych or as a polyptych. Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation has generally risen and still raises more questions among art historians than almost any other work of its century, or any century.[1] As it exists now, Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation consists of a narrative sequence (Vanity is followed by Death, which is followed either by Hell or by the Redemption through Jesus; this is framed by a general memento mori and a particular coat of arms). But this sequence may well be incomplete or not entirely reflect the intended purpose: for instance, Vanity may also be a depiction of Luxuria, etc.

Question of attribution[]

The attribution of the work has been disputed. In 1890, Wilhelm von Bode bought it in Florence, Italy, as a Memling, but as early as 1892, he attributed it to Memling's contemporary, Simon Marmion. This attribution was kept by some specialists, while several others – such as Hugo von Tschudi, Georges Hulin de Loo, and Max J. Friedlander – maintained that it was indeed a Memling; of the late period and of very high quality as far as Friedlander was concerned. The debate later shifted on the question of authenticity: it was questioned if it was a painting by Memling himself, or rather by an assistant, a follower, or an imitator. The question has been settled since 1994, when thorough examination showed that it was indeed a genuine work by Hans Memling himself.[1]

Question of destination[]

The destination of the work has been just as disputed. The coat of arms had been attributed to several Italian families, until Hulin de Loo identified it as the Loiani family crest. The work may have been commissioned by Giovanni d′Antonio Loiano, from Bologna, who had married a Flemish woman. It remains unresolved if the work was as it is now, i.e. a triptych, or if a recto-verso panel has been lost and the work had originally been a polyptych. This hypothesis in turn raises the question of the painterly subjects on either side of the lost panel. Moreover, as it could be closed (as a triptych), or folded (as a polyptych), there is no certainty as to the order in which the paintings were shown in either state. Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation was probably used for private devotion, as a domestic altarpiece that could also be carried with its owner.[1][2]

Question of iconography[]

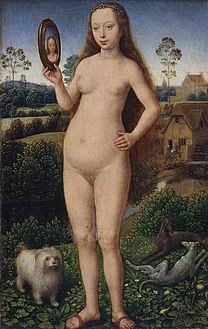

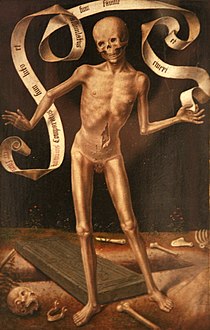

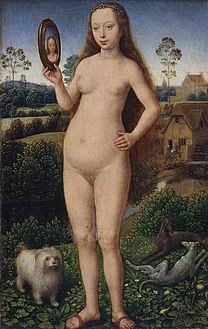

The iconographic program of Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation is complex, although not impenetrably so, hence the title given to the work. The proponents of the theory that a fourth recto-verso panel is missing suggest that it could have shown the Virgin Mary (responding to her son depicted as a Salvator Mundi but also with attributes of a Christ in Majesty, such as the crown) on one side, and Adam on the other (responding to Eve, depicted as the allegorical figure of Vanity). The purposes of Death, Hell, Memento mori, and the coat of arms, are quite clear, although their position is not. Vanity (which may also represent Luxuria) and Death share aesthetic and thematic parallels, not least in the very prominent genital area, a fact that has prompted the tenants of the triptych hypothesis to dismiss the idea that Vanity/Luxuria should have been paired with another painting instead. On the other hand, the probable pairing of Christ with Hell is theologically untenable; as in Memling’s own Last Judgment, depictions of Hell are generally paired with depictions of Heaven.[1]

Satan's face on the belly () has been noticed by art historians,[3] as has Vanity's/Luxuria's eroticism.[4][5]

Possible pairings[]

The following pairings have been suggested as being the most plausible:[1]

As a triptych:

- Memento mori – Hell

- Vanity/Luxuria – Christ in Majesty/Salvator Mundi

- Death – Coat of arms

As a polyptych:

- Memento mori – Hell

- Christ in Majesty/Salvator Mundi – Vanity/Luxuria

- Virgin Mary – unknown subject [the missing panel]

- Coat of arms – Death

In both cases, only Vanity and Death appear together on the same side, while Hell and Christ, and Hell and Death, and even Memento mori and Coat of arms appear once on the same side, and once on opposite sides.

Gallery[]

Vanity, or Luxuria

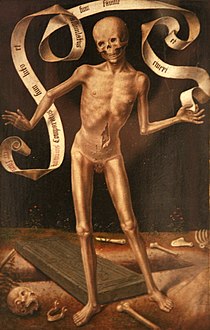

Death. The text says: Ecce finis hominis comparatus sum luto et assimilatus sum faville et cineri ("This is the end of Man; I am like mud [or clay] and I return to dust and ashes")

Christ in Majesty/Salvator Mundi

Coat of arms. The text says: Nul bien sans peine ("No good without effort" or "No pain, no gain")

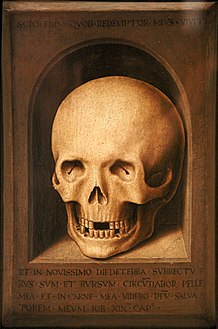

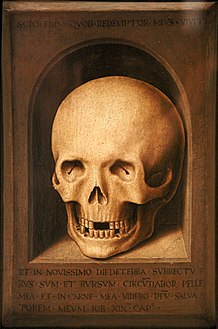

Memento mori. The text says: Scio enim quod redemptor meus vivit et in novissimo diedeterra surrecturus sum et rursum circūdabor pelle mea et incarne mea videbo deū salvaorem meum Job XIX° cap° ("For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth. And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God", Book of Job 19, 25-26 (KJV))

Hell. The text says: In inferno, nulla est redemptio ("There is no redemption in Hell")

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f Monfort, Marie (February 2009). Collection du musée des Beaux-Arts – Peinture flamande et hollandaise XVème-XVIIIème siècle. Strasbourg: Musées de la ville de Strasbourg. pp. 51–55. ISBN 978-2-35125-030-3.

- ^ a b Jacquot, Dominique (2006). Le musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg. Cinq siècles de peinture. Strasbourg: Musées de Strasbourg. pp. 32–39. ISBN 2-901833-78-0.

- ^ Cumming, Laura. "The 10 best scary paintings". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Gayford, Martin. "Full of lovely paintings that might lead you astray: The Renaissance Nude reviewed". The Spectator. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Norén, Laura. "Ways of Seeing by John Berger". The Society Pages. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polyptych of earthly vanities and heavenly redemption (Strasbourg). |

- Polyptyque de la Vanité terrestre et de la Rédemption céleste, presentation on the museum's website

- Piorko, Megan: Nothing Good without Pain: Hans Memling's Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation, Spring 2014 MA thesis, Georgia State University.[A]

Notes[]

A Piorko's MA thesis contains some small errata. It references the 2009 book Collection du musée des Beaux-Arts – Peinture flamande et hollandaise XVème-XVIIIème siècle but erroneously quotes pages 49–53 instead of 51–55. It also consistently misspells memento mori as "momento mori".

- 1480s paintings

- Paintings by Hans Memling

- Paintings in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg

- Skulls in art

- Triptychs

- Polyptychs

- Angels in art

- Dogs in art

- Paintings depicting Jesus

- Musical instruments in art

- 15th-century allegorical paintings