Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe | |

|---|---|

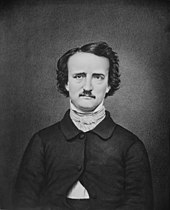

1849 "Annie" daguerreotype of Poe | |

| Born | Edgar Poe January 19, 1809 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | October 7, 1849 (aged 40) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Virginia United States Military Academy |

| Spouse | Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe

(m. 1836; died 1847) |

| Signature |  |

Edgar Allan Poe (/poʊ/; born Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is widely regarded as a central figure of Romanticism in the United States and of American literature as a whole, and he was one of the country's earliest practitioners of the short story. He is also generally considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre and is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction.[1] Poe was the first well-known American writer to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.[2]

Poe was born in Boston, the second child of actors David and Elizabeth "Eliza" Poe.[3] His father abandoned the family in 1810, and his mother died the following year. Thus orphaned, Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan of Richmond, Virginia. They never formally adopted him, but he was with them well into young adulthood. Tension developed later as Poe and John Allan repeatedly clashed over Poe's debts, including those incurred by gambling, and the cost of Poe's education. Poe attended the University of Virginia but left after a year due to lack of money. He quarreled with Allan over the funds for his education and enlisted in the United States Army in 1827 under an assumed name. It was at this time that his publishing career began with the anonymous collection Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), credited only to "a Bostonian". Poe and Allan reached a temporary rapprochement after the death of Allan's wife in 1829. Poe later failed as an officer cadet at West Point, declaring a firm wish to be a poet and writer, and he ultimately parted ways with Allan.

Poe switched his focus to prose and spent the next several years working for literary journals and periodicals, becoming known for his own style of literary criticism. His work forced him to move among several cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. He married his 13-year-old cousin, Virginia Clemm, in 1836, but Virginia died of tuberculosis in 1847. In January 1845, Poe published his poem "The Raven" to instant success. He planned for years to produce his own journal The Penn (later renamed The Stylus), but before it could be produced, he died in Baltimore on October 7, 1849, at age 40. The cause of his death is unknown and has been variously attributed to disease, alcoholism, substance abuse, suicide, and other causes.[4]

Poe and his works influenced literature around the world, as well as specialized fields such as cosmology and cryptography. He and his work appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, and television. A number of his homes are dedicated museums today. The Mystery Writers of America present an annual award known as the Edgar Award for distinguished work in the mystery genre.

Early life

Edgar Poe was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1809, the second child of English-born actress Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe and actor David Poe Jr. He had an elder brother named William Henry Leonard Poe and a younger sister named Rosalie Poe.[5] Their grandfather, David Poe Sr., emigrated from County Cavan, Ireland, around 1750.[6] Edgar may have been named after a character in William Shakespeare's King Lear, which the couple were performing in 1809.[7] His father abandoned the family in 1810,[8] and his mother died a year later from consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis). Poe was then taken into the home of John Allan, a successful merchant in Richmond, Virginia, who dealt in a variety of goods, including cloth, wheat, tombstones, tobacco, and slaves.[9] The Allans served as a foster family and gave him the name "Edgar Allan Poe",[10] though they never formally adopted him.[11]

The Allan family had Poe baptized into the Episcopal Church in 1812. John Allan alternately spoiled and aggressively disciplined his foster son.[10] The family sailed to the United Kingdom in 1815, and Poe attended the grammar school for a short period in Irvine, Ayrshire, Scotland (where Allan was born) before rejoining the family in London in 1816. There he studied at a boarding school in Chelsea until summer 1817. He was subsequently entered at the Reverend John Bransby's Manor House School at Stoke Newington, then a suburb 4 miles (6 km) north of London.[12]

Poe moved with the Allans back to Richmond in 1820. In 1824, he served as the lieutenant of the Richmond youth honor guard as the city celebrated the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette.[13] In March 1825, Allan's uncle and business benefactor William Galt died, who was said to be one of the wealthiest men in Richmond,[14] leaving Allan several acres of real estate. The inheritance was estimated at $750,000 (equivalent to $17,000,000 in 2020).[15] By summer 1825, Allan celebrated his expansive wealth by purchasing a two-story brick house called Moldavia.[16]

Poe may have become engaged to Sarah Elmira Royster before he registered at the University of Virginia in February 1826 to study ancient and modern languages.[17][18] The university was in its infancy, established on the ideals of its founder Thomas Jefferson. It had strict rules against gambling, horses, guns, tobacco, and alcohol, but these rules were mostly ignored. Jefferson had enacted a system of student self-government, allowing students to choose their own studies, make their own arrangements for boarding, and report all wrongdoing to the faculty. The unique system was still in chaos, and there was a high dropout rate.[19] During his time there, Poe lost touch with Royster and also became estranged from his foster father over gambling debts. He claimed that Allan had not given him sufficient money to register for classes, purchase texts, and procure and furnish a dormitory. Allan did send additional money and clothes, but Poe's debts increased.[20] Poe gave up on the university after a year but did not feel welcome returning to Richmond, especially when he learned that his sweetheart Royster had married another man, Alexander Shelton. He traveled to Boston in April 1827, sustaining himself with odd jobs as a clerk and newspaper writer,[21] and he started using the pseudonym Henri Le Rennet during this period.[22]

Military career

Poe was unable to support himself, so he enlisted in the United States Army as a private on May 27, 1827, using the name "Edgar A. Perry". He claimed that he was 22 years old even though he was 18.[23] He first served at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor for five dollars a month.[21] That same year, he released his first book, a 40-page collection of poetry titled Tamerlane and Other Poems, attributed with the byline "by a Bostonian". Only 50 copies were printed, and the book received virtually no attention.[24] Poe's regiment was posted to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina and traveled by ship on the brig Waltham on November 8, 1827. Poe was promoted to "artificer", an enlisted tradesman who prepared shells for artillery, and had his monthly pay doubled.[25] He served for two years and attained the rank of Sergeant Major for Artillery (the highest rank that a non-commissioned officer could achieve); he then sought to end his five-year enlistment early. Poe revealed his real name and his circumstances to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Howard, who would only allow Poe to be discharged if he reconciled with Allan. Poe wrote a letter to Allan, who was unsympathetic and spent several months ignoring Poe's pleas; Allan may not have written to Poe even to make him aware of his foster mother's illness. Frances Allan died on February 28, 1829, and Poe visited the day after her burial. Perhaps softened by his wife's death, Allan agreed to support Poe's attempt to be discharged in order to receive an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.[26]

Poe was finally discharged on April 15, 1829, after securing a replacement to finish his enlisted term for him.[27] Before entering West Point, he moved back to Baltimore for a time to stay with his widowed aunt Maria Clemm, her daughter Virginia Eliza Clemm (Poe's first cousin), his brother Henry, and his invalid grandmother Elizabeth Cairnes Poe.[28] In September of that year, Poe received "the very first words of encouragement I ever remember to have heard"[29] in a review of his poetry by influential critic John Neal, prompting Poe to dedicate one of the poems to Neal[30] in his second book Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems, published in Baltimore in 1829.[31]

Poe traveled to West Point and matriculated as a cadet on July 1, 1830.[32] In October 1830, Allan married his second wife Louisa Patterson.[33] The marriage and bitter quarrels with Poe over the children born to Allan out of extramarital affairs led to the foster father finally disowning Poe.[34] Poe decided to leave West Point by purposely getting court-martialed. On February 8, 1831, he was tried for gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders for refusing to attend formations, classes, or church. He tactically pleaded not guilty to induce dismissal, knowing that he would be found guilty.[35]

Poe left for New York in February 1831 and released a third volume of poems, simply titled Poems. The book was financed with help from his fellow cadets at West Point, many of whom donated 75 cents to the cause, raising a total of $170. They may have been expecting verses similar to the satirical ones that Poe had been writing about commanding officers.[36] It was printed by Elam Bliss of New York, labeled as "Second Edition," and including a page saying, "To the U.S. Corps of Cadets this volume is respectfully dedicated". The book once again reprinted the long poems "Tamerlane" and "Al Aaraaf" but also six previously unpublished poems, including early versions of "To Helen", "Israfel", and "The City in the Sea".[37] Poe returned to Baltimore to his aunt, brother, and cousin in March 1831. His elder brother Henry had been in ill health, in part due to problems with alcoholism, and he died on August 1, 1831.[38]

Publishing career

After his brother's death, Poe began more earnest attempts to start his career as a writer, but he chose a difficult time in American publishing to do so.[39] He was one of the first Americans to live by writing alone[2][40] and was hampered by the lack of an international copyright law.[41] American publishers often produced unauthorized copies of British works rather than paying for new work by Americans.[40] The industry was also particularly hurt by the Panic of 1837.[42] There was a booming growth in American periodicals around this time, fueled in part by new technology, but many did not last beyond a few issues.[43] Publishers often refused to pay their writers or paid them much later than they promised,[44] and Poe repeatedly resorted to humiliating pleas for money and other assistance.[45]

After his early attempts at poetry, Poe had turned his attention to prose, likely based on John Neal's critiques in The Yankee magazine.[46] He placed a few stories with a Philadelphia publication and began work on his only drama Politian. The Baltimore Saturday Visiter awarded him a prize in October 1833 for his short story "MS. Found in a Bottle".[47] The story brought him to the attention of John P. Kennedy, a Baltimorean of considerable means who helped Poe place some of his stories and introduced him to Thomas W. White, editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond. Poe became assistant editor of the periodical in August 1835,[48] but White discharged him within a few weeks for being drunk on the job.[49] Poe returned to Baltimore where he obtained a license to marry his cousin Virginia on September 22, 1835, though it is unknown if they were married at that time.[50] He was 26 and she was 13.

Poe was reinstated by White after promising good behavior, and he went back to Richmond with Virginia and her mother. He remained at the Messenger until January 1837. During this period, Poe claimed that its circulation increased from 700 to 3,500.[5] He published several poems, book reviews, critiques, and stories in the paper. On May 16, 1836, he and Virginia held a Presbyterian wedding ceremony at their Richmond boarding house, with a witness falsely attesting Clemm's age as 21.[50][51]

Poe's novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket was published and widely reviewed in 1838.[52] In the summer of 1839, Poe became assistant editor of Burton's Gentleman's Magazine. He published numerous articles, stories, and reviews, enhancing his reputation as a trenchant critic which he had established at the Messenger. Also in 1839, the collection Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque was published in two volumes, though he made little money from it and it received mixed reviews.[53]

In June 1840, Poe published a prospectus announcing his intentions to start his own journal called The Stylus,[54] although he originally intended to call it The Penn, as it would have been based in Philadelphia. He bought advertising space for his prospectus in the June 6, 1840 issue of Philadelphia's Saturday Evening Post: "Prospectus of the Penn Magazine, a Monthly Literary journal to be edited and published in the city of Philadelphia by Edgar A. Poe."[55] The journal was never produced before Poe's death.

Poe left Burton's after about a year and found a position as writer and co-editor at the then-very-successful monthly Graham's Magazine.[56] In the last number of Graham's for 1841, Poe was among the co-signatories to an editorial note of celebration of the tremendous success that magazine had achieved in the past year: "Perhaps the editors of no magazine, either in America or in Europe, ever sat down, at the close of a year, to contemplate the progress of their work with more satisfaction than we do now. Our success has been unexampled, almost incredible. We may assert without fear of contradiction that no periodical ever witnessed the same increase during so short a period."[57]

Around this time, Poe attempted to secure a position within the administration of President John Tyler, claiming that he was a member of the Whig Party.[58] He hoped to be appointed to the United States Custom House in Philadelphia with help from President Tyler's son Robert,[59] an acquaintance of Poe's friend Frederick Thomas.[60] Poe failed to show up for a meeting with Thomas to discuss the appointment in mid-September 1842, claiming to have been sick, though Thomas believed that he had been drunk.[61] Poe was promised an appointment, but all positions were filled by others.[62]

One evening in January 1842, Virginia showed the first signs of consumption, now known as tuberculosis, while singing and playing the piano, which Poe described as breaking a blood vessel in her throat.[63] She only partially recovered, and Poe began to drink more heavily under the stress of her illness. He left Graham's and attempted to find a new position, for a time angling for a government post. He returned to New York where he worked briefly at the Evening Mirror before becoming editor of the Broadway Journal, and later its owner.[64] There Poe alienated himself from other writers by publicly accusing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of plagiarism, though Longfellow never responded.[65] On January 29, 1845, his poem "The Raven" appeared in the Evening Mirror and became a popular sensation. It made Poe a household name almost instantly,[66] though he was paid only $9 for its publication.[67] It was concurrently published in The American Review: A Whig Journal under the pseudonym "Quarles".[68]

The Broadway Journal failed in 1846,[64] and Poe moved to a cottage in Fordham, New York, in what is now the Bronx. That home is now known as the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage, relocated to a park near the southeast corner of the Grand Concourse and Kingsbridge Road. Nearby, Poe befriended the Jesuits at St. John's College, now Fordham University.[69] Virginia died at the cottage on January 30, 1847.[70] Biographers and critics often suggest that Poe's frequent theme of the "death of a beautiful woman" stems from the repeated loss of women throughout his life, including his wife.[71]

Poe was increasingly unstable after his wife's death. He attempted to court poet Sarah Helen Whitman who lived in Providence, Rhode Island. Their engagement failed, purportedly because of Poe's drinking and erratic behavior. There is also strong evidence that Whitman's mother intervened and did much to derail their relationship.[72] Poe then returned to Richmond and resumed a relationship with his childhood sweetheart Sarah Elmira Royster.[73]

Death

On October 3, 1849, Poe was found delirious on the streets of Baltimore, "in great distress, and… in need of immediate assistance", according to Joseph W. Walker, who found him.[74] He was taken to the Washington Medical College, where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849, at 5:00 in the morning.[75] Poe was not coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition and was wearing clothes that were not his own. He is said to have repeatedly called out the name "Reynolds" on the night before his death, though it is unclear to whom he was referring. Some sources say that Poe's final words were, "Lord help my poor soul".[75] All medical records have been lost, including Poe's death certificate.[76]

Newspapers at the time reported Poe's death as "congestion of the brain" or "cerebral inflammation", common euphemisms for death from disreputable causes such as alcoholism.[77] The actual cause of death remains a mystery.[78] Speculation has included delirium tremens, heart disease, epilepsy, syphilis, meningeal inflammation,[4] cholera,[79] carbon monoxide poisoning,[80] and rabies.[81] One theory dating from 1872 suggests that cooping was the cause of Poe's death, a form of electoral fraud in which citizens were forced to vote for a particular candidate, sometimes leading to violence and even murder.[82]

Griswold's "Memoir"

Immediately after Poe's death, his literary rival Rufus Wilmot Griswold wrote a slanted high-profile obituary under a pseudonym, filled with falsehoods that cast him as a lunatic and a madman, and which described him as a person who "walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayers, (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned)".[83]

The long obituary appeared in the New York Tribune signed "Ludwig" on the day that Poe was buried. It was soon further published throughout the country. The piece began, "Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it."[84] "Ludwig" was soon identified as Griswold, an editor, critic, and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842. Griswold somehow became Poe's literary executor and attempted to destroy his enemy's reputation after his death.[85]

Griswold wrote a biographical article of Poe called "Memoir of the Author", which he included in an 1850 volume of the collected works. There he depicted Poe as a depraved, drunken, drug-addled madman and included Poe's letters as evidence.[85] Many of his claims were either lies or distortions; for example, it is seriously disputed that Poe was a drug addict.[86] Griswold's book was denounced by those who knew Poe well,[87] including John Neal, who published an article defending Poe and attacking Griswold as a "Rhadamanthus, who is not to be bilked of his fee, a thimble-full of newspaper notoriety".[88] Griswold's book nevertheless became a popularly accepted biographical source. This was in part because it was the only full biography available and was widely reprinted, and in part because readers thrilled at the thought of reading works by an "evil" man.[89] Letters that Griswold presented as proof were later revealed as forgeries.[90]

Literary style and themes

Genres

Poe's best known fiction works are Gothic,[91] adhering to the genre's conventions to appeal to the public taste.[92] His most recurring themes deal with questions of death, including its physical signs, the effects of decomposition, concerns of premature burial, the reanimation of the dead, and mourning.[93] Many of his works are generally considered part of the dark romanticism genre, a literary reaction to transcendentalism[94] which Poe strongly disliked.[95] He referred to followers of the transcendental movement as "Frog-Pondians", after the pond on Boston Common,[96][97] and ridiculed their writings as "metaphor—run mad,"[98] lapsing into "obscurity for obscurity's sake" or "mysticism for mysticism's sake".[95] Poe once wrote in a letter to Thomas Holley Chivers that he did not dislike transcendentalists, "only the pretenders and sophists among them".[99]

Beyond horror, Poe also wrote satires, humor tales, and hoaxes. For comic effect, he used irony and ludicrous extravagance, often in an attempt to liberate the reader from cultural conformity.[92] "Metzengerstein" is the first story that Poe is known to have published[100] and his first foray into horror, but it was originally intended as a burlesque satirizing the popular genre.[101] Poe also reinvented science fiction, responding in his writing to emerging technologies such as hot air balloons in "The Balloon-Hoax".[102]

Poe wrote much of his work using themes aimed specifically at mass-market tastes.[103] To that end, his fiction often included elements of popular pseudosciences, such as phrenology[104] and physiognomy.[105]

Literary theory

Poe's writing reflects his literary theories, which he presented in his criticism and also in essays such as "The Poetic Principle".[106] He disliked didacticism[107] and allegory,[108] though he believed that meaning in literature should be an undercurrent just beneath the surface. Works with obvious meanings, he wrote, cease to be art.[109] He believed that work of quality should be brief and focus on a specific single effect.[106] To that end, he believed that the writer should carefully calculate every sentiment and idea.[110]

Poe describes his method in writing "The Raven" in the essay "The Philosophy of Composition", and he claims to have strictly followed this method. It has been questioned whether he really followed this system, however. T. S. Eliot said: "It is difficult for us to read that essay without reflecting that if Poe plotted out his poem with such calculation, he might have taken a little more pains over it: the result hardly does credit to the method."[111] Biographer Joseph Wood Krutch described the essay as "a rather highly ingenious exercise in the art of rationalization".[112]

Legacy

Influence

During his lifetime, Poe was mostly recognized as a literary critic. Fellow critic James Russell Lowell called him "the most discriminating, philosophical, and fearless critic upon imaginative works who has written in America", suggesting—rhetorically—that he occasionally used prussic acid instead of ink.[113] Poe's caustic reviews earned him the reputation of being a "tomahawk man".[114] A favorite target of Poe's criticism was Boston's acclaimed poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was often defended by his literary friends in what was later called "The Longfellow War". Poe accused Longfellow of "the heresy of the didactic", writing poetry that was preachy, derivative, and thematically plagiarized.[115] Poe correctly predicted that Longfellow's reputation and style of poetry would decline, concluding, "We grant him high qualities, but deny him the Future".[116]

Poe was also known as a writer of fiction and became one of the first American authors of the 19th century to become more popular in Europe than in the United States.[117] Poe is particularly respected in France, in part due to early translations by Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire's translations became definitive renditions of Poe's work throughout Europe.[118]

Poe's early detective fiction tales featuring C. Auguste Dupin laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle said, "Each [of Poe's detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed.... Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?"[119] The Mystery Writers of America have named their awards for excellence in the genre the "Edgars".[120] Poe's work also influenced science fiction, notably Jules Verne, who wrote a sequel to Poe's novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket called An Antarctic Mystery, also known as The Sphinx of the Ice Fields.[121] Science fiction author H. G. Wells noted, "Pym tells what a very intelligent mind could imagine about the south polar region a century ago".[122] In 2013, The Guardian cited Pym as one of the greatest novels ever written in the English language, and noted its influence on later authors such as Doyle, Henry James, B. Traven, and David Morrell.[123]

Horror author and historian H. P. Lovecraft was heavily influenced by Poe's horror tales, dedicating an entire section of his long essay, "Supernatural Horror in Literature", to his influence on the genre. In his letters, Lovecraft stated, "When I write stories, Edgar Allan Poe is my model."[124] Alfred Hitchcock once said, "It's because I liked Edgar Allan Poe's stories so much that I began to make suspense films".[125]

Like many famous artists, Poe's works have spawned imitators.[126] One trend among imitators of Poe has been claims by clairvoyants or psychics to be "channeling" poems from Poe's spirit. One of the most notable of these was Lizzie Doten, who published Poems from the Inner Life in 1863, in which she claimed to have "received" new compositions by Poe's spirit. The compositions were re-workings of famous Poe poems such as "The Bells", but which reflected a new, positive outlook.[127]

Even so, Poe has also received criticism. This is partly because of the negative perception of his personal character and its influence upon his reputation.[117] William Butler Yeats was occasionally critical of Poe and once called him "vulgar".[128] Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson reacted to "The Raven" by saying, "I see nothing in it",[129] and derisively referred to Poe as "the jingle man".[130] Aldous Huxley wrote that Poe's writing "falls into vulgarity" by being "too poetical"—the equivalent of wearing a diamond ring on every finger.[131]

It is believed that only twelve copies have survived of Poe's first book Tamerlane and Other Poems. In December 2009, one copy sold at Christie's auctioneers in New York City for $662,500, a record price paid for a work of American literature.[132]

Physics and cosmology

Eureka: A Prose Poem, an essay written in 1848, included a cosmological theory that presaged the Big Bang theory by 80 years,[133][134] as well as the first plausible solution to Olbers' paradox.[135][136] Poe eschewed the scientific method in Eureka and instead wrote from pure intuition.[137] For this reason, he considered it a work of art, not science,[137] but insisted that it was still true[138] and considered it to be his career masterpiece.[139] Even so, Eureka is full of scientific errors. In particular, Poe's suggestions ignored Newtonian principles regarding the density and rotation of planets.[140]

Cryptography

Poe had a keen interest in cryptography. He had placed a notice of his abilities in the Philadelphia paper Alexander's Weekly (Express) Messenger, inviting submissions of ciphers which he proceeded to solve.[141] In July 1841, Poe had published an essay called "A Few Words on Secret Writing" in Graham's Magazine. Capitalizing on public interest in the topic, he wrote "The Gold-Bug" incorporating ciphers as an essential part of the story.[142] Poe's success with cryptography relied not so much on his deep knowledge of that field (his method was limited to the simple substitution cryptogram) as on his knowledge of the magazine and newspaper culture. His keen analytical abilities, which were so evident in his detective stories, allowed him to see that the general public was largely ignorant of the methods by which a simple substitution cryptogram can be solved, and he used this to his advantage.[141] The sensation that Poe created with his cryptography stunts played a major role in popularizing cryptograms in newspapers and magazines.[143]

Two ciphers he published in 1841 under the name "W. B. Tyler" were not solved until 1992 and 2000 respectively. One was a quote from Joseph Addison's play Cato; the other is probably based on a poem by Hester Thrale.[144][145]

Poe had an influence on cryptography beyond increasing public interest during his lifetime. William Friedman, America's foremost cryptologist, was heavily influenced by Poe.[146] Friedman's initial interest in cryptography came from reading "The Gold-Bug" as a child, an interest that he later put to use in deciphering Japan's PURPLE code during World War II.[147]

In popular culture

As a character

The historical Edgar Allan Poe has appeared as a fictionalized character, often representing the "mad genius" or "tormented artist" and exploiting his personal struggles.[148] Many such depictions also blend in with characters from his stories, suggesting that Poe and his characters share identities.[149] Often, fictional depictions of Poe use his mystery-solving skills in such novels as The Poe Shadow by Matthew Pearl.[150]

Preserved homes, landmarks, and museums

No childhood home of Poe is still standing, including the Allan family's Moldavia estate. The oldest standing home in Richmond, the Old Stone House, is in use as the Edgar Allan Poe Museum, though Poe never lived there. The collection includes many items that Poe used during his time with the Allan family, and also features several rare first printings of Poe works. 13 West Range is the dorm room that Poe is believed to have used while studying at the University of Virginia in 1826; it is preserved and available for visits. Its upkeep is now overseen by a group of students and staff known as the Raven Society.[151]

The earliest surviving home in which Poe lived is in Baltimore, preserved as the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum. Poe is believed to have lived in the home at the age of 23 when he first lived with Maria Clemm and Virginia (as well as his grandmother and possibly his brother William Henry Leonard Poe).[152] It is open to the public and is also the home of the Edgar Allan Poe Society. Of the several homes that Poe, his wife Virginia, and his mother-in-law Maria rented in Philadelphia, only the last house has survived. The Spring Garden home, where the author lived in 1843–1844, is today preserved by the National Park Service as the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site.[153] Poe's final home is preserved as the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage in the Bronx.[70]

In Boston, a commemorative plaque on Boylston Street is several blocks away from the actual location of Poe's birth.[154][155][156][157] The house which was his birthplace at 62 Carver Street no longer exists; also, the street has since been renamed "Charles Street South".[158][157] A "square" at the intersection of Broadway, Fayette, and Carver Streets had once been named in his honor,[159] but it disappeared when the streets were rearranged. In 2009, the intersection of Charles and Boylston Streets (two blocks north of his birthplace) was designated "Edgar Allan Poe Square".[160]

In March 2014, fundraising was completed for construction of a permanent memorial sculpture, known as Poe Returning to Boston, at this location. The winning design by Stefanie Rocknak depicts a life-sized Poe striding against the wind, accompanied by a flying raven; his suitcase lid has fallen open, leaving a "paper trail" of literary works embedded in the sidewalk behind him.[161][162][163] The public unveiling on October 5, 2014 was attended by former U.S. poet laureate Robert Pinsky.[164]

Other Poe landmarks include a building on the Upper West Side where Poe temporarily lived when he first moved to New York. A plaque suggests that Poe wrote "The Raven" here. On Sullivan's Island in Charleston, South Carolina, the setting of Poe's tale "The Gold-Bug" and where Poe served in the Army in 1827 at Fort Moultrie, there is a restaurant called Poe's Tavern. In Fell's Point, Baltimore, a bar still stands where legend says that Poe was last seen drinking before his death. Now known as "The Horse You Came in On", local lore insists that a ghost whom they call "Edgar" haunts the rooms above.[165]

Photographs

Early daguerreotypes of Poe continue to arouse great interest among literary historians.[166] Notable among them are:

- "Ultima Thule" ("far discovery") to honor the new photographic technique; taken in November 1848 in Providence, Rhode Island, probably by Edwin H. Manchester

- "Annie", given to Poe's friend Annie L. Richmond; probably taken in June 1849 in Lowell, Massachusetts, photographer unknown

Poe Toaster

Between 1949 and 2009, a bottle of cognac and three roses were left at Poe's original grave marker every January 19 by an unknown visitor affectionately referred to as the "Poe Toaster". Sam Porpora was a historian at the Westminster Church in Baltimore where Poe is buried, and he claimed on August 15, 2007, that he had started the tradition in 1949. Porpora said that the tradition began in order to raise money and enhance the profile of the church. His story has not been confirmed,[167] and some details which he gave to the press are factually inaccurate.[168] The Poe Toaster's last appearance was on January 19, 2009, the day of Poe's bicentennial.[169]

List of selected works

|

Short stories

|

Poetry

|

Other works

- Politian (1835) – Poe's only play

- The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) – Poe's only complete novel

- The Journal of Julius Rodman (1840) – Poe's second, unfinished novel

- "The Balloon-Hoax" (1844) – A journalistic hoax printed as a true story

- "The Philosophy of Composition" (1846) – Essay

- Eureka: A Prose Poem (1848) – Essay

- "The Poetic Principle" (1848) – Essay

- "The Light-House" (1849) – Poe's last, incomplete work

See also

- Edgar Allan Poe and music

- Edgar Allan Poe in television and film

- Edgar Allan Poe in popular culture

- List of coupled cousins

- USS E.A. Poe (IX-103)

References

Citations

- ^ Stableford 2003, pp. 18–19

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyers 1992, p. 138

- ^ Semtner, Christopher P. (2012). Edgar Allan Poe's Richmond : the Raven in the River City. Charleston [SC]: History Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-60949-607-4. OCLC 779472206.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyers 1992, p. 256

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allen 1927

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 13

- ^ Nelson 1981, p. 65

- ^ Canada 1997

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 8

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyers 1992, p. 9

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 61

- ^ Silverman 1991, pp. 16–18

- ^ PoeMuseum.org 2006

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 20

- ^ 1634 to 1699: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy ofthe United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700-1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How much is that in real money?: a historical price index for use as a deflator of money values in the economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ Silverman 1991, pp. 27–28

- ^ Silverman 1991, pp. 29–30

- ^ University of Virginia. A Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia. Second Session, Commencing February 1st, 1826. Charlottesville, VA: Chronicle Steam Book Printing House, 1880, p. 10

- ^ Meyers 1992, pp. 21–22

- ^ Silverman 1991, pp. 32–34

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyers 1992, p. 32

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 41

- ^ Cornelius 2002, p. 13

- ^ Meyers 1992, pp. 33–34

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 35

- ^ Silverman 1991, pp. 43–47

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 38

- ^ Cornelius 2002, pp. 13–14

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 114, quoting a letter from Poe to Neal

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 130

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 5

- ^ Krutch 1926, p. 32

- ^ Cornelius 2002, p. 14

- ^ Meyers 1992, pp. 54–55

- ^ Hecker 2005, pp. 49–51

- ^ Meyers 1992, pp. 50–51

- ^ Hecker 2005, pp. 53–54

- ^ Quinn 1998, pp. 187–188

- ^ Whalen 2001, p. 64

- ^ Jump up to: a b Quinn 1998, p. 305

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 247

- ^ Whalen 2001, p. 74

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 99

- ^ Whalen 2001, p. 82

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 139

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 132

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 162

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 225

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 73

- ^ Jump up to: a b Silverman 1991, p. 124

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 85

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 137

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 113

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 119

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 159

- ^ Sova 2001, pp. 39, 99

- ^ Graham, George; Embury, E.; Peterson, Charles; Stephens, A.; Poe, Edgar (December 1841). "The Closing Year" (PDF). Graham's Magazine. Philadelphia, PA: George R. Graham. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

We began the year almost unknown; certainly far behind our contemporaries in numbers; we close it with a list of twenty-five thousand subscribers, and the assurance on every hand that our popularity has as yet seen only its dawning. (See page 308 of .pdf)

- ^ Quinn 1998, pp. 321–322

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 186

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 144

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 187

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 188

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 179

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sova 2001, p. 34

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 455

- ^ Hoffman 1998, p. 80

- ^ Ostrom 1987, p. 5

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 530

- ^ Schroth, Raymond A. Fordham: A History and Memoir. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008: 22–25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b BronxHistoricalSociety.org 2007

- ^ Weekes 2002, p. 149

- ^ Benton 1987, p. 19

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 628

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 638

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyers 1992, p. 255

- ^ Bramsback 1970, p. 40

- ^ Silverman 1991, pp. 435–436

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 435

- ^ CrimeLibrary.com 2008

- ^ Geiling, Natasha. "The (Still) Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Benitez 1996

- ^ Walsh 2000, pp. 32–33

- ^ Van Luling, Todd (January 19, 2017). "A Vengeful Arch-Nemesis Taught You Fake News About Edgar Allan Poe". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 259 To read Griswold's full obituary, see Edgar Allan Poe obituary at Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoffman 1998, p. 14

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 693

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 101

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 194, quoting Neal

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 263

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 699

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 64

- ^ Jump up to: a b Royot 2002, p. 57

- ^ Kennedy 1987, p. 3

- ^ Koster 2002, p. 336

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ljunquist 2002, p. 15

- ^ Royot 2002, pp. 61–62

- ^ "(Introduction)" (Exhibition at Boston Public Library). The Raven in the Frog Pond: Edgar Allan Poe and the City of Boston. The Trustees of Boston College. March 31, 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Hayes 2002, p. 16

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 169

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 88

- ^ Fisher 1993, pp. 142,149

- ^ Tresch 2002, p. 114

- ^ Whalen 2001, p. 67

- ^ Hungerford 1930, pp. 209–231

- ^ Grayson 2005, pp. 56–77

- ^ Jump up to: a b Krutch 1926, p. 225

- ^ Kagle 1990, p. 104

- ^ Poe 1847, pp. 252–256

- ^ Wilbur 1967, p. 99

- ^ Jannaccone 1974, p. 3

- ^ Hoffman 1998, p. 76

- ^ Krutch 1926, p. 98

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 432

- ^ Zimmerman, Brett (2005). Edgar Allan Poe: Rhetoric and Style. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-7735-2899-4.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (March 6, 2011). "Quoth the detective: Edgar Allan Poe's case against the Boston literati". boston.com. Globe Newspaper Company. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ "Longfellow's Serenity and Poe's Prediction" (Exhibition at Boston Public Library and Massachusetts Historical Society). Forgotten Chapters of Boston's Literary History. The Trustees of Boston College. July 30, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyers 1992, p. 258

- ^ Harner 1990, p. 218

- ^ Frank & Magistrale 1997, p. 103

- ^ Neimeyer 2002, p. 206

- ^ Frank & Magistrale 1997, p. 364

- ^ Frank & Magistrale 1997, p. 372

- ^ McCrum, Robert (November 23, 2013). "The 100 best novels: No 10 – The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket by Edgar Allan Poe (1838)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ "H.P. Lovecraft's Favorite Authors". www.hplovecraft.com. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "Edgar Allan Poe". The Guardian. July 22, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 281

- ^ Carlson 1996, p. 476

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 274

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 265

- ^ New York Times 1894

- ^ Huxley 1967, p. 32

- ^ New York Daily News 2009

- ^ Cappi 1994

- ^ Rombeck 2005

- ^ Harrison 1987

- ^ Smoot & Davidson 1994

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meyers 1992, p. 214

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 399

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 219

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 82

- ^ Jump up to: a b Silverman 1991, p. 152

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, pp. 2, 6

- ^ Friedman 1993, pp. 40–41

- ^ "Though some wondered whether Poe wrote the source text, I find that it previously appeared in the Baltimore Sun of July 4, 1840; and that it was in turn based on a widely reprinted poem (“Nuptial Repartee”) that first appeared in the June 21, 1813, Morning Herald of London. A manuscript in the hand of Hester Thrale (i.e., Hester Lynch Piozzi) in Harvard’s library hints that she may be the true author." From Edgar Allan Poe: The Fever Called Living by Paul Collins. Boston: New Harvest/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014: p. 111.

- ^ Donn, Jeff. "Poe's puzzle decoded, but meaning is mystery". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 15

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 146

- ^ Neimeyer 2002, p. 209

- ^ Gargano 1967, p. 165

- ^ Maslin 2006

- ^ The Raven Society 2014

- ^ Edgar Allan Poe Society 2007

- ^ Burns 2006

- ^ "Poe & Boston: 2009". The Raven Returns: Edgar Allan Poe Bicentennial Celebration. The Trustees of Boston College. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "Edgar Allan Poe Birth Place". Massachusetts Historical Markers on Waymarking.com. Groundspeak, Inc. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ Van Hoy 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b Glenn 2007

- ^ "An Interactive Map of Literary Boston: 1794–1862" (Exhibition). Forgotten Chapters of Boston's Literary History. The Trustees of Boston College. July 30, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ "Edgar Allan Poe Square". The City Record, and Boston News-letter. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ^ "Edgar Allan Poe Square". Massachusetts Historical Markers on Waymarking.com. Groundspeak, Inc. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ Fox, Jeremy C. (February 1, 2013). "Vision for an Edgar Allan Poe memorial in Boston comes closer to reality". boston.com (Boston Globe). Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ Kaiser, Johanna (April 23, 2012). "Boston chooses life-size Edgar Allan Poe statue to commemorate writer's ties to city". boston.com (Boston Globe). Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ "About the project". Edgar Allan Poe Square Public Art Project. Edgar Allan Poe Foundation of Boston, Inc. Archived from the original on April 23, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ Lee, M.G. (October 5, 2014). "Edgar Allan Poe immortalized in the city he loathed". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on July 2, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Lake 2006, p. 195

- ^ Deas, Michael J. (1989). The Portraits and Daguerreotypes of Edgar Allan Poe. University of Virginia. pp. 47–51. ISBN 978-0-8139-1180-9.

- ^ Hall 2007

- ^ Associated Press 2007

- ^ "Poe Toaster tribute is 'nevermore'". The Baltimore Sun. Tribune Company. January 19, 2010. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

Sources

- Allen, Hervey (1927). "Introduction". The Works of Edgar Allan Poe. New York: P.F. Collier & Son. OCLC 1050810755.

- "Man Reveals Legend of Mystery Visitor to Edgar Allan Poe's Grave". Fox News. Associated Press. August 15, 2007. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- Benitez, R, Michael (September 15, 1996). "Poe's Death Is Rewritten as Case of Rabies, Not Telltale Alcohol". New York Times. Based on Benitez, R. M. (1996). "A 39-year-old man with mental status change". Maryland Medical Journal. 45 (9): 765–769. PMID 8810221.

- Benton, Richard P. (1987). "Poe's Literary Labors and Rewards". In Fisher, Benjamin Franklin IV (ed.). Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-0-9616449-1-8.

- Bramsback, Birgit (1970). "The Final Illness and Death of Edgar Allan Poe: An Attempt at Reassessment". Studia Neophilologica. XLII: 40. doi:10.1080/00393277008587456.

- BronxHistoricalSociety.org (2007). "Edgar Allan Poe Cottage". Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- Burns, Niccole (November 15, 2006). "Poe wrote most important works in Philadelphia". School of Communication – University of Miami. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- Cappi, Alberto (1994). "Edgar Allan Poe's Physical Cosmology". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 35: 177–192. Bibcode:1994QJRAS..35..177C.

- Canada, Mark, ed. (1997). "Edgar Allan Poe Chronology". Canada's America. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved June 3, 2007.

- CrimeLibrary.com (2008). "Death Suspicion Cholera". TruTV.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- Carlson, Eric Walter (1996). A Companion to Poe Studies. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-26506-8.

- Cornelius, Kay (2002). "Biography of Edgar Allan Poe". In Harold Bloom (ed.). Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7910-6173-2.

- Edgar Allan Poe Society (2007). "The Baltimore Poe House and Museum". eapoe.org. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- Fisher, Benjamin Franklin IV (1993). "Poe's 'Metzengerstein': Not a Hoax (1971)". On Poe: The Best from American Literature. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 142–149. ISBN 978-0-8223-1311-3.

- Foye, Raymond, ed. (1980). The Unknown Poe (Paperback ed.). San Francisco, CA: City Lights. ISBN 978-0-87286-110-7.

- Frank, Frederick S.; Magistrale, Anthony (1997). The Poe Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-27768-9.

- Friedman, William F. (1993). "Edgar Allan Poe, Cryptographer (1936)". On Poe: The Best from American Literature. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 40–54. ISBN 978-0-8223-1311-3.

- Gargano, James W. (1967). "The Question of Poe's Narrators". In Regan, Robert (ed.). Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-13-684963-6.

- Glenn, Joshua (April 9, 2007). "The house of Poe – mystery solved!". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 8, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- Grayson, Eric (2005). "Weird Science, Weirder Unity: Phrenology and Physiognomy in Edgar Allan Poe". Mode 1: 56–77.

- Hall, Wiley (August 15, 2007). "Poe Fan Takes Credit for Grave Legend". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- Harner, Gary Wayne (1990). "Edgar Allan Poe in France: Baudelaire's Labor of Love". In Fisher, Benjamin Franklin IV (ed.). Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society. ISBN 978-0-9616449-2-5.

- Harrison, Edward (1987). Darkness at Night: A Riddle of the Universe. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-19270-6.

- Harrowitz, Nancy (1984), "The Body of the Detective Model: Charles S. Peirce and Edgar Allan Poe", in Eco, Umberto; Sebeok, Thomas (eds.), The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce, Bloomington, IN: History Workshop, Indiana University Press, pp. 179–197, ISBN 978-0-253-35235-4. Harrowitz discusses Poe's "tales of ratiocination" in the light of Charles Sanders Peirce's logic of making good guesses or abductive reasoning.

- Hayes, Kevin J. (2002). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- Hecker, William J. (2005), Private Perry and Mister Poe: The West Point Poems, Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, ISBN 978-0-8071-3054-4

- Hoffman, Daniel (1998) [1972]. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2321-8.

- Hungerford, Edward (1930). "Poe and Phrenology". American Literature. 1 (3): 209–231. doi:10.2307/2920231. JSTOR 2920231.

- Huxley, Aldous (1967). "Vulgarity in Literature". In Regan, Robert (ed.). Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-13-684963-6.

- Jannaccone, Pasquale (translated by Peter Mitilineos) (1974). "The Aesthetics of Edgar Poe". Poe Studies. 7 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.1974.tb00224.x.

- Kagle, Steven E. (1990). "The Corpse Within Us". In Fisher, Benjamin Franklin IV (ed.). Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society. ISBN 978-0-9616449-2-5.

- Kennedy, J. Gerald (1987). Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03773-9.

- Koster, Donald N. (2002). "Influences of Transcendentalism on American Life and Literature". In Galens, David (ed.). Literary Movements for Students Vol. 1. Detroit: Thompson Gale. ISBN 978-0-7876-6518-0. OCLC 865552323.

- Krutch, Joseph Wood (1926). Edgar Allan Poe: A Study in Genius. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. (1992 reprint: ISBN 978-0-7812-6835-6)

- Lake, Matt (2006). Weird Maryland. New York: Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4027-3906-4.

- Lease, Benjamin (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46969-0.

- Ljunquist, Kent (2002). "The poet as critic". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–20. ISBN 978-0-521-79727-6.

- Maslin, Janet (June 6, 2006). "The Poe Shadow". New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (Paperback ed.). New York: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 978-0-8154-1038-6.

- Neimeyer, Mark (2002). "Poe and Popular Culture". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–224. ISBN 978-0-521-79727-6.

- Nelson, Randy F. (1981). The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, CA: William Kaufmann, Inc. ISBN 978-0-86576-008-0.

- New York Daily News (December 5, 2009). "Edgar Allan Poe's first book from 1827 sells for $662,500; record price for American literature". Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- New York Times (May 20, 1894). "Emerson's Estimate of Poe". The New York Times. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- Ostrom, John Ward (1987). "Poe's Literary Labors and Rewards". In Fisher, Benjamin Franklin IV (ed.). Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society. pp. 37–47. ISBN 978-0-9616449-1-8.

- Poe, Edgar Allan (November 1847). "Tale-Writing – Nathaniel Hawthorne". Godey's Ladies Book: 252–256. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- "Celebrate Edgar Allan Poe's 197th Birthday at the Poe museum". PoeMuseum.org. 2006. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009.

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1998). Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5730-0. (Originally published in 1941 by New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc.)

- The Raven Society (2014). "History". University of Virginia alumni. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- Rombeck, Terry (January 22, 2005). "Poe's little-known science book reprinted". Lawrence Journal-World & News.

- Rosenheim, Shawn James (1997). The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5332-6.

- Royot, Daniel (2002), "Poe's Humor", in Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 57–71, ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1

- Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7230-2.

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance (Paperback ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-092331-0.

- Smoot, George; Davidson, Keay (1994). Wrinkles in Time (Reprint ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-380-72044-6.

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work (Paperback ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0-8160-4161-9.

- Stableford, Brian (2003). "Science fiction before the genre". In James, Edward; Mendlesohn, Farah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–31. ISBN 978-0-521-01657-5.

- Tresch, John (2002). "Extra! Extra! Poe invents science fiction". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–132. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- Van Hoy, David C. (February 18, 2007). "The Fall of the House of Edgar". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- Walsh, John Evangelist (2000) [1968]. Poe the Detective: The Curious Circumstances behind 'The Mystery of Marie Roget'. New York: St. Martins Minotaur. ISBN 978-0-8135-0567-1. (1968 edition printed by Rutgers University Press)

- Weekes, Karen (2002). "Poe's feminine ideal". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 148–162. ISBN 978-0-521-79326-1.

- Whalen, Terance (2001). "Poe and the American Publishing Industry". In Kennedy, J. Gerald (ed.). A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 63–94. ISBN 978-0-19-512150-6.

- Wilbur, Richard (1967). "The House of Poe". In Regan, Robert (ed.). Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-13-684963-6.

Further reading

- Ackroyd, Peter (2008). Poe: A Life Cut Short. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-6988-6.

- Bittner, William (1962). Poe: A Biography. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-09686-7.

- George Washington Eveleth (1922). Thomas Ollive Mabbott (ed.). The letters from George W. Eveleth to Edgar Allan Poe. Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 26 (reprint ed.). The New York Public Library.

- Hutchisson, James M. (2005). Poe. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-721-3.

- Poe, Harry Lee (2008). Edgar Allan Poe: An Illustrated Companion to His Tell-Tale Stories. New York: Metro Books. ISBN 978-1-4351-0469-3.

- Pope-Hennessy, Una (1934). Edgar Allan Poe, 1809–1849: A Critical Biography. New York: Haskell House.

- Robinson, Marilynne, "On Edgar Allan Poe", The New York Review of Books, vol. LXII, no. 2 (February 5, 2015), pp. 4, 6.

- (2021). The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-3742-4785-0.

External links

| Library resources about Edgar Allan Poe |

| By Edgar Allan Poe |

|---|

- Works by Edgar Allan Poe in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Edgar Allan Poe at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Edgar Allan Poe at Internet Archive

- Works by Edgar Allan Poe at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Edgar Allan Poe at Open Library

- Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site

- Edgar Allan Poe Society in Baltimore

- Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia

- Edgar Allan Poe's Personal Correspondence Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Edgar Allan Poe's Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

- 'Funeral' honours Edgar Allan Poe BBC News (with video) 2009-10-11

- Selected Stories from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Edgar Allan Poe at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Edgar Allan Poe at Library of Congress Authorities, with 944 catalog records

- Finding aid to Edgar Allan Poe papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Edgar Allan Poe

- 1809 births

- 1849 deaths

- 19th-century American novelists

- 19th-century American poets

- 19th-century American short story writers

- American detective fiction writers

- American mystery writers

- American horror writers

- American science fiction writers

- American male novelists

- American male short story writers

- American male poets

- Romantic poets

- Novelists from Maryland

- Novelists from Massachusetts

- Novelists from New York (state)

- Novelists from Pennsylvania

- Novelists from Virginia

- Writers of American Southern literature

- Writers of Gothic fiction

- Writers from Baltimore

- Writers from Boston

- Writers from Philadelphia

- Writers from Richmond, Virginia

- Recreational cryptographers

- United States Army soldiers

- United States Military Academy alumni

- University of Virginia alumni

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- People from the Bronx

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- Burials at Westminster Hall and Burying Ground

- Weird fiction writers

- 19th-century pseudonymous writers