Eight Views of Xiaoxiang

| Eight Views of Xiaoxiang | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 瀟湘八景 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 潇湘八景 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang (Chinese: 瀟湘八景; pinyin: Xiāoxiāng Bājǐng) are beautiful scenes of the Xiaoxiang region, in what is now modern Hunan Province, China, that were the subject of the poems and depicted in well-known drawings and paintings from the time of the Song Dynasty. The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang can refer either to various sets of paintings which have been done on this theme, the various verse series on the same theme, or to combinations of both. The Xiaoxiang theme is part of a long poetic and artistic legacy.

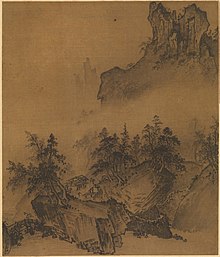

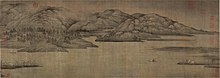

One of the earliest extant artistic depictions of the Xiaoxiang region can be found in the renowned painter Dong Yuan's masterpiece Xiao and Xiang Rivers. The original set of eight painting titles were done by painter, poet, and government official Song Di (c. 1067 – c. 1080), during the reign of Shenzong, in the Song dynasty. A complete version of Song Di's Eight Views of Xiaoxiang has not survived.[1]

After its creation in the 11th century, the "Eight Views" theme became a popular subject for artistry and landscape poetry across the Sinosphere. One Japanese variation, Eight Views of Ōmi, became popular in its own right and was a major subject in ukiyo-e artwork.

The eight scenes[]

- "The rain at night on the Xiaoxiang" (Xiāoxiāng yèyǔ 瀟湘夜雨), in the south (Xiang River area)

- "The wild geese coming home" (Píngshā luòyàn 平沙落雁), in Yongzhou

- "The evening gong at Qingliang Temple" (Yānsì wǎnzhōng 煙寺晚鐘), in Hengyang

- "The temple in the mountain" (Shānshì qínglán 山市晴嵐), in Xiangtan

- "The snow in the evening" (Jiāngtiān mùxuě 江天暮雪), on the Xiang River in Changsha

- "The fishing village in the evening glow" (Yúcūn xīzhào 漁村夕照), in Taoyuan County

- "The moon in autumn on Dongting Lake" (Dòngtíng qiūyuè 洞庭秋月)

- "The sailing ship returning home" (Yuǎnpǔ guīfān 遠浦歸帆), in Xiangyin, in the north (of Hunan)

Symbolism[]

The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang is thematically part of a greater tradition. Generally, it is a theme that as artistically rendered in painting and poetry tends towards the expression of an underlying deep symbolism, such as exile and enlightenment. Furthermore, each scene generally expresses certain, sometimes subtle references. For instance Level Sand: Wild Geese Descend may refer to the historical exile of Qu Yuan in this region and to the poetry which he wrote about it. "Level Sand" may be seen as a reference to Qu Yuan because the Chinese character for level, Píng, was his given name (Yuan was a courtesy name). Furthermore, due to his having drowned himself in one of the often sandy rivers of this region to protest his unjust exile, Qu Yuan was often referred to in poetry as "Embracing Sand", for instance by Li Bo. The wild goose is one of the hallmark symbols of Classical Chinese poetry, with various connotations: the descent of the goose or geese, combined with the descent to the level sand, signifies that the geese are flying south, the season is Autumn, and the forces of Yin are on the rise (thus adding to the involved symbolism).[2]

Influence[]

The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang inspired the people of Far East to create other Eight Views in China, Japan and Korea, as well as series of other numbers of scenes.

In China various versions of The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang have been inspired by the original series, as well as inspiring other series of eight scenes. The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang became a favorite theme of Buddhist monks.

Works covering the Eight Views include a set of paintings by Wang Hong (in the Princeton University Art Museum), now thought to be the earliest surviving depiction of the Eight Views,[3] a set of paintings attributed to Mu Qi (parts in the Kyoto National Museum),[4] and others.

See also[]

- Classical Chinese poetry

- Eight Views

- Eight Views of Jinzhou (Dalian)

- Eight Views of Korea

- Eight Views of Lushun South Road, Dalian

- Eight Views of Omi (近江八景 in Japanese), Japan

- Eight Views of Taiwan

- Geese in Chinese poetry

- List of National Treasures of Japan (paintings)

- Shōnan

- Song dynasty poetry

- Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, series by Hokusai and Hiroshige

- Twelve Views of Bayu

- Xiang River goddesses

- Xiaoxiang

- Xiaoxiang poetry

- Zhu Changfang

References[]

Citations[]

Sources[]

- Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard Univ Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6.

External links[]

- "Eight Views of Xiao and Xiang Rivers" (Images). Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA).

- Chung, Yang-mo; et al. (1998). Smith, Judith G. (ed.). Arts of Korea (pdf). Catalog. Exhibition. Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications. ISBN 9780870998508. OCLC 970040331. Watsonline b12425217.

Contains material on Eight Views of Xiao Xiang

- Chinese paintings