Elamite language

| Elamite | |

|---|---|

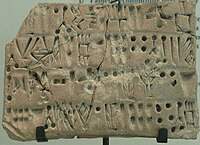

Tablet of Elamite script | |

| Native to | Elamite Empire |

| Region | Western Asia, Iran |

| Era | c. 2800–300 BC |

Early forms | language of Proto-Elamite?

|

| Elamite cuneiform | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | elx |

| ISO 639-3 | elx |

elx | |

| Glottolog | elam1244 |

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was used in present-day southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC.[1] Elamite works disappear from the archeological record after Alexander the Great entered Iran. Elamite is generally thought to have no demonstrable relatives and is usually considered a language isolate. The lack of established relatives makes its interpretation difficult.[2]

A sizeable number of Elamite lexemes are known from the trilingual Behistun inscription and numerous other bilingual or trilingual inscriptions of the Achaemenid Empire, in which Elamite was written using Elamite cuneiform (circa 400 BCE), which is fully deciphered. An important dictionary of the Elamite language, the Elamisches Wörterbuch was published in 1987 by W. Hinz and H. Koch.[3][4] The Linear Elamite script however, one of the scripts used to write the Elamite language circa 2000 BC, has remained elusive until recently.[5]

Writing system[]

Two early scripts of the area remain undeciphered but plausibly have encoded Elamite:

- Proto-Elamite is the oldest known writing system from Iran. It was used during a brief period of time (c. 3100–2900 BC); clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran. It is thought to have developed from early cuneiform (proto-cuneiform) and consists of more than 1,000 signs. It is thought to be largely logographic.

- Linear Elamite is attested in a few monumental inscriptions. It is often claimed that Linear Elamite is a syllabic writing system derived from Proto-Elamite, but it cannot be proven. Linear Elamite was used for a very brief period of time during the last quarter of the third millennium BC.

Later, Elamite cuneiform, adapted from Akkadian cuneiform, was used from c. 2500 to 331 BC. Elamite cuneiform was largely a syllabary of some 130 glyphs at any one time and retained only a few logograms from Akkadian but, over time, the number of logograms increased. The complete corpus of Elamite cuneiform consists of about 20,000 tablets and fragments. The majority belong to the Achaemenid era, and contain primarily economic records.

Linguistic typology[]

Elamite is an agglutinative language,[6] and its grammar was characterized by a well-developed and pervasive nominal class system. Animate nouns have separate markers for first, second and third person, a rather unusual feature. It can be said to display a kind of Suffixaufnahme in that the nominal class markers of the head are also attached to any modifiers, including adjectives, noun adjuncts, possessor nouns and even entire clauses.

History[]

The history of Elamite is periodised as follows:

- Old Elamite (c. 2600–1500 BC)

- Middle Elamite (c. 1500–1000 BC)

- Neo-Elamite (1000–550 BC)

- Achaemenid Elamite (550–330 BC)

Middle Elamite is considered the “classical” period of Elamite, but the best attested variety is Achaemenid Elamite,[7] which was widely used by the Achaemenid Persian state for official inscriptions as well as administrative records and displays significant Old Persian influence. Documents from the Old Elamite and early Neo-Elamite stages are rather scarce.

Neo-Elamite can be regarded as a transition between Middle and Achaemenid Elamite, with respect to language structure.

The Elamite language may have remained in widespread use after the Achaemenid period. Several rulers of Elymais bore the Elamite name Kamnaskires in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. The Acts of the Apostles (c. 80–90 AD) mentions the language as if it was still current. There are no later direct references, but Elamite may be the local language in which, according to the Talmud, the Book of Esther was recited annually to the Jews of Susa in the Sasanian period (224–642 AD). Between the 9th and 13th centuries AD, various Arabic authors refer to a language called Khuzi spoken in Khuzistan, which was not any other language known to those writers. It is possible that it was "a late variant of Elamite".[8]

Phonology[]

Because of the limitations of the language's scripts, its phonology is not well understood.

Its consonants included at least stops /p/, /t/ and /k/, sibilants /s/, /ʃ/ and /z/ (with an uncertain pronunciation), nasals /m/ and /n/, liquids /l/ and /r/ and fricative /h/, which was lost in late Neo-Elamite. Some peculiarities of the spelling have been interpreted as suggesting that there was a contrast between two series of stops (/p/, /t/, /k/ as opposed to /b/, /d/, /g/), but in general, such a distinction was not consistently indicated by written Elamite.

Elamite had at least the vowels /a/, /i/, and /u/ and may also have had /e/, which was not generally expressed unambiguously.

Roots were generally CV, (C)VC, (C)VCV or, more rarely, CVCCV (the first C was usually a nasal).

Morphology[]

Elamite is agglutinative but with fewer morphemes per word than, for example, Sumerian or Hurrian and Urartian and it is mostly suffixing.

Nouns[]

The Elamite nominal system is thoroughly pervaded by a noun class distinction, which combines a gender distinction between animate and inanimate with a personal class distinction, corresponding to the three persons of verbal inflection (first, second, third, plural).

The suffixes are as follows:

Animate:

- 1st person singular: -k

- 2nd person singular: -t

- 3rd person singular: -r or Ø

- 3rd person plural: -p

Inanimate:

- -∅, -me, -n, -t[clarification needed]

The animate third-person suffix -r can serve as a nominalizing suffix and indicate nomen agentis or just members of a class. The inanimate third-person singular suffix -me forms abstracts: sunki-k “a king (first person)” i.e. “I, a king”, sunki-r “a king (third person)”, nap-Ø or nap-ir “a god (third person)”, sunki-p “kings”, nap-ip “gods”, sunki-me “kingdom, kingship”, hal-Ø “town, land”, siya-n “temple”, hala-t “mud brick”.

Modifiers follow their (nominal) heads. In noun phrases and pronoun phrases, the suffixes referring to the head are appended to the modifier, regardless of whether the modifier is another noun (such as a possessor) or an adjective. Sometimes the suffix is preserved on the head as well:

- u šak X-k(i) = “I, the son of X”

- X šak Y-r(i) = “X, the son of Y”

- u sunki-k Hatamti-k = “I, the king of Elam”

- sunki Hatamti-p (or, sometimes, sunki-p Hatamti-p) = “the kings of Elam”

- temti riša-r = “great lord” (lit. “lord great”)

- riša-r nap-ip-ir = “greatest of the gods” (lit. "great of the gods")

- nap-ir u-ri = my god (lit. “god of me”)

- hiya-n nap-ir u-ri-me = the throne hall of my god

- takki-me puhu nika-me-me = “the life of our children”

- sunki-p uri-p u-p(e) = ”kings, my predecessors” (lit. “kings, predecessors of me”)

This system, in which the noun class suffixes function as derivational morphemes as well as agreement markers and indirectly as subordinating morphemes, is best seen in Middle Elamite. It was, to a great extent, broken down in Achaemenid Elamite, where possession and, sometimes, attributive relationships are uniformly expressed with the “genitive case” suffix -na appended to the modifier: e.g. šak X-na “son of X”. The suffix -na, which probably originated from the inanimate agreement suffix -n followed by the nominalizing particle -a (see below), appeared already in Neo-Elamite.

The personal pronouns distinguish nominative and accusative case forms. They are as follows:

| Case | 1st sg. | 2nd sg. | 3rd sg. | 1st pl. | 2nd pl. | 3rd pl. | Inanimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | u | ni/nu | i/hi | nika/nuku | num/numi | ap/appi | i/in |

| Accusative | un | nun | ir/in | nukun | numun | appin | i/in |

In general, no special possessive pronouns are needed in view of the construction with the noun class suffixes. Nevertheless, a set of separate third-person animate possessives -e (sing.) / appi-e (plur.) is occasionally used already in Middle Elamite: puhu-e “her children”, hiš-api-e “their name”. The relative pronouns are akka “who” and appa “what, which”.

Verbs[]