Eleanor Rigby

| "Eleanor Rigby" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

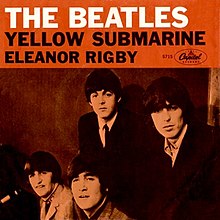

US picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Beatles | ||||

| from the album Revolver | ||||

| A-side | "Yellow Submarine" (double A-side) | |||

| Released | 5 August 1966 | |||

| Recorded | 28–29 April & 6 June 1966 | |||

| Studio | EMI, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:08 | |||

| Label | Parlophone (UK), Capitol (US) | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||

| Producer(s) | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Eleanor Rigby" on YouTube | ||||

"Eleanor Rigby" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1966 album Revolver. It was also issued on a double A-side single, paired with "Yellow Submarine". The song was written primarily by Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon–McCartney.[3]

The song continued the transformation of the Beatles from a mainly rock and roll- and pop-oriented act to a more experimental, studio-based band. With a double string quartet arrangement by George Martin and lyrics providing a narrative on loneliness, "Eleanor Rigby" broke sharply with popular music conventions, both musically and lyrically.[4] Richie Unterberger of AllMusic cites the band's "singing about the neglected concerns and fates of the elderly" on the song as "just one example of why the Beatles' appeal reached so far beyond the traditional rock audience".[5]

Composition[]

"Eleanor Rigby" has often been described as a lament for lonely people[6] or a commentary on post-war life in Britain.[7][8] Paul McCartney came up with the melody as he experimented on his piano. The singer-composer Donovan reported that he heard McCartney play it to him before it was finished, with completely different lyrics.[9] The original name of the protagonist that he initially chose was not Eleanor Rigby, but Miss Daisy Hawkins.[10] In 1966, McCartney recalled how he got the idea for his song:

I was sitting at the piano when I thought of it. The first few bars just came to me, and I got this name in my head ... "Daisy Hawkins picks up the rice in the church". I don't know why. I couldn't think of much more so I put it away for a day. Then the name "Father McCartney" came to me, and all the lonely people. But I thought that people would think it was supposed to be about my Dad sitting knitting his socks. Dad's a happy lad. So I went through the telephone book and I got the name "McKenzie".[11]

Others have posited that "Father McKenzie" refers to "Father" Tommy McKenzie, who was the compere at Northwich Memorial Hall.[12][13]

McCartney said he came up with the name "Eleanor" from actress Eleanor Bron, who had starred with the Beatles in the film Help!. "Rigby" came from the name of a store in Bristol,[14] "Rigby & Evens Ltd, Wine & Spirit Shippers", which he noticed while seeing his girlfriend of the time, Jane Asher, act in The Happiest Days of Your Life.[15] He recalled in 1984, "I just liked the name. I was looking for a name that sounded natural. 'Eleanor Rigby' sounded natural."[citation needed]

McCartney wrote the first verse by himself, and the Beatles finished the song in the music room of John Lennon's home at Kenwood. John Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr and Lennon's childhood friend Pete Shotton all listened to McCartney play his song through and contributed ideas. Harrison came up with the "Ah, look at all the lonely people" hook. Starr contributed the line "writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear" and suggested making "Father McCartney" darn his socks, which McCartney liked. It was then that Shotton suggested that McCartney change the name of the priest, in case listeners mistook the fictional character in the song for McCartney's own father.[16]

McCartney could not decide how to end the song, and Shotton finally suggested that the two lonely people come together too late as Father McKenzie conducts Eleanor Rigby's funeral. At the time, Lennon rejected the idea out of hand, but McCartney said nothing and used the idea to finish off the song, later acknowledging Shotton's help.[16]

Lennon was quoted in 1971 as having said that he "wrote a good half of the lyrics or more"[17] and in 1980 claimed that he wrote all but the first verse,[18] but Shotton remembered Lennon's contribution as being "absolutely nil".[19] McCartney said that "John helped me on a few words but I'd put it down 80–20 to me, something like that."[20] Historiographer Erin Torkelson Weber has studied all available historical treatments of the issue and has concluded that McCartney was the principal author of the song, while speculating that Lennon's assertions to the contrary were the result of lingering unresolved anger and the influence of manager Allen Klein.[21]

Recording[]

"Eleanor Rigby" does not have a standard pop backing. None of the Beatles played instruments on it, though Lennon and Harrison did contribute harmony vocals.[22] Like the earlier song "Yesterday", "Eleanor Rigby" employs a classical string ensemble—in this case an octet of studio musicians, comprising four violins, two violas, and two cellos, all performing a score composed by producer George Martin.[22] Whereas "Yesterday" is played legato, "Eleanor Rigby" is played mainly in staccato chords with melodic embellishments. McCartney, reluctant to repeat what he had done on "Yesterday", explicitly expressed that he did not want the strings to sound too cloying. For the most part, the instruments "double up"—that is, they serve as a single string quartet but with two instruments playing each of the four parts. Microphones were placed close to the instruments to produce a more biting and raw sound. Engineer Geoff Emerick was admonished by the string players saying "You're not supposed to do that." Fearing such close proximity to their instruments would expose the slightest deficiencies in their technique, the players kept moving their chairs away from the microphones until Martin got on the talk-back system and scolded: "Stop moving the chairs!" Martin recorded two versions, one with vibrato and one without, the latter of which was used. Lennon recalled in 1980 that "Eleanor Rigby" was "Paul's baby, and I helped with the education of the child ... The violin backing was Paul's idea. Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi, and it was very good."[23] The octet was recorded on 28 April 1966, in Studio 2 at Abbey Road Studios; it was completed in Studio 3 on 29 April and on 6 June. Take 15 was selected as the master.[24]

In his autobiography All You Need Is Ears, Martin takes credit for combining two of the vocal parts—"Ah! look at all the lonely people" and "All the lonely people"—having noticed that they would work together contrapuntally. He cited the influence of Bernard Herrmann's work on his string scoring. (Originally he cited the score for the film Fahrenheit 451,[25] but this was a mistake as the film was not released until several months after the recording.) Martin stated he was thinking of Herrmann's score for Psycho.[26]

The original stereo mix had McCartney's voice only in the right channel during the verses, with the string octet mixed to one channel, while the mono single and mono LP featured a more balanced mix. On the Yellow Submarine Songtrack, Love and the 2015 remix of 1, McCartney's voice is centred and the string octet appears in stereo, creating a modern-sounding mix.

Harmony[]

The song is a prominent example of mode mixture, specifically between the Aeolian mode, also known as natural minor, and the Dorian mode. Set in E minor, the song is based on the chord progression Em–C, typical of the Aeolian mode and utilising notes ♭3, ♭6, and ♭7 in this scale. The verse melody is written in Dorian mode, a minor scale with the natural sixth degree.[27] "Eleanor Rigby" opens with a C-major vocal harmony ("Aah, look at all ..."), before shifting to E-minor (on "lonely people"). The Aeolian C-natural note returns later in the verse on the word "dre-eam" (C–B) as the C chord resolves to the tonic Em, giving an urgency to the melody's mood.

The Dorian mode appears with the C# note (6 in the Em scale) at the beginning of the phrase "in the church". The chorus beginning "All the lonely people" involves the viola in a chromatic descent to the 5th; from 7 (D natural on "All the lonely peo-") to 6 (C♯ on "-ple") to ♭6 (C on "they) to 5 (B on "from"). This is said to "add an air of inevitability to the flow of the music (and perhaps to the plight of the characters in the song)".[28]

Real people named Eleanor Rigby[]

In the 1980s, the grave of an Eleanor Rigby was "discovered" in the graveyard of St Peter's Parish Church in Woolton, Liverpool, and a few yards (a few metres) away from that, another tombstone with the last name "McKenzie" scrawled across it.[29][30] During their teenage years, McCartney and Lennon spent time sunbathing there, within earshot of where the two had first met during a fete in 1957.

Years later,[when?] McCartney said that the coincidence could be a product of his subconscious (cryptomnesia).[29] In 2008, however, when a birth certificate was sold at auction of a woman named Eleanor Rigby, McCartney restated publicly: "Eleanor Rigby is a totally fictitious character that I made up ... If someone wants to spend money buying a document to prove a fictitious character exists, that's fine with me."[31]

An actual Eleanor Rigby was born on 29 August 1895 and lived in Liverpool, possibly in the suburb of Woolton, where she married a man named Thomas Woods on Boxing Day (December 26th), 1930. She died on 10 October 1939 of a brain haemorrhage at the age of 44 and was buried three days later. Her tombstone has become a landmark to Beatles fans visiting Liverpool. A digitised version was added to the 1995 music video for the Beatles' reunion song "Free as a Bird".

In June 1990, McCartney donated to Sunbeams Music Trust[32] a document dating from 1911 which had been signed by the 16-year-old Eleanor Rigby; this instantly attracted significant international interest from collectors because of the coincidental significance and provenance of the document.[33] The nearly 100-year-old document was sold at auction in November 2008 for £115,000.[34]

Releases[]

Simultaneously released on 5 August 1966 on both the album Revolver and on a double A-side single with "Yellow Submarine",[35] "Eleanor Rigby" spent four weeks at number one on the British charts.[22] In the United States, where each side of a single was eligible to chart, the song peaked at number 11 and "Yellow Submarine" reached number 2.[36]

"Eleanor Rigby" was nominated for three Grammy Awards and won the 1966 Grammy for Best Contemporary (R&R) Vocal Performance, Male or Female for McCartney. Thirty years later, a stereo remix of Martin's isolated string arrangement was released on the Beatles' Anthology 2. A decade after that, a remixed version of the track was included on the 2006 album Love.

It is the second song to appear in the Beatles' 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine. The first is "Yellow Submarine"; it and "Eleanor Rigby" are the only songs in the film which the animated Beatles are not seen to be singing. "Eleanor Rigby" is introduced just before the Liverpool sequence of the film; its poignancy ties in quite well with Ringo Starr (the first member of the group to encounter the submarine), who is represented as quietly bored and depressed. "Compared with my life, Eleanor Rigby's was a gay, mad world."

In 1984, a re-interpretation of the song was included in the film and album Give My Regards to Broad Street, written by and starring McCartney. It segues into a symphonic extension, "Eleanor's Dream".

A fully remixed stereo version of the original "Eleanor Rigby" song was issued in 1999 on the Yellow Submarine Songtrack. Further new mixes were released on Love and the 2015 version of 1.

Legacy[]

"Eleanor Rigby" was important in the Beatles' evolution from a pop, live-performance band to a more experimental, studio-oriented band. In a 1967 interview, Pete Townshend of the Who commented: "I think 'Eleanor Rigby' was a very important musical move forward. It certainly inspired me to write and listen to things in that vein."[37]

Although "Eleanor Rigby" was far from the first pop song to deal with death and loneliness, according to Ian MacDonald it "came as quite a shock to pop listeners in 1966".[22] It took a bleak message of depression and desolation, written by a famous pop band, with a sombre, almost funeral-like backing, to the number one spot of the pop charts.[22] The bleak lyrics were not the Beatles' first deviation from love songs, but were some of the most explicit.

In some reference books on classical music, "Eleanor Rigby" is included and considered comparable to art songs (lieder). Classical and theatrical composer Howard Goodall said that the Beatles' works are "a stunning roll-call of sublime melodies that perhaps only Mozart can match in European musical history" and that they "almost single-handedly rescued the Western musical system" from the "plague years of the avant-garde". About "Eleanor Rigby", he said it is "an urban version of a tragic ballad in the Dorian mode".[38]

American songwriter Jerry Leiber once said: "The Beatles are second to none in all departments. I don't think there has ever been a better song written than 'Eleanor Rigby'."[39] Ray Davies of the Kinks offered a contrary view in July 1966 when invited to give a song-by-song rundown of Revolver in the music paper Disc and Music Echo. He dismissed "Eleanor Rigby" as a song designed "to please music teachers in primary schools",[40] adding that "I can imagine John saying, 'I'm going to write this for my old schoolmistress.' Still it's very commercial."[41]

Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees said that their 1969 song "Melody Fair" was influenced by "Eleanor Rigby".[42] America's single "Lonely People" was written by Dan Peek in 1973 as an optimistic response to "Eleanor Rigby".

The song is ranked at number 138 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list. [43]

Personnel[]

According to Ian MacDonald:[22]

The Beatles

- Paul McCartney – lead and harmony vocals

- John Lennon – harmony vocal

- George Harrison – harmony vocal

Additional musicians

- Tony Gilbert – violin

- Sidney Sax – violin

- John Sharpe – violin

- Juergen Hess – violin

- Stephen Shingles – viola

- John Underwood – viola

- Derek Simpson – cello

- Stephen Lansberry – cello

- George Martin – producer, string arrangement

Charts[]

| Chart (1966) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Canadian CHUM Chart | 1 |

| New Zealand (Listener)[44] | 1 |

| UK Singles Chart[45] | 1 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[46] | 11 |

| Chart (1986) | Peak position |

| UK Singles Chart | 63 |

Charting renditions[]

- Ray Charles recorded a version that was released as a single in both the U.S. and the U.K. in 1968. Charles's version entered the U.S. Cash Box chart on 15 June 1968,[47] peaking at No.39 during the weeks of 13 July 1968 & 20 July 1968, and entered the U.K. singles chart on 31 July 1968,[48] peaking at No.36 (week of 7 August 1968) during a 9-week chart run.[citation needed]

- Aretha Franklin's cover charted at number 17 on the US singles chart on 13 December 1969.[49] Beatles scholar Chris Ingham says both Charles and Franklin's versions were notable progressive soul interpretations of the song.[50]

Notes[]

- ^ Stanley, Bob (20 September 2007). "Pop: Baroque and a soft place". The Guardian. London. Film & music section, p. 8. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 138.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 281.

- ^ Campbell, Michael; Brody, James (2008). Rock and Roll: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-534-64295-2.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'Eleanor Rigby'". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Time 2010.

- ^ Harris 2004.

- ^ Dewhurst 1970.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 282.

- ^ The Beatles interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- ^ Beatles Interview Database 2007.

- ^ Northwich Guardian 2000.

- ^ RR Auction 2007.

- ^ Paul McCartney Breaks Down His Most Iconic Songs | GQ. 11 September 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ University of Bristol

- ^ Jump up to: a b Turner 1994, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 283.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 284.

- ^ Miles 1997.

- ^ Weber, Erin Torkelson. "Lennon vs. McCartney: How Beatles History was Written and Re-Written". youtube. Newman University History Department. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f MacDonald 2005, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Lewisohn 1988, pp. 77, 82.

- ^ Pollack 1994.

- ^ Ryan & Kehew 2006.

- ^ Dominic Pedler. The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. Music Sales Limited. Omnibus Press. NY. 2003. p. 276.

- ^ Dominic Pedler. The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. Music Sales Limited. Omnibus Press. NY. 2003. pp 333–334

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Beatles 2000, p. 208.

- ^ Hill 2007.

- ^ BBC News

- ^ Sunbeams Trust 2008.

- ^ Collett-White 2008.

- ^ Meeja 2008.

- ^ Lewisohn 1988, p. 200.

- ^ Wallgren 1982, p. 48.

- ^ Wilkerson 2006.

- ^ Goodall 2010.

- ^ Swainson 2000, p. 555.

- ^ Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York, NY: Ecco. pp. 260–61. ISBN 978-0-06-247558-9.

- ^ Staff writer (30 July 1966). "Ray Davies Reviews the Beatles LP". Disc and Music Echo. p. 16.

- ^ Hughes, Andrew (2009). The Bee Gees: Tales of the Brothers Gibb. ISBN 9780857120045. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Eleanor Rigby ranked 138th greatest song". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ 14 October 1966

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 50: 18 August 1966 through 24 August 1966". The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles Eleanor Rigby Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 singles, week ending 15 June 1968". Randy Price. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 50: 31 July 1968 through 6 August 1968". The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Corpuz, Kristin (25 March 2017). "Happy Birthday, Aretha Franklin! Looking Back at the Queen of Soul's Top 40 Biggest Hot 100 Hits". Billboard. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Ingham, Chris (2003). The Rough Guide to the Beatles. Rough Guides. p. 242. ISBN 1843531402.

References[]

- "Beatles' Tribute to 'Father McKenzie'". Northwich Guardian. 2000. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- "Bel Canto & the Beatles". Time. 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Collett-White, Mike (11 November 2008). "Document with clues to Beatles enigma up for sale". Yahoo News.[permanent dead link]

- Dewhurst, Keith (15 April 1970). "The day of the Beatles". guardian.co.uk. London.

- "Eleanor Rigby clues go for a song". Meeja. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- Goodall, Howard (2010). "Howard Goodall's 20th Century Greats". Archived from the original on 2 June 2007.

- Harris, John (20 June 2004). "Revolver, The Beatles". The Observer. London.

- Hill, Roger (2007). "Gravestone of an "Eleanor Rigby" in the graveyard of St. Peter's Parish Church in Woolton, Liverpool". Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- "Item 934 - Beatles: Father McKenzie". RR Auction. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- Ryan, Kevin; Kehew, Brian (2006). Recording the Beatles. Houston, TX.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1988). The Beatles Recording Sessions. New York. ISBN 0-517-57066-1.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Second Revised ed.). London. ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. New York. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Pollack, Alan W. (13 February 1994). "Notes on "Eleanor Rigby"". Notes on ... Series.

- "Revolver: Eleanor Rigby". Beatles Interview Database. 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock 'n' Roll. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-009-0.

- "The Rolling Stone 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 August 2006. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- Sheff, David (2000). All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York. ISBN 0-312-25464-4.

- "Sunbeams dinner and auction". Sunbeams Trust. November 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- Swainson, Bill (2000). Encarta Book of Quotations. ISBN 0-312-23000-1.

- Turner, Steve (2010). A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song. New York. ISBN 978-0-06-084409-7.

- Wallgren, Mark (1982). The Beatles on Record. New York. ISBN 0-671-45682-2.

- Wilkerson, Mark (2006). Amazing Journey: The Life of Pete Townshend. ISBN 1-4116-7700-5.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Revolver (Beatles album) |

- Art rock songs

- The Beatles songs

- Baroque pop songs

- 1966 singles

- 1966 songs

- 1960s ballads

- Pop ballads

- UK Singles Chart number-one singles

- Number-one singles in Germany

- Number-one singles in New Zealand

- Number-one singles in Norway

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Aretha Franklin songs

- Parlophone singles

- Song recordings produced by George Martin

- Songs written by Lennon–McCartney

- Joan Baez songs

- Ray Charles songs

- Tony Bennett songs

- Songs published by Northern Songs

- RPM Top Singles number-one singles

- Capitol Records singles

- Songs about fictional female characters

- Songs about poverty

- Songs about loneliness

- Songs about death

- Rock ballads

- Songs composed in E minor