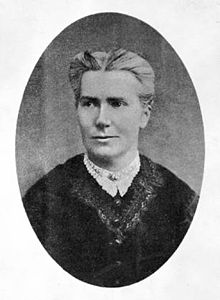

Emily Blackwell

Emily Blackwell, M.D. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 8, 1826 Bristol, England |

| Died | September 7, 1910 (aged 83) |

| Education | Western Reserve |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Physician |

Emily Blackwell (October 8, 1826 – September 7, 1910) was the second woman to earn a medical degree at what is now Case Western Reserve University, and the third woman (after her sister Elizabeth Blackwell and Lydia Folger Fowler) to earn a medical degree in the United States.[1] In 1993, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[2]

Biography[]

Blackwell was born on October 8, 1826, in Bristol, England. In 1832 the family emigrated to the US and in 1837 settled near Cincinnati, Ohio. Inspired by the example of her older sister, Elizabeth, she applied to study medicine in Geneva, New York, where her sister graduated in 1849 but was rejected. She was then accepted to Rush Medical College for a year, but the state medical society censured the college and she was only able to attend one semester. Eventually, she was accepted to the Medical College of Cleveland, Ohio, Medical Branch of Western Reserve University, earning her degree in 1854.[3] In 1857 the Blackwell sisters and Marie Zakrzewska established the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. From the beginning, Emily took responsibility for management of the infirmary and in large part for the raising of funds. For the next forty years, she managed the infirmary, overseeing surgery, nursing, and bookkeeping. Blackwell traveled to Albany to convince the legislature to provide the hospital with funds that would ensure long-term financial stability. She transformed an institution housed in a rented 16-room house into a full-fledged hospital. By 1874 the infirmary was serving over 7,000 patients annually.

During the American Civil War, Blackwell helped organize the Women's Central Association of Relief, which selected and trained nurses for service in the war. Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell and Mary Livermore also played an important role in the development of the United States Sanitary Commission.

After the war, in 1868 the Blackwell sisters established the Women's Medical College in New York City. Emily became professor of obstetrics and in 1869, when Elizabeth moved to London to help form the London School of Medicine for Women, became dean of the college. In 1876 it became a three-year institution, and in 1893 it became a four-year college, ahead of much of the profession. By 1899 the college had trained 364 women doctors.

From 1883, Blackwell lived with her partner Elizabeth Cushier, who also served as a doctor at the infirmary.[4] Blackwell and Cushier retired at the turn of the century. After traveling abroad for a year and a half, they spent the next winters at their home in Montclair, New Jersey, and summers in Maine.[5] Blackwell died on September 7, 1910, in York Cliffs, Maine, a few months after her sister Elizabeth's death in England.[6]

Legacy[]

Blackwell was denied admission to study medicine at the Geneva Medical College in Geneva, New York, from which her older sister had graduated. After being rejected by several other schools, she was finally accepted in 1853 by Rush Medical College in Chicago. However, in 1853, when male students complained about having to study with a woman, the Illinois Medical Society vetoed her admission. She was accepted by the Western Reserve University (now Case Western Reserve University) in Cleveland, Ohio, and earned her M.D. degree in 1854. She subsequently pursued further studies in Edinburgh under Sir James Young Simpson, in London under Dr. William Jenner, and in Paris, Berlin, and Dresden.

At Western Reserve University, the medical education of women began at the urging of reform-minded Dean John Delamater, who was backed by the Ohio Female Medical Education Society, formed in 1852 to provide moral and financial support for the women medical students. Despite their efforts, the Western Reserve faculty voted to put an end to Delamater's policies in 1856, finding it "inexpedient" to continue admitting women. (The American Medical Association also adopted a report in 1856 advising against coeducation in medicine.) Western Reserve resumed admitting women in 1879, but did so only sporadically for five years. Admission of women at Western Reserve recommenced on a continuous basis in 1918.

References[]

- ^ "Dr. Emily Blackwell." Retrieved: October 23, 2013.

- ^ National Women's Hall of Fame, Emily Blackwell

- ^ Kelly, Howard A.; Burrage, Walter L. (eds.). . . Baltimore: The Norman, Remington Company.

- ^ Faderman, Lillian (2000). To Believe in Women. Mariner Books. pp. 6, 289–290. ISBN 978-0-618-05697-2.

- ^ Faderman (2000), p. 289

- ^ "Dr. Emily Blackwell Dead" (PDF). The New York Times. September 9, 1910. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

One of Founders of First Women's Hospital In America.

Further reading[]

- Webster's Dictionary of American Women, ISBN 0-7651-9793-6.

- Blackwell, Emily. "Blackwell, Emily". American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Loue, edited by Sana; Sajatovic, edited by Martha; Cain, Tambra (2004). "Blackwell, Elizabeth". Encyclopedia of woment's health. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. ISBN 978-0306480737.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Atwater, Edward C (2016). Women Medical Doctors in the United States before the Civil War: A Biographical Dictionary. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 9781580465717. OCLC 945359277.

- Nimura, Janice P. (2021). The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women and Women to Medicine. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393635546.

External links[]

- Changing the Face of Medicine — at NIH

- The Emily Blackwell Society — at Case Western

- Papers, 1832–1981. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Emily Blackwell at Find a Grave

- 1826 births

- 1910 deaths

- People from Bristol

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- American feminists

- American hospital administrators

- American obstetricians

- Blackwell family

- Case Western Reserve University alumni

- English women medical doctors

- History of women's rights in the United States

- United States Sanitary Commission people

- Women in the American Civil War

- 19th-century American women physicians

- 19th-century American physicians

- LGBT physicians

- LGBT people from the United States

- 19th-century English women

- 19th-century English people